Safe and Inclusive Cities Political Context, Crime and Violence In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Locating the Survivor in the Indian Criminal Justice System: Decoding the Law I

Locating the Survivor in the Indian Criminal Justice System: Decoding the Law i Locating the Survivorin the Indian Criminal Justice System: Decoding the Law LAWYERS COLLECTIVE WOMEN’S RIGHTS INITIATIVE Contents Contents v Foreword ix Acknowledgments xi Abbreviations xiii Introduction I. Kinds of Offences and Cases 2 1. Bailable Offence 2 2. Non Bailable Offence 2 3. Cognisable Offences 2 4. Non Cognisable Offences 2 5. Cognisable Offences and Police Responsibility 3 6. Procedure for Trial of Cases 3 II. First Information Report 4 1. Process of Recording Complaint 4 2. Mandatory Reporting under Section 19 of the POCSO Act 4 3. Special Procedure for Children 5 4. Woman Officer to Record Information in Specified Offences 5 5. Special Process for Differently-abled Complainant 6 6. Non Registration of FIR 6 7. Registration of FIR and Territorial Jurisdiction 8 III. Magisterial Response 9 1. Remedy against Police Inaction 10 IV. Investigation 11 1. Steps in Investigation 12 2. Preliminary, Pre-FIR Inquiry by the Police 12 Locating the Survivor in the Indian Criminal Justice System: Decoding the Law v 3. Process of Investigation 13 4. Fair Police Investigation 14 5. Statement and Confessions 14 (i) Examination and statements of witnesses 14 (ii) Confessions to the magistrate 16 (iii) Recording the confession 16 (iv) Statements to the magistrate 16 (v) Statement of woman survivor 17 (vi) Statement of differently abled survivor 17 6. Medical Examination of the Survivor 17 (i) Examination only by consent 17 (ii) Medical examination of a child 17 (iii) Medical examination report 18 (iv) Medical treatment of a survivor 18 7. -

Status of Entitlement Issued by Accountant General in July, 2020 in Respect of Gazetted Officers

ENTITLEMENTS AUTHORISED/ISSUED BY ACCOUNTANT GENERAL IN July 2020 IN RESPECT OF GAZETTED OFFICER PAY SLIP ISSUED NAME DESIGNATION STATUS Ajay Kumar अधधकण अभभययतत (ससवतभनववत) ISSUED Ajay Kumar Srivastava No-1 PRINCIPAL JUDGE, FAMILY COURT ISSUED Akhilesh Kumar District co-operative officer ISSUED Alok Kumar TECHNICAL ADVISOR ISSUED Amar Singh कतयरपतलक अभभययतत, ISSUED Amarendra Prasad Singh (भनलयभबत ) ISSUED Amrit Lal Meena अपर ममखय सभचव, ISSUED Anil Kumar Superintending Engineer, ISSUED Anil Kumar Anand Senior Reporter, ISSUED Anil Kumar Thakur Retired Medical Officer, ISSUED Anwar Hussain Member, Bihar Police Sub-ordinate Services Commission, Santosh Mansion, ISSUED B-Block, Near R.P.S. Law College, Arbind Prasad Shahi Retd District Immunisation Officer, Katihar ISSUED Arun Kumar Medical Officer, ISSUED Arun Kumar Sinha Executive Engineer, ISSUED Arun Kumar Srivastava PRINCIPAL JUDGE, FAMILY COURT ISSUED Arunish Chawla Central deputation ISSUED Arvind Kumar Pandey Principal Chief Conservator of Forests(HOFF) ISSUED Ashesh Kumar Retd. Superintendent ISSUED Ashok Kumar Chaudhary Superintending Engineer, ISSUED Ashok Kumar Jha Executive Engineer(NABARD,External Sustained), Chief Engineer(Budget & ISSUED Planning) Ashok Kumar Yadav Dy. Director, Medical Education Deptt. ISSUED Atma Nand Kumar Civil Surgeon Cum Chief Medical Officer ISSUED Awdhesh Kumar Civil Surgeon Cum Chief Medical Officer ISSUED Ayodhya Singh Additional S.P. (Operation), ISSUED Bharat Singh Professor ISSUED Bhaskar Chandra Bharti DIVISIONAL FOREST OFFICER, PURNEA ISSUED -

