2016/2017 Needs Assessment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New South Wales Class 1 Load Carrying Vehicle Operator’S Guide

New South Wales Class 1 Load Carrying Vehicle Operator’s Guide Important: This Operator’s Guide is for three Notices separated by Part A, Part B and Part C. Please read sections carefully as separate conditions may apply. For enquiries about roads and restrictions listed in this document please contact Transport for NSW Road Access unit: [email protected] 27 October 2020 New South Wales Class 1 Load Carrying Vehicle Operator’s Guide Contents Purpose ................................................................................................................................................................... 4 Definitions ............................................................................................................................................................... 4 NSW Travel Zones .................................................................................................................................................... 5 Part A – NSW Class 1 Load Carrying Vehicles Notice ................................................................................................ 9 About the Notice ..................................................................................................................................................... 9 1: Travel Conditions ................................................................................................................................................. 9 1.1 Pilot and Escort Requirements .......................................................................................................................... -

The Benefits of Long-Term Pavement Performance (LTPP) Research to Funders

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com ScienceDirect Transportation Research Procedia 14 ( 2016 ) 2477 – 2486 6th Transport Research Arena April 18-21, 2016 The benefits of Long-Term Pavement Performance (LTPP) research to funders Tim Martin a,*, Lith Choummanivong a aARRB Group Ltd, 500 Burwood Highway, Vermont South, Victora, 3133, Australia Abstract Long-term pavement performance (LTPP) monitoring has been conducted in Australia for over 20 years. This research was funded by Austroads (representing federal, state and territory road agencies, local government and the New Zealand road agency) to promote improved practice and capability for the road agencies. The LTPP monitoring program measured performance by rutting, roughness, cracking and deflection. Initially the program involved a range of designated flexible pavement sites under varying conditions of environment and traffic. Many of these LTPP sites were included in the Strategic Highway Research Program (SHRP) of the United States (US). All sites were monitored in accordance with the SHRP protocols. Later long-term pavement performance maintenance (LTPPM) sites were included in the program to: (i) assess the impact of surface maintenance treatments on changes to pavement conditions (works effects, WE); and, (ii) assess the impact of maintenance on road deterioration (RD). A range of RD and WE models were developed using the LTPP/LTPPM observational data in combination with experimental data collected from Australia's Accelerated Loading Facility (ALF) that separately investigated the impact on RD of increased axle load and various typical surface maintenance treatments. The RD models cover the deterministic prediction of functional surface distress (rutting, roughness and cracking) and the loss of traffic load capacity (strength). -

Intersection Improvements on Great Western Highway at Pitt Street and Marsden Street, Parramatta Roads and Maritime Services | May 2019

Intersection improvements on Great Western Highway at Pitt Street and Marsden Street, Parramatta Roads and Maritime Services | May 2019 The NSW Government is funding this work as part Community benefits of its $30 million Parramatta Congestion Improvement Program. • Improving access to and from the Parramatta CBD. Roads and Maritime Services is improving the • Addressing increased traffic on the intersections of Pitt Street and Marsden Street along the Great Western Highway, Parramatta. surrounding road network. • Increasing safety for all road users We need to close two sections of Marsden Street, • Reducing queue lengths and increase either side of the Great Western Highway, for two through traffic night shifts from Sunday 2 June. • Facilitating growth and development in More information about the two closures is on the Parramatta and surrounding areas. next page and detour maps are available on the project website. 1 For the latest traffic updates, you can call Our work schedule 132 701, visit livetraffic.com or download the Between May and June we will be working up Live Traffic NSW App. to and six days five nights a week. Our night work hours will be between 8pm and 5am from Sunday to Friday. Contact If you have any questions, please contact our Our day work hours will be between 7am and 6pm from Monday to Friday and between 8am delivery partner, DM Roads, and 1pm on Saturdays. on 1800 332 660 or [email protected]. We will not be working public holidays. For more information on this project, visit rms.work/pcip. Work to date Thank you for patience during this important Since our last project update we have completed: work. -

The Vegetation of the Western Blue Mountains Including the Capertee, Coxs, Jenolan & Gurnang Areas

