Rob Ninkovich, Linebacker

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ty Law: Why This Pro Football Hall of Famer and Successful Entrepreneur Bets on Himself

SEEKING THE EXTRAORDINARY Ep 3 - Ty Law: Why this Pro Football Hall of Famer and Successful Entrepreneur Bets on Himself FEB 9, 2021 [00:00:00] Michael Nathanson: [00:00:00] Welcome fellow seekers of the extraordinary. Welcome to our shared quest, a quest, not for a thing, but for an ideal, a quest, not for a place, but into the inner unexplored regions of ourselves, a quest to understand how we can achieve our fullest potential by learning from others who have done or are doing exactly that. May we always have the courage and wisdom to learn from those who have something to teach. Join me now in seeking the extraordinary. I’m Michael Nathanson, your chief secret of the extraordinary. Today’s guest is the founder of the high- ly popular Launch trampoline parks, a serial entrepreneur. He’s now an equity owner of V1 vodka, but you may know him better for his 15 years in the NFL. He won three super bowls. As part of the New England Patriots, he was selected for five pro bowls and was a pro bowl MVP. His 53 career interceptions are among the [00:01:00] best in NFL history, making him one of the best cornerbacks of all time. He’s a member of the 2019 class of inductees into the NFL Hall of Fame, joining only 325 other members in this most special achievement, please welcome the extraordinary. Ty Law. Ty, welcome. Ty Law: [00:01:21] Thank you. I like the intro. I liked the intro. -

New England Patriots

NEW ENGLAND PATRIOTS Contact: Stacey James, Director of Media Relations or Anthony Moretti, Asst. Director or Michelle L. Murphy, Media Relations Asst. Gillette Stadium * One Patriot Place * Foxborough, MA 02035 * 508-384-9105 fax: 508-543-9053 [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] For Immediate Release, September 24, 2002 BATTLE OF DIVISION LEADERS – NEW ENGLAND (3-0) TRAVELS TO SAN DIEGO (3-0) MEDIA SCHEDULE This Week: The New England Patriots (3-0) will try to close out the month of September Wednesday, Sept. 25 as only the fifth team in franchise history to begin a campaign with a four-game winning streak when they trek cross-country to face the San Diego Chargers (3-0). The New 10:45-11:15 Head Coach Bill Belichick’s Press England passing attack, which is averaging an NFL-best 316 yards per game, will be Conference (Media Workroom) challenged by the Chargers top rated pass defense. San Diego’s defense leads the NFL, 11:15-11:55 Open Locker Room allowing only 132 passing yards per game and posting 16 sacks. The Patriots currently 12:40-12:55 Photographers Access to Practice hold a 10-game winning streak in the series, their longest against any opponent. The last TBA Chargers Player Conference Call time the Chargers defeated the Patriots was on Nov. 15, 1970. TBA Marty Schottenheimer Conference Call Television: This week’s game will be broadcasted nationally on CBS (locally on WBZ 3:10 Drew Brees National Conference Call Channel 4). The play-by-play duties will be handled by Greg Gumbel, who will be joined in the booth by Phil Simms. -

The Fifth Down

Members get half off on June 2006 Vol. 44, No. 2 Outland book Inside this issue coming in fall The Football Writers Association of President’s Column America is extremely excited about the publication of 60 Years of the Outland, Page 2 which is a compilation of stories on the 59 players who have won the Outland Tro- phy since the award’s inception in 1946. Long-time FWAA member Gene Duf- Tony Barnhart and Dennis fey worked on the book for two years, in- Dodd collect awards terviewing most of the living winners, spin- ning their individual tales and recording Page 3 their thoughts on winning major-college football’s third oldest individual award. The 270-page book is expected to go on-sale this fall online at www.fwaa.com. All-America team checklist Order forms also will be included in the Football Hall of Fame, and 33 are in the 2006-07 FWAA Directory, which will be College Football Hall of Fame. Dr. Outland Pages 4-5 mailed to members in late August. also has been inducted posthumously into As part of the celebration of 60 years the prestigious Hall, raising the number to 34 “Outland Trophy Family members” to of Outland Trophy winners, FWAA mem- bers will be able to purchase the book at be so honored . half the retail price of $25.00. Seven Outland Trophy winners have Nagurski Award watch list Ever since the late Dr. John Outland been No. 1 picks overall in NFL Drafts deeded the award to the FWAA shortly over the years, while others have domi- Page 6 before his death, the Outland Trophy has nated college football and pursued greater honored the best interior linemen in col- heights in other areas upon graduation. -

