Rituals of Grief-1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sanctioning Sexuality in Elementary School Halloween Celebrations by Erica M

ISSI GRADUATE FELLOWS WORKING PAPER SERIES 2011-2012.60 Education in Disguise: Sanctioning Sexuality in Elementary School Halloween Celebrations by Erica M. Boas Graduate School of Education University of California, Berkeley October 19, 2012 Erica M. Boas Graduate School of Education University of California at Berkeley [email protected] Given the pervasive silence that surrounds sexuality in elementary schools, Halloween provides a rare opportunity to explore its tangible manifestations. Schools sanction overt displays of sexuality and transgressions of certain school norms on this day. A time of celebration, it is perceived as a festive event for children, innocent and fun. Yet, because Halloween is the one school day where sexuality is on display, sexuality literally becomes a spectacle. Halloween serves as a magnifying glass to examine the operation of sexuality in the institution of elementary schools, illuminating a nexus of attendant relationships—social, economic, political, and cultural. These relationships lie buried beneath the veneer of fun and play that is popularly imagined as integral to the holiday. Drawing from ethnographic data collected over the 2010-2011 school year, I explore how processes of citizen creation through schooling are abetted by the U.S. consumer market, which strategically targets children, and girls in particular. This paper examines the ways in which elementary school Halloween celebrations bring to light the significance of sexuality in a culture that creates and exploits children’s desires. The Institute for the Study of Societal Issues (ISSI) is an Organized Research Unit of the University of California at Berkeley. The views expressed in working papers are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent those of the ISSC or the Regents of the University of California. -

American Halloween: Enculturation, Myths and Consumer Culture

American Halloween: Enculturation, Myths and Consumer Culture Shabnam Yousaf Quaid I Azam University Islamabad, Pakistan Abstract The cultish festival of Halloween is encultured through mythology and has become a hybrid consumer culture in the American society. Historiographical evidences illustrate that how it was being Christianized in the 9th century CE and transformed a Pagan Northern-European religious tradition from its adaptation to the enculturation process by the early church, to remember the dead in tricking and treating manners. This paper will illuminate the intricate medieval history of Celtic origins of Halloween, etymology of Samhain festival, rites of passages and the religious rituals practicing in America regarding Halloween that how it evolved from paganism to Neo-paganism and hybridized through materialist glorification from mythology to consumer culture. The mid of 19th century witnessed the arrival of Samhain rituals in America with the displacement of Irish population. Presently, this festival is infused with the folk traditions and carnivals. The trajectory penetrates its roots from discourse to practical implications, incorporated in American culture and became materialized. To assess and analyze the concoction of mythology, enculturation into culturally materialized form and developed into a consumer culture, This paper will take the assistance from Marvin Harris ‘Cultural Materialism’, to seek the behavioral and mental superstructure of the American social fabric for operationalizing the connections and to determine the way forward to explore the rhetorical fabricated glorification of consumer culture inculcated through late-capitalism, will be assessed by Theodore Adorno’s theoretical grounds of ‘The Culture Industry’. This article will re-orientate and enlighten the facts and evolving processes practicing in the American society and inquire that how the centuries old mythologies are being encultured and amalgamated with the socio-cultural, religious and economic interests. -

Annual Index: V.99 ! 1

Booklist / September 1, 2002 through August 2003 Annual Index: v.99 ! 1 Adler, David A. A Picture Book of Harriet Beecher Air Warfare. 618. ANNUAL INDEX: VOLUME 99: Stowe. 1800. Airborne. Collins. 994. Adler, David A. A Picture Book of Lewis and Clark. Airborne. Flanagan. 551. 1066. Aird, Catherine. Amendment of Life. 854. SEPT. 1, 2002–AUGUST 2003 Adler, David A. Young Cam Jansen and the Zoo Aitken, Rosemary. The Granite Cliffs. 1383. Note Mystery. 1530. Aizley, Harlyn. Buying Dad. 1715. This cumulative index includes entries under author, title, and illus- Adler, Naomi. The Barefoot Book of Animal Tales. Ajmera, Maya. A Kid's Best Friend. 134. trator (for children’s books). Bibliographies are listed individually 894. Akbar, M. J. The Shade of Swords. 182. Adler, Sabine. Lovers in Art. 191. Akiko and the Alpha Centauri 5000. Crilley. 1660. by title, but they also appear here under the heading Bibliographies, The Admiral's Daughter. Madden. 1452. Akunin, Boris. The Winter Queen. 1637. Special Lists, and Features. Media reviews are indexed separately. Adoff, Jaime. The Song Shoots out of My Mouth. Al on America. Sharpton. 384. 864. Al Williamson Adventures. 1855. Adolescent Health Sourcebook. 264. ALA'S 2003 "BEST" LISTS. 1288. 1,000 Inventions and Discoveries. Bridgman. 620. Abodehman, Ahmed. The Belt. 53. Adolf Hitler. Nardo. 868. Alabanza. Espada. 1366. 1-2-3 Draw Cartoon Animals. Barr. 872. Abou el Fadl, Khaled. The Place of Tolerance in Is- Adrahtas, Tom. Glenn Hall. 1364. Alagna, Magdalena. Life inside the Air Force Acad- 1-2-3 Draw Cartoon Faces. Barr. 872. lam. 365. -

