Interview with Mike Churchill

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Old Vic Season 4: Part 2

PRESS RELEASE FRIDAY 14 SEPTEMBER THE OLD VIC SEASON 4: PART 2 Matthew Warchus’ fourth season as Artistic Director of The Old Vic completes with an Arthur Miller double-bill, a World Premiere by Lucy Prebble and a special One Voice performance. These productions form Part 2 of the season, and follow the previously announced Part 1 consisting of ZooNation: The Kate Prince Company’s production of SYLVIA; Annie-B Parson’s 17c; Emma Rice’s Wise Children; and A Christmas Carol – for which today we also announce further casting. • Visionary director Rachel Chavkin makes her Old Vic debut directing Arthur Miller’s The American Clock from 4 February • Jeremy Herrin directs Sally Field, Bill Pullman, Jenna Coleman and Colin Morgan in Arthur Miller’s American classic All My Sons in a co-production with Headlong from 15 April • Closing the season is A Very Expensive Poison – a new play by Lucy Prebble based on the book by Luke Harding • A special One Voice performance to mark 100 years since the Armistice, Remembrance curated by Arinzé Kene and directed by Annabel Bolton • Further casting is announced for Jack Thorne’s version of A Christmas Carol directed by Matthew Warchus and starring Stephen Tompkinson as Ebenezer Scrooge. Coming soon: • A musical adaptation of the hit 1983 film, Local Hero, adapted by David Greig and Bill Forsyth, directed by John Crowley and with music and lyrics by Mark Knopfler, will come to The Old Vic in June 2020 following its world premiere at the Royal Lyceum Theatre Edinburgh in 2019. From The Old Vic: • Girl from the North Country opens on 1 October at the Public Theater, New York, and performances have been extended until 9 December. -

![Theater Souvenir Programs Guide [1881-1979]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6681/theater-souvenir-programs-guide-1881-1979-256681.webp)

Theater Souvenir Programs Guide [1881-1979]

Theater Souvenir Programs Guide [1881-1979] RBC PN2037 .T54 1881 Choose which boxes you want to see, go to SearchWorks record, and page boxes electronically. BOX 1 1: An Illustrated Record by "The Sphere" of the Gilbert & Sullivan Operas 1939 (1939). Note: Operas: The Mikado; The Goldoliers; Iolanthe; Trial by Jury; The Pirates of Penzance; The Yeomen of the Guard; Patience; Princess Ida; Ruddigore; H.M.S. Pinafore; The Grand Duke; Utopia, Limited; The Sorcerer. 2: Glyndebourne Festival Opera (1960). Note: 26th Anniversary of the Glyndebourne Festival, operas: I Puritani; Falstaff; Der Rosenkavalier; Don Giovanni; La Cenerentola; Die Zauberflöte. 3: Parts I Have Played: Mr. Martin Harvey (1881-1909). Note: 30 Photographs and A Biographical Sketch. 4: Souvenir of The Christian King (Or Alfred of "Engle-Land"), by Wilson Barrett. Note: Photographs by W. & D. Downey. 5: Adelphi Theatre : Adelphi Theatre Souvenir of the 200th Performance of "Tina" (1916). 6: Comedy Theatre : Souvenir of "Sunday" (1904), by Thomas Raceward. 7: Daly's Theatre : The Lady of the Rose: Souvenir of Anniversary Perforamnce Feb. 21, 1923 (1923), by Frederick Lonsdale. Note: Musical theater. 8: Drury Lane Theatre : The Pageant of Drury Lane Theatre (1918), by Louis N. Parker. Note: In celebration of the 21 years of management by Arthur Collins. 9: Duke of York's Theatre : Souvenir of the 200th Performance of "The Admirable Crichton" (1902), by J.M. Barrie. Note: Oil paintings by Chas. A. Buchel, produced under the management of Charles Frohman. 10: Gaiety Theatre : The Orchid (1904), by James T. Tanner. Note: Managing Director, Mr. George Edwardes, musical comedy. -

