A Prompt Script Study of Nineteenth-Century Legitimate Stage

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In Nineteenth-Century American Theatre: the Image

Burlesquing “Otherness” 101 Burlesquing “Otherness” in Nineteenth-Century American Theatre: The Image of the Indian in John Brougham’s Met-a-mora; or, The Last of the Pollywogs (1847) and Po-Ca-Hon-Tas; or, The Gentle Savage (1855). Zoe Detsi-Diamanti When John Brougham’s Indian burlesque, Met-a-mora; or, The Last of the Pollywogs, opened in Boston at Brougham’s Adelphi Theatre on November 29, 1847, it won the lasting reputation of an exceptional satiric force in the American theatre for its author, while, at the same time, signaled the end of the serious Indian dramas that were so popular during the 1820s and 1830s. Eight years later, in 1855, Brougham made a most spectacular comeback with another Indian burlesque, Po-Ca-Hon-Tas; or, The Gentle Savage, an “Original, Aboriginal, Erratic, Operatic, Semi-Civilized, and Demi-savage Extravaganza,” which was produced at Wallack’s Lyceum Theatre in New York City.1 Both plays have been invariably cited as successful parodies of Augustus Stone’s Metamora; or, The Last of the Wampanoags (1829) and the stilted acting style of Edwin Forrest, and the Pocahontas plays of the first half of the nineteenth century. They are sig- nificant because they opened up new possibilities for the development of satiric comedy in America2 and substantially contributed to the transformation of the stage picture of the Indian from the romantic pattern of Arcadian innocence to a view far more satirical, even ridiculous. 0026-3079/2007/4803-101$2.50/0 American Studies, 48:3 (Fall 2007): 101-123 101 102 Zoe Detsi-Diamanti -

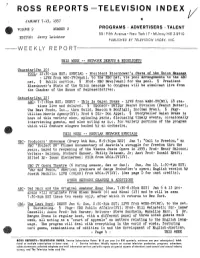

Ross Reports -Television Index

ROSS REPORTS -TELEVISION INDEX JANUARY 7-13, 1957 VOLUME NUMBER 2 PROGRAMS ADVERTISERS TALENT 551 Fifth Avenue New York 17 MUrray Hill 2-5910 EDITOR: Jerry Leichter PUBLISHED BY TELEVISION INDEX, INC. WEEKLY REPORT THIS WEEK -- NETWORK DEBUTS & HIGRT.TGHTS Thursday(Jan 10) POOL- 12:30-1pm EST; SPECIAL - President Eisenhower's State of the Union Message - LIVE fromWRC-TV(Wash), to the NBC net, via pool arrangements to the ABC net. § Public service. § Prod- NBC News(Wash) for the pool. § President Eisenhower's State of the Union message to Congress will be simulcast live from the Chamber of the House of Representatives. Saturday(Jan 12) ABC- 7-7:30pm EST; DEBUT - This Is Galen Drake - LIVE fromWABC-TV(NY), 18 sta- tions live and delayed. § Sponsor- Skippy Peanut Division (Peanut Butter), The Beet Foods, Inc., thru Guild, Bascom & Bonfigli,Inc(San Fran). § Pkgr- William Morris Agency(NY); Prod & Dir- Don Appel. § Storyteller Galen Drake is host of this variety show, spinning yarns, discussing timely events, occasionally interviewing guests, and also acting as m.c. for variety portions of the program which will feature singers backed by an orchestra. THIS WEEK -- REGULAR NETWORK SPECIALS NBC- Producers' Showcase (Every 4th Mon,8-9:30pmEST) Jan 7; "Call to Freedom," an NBC 'Project 20' filmed documentary of Austria's struggle for freedom thruthe years, keyed to reopening of the Vienna State Operain 1955; Pod- Henry Salomon; Writers- Salomon, Richard Hanser, Philip Reisman, Jr; Asst Prod- Donald Hyatt; Edited By- Isaac Kleinerman; FILM from WRCA-TV(NY). NBC TV Opera Theatre (6 during season, Sat orSun); Sun, Jan 13, 1:30-4pm EST; "War and Peace," American premiere of Serge Prokofiev's opera; English version by Joseph Machlis; LIVE (COLOR) from WRCA-TV(NY). -

