Dodecatheon Pulchellum

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

"National List of Vascular Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands: 1996 National Summary."

Intro 1996 National List of Vascular Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands The Fish and Wildlife Service has prepared a National List of Vascular Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands: 1996 National Summary (1996 National List). The 1996 National List is a draft revision of the National List of Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands: 1988 National Summary (Reed 1988) (1988 National List). The 1996 National List is provided to encourage additional public review and comments on the draft regional wetland indicator assignments. The 1996 National List reflects a significant amount of new information that has become available since 1988 on the wetland affinity of vascular plants. This new information has resulted from the extensive use of the 1988 National List in the field by individuals involved in wetland and other resource inventories, wetland identification and delineation, and wetland research. Interim Regional Interagency Review Panel (Regional Panel) changes in indicator status as well as additions and deletions to the 1988 National List were documented in Regional supplements. The National List was originally developed as an appendix to the Classification of Wetlands and Deepwater Habitats of the United States (Cowardin et al.1979) to aid in the consistent application of this classification system for wetlands in the field.. The 1996 National List also was developed to aid in determining the presence of hydrophytic vegetation in the Clean Water Act Section 404 wetland regulatory program and in the implementation of the swampbuster provisions of the Food Security Act. While not required by law or regulation, the Fish and Wildlife Service is making the 1996 National List available for review and comment. -

Super Cyclamen a Full Line-Up!

Cyclamen by Size MICRO MINI INTERMEDIATE STANDARD JUMBO Micro Verano Rembrandt XL Mammoth Mini Winter Allure Picasso Super Cyclamen A Full Line-up! Seed of the cyclamen series listed in this brochure are available through Sakata for shipment effective January 2015. In addition, the following series are available via drop ship directly from The Netherlands. Please contact Sakata or your preferred dealer for more information. Sakata Ornamentals Carino I mini Original I standard P.O. Box 880 Compact I mini Macro I standard Morgan Hill, CA 95038 DaVinci I mini Petticoat I mini 408.778.7758 Michelangelo I mini Merengue I intermediate www.sakataornamentals.com Jive I mini 10.2014 Super Cyclamen A Full Line-up! Sakata Seed America is proud to offer a complete line of innovative cyclamen series bred by the leading cyclamen experts at Schoneveld Breeding. From mini to jumbo, we’re delivering quality you can count on… Uniformity Rounded plant habit Central blooming Thick flower stems Abundant buds & blooms Long shelf life Enjoy! Our full line-up of cyclamen delivers long-lasting beauty indoors and out. Micro Verano F1 Cyclamen Micro I P F1 Cyclamen Mini I B P • Genetically compact Dark Salmon Pink Dark Violet Deep Dark Violet • More tolerant of higher temperatures • Perfect for 2-inch pot production • Well-known for fast and very uniform flowering • A great item for special marketing programs • Excellent for landscape use MINIMUM GERM: 85% MINIMUM GERM: 85% SEED FORM: Raw SEED FORM: Raw TOTAL CROP TIME: 27 – 28 Weeks TOTAL CROP TIME: 25 – 27 Weeks -

Rare Vascular Plant Surveys in the Polletts Cove and Lahave River Areas of Nova Scotia

Rare Vascular Plant Surveys in the Polletts Cove and LaHave River areas of Nova Scotia David Mazerolle, Sean Blaney and Alain Belliveau Atlantic Canada Conservation Data Centre November 2014 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This project was funded by the Nova Scotia Department of Natural Resources, through their Species at Risk Conservation Fund. The Atlantic Canada Conservation Data Centre appreciates the opportunity provided by the fund to have visited these botanically significant areas. We also thank Sean Basquill for mapping, fieldwork and good company on our Polletts Cove trip, and Cape Breton Highlands National Park for assistance with vehicle transportation at the start of that trip. PHOTOGRAPHY CREDITS All photographs included in this report were taken by the authors. 1 INTRODUCTION This project, funded by the Nova Scotia Species at Risk Conservation Fund, focused on two areas of high potential for rare plant occurrence: 1) the Polletts Cove and Blair River system in northern Cape Breton, covered over eight AC CDC botanist field days; and 2) the lower, non-tidal 29 km and selected tidal portions of the LaHave River in Lunenburg County, covered over 12 AC CDC botanist field days. The Cape Breton Highlands support a diverse array of provincially rare plants, many with Arctic or western affinity, on cliffs, river shores, and mature deciduous forests in the deep ravines (especially those with more calcareous bedrock and/or soil) and on the peatlands and barrens of the highland plateau. Recent AC CDC fieldwork on Lockhart Brook, Big Southwest Brook and the North Aspy River sites similar to the Polletts Cove and Blair River valley was very successful, documenting 477 records of 52 provincially rare plant species in only five days of fieldwork. -

