Thomas I. Emerson: Pillar of the Bill of Rights

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Success on Tap Alisa Bowens-Mercado Is a Brewing Pioneer

SEASONS of AUTUMN 2020 SEASONS OF NEW HAVEN SEASONS NEW HAVEN SUCCESS ON TAP ALISA BOWENS-MERCADO IS A BREWING PIONEER FUR-EVER FRIENDS LOVE CONQUERS ALL WHAT TO KNOW BEFORE WEDDINGS IN THE AGE AUTUMN 2020 AUTUMN ADOPTING A PET OF COVID Where customer focus meets community focus. Serving you and the community. Today and tomorrow. On Your Terms. We offer personal and business banking, great lending rates, and online and mobile banking. We help you look to the future with retirement savings and other services to help you thrive. Many things have changed over the past few months, but Seabury’s commitment to community We volunteer over 14,000 hours annually. The Liberty Bank Foundation is remains stronger than ever. We are ready for any situation, both on campus and off. While many all about giving back with grants, scholarships and funding for education. new protocols present unique challenges, our staff, residents and members have come together to keep everyone safe, healthy and connected. We’d love to meet you! We’re still welcoming new neighbors on campus and new members to our At Home program. Visit liberty-bank.com to learn more about us or call us to make an We’re observing social distancing with outdoor meetings, model homes designed exclusively for safe tours and promoting virtual tours. Most importantly, no one is going through this alone. As appointment at any of our branches across Connecticut. a Seabury resident or Seabury At Home member, you not only secure your future healthcare, you also become part of a community that bands together at times when it’s most needed. -

![Griswold V. Connecticut (1965) [1]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3324/griswold-v-connecticut-1965-1-1203324.webp)

Griswold V. Connecticut (1965) [1]

Published on The Embryo Project Encyclopedia (https://embryo.asu.edu) Griswold v. Connecticut (1965) [1] By: Seward, Sheraden Keywords: Reproductive rights [2] Abortion [3] Contraception [4] US Supreme Court [5] The landmark Supreme Court case, Griswold v. Connecticut [6] (1965), gave women more control over their reproductive rights [7] while also bringing reproductive and birth control [8] issues into the public realm and more importantly, into the courts. Bringing these issues into the public eye allowed additional questions about the reproductive rights [7] of women, such as access to abortion [9], to be asked. This court case laid the groundwork for later cases such as Eisenstadt v. Baird (1972) and Roe v. Wade [10] (1973). Estelle Griswold [11], the executive director of the Planned Parenthood League of Connecticut (PPLC), and Dr. C. Lee Buxton [12], the director of Yale University’s infertility [13] clinic, were charged and convicted in 1962 of violating the 1879 Connecticut anti-contraception [14] law. This anti-contraception [14] law made it illegal for any person to use contraceptives or help another person obtain contraceptives. Any person found guilty of violating this law could be fined and/or imprisoned. The law itself was the primary issue being contested in the Griswold v. Connecticut [6] case. On 29 March 1965 the oral argument of the case began with Fowler V. Harper, Tom Emerson, and Catherine Roraback as the attorneys for Griswold and Buxton and Joseph Clark as the attorney for the state of Connecticut. Emerson argued that the right to privacy was implicit in the US Constitution in the First, Third, Fourth, Fifth, and Ninth Amendments. -

Winter 2018 Reproductive Health Care

FOCUS Winter 2018 REPRODUCTIVE HEALTH CARE. It’S WHAT WE DO. Delivering Comprehensive Sex Ed in a #MeToo World Your support of sex education is shifting cultural norms The #MeToo movement has lifted the curtain on the horrible Sadly, it is not surprising that sexual assault and harassment reality that sexual harassment and assault are extremely are so pervasive in our culture given the lack of information prevalent in our society. Social media pages started flooding and education on sex and sexuality. For many young people, with the hashtag in late 2017 as many have bravely chosen these topics can be confusing and scary, especially when to share the painful details of the assault and harassment children grow up hearing that sexuality is something to hide they have endured. Even if someone didn’t share #MeToo on rather than discuss. PPSNE educators and trainers see this their page, the fact remains that one in four women and one reality in schools and communities every day. in six men will be sexually assaulted in their lifetime. #MeToo has become a teachable moment for discussing and communicating about harassment and sexual assault. At PPSNE, we are shifting cultural norms by providing opportunities for young people to learn about all aspects of human sexuality. PPSNE educators teach young people how to distinguish between healthy and unhealthy relationships. They provide skill-building opportunities using proven strategies to teach young people how to effectively communicate with friends and partners. For starters this means talking about consent and defining how sexual assault and harassment can show up in our lives. -

