Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2019 Kiwikiu Conservation Translocation Report

2019 Kiwikiu Conservation Translocation Report Christopher C. Warren1, Laura K. Berthold1, Hanna L. Mounce1, Peter Luscomb2, Bryce Masuda3, Lainie Berry4 2020 Maui Forest Bird Recovery Project1 Pacific Bird Conservation2 San Diego Zoo Global3 State of Hawaiʻi, Department of Land and Natural Resources, Division of Forestry and Wildlife4 Suggested citation – Warren, C.C., L.K. Berthold, H.L. Mounce, P. Luscomb, B. Masuda. L. Berry. 2020. Kiwikiu Translocation Report 2019. Internal Report. Pages 1–101. Cover photo by Bret Mossman. Translocated female, WILD11, in Kahikinui Hawaiian Homelands. Photo credits – Photographs were supplied by Maui Forest Bird Recovery Project (MFBRP) staff, members of the press, and volunteers. Photographer credit is given for those not taken by MFBRP staff. The 2019 kiwikiu translocation was a joint operation conducted by member organizations of the Maui Forest Bird Working Group. Organizations that conducted the translocation included American Bird Conservancy, Maui Forest Bird Recovery Project, National Park Service, Pacific Bird Conservation, San Diego Zoo Global, State of Hawaiʻi Department of Land and Natural Resources – Division of Forestry and Wildlife, The Nature Conservancy of Hawai‘i, U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, and U.S. Geological Survey. In addition to representatives of these organizations, six community volunteers aided in these efforts. This does not include the dozens of volunteers and other organizations involved in planning for the translocation and preparing the release site through restoration and other activities. These efforts were greatly supported by the skilled pilots at Windward Aviation. i Table of Contents 1. Summary of 2019 Reintroduction ......................................................................................................... 1 2. Background of the Reintroduction ....................................................................................................... 1 2.1. -

Final Programmatic Environmental Impact Statement Addressing the Issuance of Incidental Take Permits for Four Wind Energy Projects in Hawai‘I

Final Programmatic Environmental Impact Statement Addressing the Issuance of Incidental Take Permits for Four Wind Energy Projects in Hawai‘i July 2019 Prepared by U.S. Department of the Interior, Fish and Wildlife Service Pacific Islands Fish and Wildlife Office 300 Ala Moana Boulevard, Room 3-122 Honolulu, HI 96850 Estimated Lead Agency Total Costs Associated with Developing and Producing this Programmatic EIS $700,000 i COVER SHEET Title of Proposed Action: Final Programmatic Environmental Impact Statement Addressing the Issuance of Incidental Take Permits for Four Wind Energy Projects in Hawaiʻi Subject: Final Programmatic Environmental Impact Statement Lead Agency: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service County/State: Honolulu, Maui, and Hawaiʻi Counties/State of Hawaiʻi Abstract: The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (Service) has received four requests for Incidental Take Permits from wind energy companies in accordance with section 10(a)(1)(B) of the Endangered Species Act of 1973, as amended (16 U.S.C. §1531 et seq.). The Applicants include: Auwahi Wind, LLC (Auwahi Wind); Kawailoa Wind, LLC (Kawailoa Wind), Kaheawa Wind Power II, LLC (KWP II); and Tawhiri Power, LLC (Pakini Nui Wind), collectively referred to as “Applicants.” The Applicants operate existing, land-based wind energy facilities on the Hawaiian Islands of Oʻahu, Maui, and Hawaiʻi. The Applicants have determined that operation and maintenance of their respective wind energy facility has the potential to result in the incidental take of one or more of the following federally listed species: the Hawaiian hoary bat (Lasiurus cinereus semotus); Hawaiian goose (Branta sandvicensis); and the Hawaiian petrel (Pterodroma sandwichensis) (collectively referred to as Covered Species). -

