Nehemiah 8:1-10

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Moving Forward As a People of Christ Nehemiah 8 Introduction

Moving Forward as a People of Christ Nehemiah 8 Introduction For about a month now, I have had some things stirring in my heart and I have just let them percolate there until the right time for them to be poured out. I needed them to really get settled in me before they were spoken. Actually they are not new words I have communicated, but freshly experienced and seen. It is was not until my trip overseas until I felt like it was time to share them and these things will be the focus of our time today. I shared these with the leadership group overseas. We will finish Revelation 20 next week and then onto the rest of the book. These thoughts have been developing over time and have primarily come from my experience and perspective with our Christian life in the Western world. When you look at the church in the West, in which we are a part of, there are two clear and distinctive things that are impacting church life now and will so even more in the years to come. These two great challenges we are facing in regard to influence and shaping are important to understand so we can aware and prepared for what is definitely coming on stronger and stronger in the western world. So, I would like to begin our time by way of introducing these two critical barriers in regard to the church moving forward as the people of Christ. There is an external challenge and an internal one that we must come to grips with. -

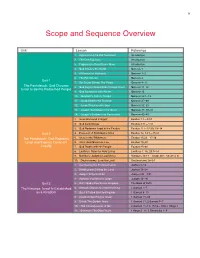

Scope and Sequence Overview

9 Scope and Sequence Overview Unit Lesson Reference 1. Approaching the Old Testament Introduction 2. The One Big Story Introduction 3. Preparing to Read God's Word Introduction 4. God Creates the World Genesis 1 5. A Mission for Humanity Genesis 1–2 6. The Fall into Sin Genesis 3 Unit 1 7. Sin Grows Worse: The Flood Genesis 4–11 The Pentateuch: God Chooses 8. God Begins Redemption through Israel Genesis 11–12 Israel to Be His Redeemed People 9. God Covenants with Abram Genesis 15 10. Abraham's Faith Is Tested Genesis 22:1–19 11. Jacob Inherits the Promise Genesis 27–28 12. Jacob Wrestles with God Genesis 32–33 13. Joseph: God Meant It for Good Genesis 37; 39–41 14. Joseph's Brothers Are Reconciled Genesis 42–45 1. Israel Enslaved in Egypt Exodus 1:1—2:10 2. God Calls Moses Exodus 2:11—4:31 3. God Redeems Israel in the Exodus Exodus 11:1–12:39; 13–14 Unit 2 4. Passover: A Redemption Meal Exodus 12; 14:1—15:21 The Pentateuch: God Redeems 5. Israel in the Wilderness Exodus 15:22—17:16 Israel and Expects Covenant 6. Sinai: God Gives His Law Exodus 19–20 Loyalty 7. God Dwells with His People Exodus 25–40 8. Leviticus: Rules for Holy Living Leviticus 1; 16; 23:9–14 9. Numbers: Judgment and Mercy Numbers 13:17—14:45; 20:1–13; 21:4–8 10. Deuteronomy: Love the Lord! Deuteronomy 28–34 1. Conquering the Promised Land Joshua 1–12 2. -

Week Thirty-Eight: a Kingdom Rebuilt

Week Thirty-eight: A Kingdom Rebuilt - Nehemiah 8-9 Overview As he prepares Israel to enter the land of promise, Moses speaks about the importance of Bible literacy: “At the end of every seven years, at the appointed time . you shall read this law before all Israel in their hearing . that their children, who have not known it, may hear and learn to fear the LORD your God as long as you live in the land” (Deut. 31:9-13). He completes the writing of the words of the law in a book and commands that the book be placed prominently beside the ark of the covenant (31:24-26). He regards Bible literacy as the very heart of Israel, “For it is not a futile thing for you, because it is your life, and by this word you shall prolong your days in the land which you cross over the Jordan to possess” (32:47). Moses also speaks about the time that their disobedience will take them into captivity, but that the LORD will bring them back to the land of promise—“that the LORD your God will bring you back from captivity, and have compassion on you, and gather you again from all the nations where the LORD your God has scattered you . from there the LORD your God will gather you, and from there He will bring you” (Deut. 30:3-4). Throughout Israel’s history they ignore Moses’ urgent warning regarding Bible literacy. Nearly 1,000 years pass, and they are taken captive by the Babylonians. -