Utregentsscalpel Nurses, the University of Texas Nurses and Nursing Students Doctors

•.. Vol. 1, No.4 April 1976 50 cents UTregentsscalpel nurses, The University of Texas Nurses and nursing students doctors. doctor to cut an IV-cord,grabbed System Schoolof Nursing, unique charged that the action taken A state-wide nurses' .support a pair of scissors and 'cut it. ,I in the nation in its autonomous March 26 was the resul t of a meeting was called in San An- organization as a six-campus power struggle between mem- tonio in early April to discuss a Regent Nelson advocated a network of nursing schools, was bers ofthe nursing profession and course of action to be taken to return to traditional "bed-side" dissolved by a 7-2 vote of the physicians at UT's medical force the Regents to rescind their nursing care. "We are not giving University of Texas Board of schools--a struggle in which decision. The course will center enough attention to direct patient Regents. nurses say regents sided with the on the office of Governor Dolph care" he observed from his Briscoe since he appoints having been a patient himself members to the Board of recently. Regents. He also charged that UTnurses Regent Joe Nelson, a . in their progressive approach Weatherford physician and were neglecting clinical training chairman of the Medical Affairs that necessitated graduates to Committee, was the most out- take special additional' training mt. JOE NELSON' spoken proponent of the System's at UT hospitals. dissolutionwhich will subordinate tl f Luci Johnson Nugent, a former the Six nursing school branches Ne~SOtwO.uldno~gr~~~;. TO~ nursing student and chairperson under UTpresidents ofcampuses an m erview 0 'of the UT Development Board, at Austin, EI Paso, Arlington, the H~uston reporter Jan ?arso~. -

Contraception: Securing Feminism’S Promise

GW Law Faculty Publications & Other Works Faculty Scholarship 2009 Contraception: Securing Feminism’s Promise Naomi R. Cahn George Washington University Law School, [email protected] June Carbone Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.gwu.edu/faculty_publications Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Cahn, Naomi R. and Carbone, June, "Contraception: Securing Feminism’s Promise" (2009). GW Law Faculty Publications & Other Works. 369. https://scholarship.law.gwu.edu/faculty_publications/369 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in GW Law Faculty Publications & Other Works by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. "I went to the gyno when I was scared I was pregnant. We discussed protection and how I can stay safe from sexual no-nos," says Jocelyn, 15, of Houghton, MI. i've been going to planned parenthood since i became sexually active. how long ago that was is irrelevant! jokes aside, PP has been kind of like my makeshift parent. i never got "the talk," so i really have to give it up to them for schooling me in the ways of being a healthy, responsible and informed individual in my...umm...activities.1 Trish G. Los Angeles, CA. For many young women, the first trip to Planned Parenthood, a Title X clinic, or a gynecologist is an important rite of passage. Some go with a parent. Some go because they think they might have sex. Many go for the first time because they think they are already pregnant. -