Department of Environment and Conservation (NSW) The Vegetation of the Western Blue Mountains including the Capertee, Coxs, Jenolan & Gurnang Areas Volume 1: Technical Report Hawkesbury-Nepean CMA CATCHMENT MANAGEMENT AUTHORITY The Vegetation of the Western Blue Mountains (including the Capertee, Cox’s, Jenolan and Gurnang Areas) Volume 1: Technical Report (Final V1.1) Project funded by the Hawkesbury – Nepean Catchment Management Authority Information and Assessment Section Metropolitan Branch Environmental Protection and Regulation Division Department of Environment and Conservation July 2006 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This project has been completed by the Special thanks to: Information and Assessment Section, Metropolitan Branch. The numerous land owners including State Forests of NSW who allowed access to their Section Head, Information and Assessment properties. Julie Ravallion The Department of Natural Resources, Forests NSW and Hawkesbury – Nepean CMA for Coordinator, Bioregional Data Group comments on early drafts. Daniel Connolly This report should be referenced as follows: Vegetation Project Officer DEC (2006) The Vegetation of the Western Blue Mountains. Unpublished report funded by Greg Steenbeeke the Hawkesbury – Nepean Catchment Management Authority. Department of GIS, Data Management and Database Environment and Conservation, Hurstville. Coordination Peter Ewin Photos Kylie Madden Vegetation community profile photographs by Greg Steenbeeke Greg Steenbeeke unless otherwise noted. Feature cover photo by Greg Steenbeeke. All Logistics -

Great Western Highway Upgrade Program Project Benefits Fact Sheet October 2020

Transport for NSW Great Western Highway Upgrade Program Project benefits fact sheet October 2020 The upgrade program will reduce congestion and improve safety on the highway The NSW Government is investing $2.5 billion towards upgrading the Great Western Highway between Katoomba and Lithgow to a four lane carriageway. Once completed, the upgrade will reduce congestion and deliver safer, more efficient and reliable journeys for those travelling in, around and through the Blue Mountains, while also better connecting communities in the Central West. The Great Western Highway Upgrade Program • Enhance liveability and amenity: aims to: maintain and improve local amenity and • Improve safety: reducing safety risks along character, and protect environmental the corridor for all road users and cultural assets • Improve network performance: improve • Improve resilience and future proof: provide congestion and travel time reliability a dependable and adaptable transport network that enables continuity of transport • Improve and drive regional economic and essential services. development and productivity nswroads.work/greatwesternhighway Page 1 of 4 Improve safety Improve network performance The upgrade program aims to reduce crash The Great Western Highway is a key corridor rates between Katoomba and Lithgow, which of national significance and has rising traffic are currently higher than the NSW average for volumes. The daily average traffic volume similar roads. entering/exiting Blackheath is more than Transport for NSW has recorded a 77% 16,000 vehicles. reduction in fatal crashes and a 28% This volume is greater than the daily volumes reduction in casualties between Leura and on already duplicated highways such as the Warrimoo since the highway was duplicated Hume Highway at Goulburn, the Princes and upgraded. -

Regional and Interstate Transport Summary 10.1 Snapshot • Regional and Interstate Transport Infrastructure • a Number of Major Road Programs Are Underway

10.0 Regional and interstate transport Summary 10.1 Snapshot • Regional and interstate transport infrastructure • A number of major road programs are underway. • Long distances, low population densities and the supports the economy and quality of life of These include upgrades to the Pacific Highway nature of regional employment means the demands NSW by allowing people to access employment and Princes Highway. Getting the best value for placed by passengers on the transport networks opportunities, connecting regional communities these major investments is essential. Infrastructure of Regional NSW are very different to those of and supporting freight movements. NSW is concerned that cost estimates for these metropolitan NSW. programs appear very high. • Regional NSW has extensive and well–developed • The road network is the dominant mode for regional regional road and rail networks connecting • Unlocking the key constraints along the road and passenger travel. Over 90 percent of the 7.5 million population and employment centres across rail networks that limit freight movements are likely journeys made each day are by car1. the state. In recent years, the NSW State and to have some of the highest economic benefits in Commonwealth Governments have undertaken the regions. This includes upgrading understrength • There is limited usage of regional and interstate public major investment to improve the quality and road bridges, providing rail passing loops and transport. Regional train services carry less than capacity of these networks. ensuring roads and rail lines are well-maintained 6,000 passengers a day. Regional bus and coach and effectively managed. services transport around almost three times as • The road network is the backbone of regional many, approximately 15,000 passengers a day2. -