Perkins, Anthony (1932-1992) by Tina Gianoulis

Perkins, Anthony (1932-1992) by Tina Gianoulis Encyclopedia Copyright © 2015, glbtq, Inc. Entry Copyright © 2007 glbtq, Inc. Reprinted from http://www.glbtq.com The life and career of actor Anthony Perkins seems almost like a movie script from the times in which he lived. One of the dark, vulnerable anti-heroes who gained popularity during Hollywood's "post-golden" era, Perkins began his career as a teen heartthrob and ended it unable to escape the role of villain. In his personal life, he often seemed as tortured as the troubled characters he played on film, hiding--and perhaps despising--his true nature while desperately seeking happiness and "normality." Perkins was born on April 4, 1932 in New York City, the only child of actor Osgood Perkins and Janet Esseltyn Rane. His father died when he was only five, and Perkins was reared by his strong-willed and possibly abusive mother. He followed his father into the theater, joining Actors Equity at the age of fifteen and working backstage until he got his first acting roles in summer stock productions of popular plays like Junior Miss and My Sister Eileen. He continued to hone his acting skills while attending Rollins College in Florida, performing in such classics as Harvey and The Importance of Being Earnest. Perkins was an unhappy young man, and the theater provided escape from his loneliness and depression. "There was nothing about me I wanted to be," he told Mark Goodman in a People Weekly interview. "But I felt happy being somebody else." During his late teens, Perkins went to Hollywood and landed his first film role in the 1953 George Cukor production, The Actress, in which he appeared with Spencer Tracy. -

“America” on Nineteenth-Century Stages; Or, Jonathan in England and Jonathan at Home

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by D-Scholarship@Pitt PLAYING “AMERICA” ON NINETEENTH-CENTURY STAGES; OR, JONATHAN IN ENGLAND AND JONATHAN AT HOME by Maura L. Jortner BA, Franciscan University, 1993 MA, Xavier University, 1998 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2005 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by It was defended on December 6, 2005 and approved by Heather Nathans, Ph.D., University of Maryland Kathleen George, Ph.D., Theatre Arts Attilio Favorini, Ph.D., Theatre Arts Dissertation Advisor: Bruce McConachie, Ph.D., Theatre Arts ii Copyright © by Maura L. Jortner 2005 iii PLAYING “AMERICA” ON NINETEENTH-CENTURY STAGES; OR, JONATHAN IN ENGLAND AND JONATHAN AT HOME Maura L. Jortner, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2005 This dissertation, prepared towards the completion of a Ph.D. in Theatre and Performance Studies at the University of Pittsburgh, examines “Yankee Theatre” in America and London through a post-colonial lens from 1787 to 1855. Actors under consideration include: Charles Mathews, James Hackett, George Hill, Danforth Marble and Joshua Silsbee. These actors were selected due to their status as iconic performers in “Yankee Theatre.” The Post-Revolutionary period in America was filled with questions of national identity. Much of American culture came directly from England. American citizens read English books, studied English texts in school, and watched English theatre. They were inundated with English culture and unsure of what their own civilization might look like. -

Giant List of Folklore Stories Vol. 5: the United States

The Giant List of Stories - Vol. 5 Pattern Based Writing: Quick & Easy Essay Skim and Scan The Giant List of Folklore Stories Folklore, Folktales, Folk Heroes, Tall Tales, Fairy Tales, Hero Tales, Animal Tales, Fables, Myths, and Legends. Vol. 5: The United States Presented by Pattern Based Writing: Quick & Easy Essay The fastest, most effective way to teach students organized multi-paragraph essay writing… Guaranteed! Beginning Writers Struggling Writers Remediation Review 1 Pattern Based Writing: Quick & Easy Essay – Guaranteed Fast and Effective! © 2018 The Giant List of Stories - Vol. 5 Pattern Based Writing: Quick & Easy Essay The Giant List of Folklore Stories – Vol. 5 This volume is one of six volumes related to this topic: Vol. 1: Europe: South: Greece and Rome Vol. 4: Native American & Indigenous People Vol. 2: Europe: North: Britain, Norse, Ireland, etc. Vol. 5: The United States Vol. 3: The Middle East, Africa, Asia, Slavic, Plants, Vol. 6: Children’s and Animals So… what is this PDF? It’s a huge collection of tables of contents (TOCs). And each table of contents functions as a list of stories, usually placed into helpful categories. Each table of contents functions as both a list and an outline. What’s it for? What’s its purpose? Well, it’s primarily for scholars who want to skim and scan and get an overview of the important stories and the categories of stories that have been passed down through history. Anyone who spends time skimming and scanning these six volumes will walk away with a solid framework for understanding folklore stories. -