Outline of Angiosperm Phylogeny

Outline of angiosperm phylogeny: orders, families, and representative genera with emphasis on Oregon native plants Priscilla Spears December 2013 The following listing gives an introduction to the phylogenetic classification of the flowering plants that has emerged in recent decades, and which is based on nucleic acid sequences as well as morphological and developmental data. This listing emphasizes temperate families of the Northern Hemisphere and is meant as an overview with examples of Oregon native plants. It includes many exotic genera that are grown in Oregon as ornamentals plus other plants of interest worldwide. The genera that are Oregon natives are printed in a blue font. Genera that are exotics are shown in black, however genera in blue may also contain non-native species. Names separated by a slash are alternatives or else the nomenclature is in flux. When several genera have the same common name, the names are separated by commas. The order of the family names is from the linear listing of families in the APG III report. For further information, see the references on the last page. Basal Angiosperms (ANITA grade) Amborellales Amborellaceae, sole family, the earliest branch of flowering plants, a shrub native to New Caledonia – Amborella Nymphaeales Hydatellaceae – aquatics from Australasia, previously classified as a grass Cabombaceae (water shield – Brasenia, fanwort – Cabomba) Nymphaeaceae (water lilies – Nymphaea; pond lilies – Nuphar) Austrobaileyales Schisandraceae (wild sarsaparilla, star vine – Schisandra; Japanese -

AGCBC Seedlist2019booklet

! Alpine Garden Club of British Columbia Seed Exchange 2019 Alpine Garden Club of British Columbia Seed Exchange 2019 We are very grateful to all those members who have made our Seed Exchange possible through donating seeds. The number of donors was significantly down this year, which makes the people who do donate even more precious. We particularly want to thank the new members who donated seed in their first year with the Club. A big thank-you also to those living locally who volunteer so much time and effort to packaging and filling orders. READ THE FOLLOWING INSTRUCTIONS CAREFULLY BEFORE FILLING IN THE REQUEST FORM. PLEASE KEEP YOUR SEED LIST, packets will be marked by number only. Return the enclosed request form by mail or, if you have registered to do so, by the on-line form, as soon as possible, but no later than DECEMBER 8. Allocation: Donors may receive up to 60 packets and non-donors 30 packets, limit of one packet of each selection. Donors receive preference for seeds in short supply (USDA will permit no more than 50 packets for those living in the USA). List first choices by number only, in strict numerical order, from left to right on the order form. Enter a sufficient number of second choices in the spaces below, since we may not be able to provide all your first choices. Please print clearly. Please be aware that we have again listed wild collected seed (W) and garden seed (G) of the same species separately, which is more convenient for people ordering on-line. -