Suggested-Itineries.Pdf

This Group Planner is a resource for creating dynamic, diverse and experiential itineraries for your clients. It is a practical guide that will assist you in organising your group visit to the region. Providing truly authentic experiences, dramatic perspectives, dreamtime moments and sharing the beauty and uniqueness of our World Heritage listed surrounds is a priority and a privilege for our operators. The Blue Mountains Lithgow and A PLACE Oberon Region offers a world class SPECIAL array of nature, cultural, historical, lifestyle and adventure activities and experiences. We look forward to welcoming your group to our region. The Greater Blue Mountains World Heritage Area is Australia’s most accessible wilderness. Stretching over one million hectares, the region is an inspiring and diverse mix of rainforest, blue-hazed valleys, golden stone escarpments, canyons, tall forests and windswept heathlands. It is one of Australia’s iconic landscapes and has received National Landscape status in The Greater Blue Mountains received World recognition of its world class Heritage Listing in 2000 in recognition of experiences of environmental and its outstanding universal natural value and cultural significance. conservation of biological diversity. Despite the descriptor, the Blue Mountains Six Aboriginal language groups treasure The region is Australia’s ‘cradle of are not, as the name suggests, mountains, their connections with the land — the conservation’ renowned for its bushwalking but in fact are dissected sandstone plateaux Darug, Gundungurra, Dharawal, Darkinjung, and inspiring scenery. This wonderful which shelter a rich diversity of plant and Wanaruah and Wiradjuri people. These wilderness is on Sydney’s doorstep but it animal life. -

Great Western Highway Upgrade Program Overview and Strategic Corridor

FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS NOVEMBER 2019 Great Western Highway Upgrade Program Overview and strategic corridor Great Western Highway from Mount Boyce looking north What is the Great Western Highway What has happened to date? Upgrade Program? By 2015, the Great Western Highway had been The Great Western Highway Upgrade Program will upgraded to two lanes in each direction between Emu deliver around 34 kilometres of four lane divided Plains and Katoomba. A proposed corridor for upgrade highway between Katoomba and Lithgow. between Mount Victoria and Lithgow was reserved in 2013 and appears in the Blue Mountains City Council’s The program is currently in the early stages of planning; and Lithgow City Council’s Local Environmental Plans. we are presenting a strategic corridor between Katoomba and Mount Victoria for public consultation Since then, the NSW Government has progressively and the corridor reserved in 2013 between Mount upgraded further sections of the highway, with the most Victoria to Lithgow (South Bowenfels). recent project at Kelso opened to traffic in March 2017. In 2018, the NSW Government announced $30 million The NSW Government has committed $2.5 billion to upgrade Kelso to Raglan. The Australian and NSW in funding towards the planning and delivery of Governments have spent $250 million to prioritise safety the duplication. improvements along the Great Western Highway at Blackheath, Mount Victoria, and Forty Bends. Once the highway has been upgraded between Katoomba and Lithgow, road users will save at least 10 minutes in travel time and over 95km would be two lanes each way between Emu Plains and Wallerawang. -

