Mark Hibbett in Search of Doom. Tracking a Wandering Character

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Charismatic Leadership and Cultural Legacy of Stan Lee

REINVENTING THE AMERICAN SUPERHERO: THE CHARISMATIC LEADERSHIP AND CULTURAL LEGACY OF STAN LEE Hazel Homer-Wambeam Junior Individual Documentary Process Paper: 499 Words !1 “A different house of worship A different color skin A piece of land that’s coveted And the drums of war begin.” -Stan Lee, 1970 THESIS As the comic book industry was collapsing during the 1950s and 60s, Stan Lee utilized his charismatic leadership style to reinvent and revive the superhero phenomenon. By leading the industry into the “Marvel Age,” Lee has left a multilayered legacy. Examples of this include raising awareness of social issues, shaping contemporary pop-culture, teaching literacy, giving people hope and self-confidence in the face of adversity, and leaving behind a multibillion dollar industry that employs thousands of people. TOPIC I was inspired to learn about Stan Lee after watching my first Marvel movie last spring. I was never interested in superheroes before this project, but now I have become an expert on the history of Marvel and have a new found love for the genre. Stan Lee’s entire personal collection is archived at the University of Wyoming American Heritage Center in my hometown. It contains 196 boxes of interviews, correspondence, original manuscripts, photos and comics from the 1920s to today. This was an amazing opportunity to obtain primary resources. !2 RESEARCH My most important primary resource was the phone interview I conducted with Stan Lee himself, now 92 years old. It was a rare opportunity that few people have had, and quite an honor! I use clips of Lee’s answers in my documentary. -

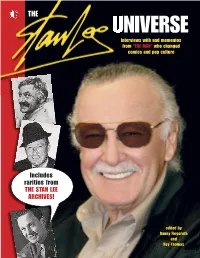

Includes Rarities from the STAN LEE ARCHIVES!

THE UNIVERSE Interviews with and mementos from “THE MAN” who changed comics and pop culture Includes rarities from THE STAN LEE ARCHIVES! edited by Danny Fingeroth and Roy Thomas CONTENTS About the material that makes up THE STAN LEE UNIVERSE Some of this book’s contents originally appeared in TwoMorrows’ Write Now! #18 and Alter Ego #74, as well as various other sources. This material has been redesigned and much of it is accompanied by different illustrations than when it first appeared. Some material is from Roy Thomas’s personal archives. Some was created especially for this book. Approximately one-third of the material in the SLU was found by Danny Fingeroth in June 2010 at the Stan Lee Collection (aka “ The Stan Lee Archives ”) of the American Heritage Center at the University of Wyoming in Laramie, and is material that has rarely, if ever, been seen by the general public. The transcriptions—done especially for this book—of audiotapes of 1960s radio programs featuring Stan with other notable personalities, should be of special interest to fans and scholars alike. INTRODUCTION A COMEBACK FOR COMIC BOOKS by Danny Fingeroth and Roy Thomas, editors ..................................5 1966 MidWest Magazine article by Roger Ebert ............71 CUB SCOUTS STRIP RATES EAGLE AWARD LEGEND MEETS LEGEND 1957 interview with Stan Lee and Joe Maneely, Stan interviewed in 1969 by Jud Hurd of from Editor & Publisher magazine, by James L. Collings ................7 Cartoonist PROfiles magazine ............................................................77 -

Relationality and Masculinity in Superhero Narratives Kevin Lee Chiat Bachelor of Arts (Communication Studies) with Second Class Honours

i Being a Superhero is Amazing, Everyone Should Try It: Relationality and Masculinity in Superhero Narratives Kevin Lee Chiat Bachelor of Arts (Communication Studies) with Second Class Honours This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The University of Western Australia School of Humanities 2021 ii THESIS DECLARATION I, Kevin Chiat, certify that: This thesis has been substantially accomplished during enrolment in this degree. This thesis does not contain material which has been submitted for the award of any other degree or diploma in my name, in any university or other tertiary institution. In the future, no part of this thesis will be used in a submission in my name, for any other degree or diploma in any university or other tertiary institution without the prior approval of The University of Western Australia and where applicable, any partner institution responsible for the joint-award of this degree. This thesis does not contain any material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference has been made in the text. This thesis does not violate or infringe any copyright, trademark, patent, or other rights whatsoever of any person. This thesis does not contain work that I have published, nor work under review for publication. Signature Date: 17/12/2020 ii iii ABSTRACT Since the development of the superhero genre in the late 1930s it has been a contentious area of cultural discourse, particularly concerning its depictions of gender politics. A major critique of the genre is that it simply represents an adolescent male power fantasy; and presents a world view that valorises masculinist individualism. -