The Ironic Death of Josiah in 2 Chronicles

3mitchell.qxd 5/1/2006 9:29 AM Page 421 The Ironic Death of Josiah in 2 Chronicles CHRISTINE MITCHELL St. Andrew’s College Saskatoon, SK S7N 0W3, Canada MOST RECENT STUDIES OF 2 Chronicles 34–35 have attempted to deal with various historical issues of the text.1 Although many of the insights from these studies are valuable, very little attention has been paid to reading Josiah’s rule and death in 2 Chronicles from a literary perspective.2 In this contribution, there- fore, I propose a literary reading of 2 Chronicles 34–35 on the terms of the Chron- I would like to thank Gary Knoppers and Ehud Ben Zvi for their comments on this article as it evolved. Any errors that remain are, of course, my own. 1 The discussion began with H. G. M. Williamson, “The Death of Josiah and the Continuing Development of the Deuteronomic History,” VT 32 (1982) 242-48, and continued with C. T. Begg, “The Death of Josiah: Another View,” VT 37 (1987) 1-8; H. G. M. Williamson, “Reliving the Death of Josiah: A Reply to C. T. Begg,” VT 37 (1987) 9-15; Zipora Talshir, “The Three Deaths of Josiah and the Strata of Biblical Historiography (2 Kings xxiii 29-30; 2 Chronicles xxxv 20-5; 1 Esdras i 23-31),” VT 46 (1996) 213-36; Baruch Halpern, “Why Manasseh Is Blamed for the Babylonian Exile: The Evolution of a Biblical Tradition,” VT 48 (1998) 473-514. The work in these articles is often in conversation with that of C. -

Table of Contents

Table of ConTenTs How Scripture Came to Us Lesson 1 Scribes and Scriptures ����������������������������������������������������� 3 Jeremiah 36:4-8, 20-26, 32; Luke 1:1-4 Lesson 2 Scholars and Translators ������������������������������������������������� 8 Nehemiah 8:1, 5-8; Acts 8:26-31 Lesson 3 Misapplying Scripture �����������������������������������������������������13 2 Timothy 2:14-18, 22-26; 2 Peter 3:15-16 Lesson 4 Reading with Understanding �������������������������������������������18 Matthew 22:34-40; Acts 17:10-12 WhaT’s in Your TeaChing guide This Teaching Guide has three purposes: ‰ to give the teacher tools for focusing on the content of the session in the Study Guide. ‰ to give the teacher additional Bible background information. ‰ to give the teacher variety and choice in preparation. The Teaching Guide includes two major components: Teacher Helps and Teacher Options. Teacher Helps Bible Background The Study Guide is your main Teaching Outline source of Bible study material. provides you with an outline This section helps you more fully of the main themes in the understand and Study Guide. interpret the Scripture text. Teacher Options The next three sections provide a beginning, middle, and end for the session, with focus paragraphs in between. Focus Paragraphs are printed in italics at the top of the page because they are the most important part of the Teaching Guide. These paragraphs will help you move your class from “what the text meant” to “what the text means.” You Can Choose! There is more material in each session than you can use, so choose the options from each section to tailor the session to the needs of your group. -

Paragraphs of the Bible: Nehemiah 8-13

Scholars Crossing A One-Line Introduction to the Paragraphs of the Bible A Guide to the Systematic Study of the Bible 6-2018 Paragraphs of the Bible: Nehemiah 8-13 Harold Willmington Liberty University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/intro_paragraphs_bible Part of the Biblical Studies Commons, Christianity Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Willmington, Harold, "Paragraphs of the Bible: Nehemiah 8-13" (2018). A One-Line Introduction to the Paragraphs of the Bible. 65. https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/intro_paragraphs_bible/65 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the A Guide to the Systematic Study of the Bible at Scholars Crossing. It has been accepted for inclusion in A One-Line Introduction to the Paragraphs of the Bible by an authorized administrator of Scholars Crossing. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ARTICLE FORTY-EIGHT PARAGRAPHS OF THE BIBLE – NEHEMIAH 8-13 EIGHT A. Read and explained by the Water Gate (8:1-8) B. A day to be glad, not sad (8:9-12) C. Home sweet home for seven days! (8:13-18) NINE A. One fourth of the day reading; one fourth repenting and rejoicing (9:1-5) B. The prayer of the eight: From Abraham through the Exodus (9:6-21) C. The prayer of the eight: From the Conquest to the Return (9:22-31) D. The prayer of the eight: Our present situation (9:32-37) E. “Let’s make a deal!” (9:38) TEN A. -