Sydney Map 150-32

Wingen Rookhurst 34 A B 34 CDMoonan Flat Upper Bowman JOINS JOINS MAP 150-32 JOINS 150-29 39 Barrington Tops 45 10 Barrington 148 -29 Parkville 31 National Park Rawdon Vale 152-29 150º 151º Woolooma Copeland 9 152º 41 Cassilis 18 Belltrees 32º Gundy Mt Barrington V Maudeville Gloucester 32º 9 Borambil 34 Owens Scone Bunnan Gap Forbesdale GOLDEN ENGLAND Terragong Lake Faulkland 13 Glenbawn V 33 30 20 Gloucester Stratford Tur ill 9 41 Bow Davis Tops Merriwa Aberdeen Barrington Tops Wappinguy 25 Dangarfield Creek National Park Craven Manobalai Chichester Bucketts 34 HWY Kayuga Salisbury Wards River 114 Castle Rock 12 Underbank 1 Bandon Grove 1 Goulburn River Gungal 24 Muswellbrook Bowmans Creek Halton Main Creek National Park 27 Sandy Hollow Munni Markwell 15 26 Bendolba Fosterton Stroud Road 13 NEW 29 Hume Lake Allynbrook Wollar 16 Liddell Greeland St Clair 26 13 28 Denman 28 Stroud Baerami Gresford Dungog GOLDEN 47 Bylong Kerrabee 25 Ravensworth Tyraman 29 Jerrys 16 Booral Plains Camberwell Glendon Wallarobba V Tal Tal Mountain Brook Girvan Maison 19 Brookfield Glen Dieu Allworth Widden Redbournberry Vacy Martins Baerami Gallic Doyles 30 Clarence Creek Creek 52 Creek 10 Singleton Town Limeburners HW River Creek Y Paterson HWY Holbrook Mt Wambo V 21 22 21 Lue 11 Branxton Seaham Wollemi National Park Bulga Belford 15 Woodville Karuah 23 22 Wallalong 1 Swan 15 Greta FIC Bay Soldiers Breakfast Creek 69 17 Point V Rothbury Rutherford Maitland Nelson Bay 2 Mt Coriaday 37 Broke PACI Medowie 51 Metford 2 Rylstone Kurri 18 Raymond Terrace Anna -

The Great North Road

THE GREAT NORTH ROAD NSW NOMINATION FOR NATIONAL ENGINEERING LANDMARK Engineering Heritage Committee Newcastle Division Institution of Engineers, Australia May 2001 Introduction The Newcastle Division's Engineering Heritage Committee has prepared this National Engineering Landmark plaque nomination submission for the total length of the Great North Road from Sydney to the Hunter Valley, NSW. The Great North Road was constructed between 1826 and 1836 to connect Sydney to the rapidly developing Hunter Valley area. It was constructed using convict labour, the majority in chain gangs, under the supervision of colonial engineers, including Lieutenant Percy Simpson. Arrangements have been made to hold the plaquing ceremony on the 13 October 2001 to coincide with the National Engineering Heritage Conference in Canberra the previous week. Her Excellency Professor Marie Bashir AC, Governor of New South Wales, has accepted our invitation to attend the plaquing ceremony as our principal guest. A copy of the Governor's letter of acceptance is attached. Clockwise from top left: general view downhill before pavement resurfacing; culvert outlet in buttress; buttressed retaining wall; new entrance gates, and possible plaque position, at bottom of Devines Hill; typical culvert outlet in retaining wall. Commemorative Plaque Nomination Form To: Commemorative Plaque Sub-Committee Date: 22 May 2001 The Institution of Engineers, Australia From: Newcastle Division Engineering House Engineering Heritage Committee 11 National Circuit (Nominating Body) BARTON ACT 2600 The following work is nominated for a National Engineering Landmark Name of work: Great North Road, NSW Location: From Sydney to the Hunter Valley via Wisemans Ferry and Wollombi (over 240 km in length) Owner: Numerous bodies including NSW Roads & Traffic Authority, NSW National Parks & Wildlife Service (NPWS), local councils and private landowners (proposed plaque site located on NPWS land). -