Governance and the Media Irum Shehreen

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by BRAC University Institutional Repository CGS Working Paper CGS WP 3 Governance and the Media Irum Shehreen Ali Background Paper for The State of Governance in Bangladesh 2006 Produced in Collaboration with Research and Evaluation Division (RED) BRAC Centre for Governance Studies BRAC University Dhaka, Bangladesh www.cgs-bu.com The Centre for Governance Studies at BRAC University seeks to foster a new generation of researchers, public administrators and citizens with critical and analytical perspectives on governance. The Centre’s State of Governance research project is devoted to providing empirical evidence and conceptual clarity about governance in Bangladesh. It seeks to demystify a contentious topic to further constructive discussion and debate. Good governance is often viewed as a means of advancing the agendas of official and multilateral development institutions. The Centre believes, however, that there is a large domestic constituency for good governance; and that governance is properly deliberated between citizens and their state rather than by the state and external institutions. The Centre’s working papers are a means of stimulating domestic discourse on governance in Bangladesh. They bring to the public domain the insights and analyses of the new generation of researchers. The initial working papers were originally developed as contributions and background papers for The State of Governance in Bangladesh 2006, the Centre’s first annual report. David Skully, Editor, CGS Working Paper Series Visiting Professor CGS-BRAC University and Fulbright Scholar Center for Governance Studies Working Paper Series CGS WP 1 Ferdous Jahan: Public Administration in Bangladesh CGS WP 2 Nicola Banks: A Tale of Two Wards CGS WP 3 Irum Shehreen Ali: Governance and the Media Research and Evaluation Division (RED) of BRAC was set up in 1975 as an independent entity within the framework of BRAC. -

Employment Act

LAWS OF KENYA EMPLOYMENT ACT CHAPTER 226 Revised Edition 2012 [2007] Published by the National Council for Law Reporting with the Authority of the Attorney-General www.kenyalaw.org [Rev. 2012] CAP. 226 Employment CHAPTER 226 EMPLOYMENT ACT ARRANGEMENT OF SECTIONS PART I – PRELIMINARY Section 1. Short title. 2. Interpretation. 3. Application. PART II – GENERAL PRINCIPLES 4. Prohibition against forced labour. 5. Discrimination in employment. 6. Sexual harassment. PART III – EMPLOYMENT RELATIONSHIP 7. Contract of service. 8. Oral and written contracts. 9. General provision of contract of service. 10. Employment particulars. 11. Statement of initial particulars. 12. Statement on disciplinary rules. 13. Statement of changes. 14. Reasonably accessible document or collective agreement. 15. Informing employees of their rights. 16. Enforcement. PART IV – PROTECTION OF WAGES 17. Payment, disposal and recovery of wages, allowances, etc. 18. When wages or salaries due. 19. Deduction of wages. 20. Itemised pay statement. 21. Statement of statutory deductions. 22. Power to amend provisions on pay and statements of deductions. 23. Security bond for wages. 24. Death of an employee. 25. Repayment of remuneration wrongfully withheld or deducted. PART V – RIGHTS AND DUTIES IN EMPLOYMENT 26. Basic minimum conditions of employment. 27. Hours of work. 28. Annual leave. 29. Maternity leave. 30. Sick leave. E7 - 3 [Issue 1] CAP. 226 [Rev. 2012] Employment Section 31. Housing. 32. Water. 33. Food. 34. Medical attention. PART VI – TERMINATION AND DISMISSAL 35. Termination notice. 36. Payment in lieu of notice. 37. Conversion of casual employment to term contract. 38. Waiver of notice by employer. 39. Contract expiring on a journey may be extended. -

Understanding the Tipping Point of Urban Conflict: Violence, Cities and Poverty Reduction in the Developing World

Understanding the tipping point of urban conflict: Violence, cities and poverty reduction in the developing world The case of Patna, India Policy Brief 1.0 Conceptual framework situations where a given social process becomes generalised rather than specific, but Cities are inherently conflictual spaces, in that in a rapid rather than gradual manner. A they concentrate large numbers of diverse tipping point therefore inherently embodies a people with incongruent interests within a dynamic temporal dimension, and can contained environment. This conflict is more moreover apply to both increases as well as often than not managed or resolved in a reductions in violence; we denote a process peaceful manner through a range of social, whereby situations of generalised violence cultural and political mechanisms, but move back to circumstances of managed sometimes can generate violence when such conflict as representing a “reversal” of the forms of regulation break down or can no 1 tipping point of urban conflict. longer cope. The broader development literature on urban violence suggests that it is 1.2 Patna as a case study a phenomenon that can be linked to the Patna was chosen as a case study city due to presence of certain specific factors, or its dual association with poverty and urban combination of factors in cities. In particular, violence. The city has long ranked amongst rapid urban growth, high levels of persistent the poorest Tier II urban settlements (i.e. poverty in cities, youth bulges, political between 1-5 million inhabitants) in India, and exclusion, and gender-based insecurity have is located within the state of Bihar that has all been widely correlated with urban violence historically systematically displayed the lowest in recent years. -