Illinois ... Football Guide

796.33263 lie LL991 f CENTRAL CIRCULATION '- BOOKSTACKS r '.- - »L:sL.^i;:f j:^:i:j r The person charging this material is re- sponsible for its return to the library from which it was borrowed on or before the Latest Date stamped below. Theft, mutllotlen, UNIVERSITY and undarllnlnfl of books are reasons OF for disciplinary action and may result In dismissal from ILUNOIS UBRARY the University. TO RENEW CAll TEUPHONE CENTEK, 333-8400 AT URBANA04AMPAIGN UNIVERSITY OF ILtlNOIS LIBRARY AT URBANA-CHAMPAIGN APPL LiFr: STU0i£3 JAN 1 9 \m^ , USRARy U. OF 1. URBANA-CHAMPAIGN CONTENTS 2 Division of Intercollegiate 85 University of Michigan Traditions Athletics Directory 86 Michigan State University 158 The Big Ten Conference 87 AU-Time Record vs. Opponents 159 The First Season The University of Illinois 88 Opponents Directory 160 Homecoming 4 The Uni\'ersity at a Glance 161 The Marching Illini 6 President and Chancellor 1990 in Reveiw 162 Chief llliniwek 7 Board of Trustees 90 1990 lUinois Stats 8 Academics 93 1990 Game-by-Game Starters Athletes Behind the Traditions 94 1990 Big Ten Stats 164 All-Time Letterwinners The Division of 97 1990 Season in Review 176 Retired Numbers intercollegiate Athletics 1 09 1 990 Football Award Winners 178 Illinois' All-Century Team 12 DIA History 1 80 College Football Hall of Fame 13 DIA Staff The Record Book 183 Illinois' Consensus All-Americans 18 Head Coach /Director of Athletics 112 Punt Return Records 184 All-Big Ten Players John Mackovic 112 Kickoff Return Records 186 The Silver Football Award 23 Assistant -

African American Head Football Coaches at Division 1 FBS Schools: a Qualitative Study on Turning Points

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2015 African American Head Football Coaches at Division 1 FBS Schools: A Qualitative Study on Turning Points Thaddeus Rivers University of Central Florida Part of the Educational Leadership Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Doctoral Dissertation (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Rivers, Thaddeus, "African American Head Football Coaches at Division 1 FBS Schools: A Qualitative Study on Turning Points" (2015). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 1469. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/1469 AFRICAN AMERICAN HEAD FOOTBALL COACHES AT DIVISION I FBS SCHOOLS: A QUALITATIVE STUDY ON TURNING POINTS by THADDEUS A. RIVERS B.S. University of Florida, 2001 M.A. University of Central Florida, 2008 A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Education in the Department of Child, Family and Community Sciences in the College of Education and Human Performance at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Fall Term 2015 Major Professor: Rosa Cintrón © 2015 Thaddeus A. Rivers ii ABSTRACT This dissertation was centered on how the theory ‘turning points’ explained African American coaches ascension to Head Football Coach at a NCAA Division I FBS school. This work (1) identified traits and characteristics coaches felt they needed in order to become a head coach and (2) described the significant events and people (turning points) in their lives that have influenced their career. -

