Alternative Formats If You Require This Document in an Alternative Format, Please Contact: [email protected]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Baseline for Democracy and Governance Project, Search For

Baseline for Democracy and Governance Project Search for Common Ground Background Over the next three-year period, Sierra Leone must capitalize on the opportunities provided by the end of the civil conflict to ensure a peaceful transition into a long-term development phase. These opportunities include: • the discourse of public participation and dialogue • tolerance for openness and freedom of the press • implementation of a decentralization policy and structural reforms. Media tolerance and diversification is central to a wider and broader range of available public information. A viable and functioning public information network supports deeper analysis on issues and the mobilization of the population for engagement in governance processes, including local and national elections, anti-corruption initiatives, and budgetary monitoring, among others. Search for Common Ground in Sierra Leone (SFCG) with the support of the United States Agency for International Development through cooperative agreement 636-A-00-05-00040 is supporting these transformation processes over the next three to five years. Capitalizing on new entry points created by governance reform and decentralization, SFCG, using its trusted media tools integrated with community outreach, will support the creation of demand for good governance and accountable leadership through participation, engagement and good citizenship. SFCG’s overarching goal for its democracy and governance project is to: Strengthen democratic governance in the districts of Kono, Kailahun, and Koinadugu, and Tongo Fields in Sierra Leone, which supports Special Objective #2 (SO2) under USAID/Sierra Leone’s Transition Strategy Phase 2, (FY 2004-2006). SFCG’s program objective is to: Stimulate an active citizenry. This supports Intermediate Result (IR) 2.2: “Citizens, local government, and CSOs better informed on democratic governance” of SO2. -

BECE 2019 Schools 0Om Shared

SchNo SchName Sat S1 Ave Isc Grade S2 Ave LArts Grade S3 Ave Maths Grade S4 Ave SStds Grade Ave Agg Avg Ave Grade Pass_SS_Gen SS_Gen Pass Rate PROVIDENCE INTERNATIONAL 3598 SENIOR HIGH SCHOOL, FREETOWN 52 ISc 1.75 LArts 3.21 Maths 2.54 SStds 1.00 10.85 1.89 52 100.00% SOS HERMANN GMEINER 3685 INTERNATIONAL SCHOOL, MAKENI, 24 ISc 2.50 LArts 3.46 Maths 2.46 SStds 1.04 13.46 2.29 24 100.00% CLUNY FREE THE CHILDREN JSS., 3748 KOIDU 53 ISc 1.72 LArts 3.06 Maths 1.60 SStds 1.11 12.34 2.30 53 100.00% INTERNATIONAL ISLAMIC JNR. 3682 SECONDARY SCHOOL, CIRCULAR 21 ISc 2.14 LArts 3.38 Maths 2.76 SStds 1.19 13.24 2.42 21 100.00% LEBANESE SECONDARY SCHOOL, 3431 KENEMA 9 ISc 2.11 LArts 3.44 Maths 4.78 SStds 1.67 15.44 2.61 9 100.00% DELE PEDDLE INTERNATIONAL HIGH 3592 SCHOOL, ALLEN TOWN 38 ISc 2.68 LArts 3.24 Maths 2.29 SStds 1.29 13.95 2.63 38 100.00% HAMMOND INTERNATIONAL 3828 PREPARATORY SCHOOL AND 35 ISc 2.80 LArts 3.37 Maths 4.23 SStds 1.77 15.74 2.74 35 100.00% CHRISTIAN REFORMED CHURCH 3640 J.S.S., KABALA 26 ISc 3.35 LArts 3.69 Maths 3.12 SStds 1.69 15.50 2.81 26 100.00% MALAMAH COMPREHENSIVE 3841 ACADAMY,39A TARAWALLIE DRIVE, 62 ISc 1.48 LArts 5.15 Maths 3.13 SStds 1.87 15.68 2.82 62 100.00% UNIQUE INTERNATIONAL ACADEMY, 3753 KOIDU 69 ISc 2.61 LArts 5.30 Maths 4.52 SStds 3.16 18.29 2.84 69 100.00% LEONE INTERNATIONAL ACADEMY 3283 JR. -