Whole Document

Copyright By Christin Essin Yannacci 2006 The Dissertation Committee for Christin Essin Yannacci certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Landscapes of American Modernity: A Cultural History of Theatrical Design, 1912-1951 Committee: _______________________________ Charlotte Canning, Supervisor _______________________________ Jill Dolan _______________________________ Stacy Wolf _______________________________ Linda Henderson _______________________________ Arnold Aronson Landscapes of American Modernity: A Cultural History of Theatrical Design, 1912-1951 by Christin Essin Yannacci, B.A.; M.A. Dissertation Presented to the faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin December, 2006 Acknowledgements There are many individuals to whom I am grateful for navigating me through the processes of this dissertation, from the start of my graduate course work to the various stages of research, writing, and editing. First, I would like to acknowledge the support of my committee members. I appreciate Dr. Arnold Aronson’s advice on conference papers exploring my early research; his theoretically engaged scholarship on scenography also provided inspiration for this project. Dr. Linda Henderson took an early interest in my research, helping me uncover the interdisciplinary connections between theatre and art history. Dr. Jill Dolan and Dr. Stacy Wolf provided exceptional mentorship throughout my course work, stimulating my interest in the theoretical and historical complexities of performance scholarship; I have also appreciated their insights and generous feedback on beginning research drafts. Finally, I have been most fortunate to work with my supervisor Dr. Charlotte Canning. From seminar papers to the final drafts of this project, her patience, humor, honesty, and overall excellence as an editor has pushed me to explore the cultural implications of my research and produce better scholarship. -

1857: the Mission to Furnish Means for Episcopal Seminarians

1857: The Mission to Furnish Means for Episcopal Seminarians “The more things change the more they stay the same” might well serve as the appropriate motto for the Society for the Increase of the Ministry as it marks the 150th anniversary of its founding. SIM currently has set a course for the 21st century that requires unprecedented change in its organization and structure in order to remain faithful to its original and same purpose set forth at its founding in 1857: “The object of this corporation shall be to furnish means for the education of candidates for holy orders in the Protestant Episcopal Church of the United States.” “The Episcopal Church’s membership stood at about 400,000 in 1857 and would experience significant growth in numbers and geographical dispersion in the latter 19th century.” The need for dedicated, trained and educated ordained leaders of the Church in 2007 remains the same as in 1857, but the circumstances have changed dramatically. The United States during the term of President James Buchanan was heading for the country’s greatest crisis that would erupt into a bloody and fractious war in 1860. The frontier still beckoned settlers to fill the vast spaces that would be defended by Native Americans for several more decades. The Civil War would unleash a new wave of economic development and industrialization and the country would soon be tied together in a new way with the trans-continental railroad. Millions of immigrants would flock to our shores.A nation of 32 million has grown to the 300 million of 2006. -

Hoosiers and the American Story Chapter 3

3 Pioneers and Politics “At this time was the expression first used ‘Root pig, or die.’ We rooted and lived and father said if we could only make a little and lay it out in land while land was only $1.25 an acre we would be making money fast.” — Andrew TenBrook, 1889 The pioneers who settled in Indiana had to work England states. Southerners tended to settle mostly in hard to feed, house, and clothe their families. Every- southern Indiana; the Mid-Atlantic people in central thing had to be built and made from scratch. They Indiana; the New Englanders in the northern regions. had to do as the pioneer Andrew TenBrook describes There were exceptions. Some New Englanders did above, “Root pig, or die.” This phrase, a common one settle in southern Indiana, for example. during the pioneer period, means one must work hard Pioneers filled up Indiana from south to north or suffer the consequences, and in the Indiana wilder- like a glass of water fills from bottom to top. The ness those consequences could be hunger. Luckily, the southerners came first, making homes along the frontier was a place of abundance, the land was rich, Ohio, Whitewater, and Wabash Rivers. By the 1820s the forests and rivers bountiful, and the pioneers people were moving to central Indiana, by the 1830s to knew how to gather nuts, plants, and fruits from the northern regions. The presence of Indians in the north forest; sow and reap crops; and profit when there and more difficult access delayed settlement there. -