Miami Dolphins Weekly Release

Miami Dolphins Weekly Release Game 12: Miami Dolphins (4-7) vs. Baltimore Ravens (4-7) Sunday, Dec. 6 • 1 p.m. ET • Sun Life Stadium • Miami Gardens, Fla. RESHAD JONES Tackle total leads all NFL defensive backs and is fourth among all NFL 20 / S 98 defensive players 2 Tied for first in NFL with two interceptions returned for touchdowns Consecutive games with an interception for a touchdown, 2 the only player in team history Only player in the NFL to have at least two interceptions returned 2 for a touchdown and at least two sacks 3 Interceptions, tied for fifth among safeties 7 Passes defensed, tied for sixth-most among NFL safeties JARVIS LANDRY One of two players in NFL to have gained at least 100 yards on rushing (107), 100 receiving (816), kickoff returns (255) and punt returns (252) 14 / WR Catch percentage, fourth-highest among receivers with at least 70 71.7 receptions over the last two years Of two receivers in the NFL to have a special teams touchdown (1 punt return 1 for a touchdown), rushing touchdown (1 rushing touchdown) and a receiving touchdown (4 receiving touchdowns) in 2015 Only player in NFL with a rushing attempt, reception, kickoff return, 1 punt return, a pass completion and a two point conversion in 2015 NDAMUKONG SUH 4 Passes defensed, tied for first among NFL defensive tackles 93 / DT Third-highest rated NFL pass rush interior defensive lineman 91.8 by Pro Football Focus Fourth-highest rated overall NFL interior defensive lineman 92.3 by Pro Football Focus 4 Sacks, tied for sixth among NFL defensive tackles 10 Stuffs, is the most among NFL defensive tackles 4 Pro Bowl selections following the 2010, 2012, 2013 and 2014 seasons TABLE OF CONTENTS GAME INFORMATION 4-5 2015 MIAMI DOLPHINS SEASON SCHEDULE 6-7 MIAMI DOLPHINS 50TH SEASON ALL-TIME TEAM 8-9 2015 NFL RANKINGS 10 2015 DOLPHINS LEADERS AND STATISTICS 11 WHAT TO LOOK FOR IN 2015/WHAT TO LOOK FOR AGAINST THE RAVENS 12 DOLPHINS-RAVENS OFFENSIVE/DEFENSIVE COMPARISON 13 DOLPHINS PLAYERS VS. -

Rams Patriots Rams Offense Rams Defense

New England Patriots vs Los Angeles Rams Sunday, February 03, 2019 at Mercedes-Benz Stadium RAMS RAMS OFFENSE RAMS DEFENSE PATRIOTS No Name Pos WR 83 J.Reynolds 11 K.Hodge DE 90 M.Brockers 94 J.Franklin No Name Pos 4 Zuerlein, Greg K TE 89 T.Higbee 81 G.Everett 82 J.Mundt NT 93 N.Suh 92 T.Smart 69 S.Joseph 2 Hoyer, Brian QB 6 Hekker, Johnny P 3 Gostkowski, Stephen K 11 Hodge, Khadarel WR LT 77 A.Whitworth 70 J.Noteboom DT 99 A.Donald 95 E.Westbrooks 6 Allen, Ryan P 12 Cooks, Brandin WR LG 76 R.Saffold 64 J.Demby WILL 56 D.Fowler 96 M.Longacre 45 O.Okoronkwo 11 Edelman, Julian WR 14 Mannion, Sean QB 12 Brady, Tom QB 16 Goff, Jared QB C 65 J.Sullivan 55 Br.Allen OLB 50 S.Ebukam 53 J.Lawler 49 T.Young 13 Dorsett, Phillip WR 17 Woods, Robert WR RG 66 A.Blythe ILB 58 C.Littleton 54 B.Hager 59 M.Kiser 15 Hogan, Chris WR 19 Natson, JoJo WR 18 Slater, Matt WR 20 Joyner, Lamarcus S RT 79 R.Havenstein ILB 26 M.Barron 52 R.Wilson 21 Harmon, Duron DB 21 Talib, Aqib CB WR 12 B.Cooks 19 J.Natson LCB 22 M.Peters 37 S.Shields 31 D.Williams 22 Melifonwu, Obi DB 22 Peters, Marcus CB 23 Chung, Patrick S 23 Robey, Nickell CB WR 17 R.Woods RCB 21 A.Talib 32 T.Hill 23 N.Robey 24 Gilmore, Stephon CB 24 Countess, Blake DB QB 16 J.Goff 14 S.Mannion SS 43 J.Johnson 24 B.Countess 26 Michel, Sony RB 26 Barron, Mark LB 27 Jackson, J.C. -

