Bobbi Jo Boyd, Embracing Our Public Purpose

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Journal 13,3

THE NORTH CAROLINA STATE BAR FALL JOURNAL2008 The Long Road to Founding the North Carolina State Bar B Y J OHN B. MC M ILLAN he first efforts to organize the lawyers of North Carolina occurred in the 1880s, but that effort failed to take root. Then on the evening of February10,T 1899, a group of more than 65 lawyers from across the state met in the Supreme Court chambers in Raleigh and gave birth to what is now the North Carolina Bar Association.1 The early 1900s marked the beginning of In 1921, North Carolina Bar Dave Cutler/Images.com landmark changes in the legal profession Association President Thomas W. across the country. Initiatives included the Davis called on the lawyers of the state to cre- ther the Supreme Court nor the legislature establishment of standards of legal ethics (in ate a mandatory bar. "Davis envisioned a responded. The Bar Association's Committee 1908 the American Bar Association adopted state bar organization—to which all practic- on Legal Education and Admission to the Bar its "Canons of Legal Ethics"), formulation of ing attorneys would belong—as a means to suggested that each applicant to the bar at requirements for admission to the bar, and regulate legal education; to control the licens- least have a high school education or its tackling the issue of the discipline and disbar- ing and disbarment of attorneys; and to ele- equivalent. "The Court failed to respond to ment of lawyers. In those days the courts of vate the reputation of the profession in the this suggestion, just as it had failed to respond the various states controlled the admission of public mind."3 to Dean Gulley's proposals in 1910. -

Introduction

INTRODUCTION Nationally, approximately 40% of new attorneys work at firms consisting of more than 50 lawyers. Therefore, a large percentage of practicing attorneys work for small firms (fewer than 50 attorneys). Small firms generally do not have formalized recruiting procedures or a set “hiring season” when they recruit summer law clerks, school-year law clerks, or entry-level attorneys. Instead, these firms hire on an as-needed basis, and they hire year round. To secure employment with a small firm, students and lawyers alike need to be proactive in getting their name and interests out in the community. Applicants should not only apply directly to these firms, but they should connect via law school, community, and bar association activities. In this directory, you will find state-by-state hyperlinks to regional directories, bar associations, newspapers, and job banks that can be used to jump-start a small firm search. ALABAMA State/Regional Bar Associations Alabama Bar Association: http://www.alabar.org Birmingham Bar Association: http://www.birminghambar.org Mobile Bar Association: http://www.mobilebar.org Specialty Bar Associations Alabama Defense Lawyers Association: http://www.adla.org Alabama Trial Lawyers Association: http://www.alabamajustice.org Major Newspapers Birmingham News: http://www.al.com/birmingham Mobile Register: http://www.al.com/mobile Legal & Non-Legal Resources & Publications State Lawyers.com: http://alabama.statelawyers.com EINNEWS: http://www.einnews.com/alabama Birmingham Business Journal: http://birmingham.bizjournals.com -

Journal 23,4 Layout 1

THE NORTH CAROLINA STATE BAR WINTER JOURNAL2018 IN THIS ISSUE Our New President, G. Gray Wilson page 5 One Last Outlook page 8 Recovering from Disaster page 20 THE NORTH CAROLINA STATE BAR JOURNAL FEATURES Winter 2018 Volume 23, Number 4 5 An Interview with the State Bar’s New Editor President, G. Gray Wilson Jennifer R. Duncan 8 One Last Outlook—An Interview with Retiring Executive Director L. Thomas Lunsford II © Copyright 2018 by the North Carolina State Bar. All rights reserved. Periodicals 12 Summer Session: The Morganton postage paid at Raleigh, NC, and additional Decisions, 1847-1861 offices. Opinions expressed by contributors By Thomas P. Davis are not necessarily those of the North Carolina State Bar. POSTMASTER: Send 18 Counselor address changes to the North Carolina State By Ryan Stowe Bar, PO Box 25908, Raleigh, NC 27611. The North Carolina Bar Journal invites the 20 Recovering from Disaster: “Helpers” submission of unsolicited, original articles, in the Legal Community Respond essays, and book reviews. Submissions may By Mary Irvine be made by mail or email (jduncan@ ncbar.gov) to the editor. Publishing and edi- 22 Running Man torial decisions are based on the Publications By G. Gray Wilson Committee’s and the editor’s judgment of the quality of the writing, the timeliness of the article, and the potential interest to the readers of the Journal. The Journal reserves the right to edit all manuscripts. The North Carolina State Bar Journal (ISSN 10928626) is published four times per year in March, June, September, and December under the direction and supervision of the council of the North Carolina State Bar, PO Box 25908, Raleigh, NC 27611. -