December 2012 Number 1

Calochortiana December 2012 Number 1 December 2012 Number 1 CONTENTS Proceedings of the Fifth South- western Rare and Endangered Plant Conference Calochortiana, a new publication of the Utah Native Plant Society . 3 The Fifth Southwestern Rare and En- dangered Plant Conference, Salt Lake City, Utah, March 2009 . 3 Abstracts of presentations and posters not submitted for the proceedings . 4 Southwestern cienegas: Rare habitats for endangered wetland plants. Robert Sivinski . 17 A new look at ranking plant rarity for conservation purposes, with an em- phasis on the flora of the American Southwest. John R. Spence . 25 The contribution of Cedar Breaks Na- tional Monument to the conservation of vascular plant diversity in Utah. Walter Fertig and Douglas N. Rey- nolds . 35 Studying the seed bank dynamics of rare plants. Susan Meyer . 46 East meets west: Rare desert Alliums in Arizona. John L. Anderson . 56 Calochortus nuttallii (Sego lily), Spatial patterns of endemic plant spe- state flower of Utah. By Kaye cies of the Colorado Plateau. Crystal Thorne. Krause . 63 Continued on page 2 Copyright 2012 Utah Native Plant Society. All Rights Reserved. Utah Native Plant Society Utah Native Plant Society, PO Box 520041, Salt Lake Copyright 2012 Utah Native Plant Society. All Rights City, Utah, 84152-0041. www.unps.org Reserved. Calochortiana is a publication of the Utah Native Plant Society, a 501(c)(3) not-for-profit organi- Editor: Walter Fertig ([email protected]), zation dedicated to conserving and promoting steward- Editorial Committee: Walter Fertig, Mindy Wheeler, ship of our native plants. Leila Shultz, and Susan Meyer CONTENTS, continued Biogeography of rare plants of the Ash Meadows National Wildlife Refuge, Nevada. -

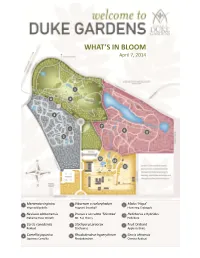

What's in Bloom

WHAT’S IN BLOOM April 7, 2014 5 4 6 2 7 1 9 8 3 12 10 11 1 Mertensia virginica 5 Viburnum x carlcephalum 9 Malus ‘Hopa’ Virginia Bluebells Fragrant Snowball Flowering Crabapple 2 Neviusia alabamensis 6 Prunus x serrulata ‘Shirotae’ 10 Helleborus x hybridus Alabama Snow Wreath Mt. Fuji Cherry Hellebore 3 Cercis canadensis 7 Stachyurus praecox 11 Fruit Orchard Redbud Stachyurus Apple cultivars 4 Camellia japonica 8 Rhododendron hyperythrum 12 Cercis chinensis Japanese Camellia Rhododendron Chinese Redbud WHAT’S IN BLOOM April 7, 2014 BLOMQUIST GARDEN OF NATIVE PLANTS Amelanchier arborea Common Serviceberry Sanguinaria canadensis Bloodroot Cornus florida Flowering Dogwood Stylophorum diphyllum Celandine Poppy Thalictrum thalictroides Rue Anemone Fothergilla major Fothergilla Trillium decipiens Chattahoochee River Trillium Hepatica nobilis Hepatica Trillium grandiflorum White Trillium Hexastylis virginica Wild Ginger Hexastylis minor Wild Ginger Trillium pusillum Dwarf Wakerobin Illicium floridanum Florida Anise Tree Trillium stamineum Blue Ridge Wakerobin Malus coronaria Sweet Crabapple Uvularia sessilifolia Sessileleaf Bellwort Mertensia virginica Virginia Bluebells Pachysandra procumbens Allegheny spurge Prunus americana American Plum DORIS DUKE CENTER GARDENS Camellia japonica Japanese Camellia Pulmonaria ‘Diana Clare’ Lungwort Cercis canadensis Redbud Prunus persica Flowering Peach Puschkinia scilloides Striped Squill Cercis chinensis Redbud Sanguinaria canadensis Bloodroot Clematis armandii Evergreen Clematis Spiraea prunifolia Bridalwreath -