Table of Contents

Provided by the author(s) and NUI Galway in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite the published version when available. Title Thanatourism and the commodification of war tourism space in ex-Yugoslavia Author(s) Johnston, Anthony Publication Date 2011-09-20 Item record http://hdl.handle.net/10379/2288 Downloaded 2021-09-28T00:11:42Z Some rights reserved. For more information, please see the item record link above. Thanatourism and the commodification of war tourism space in ex-Yugoslavia Anthony Patrick Johnston Supervised by Professor Ulf Strohmayer School of Geography & Archaeology Department of Geography, National University of Ireland, Galway May 2011 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ABSTRACT……………………………………………………………… I ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS……………………………………………… III LIST OF IMAGES……………………………………………………….. IV LIST OF FIGURES……………………………………………………… VI PROLOGUE…………………………………………………………….. VII Chapter 1: Introduction 1 1.1 Research background……………………………………… 2 1.2 Thanatourism in geography…………………….…………. 7 1.3 Why study thanatourism in ex-Yugoslavia……………….. 10 1.4 A background to thanatourism in ex-Yugoslavia.………… 17 1.5 Research objectives…………………………….………….. 19 1.6 Outline of forthcoming chapters……………….…………... 21 Chapter 2: Contextualising Thanatourism 23 2.1 Introduction…………………………………………………. 24 2.2 Postmodernism in the geography of tourism ………………. 28 2.3 Secularisation and new moral spaces……………………….. 48 2.4 Thanatopsis and a sociology of death….…………..……….. 51 2.5 Orientalism………………………………………………….. 71 2.6 Conclusion…………………………………………………… 75 Chapter 3: Situating Thanatourism 80 3.1 Introduction………………………………………………….... 81 3.2 New horizons in tourism & niche tourism………….………… 84 3.3 Typologies of thanatourism…………………………………… 87 3.4 Recent explorations of thanatourism…………………………. 95 3.5 Commodification of death ……………………………………. 100 3.6 Guides, entrepreneurs and mediating heritage………………... 105 3.7 Motivations and experiences………………………………….. 109 3.8 Inveraray Jail Case Study…………………………………….. -

Devils-Night-11-Black-Cover

THE DEVIL’S NIGHT ON THE UNGOVERNABLE SPIRIT OF HALLOWEEN New Orleans, Mischief Night 2016 We had no words to give weight and form to the feeling of cool October nights in Detroit. After we smashed the winking eyes of streetlights the dark on the streets pressed its body close and wrapped its cloak around us; and we could not speak. We had no words dark enough for the Devil’s Night moon – fat, full, and silver – that we could not smash. It shined white on us as we crept between hedges and houses, crawled onto roofs, and dashed through alleys. It slashed at our heels as we hopped rattly, metal fences silently as alley cats. We had no words for these: the feel of dark the moon weaving silver onto the metal webs of city fences the ships screaming into the mouth of the Rouge River, and the lights of tall buildings blinking through the stinging smoke of a burning Detroit. Carmen Lowe The Metaphysics of Vandalism (1989) Morton, Lisa. Trick or Treat: A History of Halloween. Reaktion Books, 2012. Muraro, Luisa. La Signora del Gioco: Episodi di cacda alle streghe. Feltrinelli Editore, 1977. Nagengast, Carole. Violence, Terror, and the Crisis of the State. Annual Review of THE Anthropology, Vol. 23, 1994. DEVIL’S Rogers, Nicholas. Halloween: From Pagan Ritual to Party Night. Oxford Univer- sity Press, 2002. NIGHT ONTHEUNGOVERNABLE Skal, David. Death Makes a Holiday: A Cultural History of Halloween. Blooms- SPIRITOF HALLOWEEN bury, 2002. Stahl, Kenneth. “Snipers.” Detroit’s Great Rebellion. http://www.de- troits-great-rebellion.com/Snipers.html. -

Performing Halloween in the Netherlands John Helsloot

THE FUN OF FEAR: PERFORMING HALLOWEEN IN THE NETHERLANDS JOHN HELSLOOT During the last five years-since the 9111 attacks in particular preventing the spread of fear may be said to have permeated the whole fabric of Western societies, if not of the globe at large. And when disaster does occur, one of the means of redressing the emotional balance in society is through ritual (Post et al. 2003; Stengs 2003; Santino 2006). It may come as a surprise, then, to find a ritual like Halloween being celebrated, given that to all intents and purposes it is designed to provoke fear, terror and horror. Of course, to this it might reasonably be objected that Halloween and terrorism are utterly unrelated and incomparable phenomena-see, however, Skal (2002, 184), who mentions a Halloween "Fright House" in Washington featuring "apocalyptic images of the destruction of the U.S. capitol, the Pentagon, and the White House"-and besides, that the history of Halloween clearly precedes 9/11. Such a swift dismissal, however, would in an untimely way preclude an exploration of the possible relationships between the fun of fear and wider social and cultural issues. In undertaking such an analysis, I draw my perspective from a combination of historical and anthropological theories on understanding ritual-taking as a shorthand definition that ritual is "a sign language of the emotions" ("eine Zeichensprache der Affekte", Scharfe 1999, 162)-in contemporary Western society, focusing on the Netherlands as my case study. Catherine Bell and others (e.g. Burckhardt-Seebass 1989, 99-100; Eriksen 1994; Frykman and LOfgren 1996, 19) have argued, convincingly in my view, that in late 20th century society attitudes towards ritual have changed radically. -

