My Father's Advocacy for a Right to Treatment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Right to Treatment-A Fabled Right Receives Judicial Recognition in Missouri, the The

Missouri Law Review Volume 45 Issue 2 Spring 1980 Article 10 Spring 1980 Right to Treatment-A Fabled Right Receives Judicial Recognition in Missouri, The The William J. Powell Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.missouri.edu/mlr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation William J. Powell, Right to Treatment-A Fabled Right Receives Judicial Recognition in Missouri, The The, 45 MO. L. REV. (1980) Available at: https://scholarship.law.missouri.edu/mlr/vol45/iss2/10 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at University of Missouri School of Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Missouri Law Review by an authorized editor of University of Missouri School of Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Powell: Powell: Right to Treatment-A Fabled Right Receives Judicial Recognition 1980] RECENT CASES Bargaining units comprised solely of RNs are appropriate under the traditional community of interest test as well as under the St. Francis disparity of interest test, if it means taking into account public interest in avoiding undue proliferation of bargaining units. RN only units should be presumptively appropriate to discourage unnecessary delay and expense in litigation. If a disparity of interest or public interest factor is to be added to the Board's determinations of appropriate units in the health care industry, the Supreme Court needs to direct the Board to use such a test, after explaining what it is, and how to use it. The present disagreement between the Board and the courts of appeal is harmful to employees, em- ployers, and the public they serve; it benefits only labor lawyers. -

Competency, Deinstitutionalization, and Homelessness: a Story of Marginalization Michael L

digitalcommons.nyls.edu Faculty Scholarship Articles & Chapters 1991 Competency, Deinstitutionalization, and Homelessness: A Story of Marginalization Michael L. Perlin New York Law School, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.nyls.edu/fac_articles_chapters Part of the Law and Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Houston Law Review, Vol. 28, Issue 1 (January 1991), pp. 63-142 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at DigitalCommons@NYLS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles & Chapters by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@NYLS. COMPETENCY, DEINSTITUTIONALIZATION, AND HOMELESSNESS: A STORY OF MARGINALIZATION Michael L. Perlin* Table of Contents PROLOGUE: LIFE IhITATES ART ................... 64 I INTRODUCTION: CIVILIZATION'S DISCONTENTED ....... 65 II. THE MYTHS OF HOMELESSNESS ................... 70 A. Introduction .............................. 70 B. ContributingFactors ....................... 74 1. The baby boom ........................ 74 2. The shrinking housing market .......... 75 3. Reduction in governmental benefits ...... 78 4. Unemployment rates ................... 79 C. Conclusion ................................ 80 IHL THE MYTHS OF DEINSTITUTIONALIZATION ........... 80 A. HistoricalBackground ..................... 80 B. Myths and "Ordinary Common Sense"....... 88 IV. DEINSTITUTIONALIZATION AND HOMELESSNESS ....... 94 A. The Perceived Failures of Deinstitutionaliza- tion ...................................... 94 -

Where the Winds Hit Heavy on the Borderline: Mental Disability Law, Theory and Practice, Us and Them

Loyola of Los Angeles Law Review Volume 31 Number 3 Symposium on Mental Disability Law Article 12 4-1-1998 Where the Winds Hit Heavy on the Borderline: Mental Disability Law, Theory and Practice, Us and Them Michael L. Perlin Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/llr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Michael L. Perlin, Where the Winds Hit Heavy on the Borderline: Mental Disability Law, Theory and Practice, Us and Them, 31 Loy. L.A. L. Rev. 775 (1998). Available at: https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/llr/vol31/iss3/12 This Symposium is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews at Digital Commons @ Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Loyola of Los Angeles Law Review by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. "WHERE THE WINDS HIT HEAVY ON THE BORDERLINE":* MENTAL DISABILITY LAW, THEORY AND PRACTICE, "6US99 AND "6THEM"9 Michael L. Perlin** A few years ago, I began to use Bob Dylan titles and lyrics as the embarkation point for all my article and book titles.' I decided to do this in large part because it is clear to me that Dylan's utterly idiosyn- cratic "take" on the world provides us with a never-ending supply of metaphors for an analysis of any aspect of mental disability law. Among the lyrics that I have drawn on is a line from Dylan's brilliant song Idiot Wind that I used as the epigrammatic beginning of an article forthcoming in the Iowa Law Review: "The Borderline Which Separated You From Me": The Insanity Defense, the Authori- * Bob Dylan, Girl of the North County, in BOB DYLAN, LYRICS, 1962-1985, at 54 (1985). -