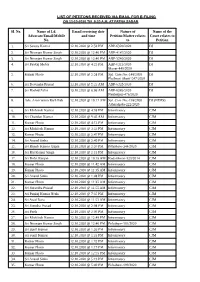

LIST of PETITONS RECEIVED VIA EMAIL for E-FILING Sl. No. Name

LIST OF PETITONS RECEIVED VIA EMAIL FOR E-FILING ON 13-10-2020 Till 9:30 A.M. AT PATNA SADAR Sl. No. Name of Ld. Email receiving date Nature of Name of the Advocate/Email/Mobile and time Petition/Matter relates Court relates to No. to Petition 1. Sri Sanjay Kumar 12.10.2020 @ 2:50 PM ABP-6320/2020 DJ 2. Sri Niranjan Kumar Singh 12.10.2020 @ 12:46 PM ABP-4187/2020 DJ 3. Sri Niranjan Kumar Singh 12.10.2020 @ 12:46 PM ABP-5240/2020 DJ 4. Sri Pankaj Mehta 12.10.2020 @ 4:23 PM ABP-6313/2020 DJ Maner-440/2020 5. Kumar Photo 12.10.2020 @ 5:58 PM Spl. Case No.-148/2020 DJ Phulwari Sharif-547/2020 6. Sri Devendra Prasad 13.10.2020 @ 5:22 AM ABP-6235/2020 DJ 7. Sri Rashid Zafar 13.10.2020 @ 6:06 AM ABP-6385/2020 DJ Naubatpur-476/2020 8. Adv. Association Barh Bab 12.10.2020 @ 10:17 AM Spl. Case No.-138/2020 DJ (NDPS) Athmalgola-222/2020 9. Sri Mithilesh Kumar 12.10.2020 @ 4:38 PM Informatory CJM 10. Sri Chandan Kumar 12.10.2020 @ 9:45 AM Informatory CJM 11. Kumar Photo 12.10.2020 @ 4:13 PM Informatory CJM 12. Sri Mithilesh Kumar 12.10.2020 @ 3:32 PM Informatory CJM 13. Kumar Photo 12.10.2020 @ 2:47 PM Informatory CJM 14. Sri Anand Sinha 12.10.2020 @ 2:40 PM Informatory CJM 15. Sri Rajesh Kumar Gupta 12.10.2020 @ 2:36 PM Pribahore-344/2020 CJM 16. -

Bihar Police Constable

Bihar Police Constable Online Form 2020 Central Selection Board of Constable CSBC Bihar Police Constable Recruitment 2020 Total 8415 Post Important Dates: Bihar Police Constable Form Start Date 13 November 2020 Bihar Consta ble 2020 Last Date 14 December 2020 CSBC Bihar Police Constable Last Date Payment 14 December 2020 Application Fees: • General / OBC / Other State : Rs. 450/- • SC / ST: Rs. 112/- Age Limit: • Age Calculate on 01 August 2020 • Minimum 18 Years & Maximum 25 Years Eligibility: • Intermediate in Any Stream from Any Recognized Board Vacancy Details: General EWS OBC EOBC OBC-Female SC ST Total 3489 842 980 1470 245 1307 82 8415 District Wise Vacancy Details: District Name Total Post District Name Total Post Patna 600 Madhubandi 40 Bhojpur 260 Saharsa 40 Kaimur 80 Madhepura 70 Aurangabad 100 Kishanganj 20 Jahanabad 80 Arriya 20 Muzaffarpur 400 Baka 250 Shivhar 20 Khagadiya 130 Betiyan 80 Begusarai 130 Saran 160 Lakhisarai 150 Gopalganj 100 Rail Patna 100 Bihar Military Police 01 Patna 248 Rail Katihar 100 B.R.O.S.B Patna 1206 Military Police Central Region 07 Central Area Patna 06 Horseman Military Police Ara 52 Tirhut Area, Muzaffapur 07 S.O.I.R.B. Bodhgaya 208 Punia Area 05 Magadh Area Gaya 05 Koshi Area Saharsha 15 Mithila Area Darbanga 09 Eastern Area Bhagalpur 14 Shahabad Area Dehari 02 Munger Area 08 Champaran Area Betiyan 12 Traffic Police H.Q. Patna 16 Begularsarai Area 06 Training H.Q. Patna 44 Bihar Police H.Q. Patna 90 Caste Department, Patna 40 Finance H.Q. Patna 20 State Other Backward Prosecution 44 Special Branch, Patna 468 Bureau Nalanda 240 Economic Offenses U nit , Patna 216 Rohtas 90 Supaul 70 Gaya 200 Purnia 230 Newada 250 Katihar 90 Arwal 06 Bhagalpur 90 Vaishali 150 Navgachiya 70 Sitamarhi 190 Munger 200 Motihari 80 Sekhpura 20 Siwan 100 Jamui 300 Darbangha 170 Rail Muzaffarpur 40 Samastipur 140 Military Police H.Q. -