Maui Parrotbill, Pseudonestor Xanthophrys

STATE OF HAWAII DEPARTMENT OF LAND AND NATURAL RESOURCES Division of Forestry and Wildlife Honolulu, Hawaii 96813 March 25, 2021 Chairperson and Members Board of Land and Natural Resources State of Hawaii Honolulu, Hawaii Land Board Members: SUBJECT: INFORMATIONAL BRIEFING ON PROPOSAL TO ESTABLISH CAPTIVE POPULATION OF KIWIKIU (MAUI PARROTBILL, PSEUDONESTOR XANTHOPHRYS). This Board Submittal is an informational briefing on the current status of kiwikiu (Maui Parrotbill, Pseudonestor xanthophrys), and potential paths forward intended to forestall extinction of the species. BACKGROUND: For decades, Hawai'i has implemented bold conservation actions to save some of our most endangered birds from joining the long list of those already extinct. In the face of accelerating climate change, these actions can be challenging as the landscape on which we work to save these birds is shifting under our feet. One example of this was the loss of the translocated kiwikiu (Maui Parrotbill, Pseudonestor xanthophrys) that were reintroduced in 2019 to the Nakula Natural Area Reserve on the leeward side of Haleakala, East Maui. Kiwikiu were listed as endangered in 1967 and are threatened by habitat loss, introduced diseases, and predation by rats. Kiwikiu are restricted to a small population on the windward slopes of Haleakala that is currently in decline and at a high risk of extinction (possibly less than150 individuals). In 2006, the Hawaii Forest Bird Recovery Team, comprised of an interagency team of experts including U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and Division of Forestry and Wildlife biologists, published the Hawaii Forest Bird Recovery Plan. The plan identified captive propagation and habitat restoration to support re establishment of a kiwikiu population within its former and historic range as the highest priority recovery actions. -

Maui's Protected Areas Shelter Long-Lived Hawaiian Honeycreepers

MAUI’S PROTECTED AREAS SHELTER LONG-LIVED HAWAIIAN HONEYCREEPERS Hanna Mounce1,2, C. Robby Kohley3, Cameron Rutt3, and David Leonard4 1Maui Forest Bird Recovery Project, Makawao, HI USA 2Durrell Institute of Conservation and Ecology, University of Kent, Canterbury, Kent UK 3American Bird Conservancy, Hawaii National Park, HI USA 4Pacific Cooperative Studies Unit, Division of Forestry and Wildlife, Honolulu, HI USA Similar to the other Hawaiian Islands, Maui’s avifauna has suffered numerous extinctions. The island now only supports six honeycreeper species: Maui Parrotbill (Pseudonestor xanthophrys), Hawai‘i ‘Amakihi (Hemignathus virens), Maui ‘Alauahio (Paroreomyza montana), ‘I‘iwi (Vestiaria coccinea), ‘Ᾱkohekohe (Palmeria dolei), and ‘Apapane (Himatione sanguinea). Endemic to Maui Nui, the Maui Parrotbill, Maui ‘Alauahio, Table 1. Minimum ages for all individuals exceeding 12 years for and ‘Ᾱkohekohe are all now restricted to Maui. Maui Parrotbill, Hawai‘i ‘Amakihi, Maui ‘Alauahio, and ‘Ᾱkohekohe in Hanawi Natural Area Reserve (NAR), Maui, Hanawi Natural Area Reserve Hawai‘i. Intensive demographic monitoring has resulted in data Species Minimum Age (years) Sex Date Banded Created in 1986 as part of the Hawai‘i NARS, Hanawi NAR covers 3035 ha that extends the maximum known lifespan, i.e., longevity, on the northeastern slope of Maui’s Haleakalā Volcano. Fencing and threat Maui Parrotbill 13.48 Male 8/2/1994 for four species of these species. In addition to revising eradication conducted by NARS on Maui protects and restores forest Maui Parrotbill 13.52 Male 12/14/1997 the life history data for these honeycreepers, more than Maui Parrotbill 14.28 Male 2/8/1998 ecosystem functionality, which may have contributed to the longevity of doubling the longevity records for the three Maui Maui Parrotbill 14.54 Male 12/11/1997 the individuals presented herein. -