Sierraleone Local Council Ward Boundary Delimitation Report

NATIONAL ELECTORAL COMMISSION Sierra Leone Local Council Ward Boundary Delimitation Report Volume Two Meets and Bounds April 2008 Table of Contents Preface ii A. Eastern region 1. Kailahun District Council 1 2. Kenema City Council 9 3. Kenema District Council 12 4. Koidu/New Sembehun City Council 22 5. Kono District Council 26 B. Northern Region 1. Makeni City Council 34 2. Bombali District Council 37 3. Kambia District Council 45 4. Koinadugu District Council 51 5. Port Loko District Council 57 6. Tonkolili District Council 66 C. Southern Region 1. Bo City Council 72 2. Bo District Council 75 3. Bonthe Municipal Council 80 4. Bonthe District Council 82 5. Moyamba District Council 86 6. Pujehun District Council 92 D. Western Region 1. Western Area Rural District Council 97 2. Freetown City Council 105 i Preface This part of the report on Electoral Ward Boundaries Delimitation process is a detailed description of each of the 394 Local Council Wards nationwide, comprising of Chiefdoms, Sections, Streets and other prominent features defining ward boundaries. It is the aspect that deals with the legal framework for the approved wards _____________________________ Dr. Christiana A. M Thorpe Chief Electoral Commissioner and Chair ii CONSTITUTIONAL INSTRUMENT No………………………..of 2008 Published: THE LOCAL GOVERNMENT ACT, 2004 (Act No. 1 of 2004) THE KAILAHUN DISTRICT COUNCIL (ESTABLISHMENT OF LOCALITY AND DELIMITATION OF WARDS) Order, 2008 Short title In exercise of the powers conferred upon him by subsection (2) of Section 2 of the Local Government Act, 2004, the President, acting on the recommendation of the Minister of Internal Affairs, Local Government and Rural Development, the Minister of Finance and Economic Development and the National Electoral Commission, hereby makes the following Order:‐ 1. -

2006 Report on Electoral Constituency

August 2006 Preface This part of the report on Electoral Constituency Boundaries Delimitation process is a detailed description of each approved constituency. It comprises the chiefdoms, streets and other prominent features defining constituency boundaries. It is the aspect that deals with the legal framework for the approved constituencies. Ms. Christiana A. M. Thorpe (Dr.) Chief Electoral Commissioner and Chairperson. I Table of Contents Page A. Eastern Region…………………..……………………1 1. Kailahun District ……………………………………1 2. Kenema District………………………..……………5 3. Kono District……………………….………………14 B. Northern Region………………………..……………19 1. Bombali District………………….………..………19 2. Kambia District………………………..…..………25 3. Koinadugu District………………………….……31 4. Port Loko District……………………….…………34 5. Tonkolili District……………………………………43 C. Southern District……………………………………47 1. Bo District…………………………..………………47 2. Bonthe District………………………………………54 3. Moyamba District……………….…………………56 4. Pujehun District……………………………………60 D. Western Region………………………….……………64 1. Western Rural …………………….…………….....64 2. Western Urban ………………………………………81 II EASTERN REGION KAILAHUN DISTRICT (01) DESCRIPTION OF CONSTITUENCIES Name & Code Description of Constituency Kailahun District This constituency comprises of part of Luawa chiefdom with the Constituency 1 following sections: Baoma, Gbela, Luawa Foguiya, ManoSewallu, Mofindo, and Upper Kpombali. (NEC Const. 001) The constituency boundary starts along the Guinea/Sierra Leone international boundary northeast where the chiefdom boundaries of Kissi Kama and Luawa meet. It follows the Kissi Kama Luawa chiefdom boundary north and generally southeast to the meeting point of Kissi Kama, Luawa and Kissi Tongi chiefdoms. It continues along the Luawa/Kissi Tongi boundary south, east then south to meet the Guinea boundary on the southeastern boundary of Upper Kpombali section in Luawa chiefdom. It continues west wards along the international boundary to the southern boundary of Upper Kpombali section. -

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees Policy Development and Evaluation Service (Pdes)