Civil Commitment: Recognition of Patients’ Right to Treatment, Donaldson V

Washington University Law Review Volume 1974 Issue 4 January 1974 Civil Commitment: Recognition of Patients’ Right to Treatment, Donaldson v. O’Connor, 493 F.2d 507 (5th Cir. 1974) Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_lawreview Part of the Health Law and Policy Commons, and the Law and Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Civil Commitment: Recognition of Patients’ Right to Treatment, Donaldson v. O’Connor, 493 F.2d 507 (5th Cir. 1974), 1974 WASH. U. L. Q. 787 (1974). Available at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_lawreview/vol1974/iss4/8 This Case Comment is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School at Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Washington University Law Review by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CIVIL COMMITMENT: RECOGNITION OF PATIENTS! RIGHT TO TREATMENT Donaldson v. O'Connor,493 F.2d 507 (5th Cir. 1974) Plaintiff was involuntarily civilly committed to the Florida State Men- tal Hospital in 1957.1 Before his release in 1971, he brought an action under 42 U.S.C. § 1983,2 alleging that five hospital and health officials deprived him of adequate psychiatric treatment. 3 A jury awarded com- pensatory and punitive damages against two physicians,4 and they ap- pealed. The United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit af- firmed and held: A nondangerous involuntarily committed mental pa- tient has a constitutional right to treatment. 5 1. Kenneth Donaldson was committed by a county court judge of Pinellas County, Florida, pursuant to Act of Aug. -

Pretexts and Mental Disability Law: the Case of Competency

University of Miami Law Review Volume 47 Number 3 Symposium: The Law of Competence Article 4 1-1-1993 Pretexts and Mental Disability Law: The Case of Competency Michael L. Perlin Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.miami.edu/umlr Part of the Disability Law Commons Recommended Citation Michael L. Perlin, Pretexts and Mental Disability Law: The Case of Competency, 47 U. Miami L. Rev. 625 (1993) Available at: https://repository.law.miami.edu/umlr/vol47/iss3/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at University of Miami School of Law Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Miami Law Review by an authorized editor of University of Miami School of Law Institutional Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Pretexts and Mental Disability Law: The Case of Competency MICHAEL L. PERLIN* I. INTRODUCTION ........................................................ 626 II. PRETEXTS IN THE LEGAL SYSTEM ....................................... 630 A . Introduction ....................................................... 630 B. Explaining Pretextuality ............................................. 631 C. Pretexts and Mental Disability Cases .................................. 636 III. MORALITY AND HEURISTICS: THE ROLE OF EXPERTS ..................... 640 A . Introduction ....................................................... 640 B. On M orality ....................................................... 641 1. EXPERTISE AND SOCIAL VALUES -

Xerox University Microfilms 300 North Zeeb Road Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106 75-3168

INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again — beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

From the Snake Pit to the Supreme Court: the Collapse of the Insane Asylum in Mid-20Th Century America

From the Snake Pit to the Supreme Court: The Collapse of the Insane Asylum in Mid-20th Century America Lauren Amos Advisor: Dr. Steven Noll 2 Acknowledgements My sincerest thanks to Dr. Noll, who let me borrow all of his books and take up all of his office hours. Thank you for introducing me to Phi Alpha Theta, the students at Sidney Lanier, and the entire field of disability history that I didn’t know existed. Thank you to my parents, friends, and Michael, who had to listen to me talk about asylums for a year and read countless drafts and re-drafts. A special thanks to Colleen, who let me stay at her house while I visited the Tallahassee archives. Lastly, I would like to thank the University of Florida History Department for the best undergraduate major I could have asked for, and a wonderful four years. 3 Table of Contents Introduction: A Predictable Pattern ......................................................................................... 4 Chapter 1: Shaping the Stigma ................................................................................................. 7 Chapter 2: Common Oversimplifications for Deinstitutionalization ........................................ 13 Chapter 3: An Internal Attack on Psychiatry .......................................................................... 16 Reform Rhetoric from the 1890s-1950s .......................................................................................... 16 The Rise of Anti-Psychiatry Literature ............................................................................................ -