A Comparative Analysis of Rulemaking Procedures and Transparency Practices of Lawyer-Licensing Entities

Campbell University School of Law Scholarly Repository @ Campbell University School of Law Scholarly Works Faculty Scholarship 2017 Do It in the Sunshine: A Comparative Analysis of Rulemaking Procedures and Transparency Practices of Lawyer-Licensing Entities Bobbi Jo Boyd Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.campbell.edu/fac_sw Part of the Legal Profession Commons Do IT IN THE SUNSHINE: A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF RULEMAKING PROCEDURES AND TRANSPARENCY PRACTICES OF LAWYER-LICENSING ENTITIES Bobbi Jo Boyd INTRODUCTION Regulation of occupational licensing has garnered national attention.) During the last sixty years, the number of occupations regulated by governmental entities has notably increased.2 As the number of regulated occupations increases, employment opportunities and wages for individuals who cannot afford or otherwise meet licensing requirements decrease. 3 In addition to concerns linked to the growing number of occupations requiring licensure, private4 and governmental5 1. U.S. DEP'T OF THE TREASURY OFFICE OF ECON. POLICY, THE COUNCIL OF ECON. ADVISERS, & THE DEP'T OF LABOR, OCCUPATIONAL LICENSING: A FRAMEWORK FOR POLICYMAKERS 3, 6, 17, (2015), https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov /sites /default /files /docs/licensing-report finalnonembargo.pdf [https://perma.cc/8DGS-FNCL] [hereinafter OCCUPATIONAL LICENSING: A FRAMEWORK FOR POLICYMAKERS]. 2. Since the 1950s, states have increasingly assumed responsibility for regulating professions practiced within their borders. See Morris M. Kleiner & Alan B. Krueger, Analyzing the Extent and Influence of OccupationalLicensing on the Labor Market, 31 J. LAB. ECON. S173, S175-S176 (2013). Between 1952 and 2008, the number of recorded occupations requiring a license leapt from less than 5% to 29%. See id. -

At Home Page 24

THE MAGAZINE OF THE UNIVERSITY OF NORTH CAROLINA AT CHAPEL HILL SCHOOL OF LAW CAROLINA LAW Making a Difference at Home page 24 VOLUME 37, ISSUE TWO FALL-WINTER 2013 UNC Law Alumni Association Board of Directors DEAN’S MESSAGE Executive Officers Thomas F. Taft ’72, president Craig T. Lynch ’86, vice president Dear Friends: Leslie C. Packer ’86, second vice president We spend much time at Carolina Law pondering pedagogy and John Charles Boger ’74, secretary-treasurer the future of the law, asking what we can do as educators — through Harriett J. Smalls ’99, Law Foundation chair classes, clinics, externships and extracurricular offerings — to Marion A. Cowell Jr. ’64, past campaign chair strengthen lawyers-in-training and mold them into outstanding members of the legal profession. In this issue of Carolina Law, David M. Moore II ’69, past president (2007-08) we set down the theme of future proficiency to focus on present John S. Willardson ’72, past president (2008-09) service — examining what our promising students, our energetic Norma R. Houston ’89, past president (2009-10) faculty, and our 10,000 living alumni, are doing right now to serve Ann Reed ’71, past president (2010-11) the people and institutions of the State of North Carolina. It’s a remarkable picture. In scores of ways, Carolina Law Robert A. Wicker ‘69, past president (2011-12) EXUM STEVE students reach out every day, fall, spring and summer, to assist John Charles “Jack” Boger families and individuals who have desperate, unmet legal needs. In our six law school clinics, students respond directly — even as they learn how to become Committee Chairs outstanding lawyers — by investigating consumer fraud that may have jeopardized a family’s home Advancement Committee, Walter D. -

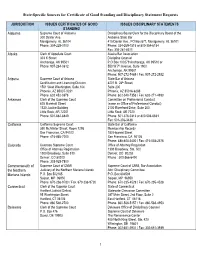

State-Specific Sources for Certificate of Good Standing and Disciplinary Statement Requests