Hw Biography 2021

HUGH WOOLDRIDGE Director and Lighting Designer; Visiting Professor Hugh Wooldridge has produced, directed and devised theatre and television productions all over the world. He has taught and given master-classes in the UK, Europe, the US, South Africa and Australia. He trained at the London Academy of Music and Dramatic Art (LAMDA) and made his West End debut as an actor in The Dame of Sark with Dame Celia Johnson. Subsequently he performed with the London Festival Ballet / English National Ballet in the world premiere production of Romeo and Juliet choreographed by Rudolph Nureyev. At the age of 22, he directed The World of Giselle for Dame Ninette de Valois and the Royal Ballet. Since this time, he has designed lighting for new choreography with dance companies around the world including The Royal Ballet, Dance Theatre London, Rambert Dance Company, the National Youth Ballet and the English National Ballet Company. He directed the world premieres of the Graham Collier / Malcolm Lowry Jazz Suite Under A Volcano and The Undisput’d Monarch of the English Stage with Gary Bond portraying David Garrick; the Charles Strouse opera, Nightingale with Sarah Brightman at the Buxton Opera Festival; Francis Wyndham’s Abel and Cain (Haymarket, Leicester) with Peter Eyre and Sean Baker. He directed and lit the original award-winning Jeeves Takes Charge at the Lyric Hammersmith; the first productions of the Andrew Lloyd Webber and T. S. Eliot Cats (Sydmonton Festival), and the Andrew Lloyd Webber / Don Black song-cycle Tell Me 0n a Sunday with Marti Webb at the Royalty (now Peacock) Theatre; also Lloyd Webber’s Variations at the Royal Festival Hall (later combined together to become Song and Dance) and Liz Robertson’s one-woman show Just Liz compiled by Alan Jay Lerner at the Duke of York’s Theatre, London. -

Charlie Stemp and Danielle Hope to Play the Prince and Snow White in S N O W W H I T E at T H E L O N D O N P a L L a D I U M

CHARLIE STEMP AND DANIELLE HOPE TO PLAY THE PRINCE AND SNOW WHITE IN S N O W W H I T E AT T H E L O N D O N P A L L A D I U M Qdos Entertainment today (12 October 2018) announced that Charlie Stemp will return to the London Palladium to play The Prince in this year’s Pantomime, Snow White at the London Palladium along with Danielle Hope who will play the title role of Snow White. They join the previously announced Dawn French as The Wicked Queen, Julian Clary as The Man in The Mirror, Paul Zerdin as Muddles, Nigel Havers as The Understudy, Gary Wilmot as Mrs Crumble with Vincent and Flavia as The King and The Queen for this strictly limited 5 week run. They are joined by Josh Bennett, Simeon Dyer, Craig Garner, Ben Goffe, Jamie John, Blake Lisle and Andrew Martin as The Magnificent Seven and ensemble members Faye Best, Myles Brown, Darragh Cowley, Ivan De Freitas, Scott English, Liz Ewing, Ross Finnie, Diana Girbau, Matt Holland, Abigayle Honeywill, Stevie Hutchinson, Jemima Loddy, Megan Louch, Mollie McGugan, James Paterson, Leanne Pinder, Oliver Roll, Jordan Rose, Aaron J Smith, Lucie-Mae Sumner, Carrie Sutton, Grant Thresh and Charlotte Wilmot along with The Palladium Pantoloons. Performances of Snow White at the London Palladium begin on Saturday 8 December 2018 with Gala Night on 12 December with the run concluding on Sunday 13 January 2019. Produced by the Olivier Award-winning team behind last year’s Dick Whittington, Snow White at the London Palladium will again be directed by Michael Harrison, with choreography by Karen Bruce, scenery designed by Ian Westbrook, costumes designed by Hugh Durrant, speciality costumes designed by Mike Coltman, visual special effects by The Twins FX, lighting by Ben Cracknell, sound design by Gareth Owen, video and projection design by Duncan McLean, and original music by Gary Hind. -