UNITED NATIONS HIGH COMMISSIONER FOR REFUGEES POLICY DEVELOPMENT AND EVALUATION SERVICE (PDES) A catalyst and a bridge An evaluation of UNHCR‟s community empowerment projects in Sierra Leone Claudena M. Skran PDES/2012/01 Independent consultant January 2012 Policy Development and Evaluation Service UNHCR‟s Policy Development and Evaluation Service (PDES) is committed to the systematic examination and assessment of UNHCR policies, programmes, projects and practices. PDES also promotes rigorous research on issues related to the work of UNHCR and encourages an active exchange of ideas and information between humanitarian practitioners, policymakers and the research community. All of these activities are undertaken with the purpose of strengthening UNHCR‟s operational effectiveness, thereby enhancing the organization‟s capacity to fulfil its mandate on behalf of refugees and other persons of concern to the Office. The work of the unit is guided by the principles of transparency, independence, consultation, relevance and integrity. Policy Development and Evaluation Service United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees Case Postale 2500 1211 Geneva 2 Switzerland Tel: (41 22) 739 8433 Fax: (41 22) 739 7344 e-mail: [email protected] internet: www.unhcr.org Printed by UNHCR All PDES evaluation reports are placed in the public domain. Electronic versions are posted on the UNHCR website and hard copies can be obtained by contacting PDES. They may be quoted, cited and copied, provided that the source is acknowledged. The views expressed in PDES publications are not necessarily those of UNHCR. The designations and maps used do not imply the expression of any opinion or recognition on the part of UNHCR concerning the legal status of a territory or of its authorities. -

The Role of Civil Society in Preventing and Curbing Corruption: Promoting Greater Transparency and Accountability

Aminata Kelly-Lamin, Regional Director, Network Movement for Justice and Development (NMJD), Sierra Leone Workshop 3.2 Anti-corruption practices in Non-Renewable Natural Resources for Sustainable Human Development, Thursday 16 Nov. 11:30-14:00 Topic: The Role of Civil Society in Preventing and Curbing Corruption: Promoting Greater Transparency and Accountability. Introduction I represent an organization that is working on mining, public accountability, policy advocacy, youth empowerment and human rights- that is the Network Movement for Justice and Development (NMJD). NMJD is a member of a coalition called the National Advocacy Coalition on Extractives which was born out of the desire to see the issues in the Non Renewable Natural Resource sector addressed. NMJD is also a member of the Civil Society Monitoring Group (CSMG). As a representative of that organization, I bring you all greetings in the struggle. Based on the vision of this noble organization, we believe that the utilization of natural resources in developing countries of the world today stand on the threshold of depletion and therefore requires rethinking of their exploitation as a means to economic development not as an end in itself. It is fast becoming clear that the promise that the Non Renewable Natural Resources held for Africa‘s economic growth over the decades has and is still being eroded by corrupt practices. Civil society as a term the world over has become an attractive notion to many groups, including politicians, scholars, advocacy and non-governmental organizations. This sector is viewed by these groups as a dynamic and innovative source for raising new concerns as well as articulating new directions. -

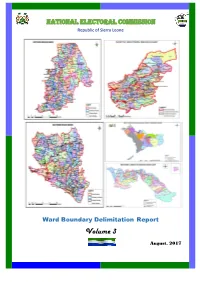

2017 Ward Description, Maps and Population

NATIONAL ELECTORAL COMMISSION Republic of Sierra Leone Ward Boundary Delimitation Report Volume 3 August, 2017 Foreword The National Electoral Commission (NEC) is submitting this report on the delimitation of constituency and ward boundaries in adherence to its constitutional mandate to delimit electoral constituency and ward boundaries, to be done “not less than five years and not more than seven years”; and complying with the timeline as stipulated in the NEC Electoral Calendar (2015-2019). The report is subject to Parliamentary approval, as enshrined in the 1991 Constitution of Sierra Leone (Act No 6 of 1991); which inter alia states delimitation of electoral boundaries to be done by NEC, while Section 38 (1) empowers the Commission to divide the country into constituencies for the purpose of electing Members of Parliament (MPs) using Single Member First- Past –the Post (FPTP) system. The Local Government Act of 2004, Part 1 –preliminary, assigns the task of drawing wards to NEC; while the Public Elections Act, 2012 (Section 14, sub-sections 1 &2) forms the legal basis for the allocation of council seats and delimitation of wards in Sierra Leone. The Commission appreciates the level of technical assistance, collaboration and cooperation it received from Statistics Sierra Leone (SSL), the Boundary Delimitation Technical Committee (BDTC), the Boundary Delimitation Monitoring Committee (BDMC), donor partners, line Ministries, Departments and Agencies and other key actors in the boundary delimitation exercise. The hiring of a Consultant, Dr Lisa Handley, an internationally renowned Boundary delimitation expert, added credence and credibility to the process as she provided professional advice which assisted in maintaining international standards and best practices. -

Report of the Second Annual General Meeting of the Peace Diamond Alliance Organized on 29-30 September 2004, Koidu Town, Sierra Leone