State-Specific Sources for Certificate of Good Standing and Disciplinary Statement Requests JURISDICTION ISSUES CERTIFICATES OF GOOD ISSUES DISCIPLINARY STATEMENTS STANDING Alabama Supreme Court of Alabama Disciplinary Board Clerk for the Disciplinary Board of the 300 Dexter Ave. Alabama State Bar Montgomery, AL 36104 415 Dexter Ave., PO Box 671, Montgomery, AL 36101 Phone: 334-229-0700 Phone: 334-269-1515 or 800-354-6154 Fax: 334-261-6311 Alaska Clerk of Appellate Court Alaska Bar Association 303 K Street Discipline Counsel Anchorage, AK 99501 P.O Box 100279 Anchorage, AK 99510 or Phone: 907-264-0612 550 W 7th Avenue, Suite 1900 Anchorage, AK 99501 Phone: 907-272-7469 / Fax: 907-272-2932 Arizona Supreme Court of Arizona State Bar of Arizona Certification and Licensing Division 4201 N. 24th Street, 1501 West Washington, Suite 104 Suite 200 Phoenix, AZ 85007-3231 Phoenix, AZ 85016-6288 Phone: 602 452-3378 Phone: 602-340-7353 / Fax: 602-271-4930 Arkansas Clerk of the Supreme Court Committee on Professional Conduct 625 Marshall Street (same as Office of Professional Conduct) 1320 Justice Building 2100 Riverfront Drive, Suite 200 Little Rock, AR 72201 Little Rock, AR 7220 Phone: 501-682-6849 Phone: 501-376-0313 or 800-506-6631 Fax: 501-376-3438 California California Supreme Court State Bar of California 350 McAllister Street, Room 1295 Membership Records San Francisco, CA 94102 180 Howard Street Phone: 415-865-7000 San Francisco, CA 94105 Phone: 888-800-3400 / Fax: 415-538-2576 Colorado Colorado Supreme Court Office of Attorney Regulation Office of Attorney Registration 1300 Broadway, Ste. -

Summer 2015 NC Bar Journal

THE NORTH CAROLINA STATE BAR SUMMER JOURNAL2015 IN THIS ISSUE Reflections from Two Former District Attorneys page 11 Raising Issues of Race page 18 Meet the Federal Judges page 32 THE NORTH CAROLINA STATE BAR JOURNAL Summer 2015 FEATURES Volume 20, Number 2 Editor 11 Reflections from Two Former Jennifer R. Duncan District Attorneys—Interviews Publications Committee with Gilchrist and Grannis Dorothy Bernholz, Chair By Forrest Ferrell, Margaret Dickson, and Nancy Black Norelli, Vice-Chair Harold “Butch” Pope John A. Bowman W. Edward Bunch 18Identifying and Raising Meritorious Harry B. Crow Margaret H. Dickson Claims of Racial Bias—A Manual Rebecca Eggers-Gryder Forrest A. Ferrell for Defense Attorneys and Other John Gehring Court Actors James W. Hall By Melzer Morgan Anna Hamrick Darrin D. Jordan Sonya C. McGraw 20 Young Lawyers Start Career Paths Robert Montgomery by Embracing Pro Bono Harold (Butch) Pope By Mary Irvine G. Gray Wilson Alan D. Woodlief Jr. 24The Charlotte School of Law— © Copyright 2015 by the North Carolina State Bar. All Public and Private Value rights reserved. Periodicals postage paid at Raleigh, NC, By Jay Conison and additional offices. Opinions expressed by contributors are not necessarily those of the North Carolina State Bar. POSTMASTER: Send address changes to the North 28Ronald Spivey—Life After the Law Carolina State Bar, PO Box 25908, Raleigh, NC 27611. By John Gehring The North Carolina Bar Journal invites the submission of unsolicited, original articles, essays, and book reviews. 301, 2, 3, 4: Your Digital Security Submissions may be made by mail or e-mail (ncbar@bell- south.net) to the editor. -