2019 Panini Encased Football Checklist

2019 Panini Encased Football HITS Totals By Type 226 Players with HITS (Autos/Relics); 32 players with just base cards Team Total AUTO Only AUTO RELIC RELIC Only A.J. Brown 322 322 A.J. Green 91 91 Aaron Donald 26 26 Aaron Jones 20 20 Aaron Rodgers 21 21 Adam Thielen 237 20 56 161 Adrian Peterson 10 10 Alejandro Villanueva 91 91 Alexander Mattison 561 300 100 161 Allen Robinson II 65 65 Alshon Jeffery 111 111 Alvin Kamara 206 206 Amari Cooper 111 20 91 Andre Reed 101 101 Andrew Luck 41 41 Andy Dalton 45 45 Andy Isabella 561 300 100 161 Antonio Brown Base Only Archie Manning 157 66 91 Baker Mayfield 227 66 161 Barry Sanders 19 19 Ben Roethlisberger 97 5 16 76 Benny Snell Jr. 722 300 100 322 Bo Jackson 34 34 Bobby Wagner Base Only Boomer Esiason 56 56 Bradley Chubb 161 161 Brandin Cooks 10 10 Brett Favre 123 16 16 91 Brian Dawkins 147 56 91 Brian Westbrook 147 56 91 Bruce Smith 56 56 Bryce Love 722 300 100 322 GroupBreakChecklists.com 2019 Panini Encased Football HITS Totals By Type Team Total AUTO Only AUTO RELIC RELIC Only Budda Baker 45 45 Calvin Johnson 91 91 Calvin Ridley 217 56 161 Cam Newton Base Only Cameron Wake 45 45 Carson Wentz 44 10 34 Case Keenum Base Only Champ Bailey 147 56 91 Charles Woodson 107 16 91 Chris Boswell 45 45 Chris Long 91 91 Chris Spielman 56 56 Christian Kirk 161 161 Christian McCaffrey 237 76 161 Christian Okoye 56 56 Clinton Portis 91 91 Cooper Kupp 161 161 Corey Davis 111 111 Curtis Martin 56 56 Dak Prescott Base Only Dalvin Cook 20 20 Damien Harris 722 300 100 322 Dan Fouts 132 41 91 Dan Hampton 16 16 Dan Marino 16 16 Daniel Jones 983 300 200 483 Dante Pettis 161 161 Darius Leonard Base Only Darius Slay Jr. -