These De Doctorat De L'universite Paris-Saclay

NNT : 2016SACLS250 THESE DE DOCTORAT DE L’UNIVERSITE PARIS-SACLAY, préparée à l’Université Paris-Sud ÉCOLE DOCTORALE N° 567 Sciences du Végétal : du Gène à l’Ecosystème Spécialité de doctorat (Biologie) Par Mlle Nour Abdel Samad Titre de la thèse (CARACTERISATION GENETIQUE DU GENRE IRIS EVOLUANT DANS LA MEDITERRANEE ORIENTALE) Thèse présentée et soutenue à « Beyrouth », le « 21/09/2016 » : Composition du Jury : M., Tohmé, Georges CNRS (Liban) Président Mme, Garnatje, Teresa Institut Botànic de Barcelona (Espagne) Rapporteur M., Bacchetta, Gianluigi Università degli Studi di Cagliari (Italie) Rapporteur Mme, Nadot, Sophie Université Paris-Sud (France) Examinateur Mlle, El Chamy, Laure Université Saint-Joseph (Liban) Examinateur Mme, Siljak-Yakovlev, Sonja Université Paris-Sud (France) Directeur de thèse Mme, Bou Dagher-Kharrat, Magda Université Saint-Joseph (Liban) Co-directeur de thèse UNIVERSITE SAINT-JOSEPH FACULTE DES SCIENCES THESE DE DOCTORAT DISCIPLINE : Sciences de la vie SPÉCIALITÉ : Biologie de la conservation Sujet de la thèse : Caractérisation génétique du genre Iris évoluant dans la Méditerranée Orientale. Présentée par : Nour ABDEL SAMAD Pour obtenir le grade de DOCTEUR ÈS SCIENCES Soutenue le 21/09/2016 Devant le jury composé de : Dr. Georges TOHME Président Dr. Teresa GARNATJE Rapporteur Dr. Gianluigi BACCHETTA Rapporteur Dr. Sophie NADOT Examinateur Dr. Laure EL CHAMY Examinateur Dr. Sonja SILJAK-YAKOVLEV Directeur de thèse Dr. Magda BOU DAGHER KHARRAT Directeur de thèse Titre : Caractérisation Génétique du Genre Iris évoluant dans la Méditerranée Orientale. Mots clés : Iris, Oncocyclus, région Est-Méditerranéenne, relations phylogénétiques, status taxonomique. Résumé : Le genre Iris appartient à la famille des L’approche scientifique est basée sur de nombreux Iridacées, il comprend plus de 280 espèces distribuées outils moléculaires et génétiques tels que : l’analyse de à travers l’hémisphère Nord. -

National Wetlands Inventory Map Report for Quinault Indian Nation

National Wetlands Inventory Map Report for Quinault Indian Nation Project ID(s): R01Y19P01: Quinault Indian Nation, fiscal year 2019 Project area The project area (Figure 1) is restricted to the Quinault Indian Nation, bounded by Grays Harbor Co. Jefferson Co. and the Olympic National Park. Appendix A: USGS 7.5-minute Quadrangles: Queets, Salmon River West, Salmon River East, Matheny Ridge, Tunnel Island, O’Took Prairie, Thimble Mountain, Lake Quinault West, Lake Quinault East, Taholah, Shale Slough, Macafee Hill, Stevens Creek, Moclips, Carlisle. • < 0. Figure 1. QIN NWI+ 2019 project area (red outline). Source Imagery: Citation: For all quads listed above: See Appendix A Citation Information: Originator: USDA-FSA-APFO Aerial Photography Field Office Publication Date: 2017 Publication place: Salt Lake City, Utah Title: Digital Orthoimagery Series of Washington Geospatial_Data_Presentation_Form: raster digital data Other_Citation_Details: 1-meter and 1-foot, Natural Color and NIR-False Color Collateral Data: . USGS 1:24,000 topographic quadrangles . USGS – NHD – National Hydrography Dataset . USGS Topographic maps, 2013 . QIN LiDAR DEM (3 meter) and synthetic stream layer, 2015 . Previous National Wetlands Inventories for the project area . Soil Surveys, All Hydric Soils: Weyerhaeuser soil survey 1976, NRCS soil survey 2013 . QIN WET tables, field photos, and site descriptions, 2016 to 2019, Janice Martin, and Greg Eide Inventory Method: Wetland identification and interpretation was done “heads-up” using ArcMap versions 10.6.1. US Fish & Wildlife Service (USFWS) National Wetlands Inventory (NWI) mapping contractors in Portland, Oregon completed the original aerial photo interpretation and wetland mapping. Primary authors: Nicholas Jones of SWCA Environmental Consulting. 100% Quality Control (QC) during the NWI mapping was provided by Michael Holscher of SWCA Environmental Consulting. -