Reset? Reinvent? – Planning for the Next Stage of Your Law Practice

PLANNING FOR THE NEXT STAGE OF YOUR LAW PRACTICE Produced by the North Carolina Bar Association Professional Vitality Committee with a grant from the North Carolina Bar Foundation The Professional Vitality Committee of the North Carolina Bar Association creates sourced articles centered on reducing inherent stress and enhancing vitality in the lives of legal professionals. It offers those published resources, including this booklet, as a benefit for members of the Association. North Carolina Bar Association (NCBA) publications are intended to provide current and accurate information and are designed to assist in maintaining professional competence. Nonetheless, all original sources of authority presented in NCBA publications should be independently researched in dealing with any client’s or your own specific legal matters. Information provided in NCBA publications is for informational purposes only; nothing in this publication constitutes the provision of legal advice or services, or tax advice or services, and no attorney-client relationship is formed. Publications are distributed with the understanding that neither the NCBA nor any of its authors or employees render any legal, accounting or other professional services. The views and opinions expressed are those of the individuals and do not necessarily represent official policy, position or views of the NCBA. This booklet was written in part and reviewed as a portion of the work of the NCBA Professional Vitality Committee (PVC). Please direct comments and suggestions to the PVC Chair and the NCBA Communities Manager. See more of the PVC’s compendium of articles and blog posts at https://www.ncbar.org/members/communities/committees/ professional-vitality-committee/. -

Journal 24,4 Layout 1

THE NORTH CAROLINA STATE BAR WINTER JOURNAL2019 IN THIS ISSUE Our New President, C. Colon Willoughby Jr. page 6 Mental Health in the Legal Profession page 8 IOLTA’s Future and How You Can Help page 14 THE NORTH CAROLINA STATE BAR JOURNAL FEATURES Winter 2019 Volume 24, Number 4 6 An Interview with Our New President, Editor C. Colon Willoughby Jr. Jennifer R. Duncan 8 Mental Health in the Legal Profession: Starting a Conversation with the Lawyers of Tomorrow © Copyright 2019 by the North Carolina By Peter Nemerovski State Bar. All rights reserved. Periodicals postage paid at Raleigh, NC, and additional 10 LAP and its Regulatory Purpose offices. Opinions expressed by contributors By Robynn Moraites are not necessarily those of the North Carolina State Bar. POSTMASTER: Send 13 Book Review About Our Legacy as address changes to the North Carolina State Legal Professionals Bar, PO Box 25908, Raleigh, NC 27611. By John Phillips Little Johnston The North Carolina Bar Journal invites the submission of unsolicited, original articles, 14 What We Know and Don’t Know essays, and book reviews. Submissions may about IOLTA’s Future and How You be made by mail or email (jduncan@ ncbar.gov) to the editor. Publishing and edi- Can Help torial decisions are based on the Publications By Mary Irvine Committee’s and the editor’s judgment of 17 Life as a Small Town Lawyer—Two the quality of the writing, the timeliness of the article, and the potential interest to the Perspectives readers of the Journal. The Journal reserves By John E. Gehring and Dustin T. -

State Emeritus Pro Bono Practice Rules Updated May 2019

State Emeritus Pro Bono Practice Rules Updated May 2019 American Bar Association Commission on Law and Aging David Godfrey Senior Attorney [email protected] Emeritus pro bono practice rules encourage retired and inactive attorneys to volunteer to provide pro bono assistance to clients unable to pay for essential legal representation. Currently 44 jurisdictions have adopted emeritus pro bono rules waiving some of the normal licensing requirement for attorneys agreeing to limit their practice to volunteer service. The following chart contains essential details of the current rules. For more information see: Performance Data on Emeritus Pro Bono Practice Rules http://www.americanbar.org/content/dam/aba/administrative/law_aging/EmeritusAttorneyProBonoPracticeRulesProjectReport.authchec kdam.pdf Emeritus Attorney Programs: Best Practices and Lessons Learned http://www.americanbar.org/content/dam/aba/administrative/law_aging/emeritus_best_practices_9_27.authcheckdam.pdf State Emeritus Pro Bono Practice Rules Attorneys Required to Eligible Out-of- Work with a Malpractice Years of Dues Direct State Age (Retired, State MCLE Certified Insurance Practice Waived Supervision Contact (Adopted/Amended) Restriction Inactive, License Waived Legal Mentioned Required Required Other) Allowed Services in the Rule Program Alabama (2008) None None Inactive No Reduced No Yes No No Linda L. Lund, Director Rule 6.6 Volunteer Lawyers Program Alabama State Bar P. O. Box 671 Montgomery, Alabama 36101 Alaska (2007) None None Retired or No Waived n/a Yes No Yes program Krista Scully Bar Rule 43.2 inactive must Pro Bono Director disclose Alaska Bar Association coverage Arizona (2009) (2012) None At least 5 Retired, Yes Reduced Waived Yes Yes Yes (must Kim Bernhart A.R.S. -