Ezra Nehemiah

VOLUME 11 OLD TESTAMENT NEW COLLEGEVILLE THE BIBLE COMMENTARY EZRA NEHEMIAH Thomas M. Bolin SERIES EDITOR Daniel Durken, O.S.B. LITURGICAL PRESS Collegeville, Minnesota www.litpress.org Nihil Obstat: Reverend Robert C. Harren, J.C.L. Imprimatur: W Most Reverend John F. Kinney, J.C.D., D.D., Bishop of Saint Cloud, Minnesota, December 12, 2011. Design by Ann Blattner. Cover illustration: Square Before the Watergate by Hazel Dolby. Copyright 2010 The Saint John’s Bible, Order of Saint Benedict, Collegeville, Minnesota USA. Used by permission. All rights reserved. Photos: pages 20, 24, Wikimedia Commons; page 80, Thinkstock.com. Maps on pages 110 and 111 created by Robert Cronan of Lucidity Design, LLC. Scripture texts used in this work are taken from the New American Bible, revised edi- tion © 2010, 1991, 1986, 1970 Confraternity of Christian Doctrine, Inc., Washington, DC. All Rights Reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the copyright owner. © 2012 by Order of Saint Benedict, Collegeville, Minnesota. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, by print, microfilm, micro fiche, mechanical recording, photocopying, translation, or by any other means, known or yet unknown, for any purpose except brief quotations in reviews, without the previous written permission of Liturgical Press, Saint John’s Abbey, P.O. Box 7500, Collegeville, Minnesota 56321-7500. Printed in the United States of America. 123456789 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Bolin, Thomas M. -

Studying the Bible: the Tanakh and Early Christian Writings

Kansas State University Libraries New Prairie Press NPP eBooks Monographs 2019 Studying the Bible: The Tanakh and Early Christian Writings Gregory Eiselein Kansas State University Anna Goins Kansas State University Naomi J. Wood Kansas State University Follow this and additional works at: https://newprairiepress.org/ebooks Part of the Biblical Studies Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 4.0 License Recommended Citation Eiselein, Gregory; Goins, Anna; and Wood, Naomi J., "Studying the Bible: The Tanakh and Early Christian Writings" (2019). NPP eBooks. 29. https://newprairiepress.org/ebooks/29 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Monographs at New Prairie Press. It has been accepted for inclusion in NPP eBooks by an authorized administrator of New Prairie Press. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Studying the Bible: The Tanakh and Early Christian Writings Gregory Eiselein, Anna Goins, and Naomi J. Wood Kansas State University Copyright © 2019 Gregory Eiselein, Anna Goins, and Naomi J. Wood New Prairie Press, Kansas State University Libraries Manhattan, Kansas Cover design by Anna Goins Cover image by congerdesign, CC0 https://pixabay.com/photos/book-read-bible-study-notes-write-1156001/ Electronic edition available online at: http://newprairiepress.org/ebooks This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial 4.0 International (CC-BY NC 4.0) License http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ Publication of Studying the Bible: The Tanakh and Early Christian Writings was funded in part by the Kansas State University Open/Alternative Textbook Initiative, which is supported through Student Centered Tuition Enhancement Funds and K-State Libraries. -

Ezra Reads The

Lesson 126 Ezra Reads The Law Nehemiah 8:1-9:5 MEMORY VERSE NEHEMIAH 9:5 “S tand up and bless the LORD your God forever and ever! Blessed be Your glorious nam e, which is exalted above all blessing and praise!” WHAT YOU WILL NEED: A small mirror. A couple of large bed sheets and as an option, several sheets of green or brown construction paper for leaves and branches. Enough copies of the Mini-Scrolls template to give one scripture strip to each child in your class, one straw for each child and tape. ATTENTION GETTER! Looking In a Mirror Have your class sit down in a circle. Ask the children to remember when they woke up this morning and looked into a mirror, what did they see? Did anything need to be changed from what they saw? What did they do about what they saw in the mirror (maybe mom or dad helped)? What do mirrors help us to see? Before class, set a small mirror in a Bible. Pass the Bible around from child to child and open it to the place where the mirror is. Tell each of them not to shout out what they see. When everyone has had an opportunity to see it, then ask the class as a whole what they saw (a mirror). Read James 1:22-25 and ask them how is the Word of God like a mirror. What kinds of things do we see? What can we do about those things we see in our lives that need changing? LESSON TIME! In previous lessons, we have introduced Nehemiah and Ezra. -