Multi-Tiered Marriage: Ideas and Influences from New York and Louisiana to the International Community

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by bepress Legal Repository MULTI-TIERED MARRIAGE: IDEAS AND INFLUENCES FROM NEW YORK AND LOUISIANA TO THE INTERNATIONAL COMMUNITY Joel A. Nichols* ABSTRACT This Article contends that American society needs to hold a genuine discussion about alternatives to current conceptions of marriage and family law jurisdiction. Specifically, the Article suggests that the civil government should consider ceding some of its jurisdictional authority over marriage and divorce law to religious communities that are competent and capable of adjudicating the marital rites and rights of their respective adherents. There is historical precedent and preliminary movement toward this end -- both within and without the United States -- which might serve as the framework for further discussions. Within the United States, the relatively new covenant marriage statutes of Louisiana, Arizona, and Arkansas provide a form of two-tiered marriage and divorce law. But there is even an earlier, and potentially more fulsome, example in New York’s get statutes. New York’s laws derive from civil statutes that deal with specific problems raised by the intersection of civil law and Jewish law in marriage and divorce situations. New York’s laws implicitly acknowledge that there are multiple understandings of the marital relationship already present among members of society. These examples from within the United States lay the groundwork for a heartier discussion of the proper role of the state and other groups with respect to marriage and divorce law. As part of that discussion, the Article contends that the United States should look outward, to the practices of other countries. -

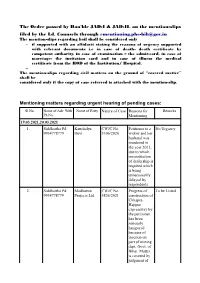

He Order Passed by Hon'ble JAD-I & Hon'ble JAD-II

he Order passed by Hon’ble JAD-I & Hon’ble JAD-II on the mentionslips filed by Ld. Counsels through the e-mail [email protected] In view of the recent surge in the covid cases wherein a large number of Court staffs & officers including some of the Hon'ble Judges of this Court have become Covid- positive and that there has been a sizable cut in the strength of the emplyees for the present, the Ld. Counsels are requested to make mentioning of extremely urgent matters only . The cases already listed before a Bench may be mentioned before the Bench concerned. Since the e-filing portal is now available as such no permission for fresh filing is required, all mention- slips regarding fresh filing are therefore disposed of accordingly. Mentioning matters regarding urgent hearing of pending cases: Name of Adv. Name of Party Nature of Reasons for Remarks Sl.No. With Ph.No. Case Mentioning 03.08.2021 (From 12:00 Noon of 02.08.2021 to 12:00 Noon of 03.08.2021) Civil Matters 1. Devendra Kr. Rani Yadav CWJC No. Withdrawal. To be Listed Mob. No. Not legi- 6365/2020 for withdrawal ble 2. Manoj Kumar Mukund Bihari CWJC For setting aside the No Urgency 9801179773 1188/2021 order dt. 18.01.2020 passed by Respon- dent no. 3 without any base the peti- tioner is suffering from financial prob- lem kindly heard out of turn, but up till now the case has not been listed since long. 3. Alka Verma Kamal Kumar & CWJC IA for addition for No Urgency 9431078283 Ors. -