“There's Voices in the Night Trying to Be Heard”: the Potential Impact Of

Brooklyn Law Review Volume 84 | Issue 3 Article 4 5-1-2019 “There’s Voices in the Night Trying to Be Heard”: The otP ential Impact of the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities on Domestic Mental Disability Law Michael L. Perlin Naomi M. Weinstein Follow this and additional works at: https://brooklynworks.brooklaw.edu/blr Part of the Disability Law Commons, Human Rights Law Commons, International Humanitarian Law Commons, International Law Commons, and the Jurisprudence Commons Recommended Citation Michael L. Perlin & Naomi M. Weinstein, “There’s Voices in the Night Trying to Be Heard”: The Potential Impact of the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities on Domestic Mental Disability Law, 84 Brook. L. Rev. (). Available at: https://brooklynworks.brooklaw.edu/blr/vol84/iss3/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at BrooklynWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Brooklyn Law Review by an authorized editor of BrooklynWorks. “There’s Voices in the Night Trying to Be Heard” THE POTENTIAL IMPACT OF THE CONVENTION ON THE RIGHTS OF PERSONS WITH DISABILITIES ON DOMESTIC MENTAL DISABILITY LAW Michael L. Perlin† & Naomi M. Weinstein†† INTRODUCTION We cannot consider the impact of anti-discrimination law on persons with mental disabilities without a full understanding of how sanism1 permeates all aspects of the legal system—in judicial opinions, legislation, the role of lawyers, juror decision- making—and the entire fabric of American society.2 Notwithstanding nearly thirty years of experience under the Americans with Disabilities Act,3 and an impressive corpus of constitutional case law and state statutes,4 the attitudes of judges, jurors, and lawyers often reflect the same level of bigotry † Adjunct Professor of Law, Emory University School of Law; Instructor, Loyola University New Orleans, Department of Criminology and Justice; Professor Emeritus of Law and Founding Director, International Mental Disability Law Reform Project, New York Law School. -

1955 Journal

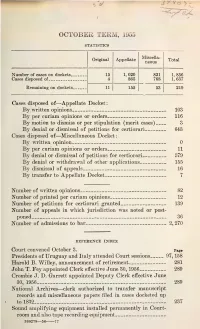

OCTOBER TERM, 1955 STATISTICS Miscella- Original Appellate Total neous Number of Gases on dockets 15 1, 020 821 1, 856 Cases disposed of 4 865 768 1, 637 Remaining on dockets. 11 155 53 219 Cases disposed of—Appellate Docket: By written opinions 103 By per curiam opinions or orders 116 By motion to dismiss or per stipulation (merit cases) 3 By denial or dismissal of petitions for certiorari 64& Cases disposed of—Miscellaneous Docket : By written opinion 0 By per curiam opinions or orders 11 By denial or dismissal of petitions for certiorari 579 By denial or withdrawal of other applications 155 By dismissal of appeals 16 By transfer to Appellate Docket 7 Number of written opinions 82 Number of printed per curiam opinions 12 Number of petitions for certiorari granted 139 Number of appeals in which jurisdiction was noted or post- poned 36 Number of admissions to bar 2, 270 REFERENCE INDEX Court convened October 3. Page Presidents of Uruguay and Italy attended Court sessions 97, 158 Harold B. Willey, announcement of retirement 281 John T. Fey appointed Clerk effective June 30, 1956 289 Crombie J. D. Garrett appointed Deputy Clerk effective June 30, 1956 289 National Archives—clerk authorized to transfer manuscript records and miscellaneous papers filed in cases docketed up to 1832 237 Sound amplifying equipment installed permanently in Court- room and also tape recording equipment 360278—56 77 Attorney : Page Motion for reinstatement of Norman J. Griffin granted and order of disbarment vacated (300 Misc.) 42 Disbarment of Orille C. Gaudette (336 Misc.) 103, 154 Change of name 88 Counsel appointed (489, 460, 714) 81, 119, 163 Special Master, compensation awarded (10 Orig.) 282 Rules of Criminal Procedure amended and reported to Con- gress 202 Opinion amended (23) 258 Orders and judgments amended (406 O. -