National List of Vascular Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands 1996

National List of Vascular Plant Species that Occur in Wetlands: 1996 National Summary Indicator by Region and Subregion Scientific Name/ North North Central South Inter- National Subregion Northeast Southeast Central Plains Plains Plains Southwest mountain Northwest California Alaska Caribbean Hawaii Indicator Range Abies amabilis (Dougl. ex Loud.) Dougl. ex Forbes FACU FACU UPL UPL,FACU Abies balsamea (L.) P. Mill. FAC FACW FAC,FACW Abies concolor (Gord. & Glend.) Lindl. ex Hildebr. NI NI NI NI NI UPL UPL Abies fraseri (Pursh) Poir. FACU FACU FACU Abies grandis (Dougl. ex D. Don) Lindl. FACU-* NI FACU-* Abies lasiocarpa (Hook.) Nutt. NI NI FACU+ FACU- FACU FAC UPL UPL,FAC Abies magnifica A. Murr. NI UPL NI FACU UPL,FACU Abildgaardia ovata (Burm. f.) Kral FACW+ FAC+ FAC+,FACW+ Abutilon theophrasti Medik. UPL FACU- FACU- UPL UPL UPL UPL UPL NI NI UPL,FACU- Acacia choriophylla Benth. FAC* FAC* Acacia farnesiana (L.) Willd. FACU NI NI* NI NI FACU Acacia greggii Gray UPL UPL FACU FACU UPL,FACU Acacia macracantha Humb. & Bonpl. ex Willd. NI FAC FAC Acacia minuta ssp. minuta (M.E. Jones) Beauchamp FACU FACU Acaena exigua Gray OBL OBL Acalypha bisetosa Bertol. ex Spreng. FACW FACW Acalypha virginica L. FACU- FACU- FAC- FACU- FACU- FACU* FACU-,FAC- Acalypha virginica var. rhomboidea (Raf.) Cooperrider FACU- FAC- FACU FACU- FACU- FACU* FACU-,FAC- Acanthocereus tetragonus (L.) Humm. FAC* NI NI FAC* Acanthomintha ilicifolia (Gray) Gray FAC* FAC* Acanthus ebracteatus Vahl OBL OBL Acer circinatum Pursh FAC- FAC NI FAC-,FAC Acer glabrum Torr. FAC FAC FAC FACU FACU* FAC FACU FACU*,FAC Acer grandidentatum Nutt. -