The Book of Ezra Chapter 8 in 458 BC, Over Fifty Years After the Temple

Restoration of Exiles: The Book of Ezra Chapter 8 In 458 BC, over fifty years after the Temple was completed in 516 BC, Ezra himself leads another procession of the captive Jews back to Jerusalem. Ezra was a priest and teacher, devoted to studying, observing, and teaching God’s Law. King Artaxerxes, king of Persia from 465-424 BC, authorized this trip for the purposes of checking on the welfare of the people who had gone back previously, offering sacrifice to God, and appointing leaders to create a just society based on God’s Law. He also provided gold and silver, returned the articles that the Babylonians had captured from Jerusalem over a century before, gave permission for Ezra to raise additional funds for his mission, and instructed the local leaders around Jerusalem to provide additional support and not to tax them. Ezra 8 contains three sections: 1) the names of those who went with Ezra (8:1-14), 2) additional preparations Ezra made just outside Babylon (8:15-30), and 3) the actual trip and arrival back in Jerusalem (8:31-36). 8:1-14 lists other captives who went back to Jerusalem with Ezra. Read if you wish. Ezra brings the caravan out to a place near Babylon where they camp for three days to make additional preparations for the trip. This includes: Getting the right people they need for the trip (8:15-20). He reviews the people and priests who are going and realizes they need more Levities. The Levites in general were “ministers for the house of God” (8:17). -

Nehemiah 8:9-18 3Ad Sermon 2018 Hush! Today Is Holy

Nehemiah 8:9-18 3Ad Sermon 2018 Hush! Today is holy. Nehemiah 8:9-18 9Then Nehemiah the governor, Ezra the priest and scribe, and the Levites, who helped the people understand, said to all the people, “Today is holy to the LORD your God. Do not mourn or cry!” because all the people were crying as they heard the words of the Law. 10Nehemiah0020said to them, “Go, eat rich food and drink sweet drinks and send portions to those who have nothing prepared, because today is holy to our Lord. Do not grieve, because the joy of the LORD is your strength.” 11Then the Levites silenced all the people, saying, “Hush! Today is holy. Do not grieve.” 12All the people went to eat and drink and to send portions to others and to celebrate with great joy, because they understood the words that had been made known to them. 13Now on the second day, the heads of the families of all the people, the priests, and the Levites were gathered around Ezra the scribe to study the words of the Law. 14They found written in the Law, which the LORD had commanded by the hand of Moses, that the Israelites should dwell in temporary shelters during the festival of the seventh month, 15and that they should proclaim this and make this announcement in all their cities and in Jerusalem: “Go out to the mountains and bring branches from olive trees, wild olive trees, myrtle bushes, date palms, and leafy trees to make shelters, as it is written.” 16So the people went out and brought branches and made shelters for themselves. -

Jewish Theological Writings

Jewish Theological Writings This article is an outline introduction to the written and oral Torahs were considered to major lines of Jewish theological literature. You have been given to Moses on Mt. Sinai. should also study these other topics: The Targums 1 TOPIC: JEWISH LITERATURE The Targums were explanations of the TOPIC: THE APOCRYPHA Hebrew, translations and paraphrases of the Hebrew in the Chaldean language, for Jews who Wikipedia has excellent articles on most of the no longer understood Hebrew. The word means concepts listed here and is an excellent “explanation” or “interpretation”. A 2 resource for further study. combination of Chaldean and Hebrew languages became the Aramaic language. Basic listing of Jewish literature Many Jews of the Babylonian captivity had 1. Torah adopted the Aramaic language, both in the 2. Targums areas of captivity and in Jerusalem itself. The Jewish worship also had shifted from temple- 3. Talmud centered worship to several other things: 4. Mishnah Study of the Law in common 5. Gemara Chanting of Psalms, and united prayers 6. Midrash The common language used in worship was 7. Halakhah usually Aramaic. 8. Haggadah The three basic Targums of the Old Testament are: 9. Septuagint 1. The Targum on the Pentateuch, known as 10. Aquila’s Greek Version the Targum of Onkelos, about 70 AD 11. Apocrypha 2. The Targum on the Prophets, the Targum of 12. Pseudepigrapha Jonathan ben Uzziel, a student of the school st 13. Philo’s Canons of Hillel, first half of the 1 century AD. 3. The Targum on the Writings, or The Torah Hagiographa; includes Psalms, Proverbs, The Torah is the name given to the canon of Job, Chronicles, Esther Hebrew scriptures.