Report of the Chief of the Massachusetts District Police

MASS. DOCS. 312Dfc,b 02A5 COLL. 23bT 7 : ! ( / : MASSACHUSETTS .;;; II OF II i il in hill in i ooonocranomonn Full * A a.«i wk ikt-itM aoooft Public Document No. 32 EEPOET OF THE CHIEF MASSACHUSETTS DISTRICT POLICE Year ending Oct. 31, 1916, INCLUDING THE Detective, Building Inspection and Boiler Inspection Departments. BOSTON: WRIGHT & POTTER PRINTING CO., STATE PRINTERS, 32 DERNE STREET. 1917. Approved by The Supervisor of Administration. "In ®t]e CommontDealtf) of itta00act)usette. Office of the Chief of the District Police, Boston, Jan. 1, 1917. To His Excellency Samuel W. McCall, Governor, The Commonwealth of Massachusetts. Sir: — In accordance with the provisions of chapter 108 of the Revised Laws I respectfully submit to Your Excel- lency a report of the work performed by the members of the District Police Force for the year ending Oct. 31, 1916. Very respectfully, your obedient servant, Chief of the District Police. Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2010 with funding from Boston Library Consortium Member Libraries http://www.archive.org/details/reportofchiefofm1916mass REPORT. The District Police Force. The District—Police Force, as established by law, is made up as follows : The Chief, who has command and supervision of the entire Force. The detective department, consisting of a deputy chief, a captain of the steamer "Lexington," a chief fire inspector, fifteen detective officers and eleven fire inspectors. The building inspection department, consisting of a deputy chief, a supervisor of plans and seventeen building inspectors. The boiler inspection department, consisting of a deputy chief and twenty-four boiler inspectors. The Clerical Force. The clerical force consists of a first and second clerk, one clerk and fifteen stenographers, six of whom are employed in the branch offices of the Force. -

![Inmedia, 3 | 2013, « Cinema and Marketing » [Online], Online Since 22 April 2013, Connection on 22 September 2020](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3954/inmedia-3-2013-%C2%AB-cinema-and-marketing-%C2%BB-online-online-since-22-april-2013-connection-on-22-september-2020-603954.webp)

Inmedia, 3 | 2013, « Cinema and Marketing » [Online], Online Since 22 April 2013, Connection on 22 September 2020

InMedia The French Journal of Media Studies 3 | 2013 Cinema and Marketing Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/inmedia/524 DOI: 10.4000/inmedia.524 ISSN: 2259-4728 Publisher Center for Research on the English-Speaking World (CREW) Electronic reference InMedia, 3 | 2013, « Cinema and Marketing » [Online], Online since 22 April 2013, connection on 22 September 2020. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/inmedia/524 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/ inmedia.524 This text was automatically generated on 22 September 2020. © InMedia 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Cinema and Marketing When Cultural Demands Meet Industrial Practices Cinema and Marketing: When Cultural Demands Meet Industrial Practices Nathalie Dupont and Joël Augros Jerry Pickman: “The Picture Worked.” Reminiscences of a Hollywood publicist Sheldon Hall “To prevent the present heat from dissipating”: Stanley Kubrick and the Marketing of Dr. Strangelove (1964) Peter Krämer Targeting American Women: Movie Marketing, Genre History, and the Hollywood Women- in-Danger Film Richard Nowell Marketing Films to the American Conservative Christians: The Case of The Chronicles of Narnia Nathalie Dupont “Paris . As You’ve Never Seen It Before!!!”: The Promotion of Hollywood Foreign Productions in the Postwar Era Daniel Steinhart The Multiple Facets of Enter the Dragon (Robert Clouse, 1973) Pierre-François Peirano Woody Allen’s French Marketing: Everyone Says Je l’aime, Or Do They? Frédérique Brisset Varia Images of the Protestants in Northern Ireland: A Cinematic Deficit or an Exclusive -