Women in Theatre 2006 Survey

WOMEN IN THEATRE 2006 SURVEY Sphinx Theatre Company 2006 copyright. No part of this survey may be reproduced without permission WOMEN IN THEATRE 2006 SURVEY Sphinx Theatre Company copyright 2006. No part of this survey may be reproduced without permission The comparative employment of men and women as actors, directors and writers in the UK theatre industry, and how new writing features in venues’ programming Period 1: 16 – 29 January 2006 (inclusive) Section A: Actors, Writers, Directors and New Writing. For the two weeks covered in Period 1, there were 140 productions staged at 112 venues. Writers Of the 140 productions there were: 98 written by men 70% 13 written by women 9% 22 mixed collaboration 16% (7 unknown) 5% New Writing 48 of the 140 plays were new writing (34%). Of the 48 new plays: 30 written by men 62% 8 written by women 17% 10 mixed collaboration 21% The greatest volume of new writing was shown at Fringe venues, with 31% of its programme for the specified time period featuring new writing. New Adaptations/ New Translations 9 of the 140 plays were new adaptations/ new translations (6%). Of the 9 new adaptations/ new translations: 5 written by men 0 written by women 4 mixed collaboration 2 WOMEN IN THEATRE 2006 SURVEY Sphinx Theatre Company copyright 2006. No part of this survey may be reproduced without permission Directors 97 male directors 69% 32 female directors 23% 6 mixed collaborations 4% (5 unknown) 4% Fringe theatres employed the most female directors (9 or 32% of Fringe directors were female), while subsidised west end venues employed the highest proportion of female directors (8 or 36% were female). -

GILBERT and SULLIVAN PAMPHLETS† Number Two

1 GILBERT AND SULLIVAN PAMPHLETS † Number Two CURTAIN RAISERS A Compilation by Michael Walters and George Low First published October 1990 Slightly revised edition May 1996 Reprinted May 1998. Reformatted and repaginated, but not otherwise altered. INTRODUCTION Very little information is available on the non Gilbert and Sullivan curtain raisers and other companion pieces used at the Savoy and by the D’Oyly Carte Opera Company on tour in their early years. Rollins and Witts give a brief list at the back of their compilation, and there are passing references to some of the pieces by Adair-Fitz- gerald and others. This pamphlet is intended to give some more data which may be of use and interest to the G&S fraternity. It is not intended to be the last word on the subject, but rather the first, and it is hoped that it will provoke further investigation. Perhaps it may inspire others to make exhaustive searches in libraries for the missing scores and libretti. Sources: Cyril Rollins & R. John Witts: 1962. The D’Oyly Carte Opera Company in Gilbert and Sullivan Operas. Cyril Rollins & R. John Witts: 1971. The D’Oyly Carte Opera Company in Gilbert and Sullivan Operas. Second Supplement. Privately printed. p. 19. J.P. Wearing: 1976. The London Stage, 1890-1899. 2 vols. J.P. Wearing: 1981. The London Stage, 1900-1909. 2 vols. Allardyce Nicoll: A History of English Drama 1660-1900, vol. 5. (1959) Late Nineteenth Century Drama 1850-1900. Kurt Ganzl: 1986. The British Musical Theatre. 2 vols. S.J. Adair-Fitzgerald: 1924. -