Catherine G. Roraback

Catherine G. Roraback February 3, 2006; February 4, 2006 Recommended Transcript of Interview with Catherine G. Roraback (Feb. 3, 2006; Feb. 4, Citation 2006), https://abawtp.law.stanford.edu/exhibits/show/catherine-g-roraback. Attribution The American Bar Association is the copyright owner or licensee for this collection. Citations, quotations, and use of materials in this collection made under fair use must acknowledge their source as the American Bar Association. Terms of Use This oral history is part of the American Bar Association Women Trailblazers in the Law Project, a project initiated by the ABA Commission on Women in the Profession and sponsored by the ABA Senior Lawyers Division. This is a collaborative research project between the American Bar Association and the American Bar Foundation. Reprinted with permission from the American Bar Association. All rights reserved. Contact Please contact the Robert Crown Law Library at Information [email protected] with questions about the ABA Women Trailblazers Project. Questions regarding copyright use and permissions should be directed to the American Bar Association Office of General Counsel, 321 N Clark St., Chicago, IL 60654-7598; 312-988-5214. ABA Senior Lawyers Division Women Trailblazers in the Law ORAL HISTORY of CATHERINE G. RORABACK Interviewer: Carolyn Kelly Dates of Interviews: Februa_ry 3, 2006 February 4, 2006 INTERVIEW WITH CATHERINE RORABACK FEBRUARY 3, 2006 Ok, it's February 3, 2006 and I am Carolyn Kelly and I am here on a sunny afternoon in Canaan, Connecticut, not to be confused with "New Canaan", and I am talking and sitting here with Catherine Roraback, who we are going to be talking with today. -

Catherine G. Roraback and the Privacy Principle

40 |41 YLR Winter 2004 papers—deeds, filings, complaints, letters, wills—as she still To set up the litigation, Buxton recruited as plaintiffs mar- conducts all her correspondence via letter. “This office is ried women whose lives could be endangered by pregnancy. filled with papers, and I don’t want people to see them, In addition, Harper brought in a young married couple, one because it’s the most intimate details of people’s lives…. of whom was a student at YLS. At the time, Roraback says, I have never gone on email just because I got so conditioned they were only hoping to convince the Connecticut courts to on privacy issues.” carve out an exception in the law for women who needed “Privacy” is an especially meaningful word for Roraback. contraceptives for medical reasons. The most important case of her litigating career was Roraback arranged for these cases to be brought under Griswold v. Connecticut, the Supreme Court case that first pseudonyms. She filed affidavits stating who each plaintiff identified a constitutional right to privacy in 1965. The was but had the records sealed, and she promised her clients case became a foundation for later decisions with national that she would warn them if their identity was going to be impact, like Roe v. Wade and the recent Lawrence v. Texas. revealed. If necessary, says Roraback, “I would then with- draw the case to protect them, because in those days it Roraback became involved in the lineage would have been socially very difficult. I got the court’s per- of legal action that led to Griswold in 1958, when Yale Law mission to handle it that way….I invented a procedure and, In Control School Professor Fowler Harper called and asked for her afterwards, lawyers from all over the state would call me to of Her Own Destiny: help, because he wasn’t a member of the Connecticut bar. -

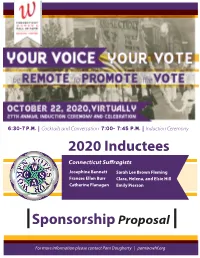

Sponsorship Opportunities

6:30-7 P.M. | Cocktails and Conversation 7:00- 8:00 P.M. | Induction Ceremony 2020 Inductees Connecticut Suffragists Josephine Bennett Sarah Lee Brown Fleming Frances Ellen Burr Clara, Helena, and Elsie Hill Catherine Flanagan Emily Pierson Sponsorship Proposal For more information please contact Pam Dougherty | [email protected] Sponsporships At - A - Glance “Did You Company Logo on Mention in Sponsor Sponsorship Welcome Commercial Know” Website, Social Media Investment Event Tickets Media Level Opportunities Video Spot Video Platforms and all Outreach (10 sec) Marketing Materials Title $10,000 Lead Sponsor 30 Seconds Unlimited Sponsorship Gold Spotlight $7,500 Activity Room 20 Seconds Unlimited Exclusive Activity Room Gold Spotlight Centenninal $7,500 20 Seconds Unlimited Exclusive Prize Package Activity Room Gold Spotlight $7,500 Mirror Mirror 20 Seconds Unlimited Premier Chat Room Gold Spotlight Women Who $7,500 20 Seconds Unlimited Premier Chat Run Room Gold Spotlight Show Me the $7,500 20 Seconds Unlimited Premier Chat Money Room General Chat Silver $5,000 15 Seconds Unlimited Room Bronze $3,000 Logo Listing Unlimited Why Your Sponsorship Matters COVID-19 has created many challenges for our community, and women and students are particularly impacted. At the Hall, we are working diligently to ensure that our educational materials are available online while parents, students, and community members work from home and that our work remains relevant to the times. We are moving forward to offer even more programs that support our community’s educational needs, from collaborating with our Partners to offer virtual educational events like at-home STEM workshops, to our new webinar series, “A Conversation Between”, which creates a forum for women to discuss issues that matter to them with leaders in our community. -