Illinois ... Football Guide

University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign !~he Quad s the :enter of :ampus ife 3 . H«H» H 1 i % UI 6 U= tiii L L,._ L-'IA-OHAMPAIGK The 1990 Illinois Football Media Guide • The University of Illinois . • A 100-year Tradition, continued ~> The University at a Glance 118 Chronology 4 President Stanley Ikenberrv • The Athletes . 4 Chancellor Morton Weir 122 Consensus All-American/ 5 UI Board of Trustees All-Big Ten 6 Academics 124 Football Captains/ " Life on Campus Most Valuable Players • The Division of 125 All-Stars Intercollegiate Athletics 127 Academic All-Americans/ 10 A Brief History Academic All-Big Ten 11 Football Facilities 128 Hall of Fame Winners 12 John Mackovic 129 Silver Football Award 10 Assistant Coaches 130 Fighting Illini in the 20 D.I.A. Staff Heisman Voting • 1990 Outlook... 131 Bruce Capel Award 28 Alpha/Numerical Outlook 132 Illini in the NFL 30 1990 Outlook • Statistical Highlights 34 1990 Fighting Illini 134 V early Statistical Leaders • 1990 Opponents at a Glance 136 Individual Records-Offense 64 Opponent Previews 143 Individual Records-Defense All-Time Record vs. Opponents 41 NCAA Records 75 UNIVERSITY LIBRARY 78 UI Travel Plans/ 145 Freshman /Single-Play/ ILLINOIS AT URBANA-CHAMPAIGN Opponent Directory Regular Season UNIVERSITY OF responsible for its charging this material is • A Look back at the 1989 Season Team Records The person on or before theidue date. 146 Ail-Time Marks renewal or return to the library Sll 1989 Illinois Stats for is $125.00, $300.00 14, Top Performances minimum fee for a lost item 82 1989 Big Ten Stats The 149 Television Appearances journals. -

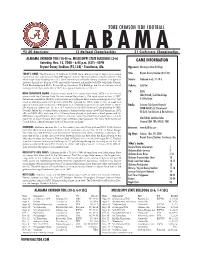

2008 Alabama FB Game Notes

2008 CRIMSON TIDE FOOTBALL 92 All-Americans ALABAMA12 National Championships 21 Conference Championships ALABAMA CRIMSON TIDE (10-0) vs. MISSISSIPPI STATE BULLDOGS (3-6) GAME INFORMATION Saturday, Nov. 15, 2008 - 6:45 p.m. (CST) - ESPN Bryant-Denny Stadium (92,138) - Tuscaloosa, Ala. Opponent: Mississippi State Bulldogs TODAY’S GAME: The University of Alabama football team returns home to begin a two-game Site: Bryant-Denny Stadium (92,138) homestand that will close out the 2008 regular season. The top-ranked Crimson Tide host the Mississippi State Bulldogs in a SEC West showdown at Bryant-Denny Stadium. The game is Series: Alabama leads, 71-18-3 slated to kickoff at 6:45 p.m. (CST) and will be televised nationally by ESPN with Mike Patrick, Todd Blackledge and Holly Rowe calling the action. The Bulldogs are 3-6 on the season and Tickets: Sold Out coming off of a bye week after a 14-13 loss against Kentucky on Nov. 1. TV: ESPN HEAD COACH NICK SABAN: Alabama head coach Nick Saban (Kent State, 1973) is in his second season with the Crimson Tide. He was named the school’s 27th head coach on Jan. 3, 2007. Mike Patrick, Todd Blackledge Saban has compiled a 108-48-1 (.691) record as a collegiate head coach, including an 17-6 (.739) & Holly Rowe mark at Alabama and a 10-0 record in 2008. He captured his 100th career victory in week two against Tulane and coached his 150th game as a collegiate head coach in week three vs. West- Radio: Crimson Tide Sports Network ern Kentucky. -