What's on Guide | Cultural Events

What’s On Guide | Cultural Events December Janurary 2019 Star Wars: A New Hope in Concert, Manchester - 1st Dec The Nutcracker, Royal Opera House - 3rd Dec - 15th Jan Madonna, O2 Arena - 1st & 2nd Dec Hogwarts in the Snow, Warner Bros. - 17th Nov - 27th Jan Frankie Valli and The Four Seasons, O2 Arena - 2nd Dec Chicago, Phoenix Theatre - Available Until 5th Jan Love Actually, Royal Drury Lane - 2nd Dec Disney On Ice, O2 Arena - 26th Dec - 6th Jan Swan Lake, Sadler's Wells - 4th Dec 2018 - 27th Jan 2019 London Short Film Festival, London - 11th - 20th Jan Years & Years, O2 Arena - 5th Dec The Queen of Spades, Royal Opera House - 13th Jan Def Leppard, O2 Arena - 6th Dec La Traviata, Royal Opera House - 14th Jan Snow White, Palladium - 8th Dec 2018 - 13th Jan 2019 Cirque du Soleil, Royal Albert Hall - 12th Jan- 9th Feb Mariah Carey, O2 Arena - 11th Dec The 1975, O2 Arena - 18th & 19th Jan British Fashion Awards, Royal Albert Hall - 10th Dec The Streets, Birmingham O2 Academy - 19th Jan The Nutcracker, London Coliseum, 13th - 30th Dec Strictly Come Dancing, Birmingham Arena - 19th & 20th Jan Horrible Christmas, Alexandra Palace - 13th - 30th Dec National Television Awards, O2 Arena - 22nd Jan Paul McCartney, O2 Arena - 16th Dec Strictly Come Dancing, Leeds Arena - 25th Jan Christmas Spectacular, London Palladium - 16th - 23rd Dec Strictly Come Dancing, Manchester Arena - 26th & 27th Jan The Snowman Live in Concert, Royal Albert Hall - 20th Dec Snow Patrol, O2 Arena - 26th Jan Handel’s Messiah, Royal Albert Hall - 21st Dec 9 to 5 - The Musical, -

Open a PDF List of This Collection

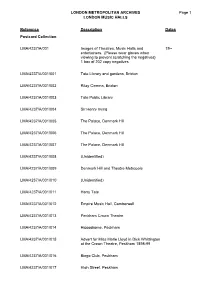

LONDON METROPOLITAN ARCHIVES Page 1 LONDON MUSIC HALLS LMA/4237 Reference Description Dates Postcard Collection LMA/4237/A/001 Images of Theatres, Music Halls and 19-- entertainers. {Please wear gloves when viewing to prevent scratching the negatives} 1 box of 202 copy negatives LMA/4237/A/001/001 Tate Library and gardens, Brixton LMA/4237/A/001/002 Ritzy Cinema, Brixton LMA/4237/A/001/003 Tate Public Library LMA/4237/A/001/004 Sir Henry Irving LMA/4237/A/001/005 The Palace, Denmark Hill LMA/4237/A/001/006 The Palace, Denmark Hill LMA/4237/A/001/007 The Palace, Denmark Hill LMA/4237/A/001/008 (Unidentified) LMA/4237/A/001/009 Denmark Hill and Theatre Metropole LMA/4237/A/001/010 (Unidentified) LMA/4237/A/001/011 Harry Tate LMA/4237/A/001/012 Empire Music Hall, Camberwell LMA/4237/A/001/013 Peckham Crown Theatre LMA/4237/A/001/014 Hippodrome, Peckham LMA/4237/A/001/015 Advert for Miss Marie Lloyd in Dick Whittington at the Crown Theatre, Peckham 1898-99 LMA/4237/A/001/016 Bingo Club, Peckham LMA/4237/A/001/017 High Street, Peckham LONDON METROPOLITAN ARCHIVES Page 2 LONDON MUSIC HALLS LMA/4237 Reference Description Dates LMA/4237/A/001/018 Empire, New Cross Road LMA/4237/A/001/019 Empire, New Cross Road LMA/4237/A/001/020 (Unidentified) LMA/4237/A/001/021 (Unidentified) LMA/4237/A/001/022 Broadway Theatre, Deptford LMA/4237/A/001/023 Miss Kitty Colyer as Cinderella at The Broadway Theatre, Deptford LMA/4237/A/001/024 Broadway Theatre, Deptford LMA/4237/A/001/025 Broadway Theatre, Deptford LMA/4237/A/001/026 Wellington Street, Woolwich LMA/4237/A/001/027 Wellington Street and Town Hall, Woolwich LMA/4237/A/001/028 Town Hall and Hippodrome, Woolwich LMA/4237/A/001/029 Grand Theatre, Woolwich LMA/4237/A/001/030 Grand Theatre, Woolwich LMA/4237/A/001/031 Hippodrome and Brownhill Road, Catford LMA/4237/A/001/032 Hippodrome and Brownhill Road, Catford LMA/4237/A/001/033 Lewisham LMA/4237/A/001/034 Eros House LMA/4237/A/001/035 Poster for 'Lady of Ostend' LMA/4237/A/001/036 Production of 'The Hon. -