Ex-Justice Campbell: the Case of the Creative Advocate

three rime~ ~1 YCll Inc, with "ffices institution"i Prrrrllltn1 Racc; The JSSllt.' Electronic Access IJ,J:'str;1Ct InForJ11,1l!on Foe inFormation on full-text Back Issues ,11''' a""ilebk from dw MA 021 485020. the OJ III wntln\! from the holder. Authonz,lt"ln holder for iibI;lries Olld othcr COfl[aCr rhe AC3dernic ,1nd Scitncc, 350 Nhn M;1iden, MA 02I48, and of this ABC-Clio, Aca- demic Search Premier: America.' and Abs/racls Science Abstracts; CatchWord, EBSCO Academic Search Premier, EBSCO Abs/raets, [ndex 10 Periodicals and Books; Inler national Political Science Ahstracts, .!STOR, Cenler Artic/eFirsl: Online Cenler Index 10 Ahstracts. SUPREME COURT HISTORI CAL SOCIETY HONORARY CHAIRMAN William H. Rehnquist CHAIRMAN EMERITUS Dwight D. Opperman CHAIRMAN Leon Silverman PRESIDENT Frank C. Jones VICE PRESIDENTS Vincent C. Burke, Jr. Dorothy Tapper Goldman E. Barrett Prettyman, Jr. SECRETARY Virginia Warren Daly TREASURER Sheldon S. Cohen TRUSTEES George R. Adams Robert A. Gwinn Leon Polsky J. Bruce Alverson Benjamin H ei neman Harry M. Reasone r Peter G. Angelos AE. Dick Howard Bernard Reese Viccor Battaglia Robb M. Jones Charles B. Renfrew Herman Belz Randall Kennedy William Bradford Reynolds Barbara A Black Peter A. Knowles Sally Rider Hugo L. Black, Jr. Philip Allen Lacova ra H arvey Ri sh ikof Frank Boardman Gene W Lafitte Jonathan C. Rose Nancy Brennan Ral ph 1. Lancaster, Jr. Teresa Wynn Roseboro ugh Vera Brown LaSalle Le ffa II Jay Sekulow Wade Burger Jerome B. Li bin Jero ld S. Solovy Vincent C. Burke III Warren Lightfoot Kenneth Starr Edmund N. -

Overlooking Equality on the Road to Griswold Melissa Murray

THE YALE LAW JOURNAL FORUM M ARCH 2, 2015 Overlooking Equality on the Road to Griswold Melissa Murray This year marks the fiftieth anniversary of Griswold v. Connecticut,1 the Su- preme Court decision that famously articulated a right to privacy.2 As we cele- brate Griswold, it is easy to overlook what preceded it—and what was surren- dered in Griswold’s embrace of the right to privacy. In 1960, five years before Griswold reached the Supreme Court, Yale law professor Fowler V. Harper and civil rights attorney Catherine Roraback launched a series of federal challenges to Connecticut’s ban on contraceptive use and counseling. Like Griswold, these cases, Poe v. Ullman3 and Trubek v. Ullman,4 eventually reached the United States Supreme Court. The Court, however, dismissed both of these pre- Griswold challenges.5 Five years later, after the Planned Parenthood League of Connecticut opened a birth control clinic, prompting the arrests of its executive director, Estelle Griswold, and its chief physician, C. Lee Buxton,6 the Court reached the merits of the contraceptive ban in Griswold. Not surprisingly, Poe v. Ullman and Trubek v. Ullman have lived in Gris- wold’s shadow. Today, Poe v. Ullman is rarely mentioned, except as a footnote to Griswold and as an illustration of the jurisdictional requirement of ripeness. Trubek v. Ullman, which was dismissed alongside Poe,7 now receives even less 1. 381 U.S. 479 (1965). 2. Id. at 486 (“We deal with a right of privacy older than the Bill of Rights—older than our po- litical parties, older than our school system.”). -