Billing Code 4333–15 DEPARTMENT of THE

This document is scheduled to be published in the Federal Register on 11/28/2018 and available online at https://federalregister.gov/d/2018-25634, and on govinfo.gov Billing Code 4333–15 DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Fish and Wildlife Service 50 CFR Part 10 [Docket No. FWS–HQ–MB–2018–0047; FXMB 12320900000//189//FF09M29000] RIN 1018–BC67 General Provisions; Revised List of Migratory Birds AGENCY: Fish and Wildlife Service, Interior. ACTION: Proposed rule. SUMMARY: We, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (Service), propose to revise the List of Migratory Birds protected by the Migratory Bird Treaty Act (MBTA) by both adding and removing species. Reasons for the changes to the list include adding species based on new taxonomy and new evidence of natural occurrence in the United States or U.S. territories, removing species no longer known to occur within the United States or U.S. territories, and changing names to conform to accepted use. The net increase of 59 species (66 added and 7 removed) would bring the total number of species protected by the MBTA to 1,085. We regulate the taking, possession, transportation, sale, purchase, barter, exportation, and importation of migratory birds. An accurate and up-to-date list of species protected by the MBTA is essential for public notification and regulatory purposes. DATES: We will accept comments received or postmarked on or before [INSERT DATE 60 DAYS AFTER DATE OF PUBLICATION IN THE FEDERAL REGISTER]. Comments submitted electronically using the Federal eRulemaking Portal (see ADDRESSES, below) must be received by 11:59 p.m. -

AOU Classification Committee – North and Middle America

AOU Classification Committee – North and Middle America Proposal Set 2015-A 21 Jan 2015 No. Page Title 01 02 Revise the classification of the Pipridae 02 08 Add Bicolored Wren Campylorhynchus griseus to the Main List 03 11 Move Dusky Pigeon Patagioenas goodsoni from the Appendix to the Main List 04 14 Revise the classification of the Psittaciformes 05 19 Split Pterodroma heraldica and P. atrata from Herald Petrel P. arminjoniana 06 26 Transfer American Tree Sparrow Spizella arborea to Spizelloides 07 28 Split Passerina pallidior from Painted Bunting P. ciris 08 32 Split Toxostoma arenicola from LeConte’s Thrasher T. lecontei 09 35 Correct the scientific names of (a) Leptotila cassini and (b) Amazilia saucerrottei 10 37 Split Laysan Honeycreeper from Apapane Himatione sanguinea and change its specific epithet to fraithii 11 40 Split Newell’s Shearwater Puffinus newelli from Townsend’s Shearwater P. auricularis, and consider Rapa Shearwater P. myrtae as a species separate from P. newelli 12 44 Correct the citation for Pterodroma solandri 2015-A-1 N&MA Classification Committee pp. 423-426 Revise the classification of the Pipridae Background: Our current classification of the Pipridae is as follows: Corapipo altera Chiroxiphia lanceolata Chiroxiphia linearis Xenopipo holochlora Dixiphia pipra Ceratopipra mentalis Ceratopipra erythrocephala Manacus candei Manacus aurantiacus Manacus vitellinus Lepidothrix coronata New information: Ohlson et al. (2013) investigated relationships within the family using DNA sequence data from three nuclear introns and one mitochondrial gene (ND2). They sampled all genera and most species. I have pasted in a screen grab of their tree below. Their results are largely consistent with those of previous studies except for the polyphyly of Chloropipo, members of which are in three parts of the tree. -

Survival Estimates of the Endangered Maui Parrotbill (Pseudonestor

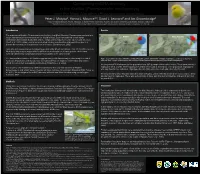

Comparing mtDNA diversity in the Kiwikiu (Psuedonestor xanthophrys) and the Maui Alauahio (Paroreomyza montana) Peter J. Motyka1, Hanna L. Mounce1,3, David L. Leonard² and Jim Groombridge3 1Maui Forest Bird Recovery Project, Makawao, HI 96768 2Pacific Cooperative Studies Unit, Division of Forestry and Wildlife, Honolulu, 96813 USA Kiwikiu 3 Durrell Institute of Conservation and Ecology, School of Anthropology and Conservation, University of Kent, Canterbury CT2 7NZ, UK Maui Alauahio Introduction Results The endangered Kiwikiu (Psuedonestor xanthophyrs) and Maui Alauahio (Paroreomyza montana) are extant insectivorous honeycreepers on the island of Maui. Both have suffered severe range Kiwikiu Maui Alauahio contractions from habitat destruction and the compounding impacts of exotic species and diseases (Scott et al. 1986). Avian malaria has decimated low and mid-elevation bird populations and is a primary threat because of its potential rise in elevation (Benning et al. 2002). Currently, 421 Kiwikiu and 55,262 Alauahio persist within 40-50 km2 (Brinck et al. 2011). Differences in life history traits may be responsible for differences in abundance of these species, which have suffered similar range contractions and are susceptible to the same threats. The low population number for Kiwikiu suggests that genetic factors may be increasing their risk of Figure 2: Locations of sampled Kiwikiu and Maui Alauahio and the distribution of unique haplotypes, each represented by a extinction. Populations with low diversity are susceptible to the impacts of inbreeding depression, different color. The pie chart displays the proportion of the sampled birds expressing each of these haplotypes. which increases their susceptibility to diseases (Frankham et al. 2002). -