State CLE Contact Information State Contact/Phone Address Alabama

State CLE Contact Information State Contact/Phone Address Alabama Alabama State Bar MCLE Alabama State Bar MCLE (334) 269-1515 P.O. Box 671 (334) 261-6310 (fax) Montgomery, AL https://www.alabar.org/cle/ 36101 Alaska Alaska State Bar Association Alaska State Bar Association (907) 272-7469 840 K Street, Suite 100 (907) 272-2932 (fax) P.O. Box 100279 [email protected] Anchorage, AK https://alaskabar.org/cle-mcle/cle-provider- 99501 information/ Arizona State Bar of Arizona - CLE State Bar of Arizona - CLE (602) 252-4804 4201 N. 24th Street, Suite 100 (602) 271-4930 (fax) Phoenix, AZ [email protected] 85016 www.azbar.org/CLE/ Arkansas Arkansas CLE Board Arkansas CLE Board (501) 374-1855 2100 Riverfront Drive, Suite 110 (501) 374-1853 (fax) Little Rock, AR https://www.arcourts.gov/administration/prof 72202 essional-programs/cle/out-state California State Bar of California, MCLE Program State Bar of California, MCLE Program (888) 800-3400 180 Howard Street [email protected] San Francisco, CA www.calbar.ca.gov/Attorneys/MCLE-CLE 94105 Colorado Colorado Supreme Court Ralph L. Carr Judicial Center Board of Cont. Legal and Judicial Education Colorado Supreme Court (303) 928-7771 Board of Cont. Legal and Judicial [email protected] Education http://www.coloradosupremecourt.com/Curre 1300 Broadway, Suite 510 nt%20Lawyers/Cle.asp# Denver, CO 80203 Connecticut Connecticut Judicial Branch MCLE Connecticut Judicial Branch MCLE (860) 223-4400 Connecticut Center for Judicial (860) 223-4488 (fax) Education [email protected] 90 Washington Street, 3rd Floor https://www.jud.ct.gov/mcle/default.htm Hartford, CT 06106 Delaware Commission on CLE of the Supreme Court of Commission on CLE of the Supreme Delaware Court of Delaware (302) 651-3941 The Renaissance Center Margot Millar 405 North King Street, Suite 420 [email protected] Wilmington, DE https://courts.delaware.gov/cle/ 19801 District of The District of Columbia Bar The District of Columbia Bar Columbia (202) 737-4700 901 4th Street, NW Dennis P. -

NCBE Bar Admissions Guide

Comprehensive Guide to Bar Admission Requirements 2020 National Conference of Bar Examiners American Bar Association Section of Legal Education and Admissions to the Bar l National Conference of 'IlI!. Bar Examiners Comprehensive Guide to Bar Admission Requirements Comprehensive Guide to Bar Admission Requirements 2020 National Conference of Bar Examiners American Bar Association Section of Legal Education and Admissions to the Bar National M!!A. a Conference of AMERICANBARASSOCIATION l Legal Education and Bar Examiners I . Admissions to the Bar Editors Judith A. Gundersen Claire J. Guback This publication represents the joint work product of the National Conference of Bar Examiners and the ABA Section of Legal Education and Admissions to the Bar. The views expressed herein have not been approved by the House of Delegates or the Board of Governors of the American Bar Association, nor has such approval been sought. Accordingly, these materials should not be construed as representing the policy of the American Bar Association. National Conference of Bar Examiners 302 South Bedford Street, Madison, WI 53703-3622 608-280-8550 • TDD 608-661-1275 • Fax 608-280-8552 www.ncbex.org Chair: Hon. Cynthia L. Martin, Kansas City, MO President: Judith A. Gundersen, Madison, WI Immediate Past Chair: Michele A. Gavagni, Tallahassee, FL Chair-Elect: Hulet H. Askew, Atlanta, GA Secretary: Suzanne K. Richards, Columbus, OH Board of Trustees: Patrick R. Dixon, Newport Beach, CA John J. McAlary, Albany, NY Augustin Rivera, Jr., Corpus Christi, TX Darin B. Scheer, Casper, WY Anthony R. Simon, Jackson, MS Hon. Phyllis D. Thompson, Washington, DC Hon. Ann A. Scot Timmer, Phoenix, AZ Timothy Y.