The Empowering Squirrel Girl Jayme Horne Submitted for History of Art 390 Feminism and History of Art Professor Ellen Shortell M

The Empowering Squirrel Girl Jayme Horne Submitted for History of Art 390 Feminism and History of Art Professor Ellen Shortell Massachusetts College of Art and Design All the strength of a squirrel multiplied to the size of a girl? That must be the Unbeatable Squirrel Girl (fig. 1)! This paper will explore Marvel’s Squirrel Girl character, from her introduction as a joke character to her 2015 The Unbeatable Squirrel Girl comic series which is being harold as being extremely empowering. This paper aims to understand why a hero like Squirrel Girl would be harold and celebrated by fans, while other female heroes with feminist qualities like Captain Marvel or the New Almighty Thor might be receiving not as much praise. Squirrel Girl was created by Will Murray and artist Steve Ditko. Despite both of them having both worked for Marvel and DC, and having written stories about fan favorites like Spider-Man, Wonder Woman, Iron Man, and others, they are most known for creating Squirrel Girl, also known as Doreen Green. Her powers include superhuman strength, a furry, prehensile tail (roughly 3-4 feet long), squirrel-like buck teeth, squirrel-like retractable knuckle claws, as well as being able to communicate with squirrels and summon a squirrel army. She was first introduced in 1991, where she ambushed Iron Man in attempt to impress him and convince him to make her an Avenger. That’s when they were attacked one of Marvel’s most infamous and deadly villains, Doctor Doom. After Doctor Doom has defeated Iron Man, Squirrel Girl jumps in with her squirrel army and saves Iron Man1 (fig. -

NEDOR HEROES! $ NEDOR HEROES! In8 Th.E9 U5SA

Roy Tho mas ’Sta nd ard Comi cs Fan zine OKAY,, AXIS—HERE COME THE GOLDEN AGE NEDOR HEROES! $ NEDOR HEROES! In8 th.e9 U5SA No.111 July 2012 . y e l o F e n a h S 2 1 0 2 © t r A 0 7 1 82658 27763 5 Vol. 3, No. 111 / July 2012 Editor Roy Thomas Associate Editors Bill Schelly Jim Amash Design & Layout Jon B. Cooke Consulting Editor John Morrow FCA Editor P.C. Hamerlinck Comic Crypt Editor Michael T. Gilbert Editorial Honor Roll Jerry G. Bails (founder) Ronn Foss, Biljo White, Mike Friedrich Proofreaders Rob Smentek, William J. Dowlding Cover Artist Shane Foley (after Frank Robbins & John Romita) Cover Colorist Tom Ziuko With Special Thanks to: Deane Aikins Liz Galeria Bob Mitsch Contents Heidi Amash Jeff Gelb Drury Moroz Ger Apeldoorn Janet Gilbert Brian K. Morris Writer/Editorial: Setting The Standard . 2 Mark Austin Joe Goggin Hoy Murphy Jean Bails Golden Age Comic Nedor-a-Day (website) Nedor Comic Index . 3 Matt D. Baker Book Stories (website) Michelle Nolan illustrated! John Baldwin M.C. Goodwin Frank Nuessel Michelle Nolan re-presents the 1968 salute to The Black Terror & co.— John Barrett Grand Comics Wayne Pearce “None Of Us Were Working For The Ages” . 49 Barry Bauman Database Charles Pelto Howard Bayliss Michael Gronsky John G. Pierce Continuing Jim Amash’s in-depth interview with comic art great Leonard Starr. Rod Beck Larry Guidry Bud Plant Mr. Monster’s Comic Crypt! Twice-Told DC Covers! . 57 John Benson Jennifer Hamerlinck Gene Reed Larry Bigman Claude Held Charles Reinsel Michael T. -

When the Abyss Looks Back: Treatments of Human Trafficking in Superhero Comic Books