© in This Web Service Cambridge University

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-49709-2 - The Cambridge History of British Theatre: Volume 3: Since 1895 Edited by Baz Kershaw Index More information Index Note: Italicised page numbers refer to illustrations. Abbey Theatre, 24, 69, 198, 201 ACW(Arts Council of Wales), 486–9 Abbey Theatre Company, 53 adaptations, 435 ABCA (Army Bureau of Current Affairs), 294, Adding Machine, The, 132 352–3 Adelphi Players, 354 Abraham Lincoln, 158 Admirable Crichton, The, 43, 72 ABSA (Association for Business Sponsorship Adult Education Committee (1926), 133–4 of the Arts), 348, 381 Adwaith, 268 Abse, Dannie, 244 afterpieces, 98, 99 Absence of War, The, 319, 419 After the Orgy, Absent Friends, 310 Agate, James, 45, 116, 131, 148, 157 absurd, theatre of, 337–40, 372 Age of Empire, 58–9 Absurd Person Singular, 345 Age Exchange, 369 Accidental Death of an Anarchist, 310 agitational propaganda (agit prop), 26, Achurch, Janet, 170 176–9 Ac Eto Nid Myfi, 258 Alabama Minstrels, 100 Acis and Galatea, 17 Albert, Prince, 4 Ackland, Rodney, 166 Albery, Bronson, 149 Act of Union, 197 Albery, Donald, 302 Actor and the Uber-Marionette,¨ the, 190 Albery, Ian, 310 actor-manager system, 5–6 Aldwych Theatre, 149, 335 decline of, 11 Alexander, George, 7 historical views of, 6 as actor-manager, 38, 39 and rise in social position of performers, 7 knighthood of, 37 actors, 382–3 repertoire, 65 contracts, 387 as society actor, 8 control of Shakespearean productions, 31–2 success in provincial theatres, 63, 66 earnings, 387 Alexander Marsh Company, 66 employment, 386–7 -

Principal Sources Consulted

Principal Sources Consulted Archival Harold Pinter Archive, British Library. Add. Ms 88880 (see British Library website: www.bl.uk). Printed Baker, William, Harold Pinter (London: Continuum, 2008). Baker, William and John C. Ross, Harold Pinter: A Bibliographical History (London: British Library and New Castle, DE: Oak Knoll Press, 2005). Baker, William and Stephen Ely Tabachnick, Harold Pinter (Edinburgh: Oliver & Boyd, 1973). Bakewell, Joan, The Centre of the Bed (London: Hodder & Stoughton, 2003). Billington, Michael, Harold Pinter, rev. edn (London: Faber, 2007). —— ‘Pinter, Harold (1930–2008)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, Jan 2012, www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/100647. Codron, Michael and Alan Strachan, Putting It On: The West End Theatre of Michael Codron (London: Duckworth Overlook, 2010). Coleman, Terry, Olivier (London: Bloomsbury, 2005). Esslin, Martin, Pinter the Playwright (London: Methuen, 1982). Fay, Stephen, Power Play: The Life and Times of Peter Hall (London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1995). Fraser, Antonia, Must You Go?: My Life with Harold Pinter (London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2010). Gale, Steven H. (ed.), The Films of Harold Pinter (Albany: State University of New York Press, 2001). —— Sharp Cut: Harold Pinter’s Screenplays and the Artistic Process (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2003). Gale, Steven H. and Christopher Hudgins, ‘The Harold Pinter Archives II: A Des- cription of the Filmscript Materials in the Archive in the British Library’, The Pinter Review: Annual Essays 1995 and 1996, ed. Francis Gillen and Steven H. Gale (University of Tampa Press, 1997), 101–42. Gillen, Francis and Steven H. Gale (eds), The Pinter Review: Annual Essays (University of Tampa Press, 1987–2011). -