The Order Passed by Hon'ble JAD-I & JAD-II, on The

The Order passed by Hon'ble JAD-I & JAD-II, on the mention-slips filed by the Ld. Counsels through [email protected] The mention-slips regarding bail shall be considered only – if supported with an affidavit stating the reasons of urgency supported with relevant documents i.e in case of death- death certificate by competent authority, in case of examination – the admit-card, in case of marriage- the invitation card and in case of illness the medical certificate from the HOD of the Institution/ Hospital. – The mention-slips regarding civil matters on the ground of “covered matter” shall be considered only if the copy of case referred is attached with the mention-slip. Mentioning matters regarding urgent hearing of pending cases: Sl.No. Name of Adv. With Name of Party Nature of Case Reasons for Remarks Ph.No. Mentioning 19.03.2021,20.03.2021 1. Siddhartha Pd. Kaushalya CWJC No. Petitioner is a No Urgency 9934778779 Devi 5106/2020 widow and her husband was murdered in the year 2013, due to which reconstitution of dealership is required which is being unnecessarily delayed by respondents. 2. Siddhartha Pd. Madhueon CWJC No. Progress of To be Listed 9934778779 Projects Ltd. 5826/2021 construction of Chhapra- Hajipur expressway by the petitioner has been seriously hampered because of inaction on part of mining dept. Govt. of Bihar. Matter is covered by judgment of Hon'ble Apex Court reported in (2003) 1 SCC 726 Beg Raj Singh Vs. State of UP & Ors. 3. Siddhartha Pd. Upendra MJC No. Tied up matter No Urgency 9934778779 Kishore 765/2021 of Hon'ble Mr. -

Problems in the Criminal Investigation with Reference to Increasing Acquittals: a Study of Criminal Law and Practice in ANDHRA PRADESH

Problems in the criminal investigation with reference to increasing acquittals: A Study of Criminal Law and Practice IN ANDHRA PRADESH Submitted by Dr.K.V.K.Santhy Co-ordinator NALSAR University of Law Justice City, Shameerpet – 500 078 R.R.District, Andhra Pradesh, India Problems in the criminal investigation with reference to increasing acquittals: A Study of Criminal Law and Practice Research Team Project Director : Professor Veer Singh, Vice Chancellor, NALSAR, University of Law Project Coordinator : Dr. KVK Santhy, Assistant Professor, (Criminal Law) NALSAR, University of Law Project Chief Executive : Prof. Madabhushi Sridhar, NALSAR NALSAR, University of Law Researcher : Mr.D.Balakrishna, Asst.Professor of Law NALSAR, University of Law Student Researchers : Ms.Nidhi Malik, BA LLB (Hons.) 5th year Ms.Sruthi Namburi, BA LLB (Hons.) 3rd year Ms.Arushi Garg, BA LLB (Hons.) 3rd year Ms.Shuchita Thapar, BA LLB (Hons.) 3rd year Ms.Harmanpreet Kaur, BA LLB (Hons.) 3rd year Ms.Himabindu Killi, BA LLB (Hons.) 3rd year Ms. Prianca Ravichander, BA LLB (Hons.) 3rd year Ms.Prarthana Vaidya, BA LLB (Hons.) 3rd year Acknowledgements We are greatly indebted to BPRD (Govt. of India) for giving this opportunity to work upon an important and contemporary topic defects in the investigation. We are grateful to Honorable Sri. Justice B.Chandra Kumar, Judge , High Court of Andhra Pradesh, and Honorable Sri. Justice Goda Raghuram, Judge, High Court of Andhra Pradesh for giving us valuable suggestions to improve the system of investigation. We are highly thankful to Dr. Tapan Chakraborthy, Asst Director, BPRD for the constant guidance and encouragement provided to us all through the project. -

Coversheet for Thesis in Sussex Research Online

A University of Sussex DPhil thesis Available online via Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/ This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Please visit Sussex Research Online for more information and further details State Incapacity by Design Unused Grants, Poverty and Electoral Success in Bihar Athakattu Santhosh Mathew A dissertation submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy from the University of Sussex Institute of Development Studies University of Sussex December 2011 ii I hereby declare that this thesis has not been and will not be, submitted in whole or in part to another University for the award of any other degree. Signature: iii UNIVERSITY OF SUSSEX ATHAKATTU SANTHOSH MATHEW DPHIL DEVELOPMENT STUDIES STATE INCAPACITY BY DESIGN Unused Grants, Poverty and Electoral Success in Bihar SUMMARY This thesis offers a perspective on why majority-poor democracies might fail to pursue pro- poor policies. In particular, it discusses why in Bihar, the Rashtriya Janata Dal (RJD) party led by Lalu Prasad Yadav, which claimed to represent the poor and under-privileged, did not claim and spend large amounts of centre–state fiscal transfers that could have reduced poverty, provided employment and benefitted core supporters.