New York Jets Vs. New England Patriots

No. Name Pos. No. Name Pos. 3 David Fales QB 2 Mike Nugent K 4 Lachlan Edwards P 4 Jarrett Stidham QB 9 Sam Ficken K NEW YORK JETS VS. NEW ENGLAND PATRIOTS 7 Jake Bailey P 10 Braxton Berrios WR 10 Josh Gordon WR 11 Robby Anderson WR 11 Julian Edelman WR 14 Sam Darnold QB 12 Tom Brady QB 15 Josh Bellamy WR MONDAY, OCTOBER 21, 2019 • NEWYORKJETS.COM • @NYJETS • @NYJETSPR 13 Phillip Dorsett II WR 17 Vyncint Smith WR 16 Jakobi Meyers WR 18 Demaryius Thomas WR JETS OFFENSE JETS DEFENSE 18 Matthew Slater WR 20 Marcus Maye S 21 Duron Harmon DB WR 11 Robby Anderson 17 Vyncint Smith DL 92 Leonard Williams 94 Folorunso Fatukasi 60 Jordan Willisi 21 Nate Hairston CB 23 Patrick Chung S 22 Trumaine Johnson CB LT 68 Kelvin Beachum 69 Conor McDermott DL 99 Steve McLendon 95 Quinnen Williams 24 Stephon Gilmore CB 25 Trenton Cannon RB LG 70 Kelechi Osemele 71 Alex Lewis DL 96 Henry Anderson 98 Kyle Phillips 25 Terrence Brooks DB 26 Le’Veon Bell RB C 55 Ryan Kalil 78 Jonotthan Harrison OLB 48 Jordan Jenkins 93 Tarell Basham 26 Sony Michel RB 27 Darryl Roberts CB RG 67 Brian Winters 77 Tom Compton ILB 57 C.J. Mosley 47 Albert McClellan 27 J.C. Jackson DB 29 Bilal Powell RB RT 75 Chuma Edoga 72 Brandon Shell ILB 46 Neville Hewitt 53 Blake Cashman 28 James White RB 32 Blake Countess S 30 Jason McCourty CB TE 89 Chris Herndon 84 Ryan Griffin 87 Daniel Brown OLB 51 Brandon Copeland 44 Harvey Langi 33 Jamal Adams S 31 Jonathan Jones DB 34 Brian Poole CB 85 Trevon Wesco CB 22 Trumaine Johnson 21 Nate Hairston 32 Devin McCourty DB 41 Matthias Farley S WR 82 Jamison -

Broncos Defense Broncos Offense Broncos

65605_Broncos 9-24-06 9/21/06 4:41 PM Page 1 NEW ENGLAND New England Patriots (2 - 0) vs. Denver Broncos (1 - 1) DENVER # NAME ..................POS Sunday, September 24, 2006 ★ 8:15 p.m. ★ Gillette Stadium # NAME ..................POS 3 Stephen Gostkowski ..K 1 Jason Elam................K 8 Josh Miller ................P 3 Paul Ernster............P/K 12 Tom Brady ..............QB PATRIOTS OFFENSE PATRIOTS DEFENSE 6 Jay Cutler ..............QB 16 Matt Cassel ............QB 11 Quincy Morgan ......WR WR: 87 Reche Caldwell 85 Doug Gabriel LE: 94 Ty Warren 99 Mike Wright 91 Marquise Hill 17 Chad Jackson ........WR 14 Todd Devoe............WR 21 Randall Gay ............CB LT: 72 Matt Light 65 Wesley Britt NT: 75 Vince Wilfork 96 Johnathan Sullivan* 90 Le Kevin Smith* 15 Brandon Marshall....WR 22 Asante Samuel ........CB LG: 70 Logan Mankins 64 Gene Mruczkowski* RE: 93 Richard Seymour 97 Jarvis Green 16 Jake Plummer ........QB 23 Willie Andrews ........DB C: 67 Dan Koppen 71 Russ Hochstein OLB: 59 Rosevelt Colvin 58 Pierre Woods* 20 Mike Bell ................RB 25 Artrell Hawkins ........DB RG: 61 Stephen Neal 71 Russ Hochstein ILB: 54 Tedy Bruschi 53 Larry Izzo 52 Eric Alexander 21 Hamza Abdullah ........S 26 Eugene Wilson ........DB RT: 68 Ryan O'Callaghan 77 Nick Kaczur* 22 Domonique Foxworth..CB ILB: 55 Junior Seau 51 Don Davis 27 Ellis Hobbs ..............CB TE: 84 Benjamin Watson 45 Garrett Mills* 24 Champ Bailey ..........CB OLB: 50 Mike Vrabel 95 Tully Banta-Cain 28 Corey Dillon ............RB TE: 82 Daniel Graham 86 David Thomas 25 Nick