Mental Health in New York State, 1945-1998: a Historical Overview

MENTAL HEALTH In NEW YORK STATE 1945-1998 An Historical Overview By Bonita Weddle New York State Archives 1998 Publication Number 70 Mental Health in New York State, 1945-1998 An Historical Overview Introduction New York State has for more than one hundred years been a pioneer in the development of mental health treatment and research. Although it was not the first state to construct state- supported institutions specifically for the mentally ill, it was the first completely to relieve county and city governments of the burden of caring for their mentally ill inhabitants; the 1890 State Care Act, which placed all responsibility for the care and treatment of those suffering from mental disorders in the hands of state government, was emulated by a number of other states in subsequent years. The landmark 1954 Community Mental Health Services Act (CMHSA), which was born of the state's desire to divest itself of some of this responsibility, and policymakers' subsequent efforts to compel localities to improve care and to insure that the needs of the seriously mentally ill were being met also anticipated developments in other states and at the federal level. The reasons for the state's consistent willingness to embrace innovation are obscure, but they may stem in part from the state's large size and, in the New York City metropolitan area, population density. Gerald Grob, the leading historian of mental health policy in the United States, asserts that the development of state mental institutions was but one of many responses to industrialization, urbanization, and immigration, which rendered ineffective the personal relationships and local social institutions that had during the nation's agrarian past cared for the needy.1 New York State was among the first states to experience these sweeping changes, and as a result the need to devise effective responses to them arose sooner than it did elsewhere. -

Sanism, Pretextuality, and the Representation of Defendants with Mental Disabilities

QUT Law Review ISSN: Online- 2201-7275 Volume 16, Issue 3, pp. 106-126. DOI: 10.5204/qutlr.v16i3.689 “INFINITY GOES UP ON TRIAL”: SANISM, PRETEXTUALITY, AND THE REPRESENTATION OF DEFENDANTS WITH MENTAL DISABILITIES MICHAEL L PERLIN* I INTRODUCTION I begin by sharing a bit about my past. Before I became a professor, I spent 13 years as a lawyer representing persons with mental disabilities, including three years in which my focus was primarily on such individuals charged with crime. In this role, when I was Deputy Public Defender in Mercer County (Trenton) NJ, I represented several hundred individuals at the maximum security hospital for the criminally insane in New Jersey, both in individual cases, and in a class action1 that implemented the then-recent US Supreme Court case of Jackson v Indiana,2 that had declared unconstitutional state policy that allowed for the indefinite commitment of pre-trial detainees in maximum security forensic facilities if it were unlikely he would regain his capacity to stand trial in the ‘foreseeable future.’3 I continued to represent this population for a decade in my later positions as Director of the NJ Division of Mental Health Advocacy and Special Counsel to the NJ Public Advocate. Also, as a Public Defender, I represented at trial many defendants who were incompetent to stand trial, and others who, although competent, pled not guilty by reason of insanity.4 Finally, during the time that I directed the Federal Litigation Clinic at New York Law School, I filed a brief on behalf of appellant in Ake v Oklahoma,5 -

Half-Wracked Prejudice Leaped Forth: Sanism, Pretextuality, and Why and How Mental Disability Law Developed As It Did Michael L

digitalcommons.nyls.edu Faculty Scholarship Articles & Chapters 1999 Half-Wracked Prejudice Leaped Forth: Sanism, Pretextuality, and Why and How Mental Disability Law Developed as It Did Michael L. Perlin New York Law School, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.nyls.edu/fac_articles_chapters Part of the Disability Law Commons, and the Jurisprudence Commons Recommended Citation 10 Journal of Contemporary Legal Issues 3-36 (1999) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at DigitalCommons@NYLS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles & Chapters by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@NYLS. "Half-Wracked Prejudice Leaped Forth": Sanism, Pretextuality, and Why and How Mental Disability Law Developed as it Did MICHAEL L. PERLIN* I. INTRODUCTION If we are to come to grips with the roots of why and how mental disability law jurisprudence developed as it has, it is absolutely essential that we come to grips with two forces-sanism and pretextuality-that utterly dominate and drive this area of the law.' The papers in this symposium issue-about how we construct "craziness,"2 the therapeutic potential of the civil commitment hearing,3 the meaning of "dangerousness," 4 how we construct competence,5 the application of the Americans with Disabilities Act to persons with mental disabilities,6 the * Professor of Law, New York Law School. 1. See generally MICHAEL L. PERLIN, THE HIDDEN PREJUDICE: MENTAL DISABILITY ON TRIAL (forthcoming 1999). 2. Stephen J. Morse, Crazy Reasons, 10 J. CONTEMP. LEGAL ISSUES 189 (1999). 3. Bruce J. Winick, Therapeutic Jurisprudence and the Civil Commitment Hearing, 10 J.