When the Abyss Looks Back: Treatments of Human Trafficking in Superhero Comic Books BOND BENTON AND DANIELA PETERKA-BENTON Superheroes and Social Advocacy Superhero comic book characters have historically demonstrated a developed social awareness on national and international problems. Given that the audience for superhero characters is often composed of young people, this engagement has served as a vehicle for raising understanding of issues and as a tool for encouraging activism on the part of readers (McAllister, “Comic Books and AIDS”; Thibeault). As Palmer-Mehta and Hay succinctly state: (They) have addressed a number of pressing social and political issues in narratives through the years, including alcohol and drug abuse, racism, environmental devastation, gun control, and poverty. In the process, they have provided a rich tapestry of American cultural attitudes and philosophies that reflect varying approaches to issues that continue to haunt, confound, and rile the American public (390). The relationship of the superhero to topics of ongoing public concern appears to have been present even in the earliest days of the form. In Action Comics #1, Superman attacks a man abusing his partner stating “…tough is putting mildly the treatment you’re going to get! You’re not fighting a woman now!” (Siegel and Shuster 5). On the cover of Captain America Comics #1, the Captain is shown punching Adolf Hitler over a year before the Pearl Harbor attack at a time when non-intervention was a commonly held public sentiment (Jewett and Lawrence). In 1947, the popular Superman Radio Show produced the “Clan of the Fiery Cross.” Superman’s successful defeat of the KKK was heard by over five million The Popular Culture Studies Journal, Vol. -

Two Per Cent of What?: Constructing a Corpus of Typical American Comic Books Bart Beaty, Nick Sousanis, and Benjamin Woo This Is

Two Per Cent of What?: Constructing a Corpus of Typical American Comic Books Bart Beaty, Nick Sousanis, and Benjamin Woo This is an uncorrected pre-print version of this paper. Please consult the final version for all citations: Beaty, Bart, Nick Sousanis, and Benjamin Woo. “Two Per Cent of What?: Constructing a Corpus of Typical American Comics Books.” In Wildfeuer, Janina, Alexander Dunst, Jochen Laubrock (Eds.). Empirical Comics Research: Digital, Multimodal, and Cognitive Methods (27-42). Routledge, 2018. 1 “One of the most significant effects of the transformations undergone by the different genres is the transformation of their transformation-time. The model of permanent revolution which was valid for poetry tends to extend to the novel and even the theatre […], so that these two genres are also structured by the fundamental opposition between the sub-field of “mass production” and the endlessly changing sub-field of restricted production. It follows that the opposition between the genres tends to decline, as there develops within each of them an “autonomous” sub- field, springing from the opposition between a field of restricted production and a field of mass production.” - Pierre Bourdieu, “The Field of Cultural Production” 1. Introduction Although it is asserted more strongly that it is demonstrated in his writing, Pierre Bourdieu’s notion of a “transformation of transformation-time” fruitfully points to an understanding of cultural change that seems both commonsensical and highly elusive. In the field of comic books, it is almost intuitively logical to suggest that there are stylistic, narrative, and generic conventions that are more closely tied to historical periodization than to the particularities of individual creators, titles, or publishers. -