Download A4 Printable Version

Welcome to Piaf In 1980, Nottingham Playhouse was one of the first theatres to produce Pam Gems’ sensational play and an emerging new talent starred in the titular role – a young Imelda Staunton. Now, 40 years on, we are thrilled to bring Piaf back to our stage, in partnership with Leeds Playhouse. This emotionally-charged play explores the challenging and fascinating life and relationships of the enigmatic Edith Piaf with one of the West End’s leading performers, Jenna Russell, bringing this iconic character to life. Supported by a first-rate company, including some familiar Playhouse faces, our cast and creative team will truly transport you to the streets of Paris this summer. Whether you are joining us at the theatre, or watching our livestream from home, we are so pleased to finally welcome you back for this long-awaited production. It has been a difficult year, but the support of our audiences and friends has been overwhelming. We hope you enjoy the show as much as we have creating it. Stephanie Sirr Adam Penford Chief Executive Artistic Director Fri 29 Oct – Sat 20 Nov 2021 Mark Gatiss (The Madness of George III) stars in his own retelling of Dickens’ classic winter ghost story. It’s Christmas Eve. As the cold, bleak night draws in, the avaricious Ebenezer Scrooge is confronted by the spirit of his former business partner Jacob Marley. Bound in chains as punishment for a lifetime of greed, the unearthly figure explains it isn’t too late for Scrooge to change his miserly ways in order to escape the same fate, but first he’ll have to face three more eerie encounters… Staying true to the heart and spirit of the original novel, this production is filled with Dickensian, spine-tingling special effects; are you brave enough to join us? AN interview with jenna RUSSELL What was your introduction to theatre and when did you know you wanted to be an actor? My earliest memory of going to the theatre was when Mum took me to see Robert Lindsey in Hamlet. -

London Theatre Brochure

LONDON THEATRE BROCHURE MP_Essential-West-End_150x150_AW.indd 1 29/05/2019 11:41 MOUSE18_Q3_22 Encore Essential Assets_Prod Shots_150x150mm.indd 1 14/09/2018 10:59 ESSENTIAL WEST END: USA AND CANADA WELCOME TO LONDON’S WEST END – AN EXPERIENCE LIKE NO OTHER No visit to London is complete without seeing a West End Show. Simplyitickets gives you, the travel trade, a simple way to add the best shows to any FIT, group or package program. We negotiate special rates for all our Trade partners and are able to offer flexible booking conditions and solutions. Our friendly, knowledgeable team members will keep you up to date with information on pricing, schedules and ticket availability. You can book through our 7 days a week call centre, and our B2B booking portal. This booklet showcases Simplyitickets's Essential West End, a group of shows that are simply the best that London’s West End has to offer. These distinctive, world-class performances are sure to enthrall your clients and will be a highlight of their trip. Our aim is to give you all of the tools and information you need to help sell tickets for these shows to your customers before © Disney they travel, ensuring they have the best experience possible. We look forward to welcoming you and your customers to the West End soon! LK_AUG16_Encore_30x30_Vis_1b.indd08/09/2016 1 16:17 Simplyitickets Telephone 1.855.566.1157 Email [email protected] 3 ESSENTIAL WEST END & JULIET Shaftesbury Theatre 210 Shaftesbury Avenue, London WC2H 8DP Romeo & Juliet final scene. Juliet picks up the dagger and..