(Dr. Sc. Nat.) Vorgelegt Der Mathematisch-Naturwissenschaftl

Zurich Open Repository and Archive University of Zurich Main Library Strickhofstrasse 39 CH-8057 Zurich www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 2012 Flowers, sex, and diversity: Reproductive-ecological and macro-evolutionary aspects of floral variation in the Primrose family, Primulaceae de Vos, Jurriaan Michiel Posted at the Zurich Open Repository and Archive, University of Zurich ZORA URL: https://doi.org/10.5167/uzh-88785 Dissertation Originally published at: de Vos, Jurriaan Michiel. Flowers, sex, and diversity: Reproductive-ecological and macro-evolutionary aspects of floral variation in the Primrose family, Primulaceae. 2012, University of Zurich, Facultyof Science. FLOWERS, SEX, AND DIVERSITY. REPRODUCTIVE-ECOLOGICAL AND MACRO-EVOLUTIONARY ASPECTS OF FLORAL VARIATION IN THE PRIMROSE FAMILY, PRIMULACEAE Dissertation zur Erlangung der naturwissenschaftlichen Doktorwürde (Dr. sc. nat.) vorgelegt der Mathematisch-naturwissenschaftliche Fakultät der Universität Zürich von Jurriaan Michiel de Vos aus den Niederlanden Promotionskomitee Prof. Dr. Elena Conti (Vorsitz) Prof. Dr. Antony B. Wilson Dr. Colin E. Hughes Zürich, 2013 !!"#$"#%! "#$%&$%'! (! )*'+,,&$-+''*$.! /! '0$#1'2'! 3! "4+1%&5!26!!"#"$%&'(#)$*+,-)(*#! 77! "4+1%&5!226!-*#)$%.)(#!'&*#!/'%#+'.0*$)/)"$1'(12%-).'*3'0")"$*.)4&4'*#' "5*&,)(*#%$4'+(5"$.(3(-%)(*#'$%)".'(#'+%$6(#7.'2$(1$*.".! 89! "4+1%&5!2226!.1%&&'%#+',!&48'%'9,%#)()%)(5":'-*12%$%)(5"'"5%&,%)(*#'*3' )0"';."&3(#!'.4#+$*1"<'(#'0")"$*.)4&*,.'%#+'0*1*.)4&*,.'2$(1$*.".! 93! "4+1%&5!2:6!$"2$*+,-)(5"'(12&(-%)(*#.'*3'0"$=*!%14'(#'0*1*.)4&*,.' 2$(1$*.".>'5%$(%)(*#'+,$(#!'%#)0".(.'%#+'$"2$*+,-)(5"'%..,$%#-"'(#' %&2(#"'"#5($*#1"#).! 7;7! "4+1%&5!:6!204&*!"#")(-'%#%&4.(.'*3'!"#$%&''."-)(*#'!"#$%&''$"5"%&.' $%12%#)'#*#/1*#*204&4'%1*#!'1*2$0*&*!(-%&&4'+(.)(#-)'.2"-(".! 773! "4+1%&5!:26!-*#-&,+(#!'$"1%$=.! 7<(! +"=$#>?&@.&,&$%'! 7<9! "*552"*?*,!:2%+&! 7<3! !!"#$$%&'#""!&(! Es ist ein zentrales Ziel in der Evolutionsbiologie, die Muster der Vielfalt und die Prozesse, die sie erzeugen, zu verstehen. -

DAVIDSONIA VOLUME 6 NUMBER 1 Spring 1975 Cover

DAVIDSONIA VOLUME 6 NUMBER 1 Spring 1975 Cover Cyclamen orbiculatum var. coum, a member of the Primrose Family (Primulaceae). This hardy and easily grown plant forms attractive clumps when naturalized in the garden. Magnolia X soulangeana, the Saucer Magnolia DAVIDSONIA VOLUME 6 NUMBER 1 Spring 1975 Davidsonia is published quarterly by The Botanical Garden of The University of British Columbia, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada V6T 1W5. Annual subscription, six dollars. Single numbers, one dollar and fifty cents. All editorial matters or information concerning subscriptions should be addressed to The Director of The Botanical Garden. Acknowledgements Pen and ink illustrations are by Mrs. Lesley Bohm. Photographs accompanying the feature article are by Dr. C. J. Marchant; the map showing cliff erosion sites was prepared by Miss Andrea Adamovich. The article on Dodecatheon was researched by Mrs. Sylvia Taylor and Ms. Geraldine Guppy. Editorial and layout assistance was provided by Ms. Geraldine Guppy and Mrs. Jean Marchant. Cliff Erosion Control with Plants CHRISTOPHER J. MARCHANT For at least half a century, perhaps several centuries, the 300 foot high sea cliffs at Point Grey have been gradually eroding. Aerial photographs indicate this, and they also show that in recent years an increasing area has been affected. It appears that there has always been a somewhat cyclical variation in the vegetation cover, which has advanced and receded coincident with fluctuation in cliff stability. However, this natural geological phenomenon has now become a major cause for concern to the University of British Columbia, since parts of the university campus sit strategically on the summit of the cliffs, and some of the land and large buildings (among them the temporary headquarters of the Botanical Garden) may be threatened with eventual subsidence into the ocean.