TSR6906.Lands.Of.Dr

Table of Contents Preface and Introduction 3 Inhibitor Ray 36 Instant Hypnotism Impulser 37 Chapter 1: Inventing and Modifying Hardware 4 Insulato-Shield 37 Tech Rank 4 Intensified Molecule Projector 38 The Resource FEAT 5 Invincible Robot 38 Special Requirements 6 Ionic Blade 40 Construction Time 7 Latverian Guard Weaponry 40 The Reason FEAT 7 Memory Transference Machine 41 Kit-Bashing 7 Metabolic Transmuter 42 Modifying Hardware 8 Micro-Sentry 42 Damage 8 Mini-Missile Launcher 43 Damage to Robots 9 Molecular Cage 43 Long-Term Repairs 9 Molecule Displacer 43 Reprogramming 9 Multi-Dimensional Transference Center 44 Using Another Inventor's Creations 10 Nerve Impulse Scrambler 45 Mixing Science and Sorcery 10 Neuro-Space Field 45 Neutro-Chamber 45 Chapter 2: Doom's Technology Catalogue 11 Omni-Missile 46 Air Cannon 13 Pacifier Robot 46 Amphibious Skycraft 13 Particle Projector 47 Antimatter Extrapolator 14 Plasteel Sphere 48 Aquarium Cage 14 Plasti-Gun 48 Armor, Doom's Original 14 Power Dampener 49 Armor, Doom's Promethium 17 Power Sphere 49 Bio-Enhancer 17 Power Transference Machine 50 Body Transferral Ray 17 Psionic Refractor 50 Bubble Ship 18 Psycho-Prism 51 Concussion Ray 18 Rainbow Missile 52 Cosmic-Beam Gun 19 Reducing Ray 52 Doombot 19 Refrigeration Unit 53 Doom-Knight 21 Ring Imperial 53 Doomsman I 22 Robotron 53 Doomsman II 23 Saucer-Ship 54 Doom Squad 23 Seeker 54 Electro-Shock Pistol 24 Silent Stalker 55 Electronic Shackle 25 Sonic Drill 55 Energy Fist 25 Spider-Finder 56 Enlarger Ray 25 Spider-Wave Transmitter 56 Excavator -

VICTOR FOX? STARRING: EISNER • IGER BAKER • FINE • SIMON • KIRBY TUSKA • HANKS • BLUM Et Al

Roy Tho mas ’ Foxy $ Comics Fan zine 7.95 No.101 In the USA May 2011 WHO’S AFRAID OF VICTOR FOX? STARRING: EISNER • IGER BAKER • FINE • SIMON • KIRBY TUSKA • HANKS • BLUM et al. EXTRA!! 05 THE GOLDEN AGE OF 1 82658 27763 5 JACK MENDELLSOHN [Phantom Lady & Blue Beetle TM & ©2011 DC Comics; other art ©2011 Dave Williams.] Vol. 3, No. 101 / May 2011 Editor Roy Thomas Associate Editors Bill Schelly Jim Amash Design & Layout Christopher Day Consulting Editor John Morrow FCA Editor P.C. Hamerlinck Comic Crypt Editor Michael T. Gilbert Editorial Honor Roll OW WITH Jerry G. Bails (founder) N Ronn Foss, Biljo White 16 PAGES Mike Friedrich LOR! Proofreader OF CO Rob Smentek Cover Artist David Williams Cover Colorist Contents Tom Ziuko Writer/Editorial – A Fanzine Is As A Fanzine Does . 2 With Special Thanks to: Rob Allen Allan Holtz/ The Education Of Victor Fox . 3 Heidi Amash “Stripper’s Guide” Richard Kyle’s acclaimed 1962 look at Fox Comics—and some reasons why it’s still relevant! Bob Andelman Sean Howe Henry Andrews Bob Hughes Superman Vs. The Wonder Man 1939 . 27 Ken Quattro presents—and analyzes—the testimony in the first super-hero comics trial ever. Ger Apeldoorn Greg Huneryager Jim Beard Paul Karasik “Cartooning Was Ultimately My Goal” . 59 Robert Beerbohm Denis Kitchen Jim Amash commences a candid conversation with Golden Age writer/artist Jack Mendelsohn. John Benson Richard Kyle Dominic Bongo Susan Liberator Mr. Monster’s Comic Crypt! The Mystery Of Bill Bossert & Ulla Edgar Loftin The Missing Letterer . 69 Neigenfind-Bossert Jim Ludwig Michael T. -

Latverian Incursions: Dr Doom and Cold War Politics

Latverian Incursions: Dr Doom and Cold War Politics Doctor Doom is a character defined by the Cold War whose development over the next twenty years would be dictated by the American public's attitudes towards their government's changing foreign policy. He first appeared was in Fantastic Four #5 (Lee, et al., 1962), which was on newsstands in April 1962, halfway between two of the most iconic moments of the Cold War - the Checkpoint Charlie standoff of October 1961 and the Cuban Missile Crisis of October 1962. His origin story, however, would not be told for another two years, in Fantastic Four Annual #2 (Lee, et al., 1964). Stan Lee has said that this delay was deliberate, as 'it wasn't until 1964 that we really had time to do the kind of origin tale I felt Doc Doom deserved ... one that would make the reader really understand what motivated him, what had turned him into a villain, what made him the tragic, tortured tyrant he was.' (Lee, 1976) Here we are first introduced to Doom's homeland Latveria, a small East European country 'nestling in the heart of the Bavarian alps.' (Lee, et al., 1964) Right from the start Latveria is presented as a very strange place, like a fairy tale village transplanted into the real world, with Jack Kirby's illustrations showing an almost medieval world of peasant cottages and gypsy caravans. However, these gypsies are not the carefree wanderers of folk tales but rather a persecuted minority, forced to obey their rulers on pain of death. When the wife of Latveria's hereditary ruler - the Baron - falls fatally ill the police kidnap young Victor von 1 Doom's doctor father and force him to attempt to cure her. -