Report of the Second Annual General Meeting of the Peace Diamond Alliance 29-30 September 2004, Koidu Town, Sierra Leone September 2004 Prepared by Management Systems International Under USAID Cooperative Agreement No. 636-A-00-03-00038-00 Sierra Leone U.S.A. 47 Wellington Street 600 Water St., SW Freetown - Sierra Leone Washington, D.C. Tel: (232) 22-227-7241 Cell: (232) 76-601-491 (202) 484-7170 e-mail: [email protected] e-mail: [email protected] www.peacediamonds.org www.msiworldwide.com ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Members of the Peace Diamond Alliance wish to thank the people of Koidu and members of the local district and town councils for hosting the Second Annual General Meeting. The Alliance extends its sympathy to the family of the late Paramount Chief F J M Saquee 1V of Tankoro Chiefdom, who’s guiding light in the creation of the Alliance, still shines. The venue for this meeting was the brainchild of Ms. Satta Kumba Tondoneh who was cruelly taken from the people of Koidu in a tragic helicopter crash in June 2004. The Kaamayamusu Resource Centre stands as a constant reminder of her efforts. The Peace Diamond Alliance appreciates the continued support of USAID and DfID, and the efforts of the EU, the UN and in particular UNAMSIL within the Diamond Sector. To Hon. Theresa J. Koroma, Deputy Minister of Trade and Industry, whose continued support to cooperatives has been an inspiration, a special thanks for her enormous contribution. Appreciation is also extended to all other members of the Government of Sierra Leone whose presence and endorsements have served to underscore the importance of this venture and to give members increased strength as they strive to ensure that a transparent Diamond industry in Sierra Leone becomes the backbone of the nation’s reconstruction. -

The Alluvial Diamond Mining Ordinance, 1956

Alluvial Diamond Mining [Cap. 198 1753 CHAPTER 198. ALLUVIAL DIAMOND MINING. P.N. LICENSED DIAMOND MINING AREAS 34 of 1957. declared by the Minister to be such, under sub-section 3 ( 1). 50 of 1957. 81 of 1957. 116 of 1958. 59 of 1959. 138 of 1959. 152 of 1959. 154 of 1959. 1. This Declaration may be cited as the Alluvial Diamond Citation. Mining (Licensed Diamond Mining Areas) Declaration. 2. The chiefdoms or parts of chiefdoms listed in the Schedule Declaration. are hereby declared to be licensed alluvial diamond mining areas with effect from the dates stated in the said schedule. SCHEDULE. 1. The following chiefdoms of the Bo District, with effect from the 6th day of February, 1956- BAOMA, BuMPE, JAIAMA-BoNGo, LuBu, TrKONKO. 2. The following chiefdoms of the Kenema District, with effect from the 6th day of February, 1956- KANDU-LEPPIAMA, SIMBARU, WANDO. 3. The following chiefdoms of the Bo District, with effect from the 1st day of March, 1956- BADJA, KAKUA, KoMBOYA. 4. The following chiefdoms of the Kenema District, with effect from the 1st day of March, 1956- GoRAMA MENDE, NoNGOWA, SMALL Bo. 5. The DAMA Chiefdom of the Kenema District, with effect from the 11th day of June, 1956. 6. The following part of the LowER BAMBARA Chiefdom in the Kenema District, with effect from the 28th day of March, 1957- ALL THA'rPARCEL OF LAND of the LowER BAMBARA Chiefdom in the Kenema District of the South-eastern Province of the Protectorate of Sierra Leone the boundary whereof commencing at a point which is on a true bearing of 119° 30' and a distance of 10,000 feet approximately from Panguma Town and which is the centre of the Panguma-Kenema Motor Road bridge over the River Tongo and which is also Point Number 3 of Mining Lease 2001 and thence in a southerly direction following the East gutter of the Panguma-Kenema road for a distance of apProximately 3·7 miles to Point Number 4 of Mining Lease 2001 and 1754 Cap. -