Sponsorship Proposal 2020 Inductees

6:30-7 P.M. | Cocktails and Conversation 7:00- 7:45 P.M. | Induction Ceremony 2020 Inductees Connecticut Suffragists Josephine Bennett Sarah Lee Brown Fleming Frances Ellen Burr Clara, Helena, and Elsie Hill Catherine Flanagan Emily Pierson Sponsorship Proposal For more information please contact Pam Dougherty | [email protected] Sponsporships At - A - Glance “Did You Company Logo on Mention in Sponsor Sponsorship Welcome Commercial Know” Website, Social Media Investment Event Tickets Media Level Opportunities Video Spot Video Platforms and all Outreach (10 sec) Marketing Materials Title $10,000 Lead Sponsor 30 Seconds Unlimited Sponsorship Gold Spotlight $7,500 Activity Room 20 Seconds Unlimited Exclusive Activity Room Gold Spotlight Centenninal Prize $7,500 20 Seconds Unlimited Exclusive Package Activity Room Gold Spotlight $7,500 Mirror Mirror 20 Seconds Unlimited Premier Chat Room Gold Spotlight $7,500 Women Who Run 20 Seconds Unlimited Premier Chat Room Gold Spotlight Show Me the $7,500 20 Seconds Unlimited Premier Chat Money Room General Chat Silver $5,000 15 Seconds Unlimited Room Bronze $3,000 Logo Listing Unlimited Why Your Sponsorship Matters COVID-19 has created many challenges for our community, and women and students are particularly impacted. At the Hall, we are working diligently to ensure that our educational materials are available online while parents, students, and community members work from home and that our work remains relevant to the times. We are moving forward to offer even more programs that support our community’s educational needs, from collaborating with our Partners to offer virtual educational events like at-home STEM workshops, to our new webinar series, “A Conversation Between”, which creates a forum for women to discuss issues that matter to them with leaders in our community. -

Sponsorship Opportunities 2021 Inductees

th Wednesday, September 29 , 2021* 5:30- 8:00 P.M. * raindate Thursday, September 30th Mortensen Riverfront Plaza, 300 Columbus Boulevard, Hartford, CT 2021 Inductees Teresa C. Younger Kica Matos Jerimarie Liesegang President and CEO VP of Initiatives Tireless advocate for the Transgender of the Ms. Foundation for Women at the Vera Institute of Justice and LGBTQ+ communities in Connecticut Posthumous Inductee Sponsorship Opportunities For more information please contact Isabel Pestana | [email protected] or 203.392.9009 Sponsporship Levels Title Sponsor $15,000 • Welcome remarks at live event • Full page letter and full page ad in virtual program book • 1 minute video on air at the start of the virtual program • 15 tickets to live event • Mentions in all media outreach • Food, wine, & sparkling water for all guests provided • Logo displayed in all marketing materials and on the by the Big Green Pizza Truck and Two Pour Guys CWHF website • Unlimited virtual event tickets* Gold Sponsor $10,000 • Online 15 seconds advertisement segment during • Full page ad in virtual program book virtual program • 10 tickets to live event • Mentions in media outreach • Food, wine, & sparkling water for all guests provided • Logo displayed in all marketing materials and on the by the Big Green Pizza Truck and Two Pour Guys CWHF website • Unlimited virtual event tickets* Silver Sponsor $5,000 • Mentions in media outreach. • 5 tickets to live event • Logo displayed in all marketing materials and on the • Food, wine, & sparkling water for all guests provided CWHF website by the Big Green Pizza Truck and Two Pour Guys • ½ page ad in virtual program book • Unlimited virtual event tickets* Bronze Sponsor $3,000 • Mentions in media outreach • Food, wine, & sparkling water for all guests provided • Name listed in all marketing materials and on the by the Big Green Pizza Truck and Two Pour Guys CWHF website • Unlimited virtual event tickets* • 3 tickets to live event * Coming November 2021! CWHF will host a special online event featuring our 2021 Inductees - Leaders in Social Justice.