Achievements Booklet

ACHIEVEMENTS BOOKLET This booklet lists a series of achievements players can pursue while they play Marvel United: X-Men using different combinations of Challenges, Heroes, and Villains. Challenge yourself and try to tick as many boxes as you can! Basic Achievements - Win without any Hero being KO’d with Heroic Challenge. - Win a game in Xavier Solo Mode. - Win without the Villain ever - Win a game with an Anti-Hero as a Hero. triggering an Overflow. - Win a game using only Anti-Heroes as Heroes. - Win before the 6th Master Plan card is played. - Win a game with 2 Players. - Win without using any Special Effect cards. - Win a game with 3 Players. - Win without any Hero taking damage. - Win a game with 4 Players. - Win without using any Action tokens. - Complete all Mission cards. - Complete all Mission cards with Moderate Challenge. - Complete all Mission cards with Hard Challenge. - Complete all Mission cards with Heroic Challenge. - Win without any Hero being KO’d. - Win without any Hero being KO’d with Moderate Challenge. - Win without any Hero being KO’d with Hard Challenge. MARVEL © Super Villain Feats Team vs Team Feats - Defeat the Super Villain with 2 Heroes. - Defeat the Villain using - Defeat the Super Villain with 3 Heroes. the Accelerated Villain Challenge. - Defeat the Super Villain with 4 Heroes. - Your team wins without the other team dealing a single damage to the Villain. - Defeat the Super Villain without using any Super Hero card. - Your team wins delivering the final blow to the Villain. - Defeat the Super Villain without using any Action tokens. -

X-MEN $ Featuring Their First- 8.95 Decade Definers: in the USA LEE • KIRBY • ROTH No.120 THOMAS • ADAMS • HECK Sept

Roy Thomas’ X-uberant Comics Fanzine A HALF-CENTURY SALUTE TO THE TM X-MEN $ Featuring Their First- 8.95 Decade Definers: In the USA LEE • KIRBY • ROTH No.120 THOMAS • ADAMS • HECK Sept. TUSKA • FRIEDRICH 2013 DRAKE • BUSCEMA KANE • COLAN COCKRUM NOSTALGICNOTE: KA-ZAR’S PROBABLY IN THIS ISSUE, TOO––BUT DON’T BLINK, OR YOU’LL MISS HIM! PLUS: X-MEN TM & ©Marvel Characters, Inc. 0 8 ED 1 82658 27763 5 Vol. 3, No. 120 / September 2013 Editor Roy Thomas Associate Editors Bill Schelly Jim Amash Design & Layout Christopher Day Consulting Editor John Morrow FCA Editor If you’re viewing a Digital P.C. Hamerlinck Edition of this publication, Comic Crypt Editor PLEASE READ THIS: This is copyrighted material, NOT intended Michael T. Gilbert for downloading anywhere except our Editorial Honor Roll website. If you downloaded it from another website or torrent, go ahead and read it, and if you decide to keep it, DO THE Jerry G. Bails (founder) RIGHT THING and buy a legal download, or a printed copy (which entitles you to the Ronn Foss, Biljo White free Digital Edition) at our website or your local comic book shop. Otherwise, DELETE Mike Friedrich IT FROM YOUR COMPUTER and DO Proofreaders NOT SHARE IT WITH FRIENDS OR POST IT ANYWHERE. If you enjoy our publications enough to download them, Rob Smentek please pay for them so we can keep producing ones like this. Our digital William J. Dowlding editions should ONLY be downloaded at Cover Artists www.twomorrows.com Jack Kirby & Chic Stone Contents Cover Colorist Writer/Editorial: Not X-actly X-static, But..