African Studhe

•MSTITUTE AFRICANOFSTUDHE FOURAH BAY COLLEGE _ UNIVERSITY OF SIERRA LEONE 23 JUW «75 TRICANA JLLETIN FORMER FOURAH BAY COLLEGE CLINETOWN, FREETOWN. Vol. Ill No. 2 Session 1972-73 JANUARY 1973 Sditor: J. G. EDOWU HYDE Asst. Editor: J. A. :>. BL/.1R AFRICAI'!A RESEARCH BULLETIN CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION J. G." Edowu Hyde 1 1. ARTICLES Migration into a Small Temne Town in Central Sierra Leone ...a.oo.o.o... o.o....0.0. L. Ro MlllS 3 A Brief History of Nimikoro Chiefdom, Kono District • Sahr Matturi 28 2. RESEARCH NOTE Mende Influence on Kono ...................... Arthur Abraham 44 3. NEWS ITEMS Research Report on Customary Family Law Project ............. Barbara E. Harrell-Bond 47 Notes for the Guidance of Visiting Research Scholars 53 Current Research at Fourah Bay College 58 INTRODUCTION The Bulletin opens with an article "by Dr» L. R. Mills on migration into a small town in Bierra Leone it is the result of his association with an inter¬ disciplinary research team, the Kono Road Project, Institute of African Studies, studying the effects of a new major road. In a detailed study of immi¬ grants Dr. Mills has determined' their character¬ istics as well as the reasons for migration into the town, Matotoka. The origins of the migrants have been furnished both by a map and a table. Above all, he has used the study to test hypotheses developed by Ravenstein in the late nineteenth century and based largely on research in Europe and North America. Dr. Mills, who is a member of the United Nations Demographic Unit, Fourah Bay College is on secondment from the University of Durham. -

Sierra Leone 2004

Diamond Industry sierra Annual Review leone2004 Smoke and Mirrors: An Environmentalist’s Development Diamonds? The “1414” Stone .............2 Nightmare........................7 Editorial Comment Diamonds: The Political Governance: and Historical Context....2 An Uphill Struggle...........8 It is now two years since Sierra Leone’s war formally ended. Fuelled largely by diamonds and History and Size of Kimberley Process corruption – the two were very closely linked – the decade-long conflict drew much-needed The Diamond Industry ....2 Compliance......................9 international attention to the processes of diamond mining and trading. Since their commercial The Miners .......................3 Beneficiation .................10 exploitation began in the 1930s, diamonds have influenced Sierra Leone’s fortunes in ways that DiamondWorks: Peace Diamond Alliance no other economic activity has. Accounting for more than two-thirds of the nation’s export earnings A New Face ......................4 Enters Second Year.......11 and a quarter of GDP for the early years of the post-colonial period, diamonds have been profoundly influential in shaping Sierra Leone’s history and its social and political life, for good and ill. The Dealers......................5 Campaign for Just Mining.....................11 During the 1990s, the trajectory of the diamond industry in Sierra Leone was wholly negative: Two Dealers .....................5 A Rights-Based diamonds were implicated in the decade-long conflict which almost completely destroyed the The Exporters ..................6 Approach to Mining ......12 country and led to the deaths of upwards of 75,000 of its citizens. Hisham Mackie: Endnotes and International attention, as a result, has until recently focused on how the gems are traded – Sierra Leone’s Biggest Acknowledgements ......12 their movement to the international market. -

Reclaiming the Land After Mining

Reclaiming the Land After Mining Improving Environmental Management and Mitigating Land-Use Conflicts in Alluvial Diamond Fields in Sierra Leone Foundation For Environmental Security & Sustainability July 2007 The Foundation for Environmental Security and Sustainability (FESS) works to improve environmental security around the world, focusing in particular on the fragile relationship between populations and the environment in developing countries where many people are directly dependent on natural resources for their livelihoods. FESS works with government officials, researchers, civil society organizations, and the private sector to increase awareness of how the mismanagement and abuse of natural resources can lead to social, economic, and political instabilities that can contribute to social tension and even violent conflict. To address environmental risks to stability, FESS conducts research and implements community-driven projects that promote sustainable management of natural resources and the environment. This report was made possible through a grant from the Environment Program of the Tiffany & Co. Foundation and core funding from the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID). The contents are the responsibility of the Foundation for Environmental Security and Sustainability and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Tiffany & Co. Foundation, USAID, or the United States Government. For more information, please contact FESS at [email protected]. Acknowledgement FESS would like to thank the staff at USAID/EGAT/ESP in Washington, D.C. as well as the USAID Mission in Freetown and the IDMP offices in Koidu and Tongo Fields for their encouragement and support. Map 1: Sierra Leone, West Africa Map 2: Kono and Kenema Districts, Sierra Leone Executive Summary Improving Environmental Management and Mitigating Land-Use Conflicts in Alluvial Diamond Fields in Sierra Leone The Foundation for Environmental Security and Sustainability (FESS) designed and implemented the project with the support of a grant from the Tiffany & Co.