Revised Recovery Plan for Hawaiian Forest Birds 2-1

II. SPECIES ACCOUNTS Section II contains accounts of all species covered in this recovery plan, presented in taxonomic order following the American Ornithologists’ Union checklist (1998). These accounts are not meant to be a complete reference, but rather to summarize sufficient relevant information about each species in order to understand the prescribed recovery strategy and the prioritization of recovery actions. All of the Hawaiian forest birds face the same set of threats, but the relative importance of those threats varies among species depending on their life history, current distribution and status, and habitat requirements. The priority placed on each component of the recovery strategy therefore varies among species. The species accounts build on and refine the overall recovery strategy discussed in the Introduction (Section I), and justify the recovery criteria presented in Section III as well as the recovery actions and priorities presented in the Recovery Actions Narrative (Section IV). Each account also includes a summary of previous and ongoing conservation efforts, including Federal and State regulations, land acquisition, research, and management directed at or relevant to the recovery of the species. All of the accounts follow the same format and contain the following section headings: description and taxonomy; life history; habitat description; historical and current range and status; reasons for decline and current threats; conservation efforts; and recovery strategy. Longer accounts for better-studied species contain additional subheadings to help locate information. When available, maps showing the historical and current distribution of the species and recovery areas appear in the accounts (Figures 6 through 21). Recovery plans are prepared following a determination that a species merits listing as endangered or threatened under the Endangered Species Act (Act). -

Critical Assessment of Habitat for Release of Maui Parrotbill

PACIFIC COOPERATIVE STUDIES UNIT UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI`I AT MĀNOA Dr. David C. Duffy, Unit Leader Department of Botany 3190 Maile Way, St. John #408 Honolulu, Hawai’i 96822 Technical Report 146 CRITICAL ASSESSMENT OF HABITAT FOR RELEASE OF MAUI PARROTBILL August 2007 1 Valerie Stein 1 University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa, Botany Department, 3190 Maile Way, St. John 101, Honolulu HI 96822 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS………………………………………………………………………..1 LIST OF TABLES AND FIGURES.................................................................................. 2 ABSTRACT .................................................................................................................... 3 INTRODUCTION............................................................................................................. 4 BACKGROUND ............................................................................................................................. 4 RESEARCH OBJECTIVES ............................................................................................................. 6 METHODS ...................................................................................................................... 8 STUDY SITE................................................................................................................................. 8 BIRD SURVEYS.......................................................................................................................... 10 VEGETATION SAMPLING-MACROHABITAT................................................................................ -