Opernaufführungen in Stuttgart

Opernaufführungen in Stuttgart ORIGINALTITEL AUFFÜHRUNGSTITEL GATTUNG LIBRETTIST KOMPONIST AUFFÜHRUNGSDATEN (G=Gastspiel)(L=Ludwigsburg)(C=Cannstatt) Euryanthe Euryanthe Oper Helemine von Chezy C(arl M(aria) von 1833: 13.03. ; 28.04. - 1863: 01.02. - 1864: 17.01. - Weber 1881; 12.02. (Ouverture) - 1887: 20.06 (Ouverture) - 1890: 16.02. ; 26.03. ; 25.09. ; 02.11. - 1893: 07.06 - Abu Hassan Oper in 1 Akt Franz Karl Hiemer Carl Maria von Weber 1811: 10.07. - 1824: 08.12. - 1825: 07.01. Achille Achilles Große heroische Nach dem Ferdinand Paer 1803: 30.09. ; 03.10. ; 31.10. ; 18.11. - 1804: Oper in 3 Akten Italienischen des 23.03. ; 18.11. - 1805: 17.06. ; 03.11. ; 01.12. - Giovanni DeGamerra 1806: 18.05. - 1807: 14.06. ; 01.12. - 1808: 18.09. - von Franz Anton 1809: 08.09. - 1810: 01.04. ; 29.07. - 1812: 09.02. ; Maurer 01.11. - 1813: 31.10. - 1816: 11.02. ; 09.06. - 1817: 01.06. - 1818: 01.03. - 1820: 15.01. - 1823: 17.12. - 1826: 08.02. Adelaide di Adelheit von Guesclin Große heroische Aus dem Italienischen Simon Mayr 1805: 21.07. ; 02.08. ; 22.09. - 1806: 02.03. ; 14. 09. Guescelino Oper in 2 Akten ; 16.09. (L). - 1807: 22.02. ; 30.08.(L) ; 06.09. - 1809: 07.04. - 1810: 11.04. - 1814: 28.08.(L) ; 09.10. - 1816: 05.05. ; 18.08. Adelina (auch Adeline Oper in 1 Akt Nach dem Pietro Generali 1818: 23.03. Luigina, Luisina) Italienischen von Franz Karl Hiemer - Des Adlers Horst Romantisch- Carl von Holtei Franz Gläser 1852: 30.04. ; 02.05. -

United States Theatre Programs Collection O-016

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8s46xqw No online items Inventory of the United States Theatre Programs Collection O-016 Liz Phillips University of California, Davis Library, Dept. of Special Collections 2017 1st Floor, Shields Library, University of California 100 North West Quad Davis, CA 95616-5292 [email protected] URL: https://www.library.ucdavis.edu/archives-and-special-collections/ Inventory of the United States O-016 1 Theatre Programs Collection O-016 Language of Material: English Contributing Institution: University of California, Davis Library, Dept. of Special Collections Title: United States Theatre Programs Collection Creator: University of California, Davis. Library Identifier/Call Number: O-016 Physical Description: 38.6 linear feet Date (inclusive): 1870-2019 Abstract: Mostly 19th and early 20th century programs, including a large group of souvenir programs. Researchers should contact Archives and Special Collections to request collections, as many are stored offsite. Scope and Contents Collection is mainly 19th and early 20th century programs, including a large group of souvenir programs. Access Collection is open for research. Processing Information Liz Phillips converted this collection list to EAD. Preferred Citation [Identification of item], United States Theatre Programs Collection, O-016, Archives and Special Collections, UC Davis Library, University of California, Davis. Publication Rights All applicable copyrights for the collection are protected under chapter 17 of the U.S. Copyright Code. Requests for permission to publish or quote from manuscripts must be submitted in writing to the Head of Special Collections. Permission for publication is given on behalf of the Regents of the University of California as the owner of the physical items.