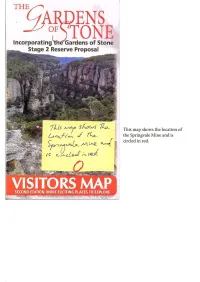

__ . ENS TONE Incorporating( the Gardens of Stone Stage 2 Reserve Proposal

__ _. ENS TONE Incorporating (the Gardens of Stone Stage 2 Reserve Proposal This map shows the location of the Springvale Mine and is circled in red. to Rylstone +Tayan Peak I I 25km \ ) WOLLEMI NATIONAL 1154m I \ BOGEE N:----!.: ( ,,1. t ( \ ) \ u~ ' \ r \ ( \ ,I ,» PARK J (] ENS ) I ( \ \ OF J {\l I I I t, -to TONE - ~O' Incorporating (th·e Garde~s of Stone WOLLEMI ' \ I CAPERTEE \ --, Stage 2 Reserve Pr,posal \ SECOND EDITION. MORE EXCITING PLAC:ES TO EXPLORE Ck / r ) NATIONAL I GARDENS OF STONE PROPOSAL DIVISION AREAS I Listed from north to sout h I NATIONAL( I Note: For detailed descriptions of Proposal areas see t e other side of the map, ) I , ..... ';' I I 111 1 // I PARK Mugii Murum-ban State Conservation Area, reserved arch 2011 _..'\.Private - - 1 I (a future extension to Gardens of Stone Natfonal / - - -..-., (jI _,,./ I I I Pik) I PARK I .......-. / - ( l) ('/~ ;j. ~ _ ......... ..... l I Other land _.,..,,. (\'3 \ ro.id.,,.,,. I ~o ....__,,,.- I (for protection as extensions to Wollemi and Garde s of Stone National Parks) Creek I CJ Propo1ed I /0° Capertee Natiooa l Pork I Genowlan I I 1 Ben Bullen State Forest and Wolgan State Forest, on t~e Great Dividing Range 1 ', \,t ,,- I 6t,mioo ; oint (for protection as Gardens of Stone State Conservation Area) A/J I CJ ' I \ o \ -o Saddle ' I I ' \ \ / ::1. ~ Lookout 1"1025 ' Newnes Plateau (for protection as Gardens of Stone State Conservation Area) I! Point :_ ' \ ··,, -~-------, , 1 ~ Hatteras CJ ,.(]. J • / ) ,.\a. •_/H~r7f~ II j j i 'Vf r Wollangambe Wilderness and other Identified Wil dern l s, NPWS 1997 \ or{ 1hc.lle ; ( ) / I (for protection as Gardens of Stone State Conservation Area) !!:1111.\" • i ' ,-, , CJ Mount; , •• --'·-,I Mugii 11111 '--,, I CAPERr1:1:~~;;,_ ,, , A1rly ·"'.::-/ ': , f 1034 J! ;.·-· ,,.-.,, -- ' / ,•The Western Escarpment (for protection as extensions Blue Mountains National Park) ~ s / " 1, l l <J ( Airly~:,: / Grotto Murum-ban CJ r,.11\'I ..,-- Turret \,{f' Genowlan 0/<<;;_-----<--p-,.,..-~ ~ =-,,,,~ / .,,. -

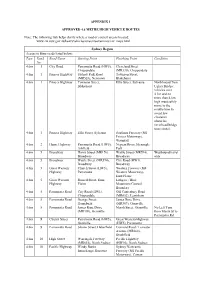

APPENDIX 1 APPROVED 4.6 METRE HIGH VEHICLE ROUTES Note: The

APPENDIX 1 APPROVED 4.6 METRE HIGH VEHICLE ROUTES Note: The following link helps clarify where a road or council area is located: www.rta.nsw.gov.au/heavyvehicles/oversizeovermass/rav_maps.html Sydney Region Access to State roads listed below: Type Road Road Name Starting Point Finishing Point Condition No 4.6m 1 City Road Parramatta Road (HW5), Cleveland Street Chippendale (MR330), Chippendale 4.6m 1 Princes Highway Sydney Park Road Townson Street, (MR528), Newtown Blakehurst 4.6m 1 Princes Highway Townson Street, Ellis Street, Sylvania Northbound Tom Blakehurst Ugly's Bridge: vehicles over 4.3m and no more than 4.6m high must safely move to the middle lane to avoid low clearance obstacles (overhead bridge truss struts). 4.6m 1 Princes Highway Ellis Street, Sylvania Southern Freeway (M1 Princes Motorway), Waterfall 4.6m 2 Hume Highway Parramatta Road (HW5), Nepean River, Menangle Ashfield Park 4.6m 5 Broadway Harris Street (MR170), Wattle Street (MR594), Westbound travel Broadway Broadway only 4.6m 5 Broadway Wattle Street (MR594), City Road (HW1), Broadway Broadway 4.6m 5 Great Western Church Street (HW5), Western Freeway (M4 Highway Parramatta Western Motorway), Emu Plains 4.6m 5 Great Western Russell Street, Emu Lithgow / Blue Highway Plains Mountains Council Boundary 4.6m 5 Parramatta Road City Road (HW1), Old Canterbury Road Chippendale (MR652), Lewisham 4.6m 5 Parramatta Road George Street, James Ruse Drive Homebush (MR309), Granville 4.6m 5 Parramatta Road James Ruse Drive Marsh Street, Granville No Left Turn (MR309), Granville