Survival Estimates of the Endangered Maui Parrotbill (Pseudonestor

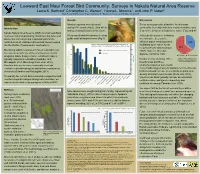

Leeward East Maui Forest Bird Community: Surveys in Nakula Natural Area Reserve Laura K. Berthold1,Christopher C. Warren1, Hanna L. Mounce1, and John P. Vetter² 1Maui Forest Bird Recovery Project, Makawao, HI 2Division of Forestry and Wildlife, Honolulu, HI Results Discussion Nineteen species were detected These surveys provide a baseline for this avian Introduction during VCP counts (Fig.2). Data will be community. Currently, Nakula is mostly nonnative; only analyzed using Distance in the future. 5 out of the 20 species found were native (Fig.2 and 4). Nakula Natural Area Reserve (NAR) on southeast Maui has been highly degraded by introduced ungulates and We grouped birds into primary feeding Although all frugivores in Nakula plants. It is currently being restored in part for the guilds and habitat preference (Fig.3). are nonnative, they can be effective native seed dispersers, reintroduction of endangered Hawaiian honeycreepers 36% like the Kiwikiu (Pseudonestor xanthophrys). 300 Figure 2. Naïve bird detections summarized from total number of 60 facilitating some native forest maximum counts at each station with total number of birds banded. recovery (Foster and Robinson 64% 250 50 Monitoring wildlife responses to forest restoration can Naïve Detections sum (max detections per station) 2007). However, they also be used as an indicator of the effectiveness of such Birds Banded 200 40 disperse nonnative fruits. Natives Non-natives programs. Birds, being sensitive to habitat changes, Figure 4. Native and non-native 150 30 typically respond to restoration (Gelarden and Kiwikiu are insectivorous. Three bird detections and captures for Detections Banded Birds insectivorous and three VCP counts/banding, n=1643. -

Northwestern Hawaiian Islands

MAUI PARROTBILL Pseudonestor xanthophrys Other: Parrot-billed Koa Finch monotypic native resident, endemic, endangered In the 1990s-mid 2010s, the Maui Parrotbill was restricted to an estimated 50 sq km area between 1,200 and 2,350 m elevation on the N slopes of Haleakala, Maui (USFWS 1984d, 2006; Scott et al. 1986; Simon et al. 1997, VanderWerf 2013a). They also showed up in the subfossil record on Moloka'i and both slopes of Mt. Haleakala down to 200 m elevation (Olson and James 1982b, James et al. 1987, James and Olson 1991), suggesting that they may have been widespread on Maui Nui before it submerged into four separate islands. Destruction of koa trees (Henshaw 1902a) and disease may have forced them relatively recently to higher elevations. Early naturalists (Rothschild 1900, Perkins 1903) noted that the parrotbill was close in structure to Hemignathus (nukupu'us; see Synonymies) but that it may also have been a transitional taxon between thin-billed and thick-billed Drepanines. Later taxonomists (e.g. Amadon 1950, Raikow 1977) considered them closer to the thick-billed honeycreepers (e.g., Psittirostra) but recent analyses suggest that the earlier naturalists were correct, its closest relative possibly being the nukupu'us and Akiapola'au (Zusi 1989; Simon et al. 1997; Fleisher et al. 1998; Pratt 2001, 2005, 2014; James 2004, Lerner et al. 2011, AOU 2015). Palmer collected the type specimen 1 Aug 1892 and, unique among Drepanines, the original scientific name Pseudonestor xanthophrys (Rothschild 1893e) has not been challenged or modified by subsequent taxonomists (see Synonymies). Early naturalists were fairly consistent in regarding Maui Parrotbill as a rare bird (Perkins 1895, 1903; Henshaw 1902a; cf. -

Acacia Koa) Ecology Forest Service and Silviculture Pacific Southwest Research Station Patrick J

United States Department of Agriculture Koa (Acacia koa) Ecology Forest Service and Silviculture Pacific Southwest Research Station Patrick J. Baker, Paul G. Scowcroft, and John J. Ewel General Technical Report PSW-GTR-211 March 2009 D E E P R A U R T LT MENT OF AGRICU The Forest Service of the U.S. Department of Agriculture is dedicated to the principle of multiple use management of the Nation’s forest resources for sustained yields of wood, water, forage, wildlife, and recreation. Through forestry research, cooperation with the States and private forest owners, and management of the National Forests and National Grasslands, it strives—as directed by Congress—to provide increasingly greater service to a growing Nation. The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, age, disability, and where applicable, sex, marital status, familial status, parental status, religion, sexual orientation, genetic information, political beliefs, reprisal, or because all or part of an individual’s income is derived from any public assistance program. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Persons with disabilities who require alternative means for communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TDD). To file a complaint of discrimination, write USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, 1400 Independence Avenue, SW, Washington, DC 20250-9410 or call (800) 795-3272 (voice) or (202) 720-6382 (TDD). USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer. Authors Patrick J. Baker was a research forester, U.S.