SPIRALINEAR TIME: RELIGIOUS CALENDAR FORMATION, MOMENTUM, and CHANGE WITHIN a DYNAMIC TIME STRUCTURE by SARAH EMILY RICHARDS

SPIRALINEAR TIME: RELIGIOUS CALENDAR FORMATION, MOMENTUM, AND CHANGE WITHIN A DYNAMIC TIME STRUCTURE by SARAH EMILY RICHARDS (Under the Direction of Carolyn Jones Medine) ABSTRACT This work explores the reciprocal relationship between sacred time as manifest in religious calendars and their parent religious traditions. The primary purpose of the work is to introduce a new conceptual tool for diagramming and studying the functions and effects of recurring religious holidays and rituals. This conceptual tool is called “spiralinear time,” and it combines several of the traditional dualities assigned to concepts of time such as linear versus cyclical. The spiralinear time concept is built upon observation of several calendar traditions of Western civilization as well as major theories of time in the study of religion. This thesis will also defend the idea of co- development and co-genesis between a given religion and its associated calendar, rather than viewing the calendar as a direct product of its religion. It will show that calendars are thus one of the most effective tools in the purpose-driven evolution of religion, as well as one of the most interesting products thereof. INDEX WORDS: sacred time, religious calendar, liturgical year, Hebrew calendar, harvest festival, ritual time, seasonal festival, intercalation, Thanksgiving, Halloween, time line, lunisolar, cyclical time SPIRALINEAR TIME: RELIGIOUS CALENDAR FORMATION, MOMENTUM, AND CHANGE WITHIN A DYNAMIC TIME STRUCTURE by SARAH EMILY RICHARDS B.A., Emory University, 2000 A Thesis -

Devils-Night-11-Black-Cover.Pdf

We had no words to give weight and form to the feeling of cool October nights in Detroit. After we smashed the winking eyes of streetlights the dark on the streets pressed its body close and wrapped its cloak around us; and we could not speak. We had no words dark enough for the Devil’s Night moon – fat, full, and silver – that we could not smash. It shined white on us as we crept between hedges and houses, crawled onto roofs, and dashed through alleys. It slashed at our heels as we hopped rattly, metal fences silently as alley cats. We had no words for these: the feel of dark the moon weaving silver onto the metal webs of city fences the ships screaming into the mouth of the Rouge River, and the lights of tall buildings blinking through the stinging smoke of a burning Detroit. Carmen Lowe The Metaphysics of Vandalism (1989) Morton, Lisa. Trick or Treat: A History of Halloween. Reaktion Books, 2012. Muraro, Luisa. La Signora del Gioco: Episodi di cacda alle streghe. Feltrinelli Editore, 1977. Nagengast, Carole. Violence, Terror, and the Crisis of the State. Annual Review of Anthropology, Vol. 23, 1994. Rogers, Nicholas. Halloween: From Pagan Ritual to Party Night. Oxford Univer- sity Press, 2002. Skal, David. Death Makes a Holiday: A Cultural History of Halloween. Blooms- bury, 2002. Stahl, Kenneth. “Snipers.” Detroit’s Great Rebellion. http://www.de- troits-great-rebellion.com/Snipers.html. Stubbs, Phillip. The Anatomie of Abuses. 1583. Thompson, Paul. The War with Adults. Oral History Vol. 2, No. 2, Family His- tory Issue, 1975. -

Albertmohler.Com – Christianity and the Dark Side: What About Halloween?

http://www.albertmohler.com/2003/10/31/christianity-and-the-dark-side-what-about-halloween-3/ 1/3 AlbertMohler.com Christianity and the Dark Side: What About Halloween? Over a hundred years ago, the great Dutch theologian Hermann Bavinck predicted that the 20th century would “witness a gigantic conflict of spirits.” His prediction turned out to be an understatement, and this great conflict continues into the 21st century. Friday, October 31, 2003 Over a hundred years ago, the great Dutch theologian Hermann Bavinck predicted that the 20th century would “witness a gigantic conflict of spirits.” His prediction turned out to be an understatement, and this great conflict continues into the 21st century. The issue of Halloween presses itself annually upon the Christian conscience. Acutely aware of dangers new and old, many Christian parents choose to withdraw their children from the holiday altogether. Others choose to follow a strategic battle plan for engagement with the holiday. Still others have gone further, seeking to convert Halloween into an evangelistic opportunity. Is Halloween really that significant? Well, Halloween is a big deal in the marketplace. Halloween is surpassed only by Christmas in terms of economic activity. According to David J. Skal, “Precise figures are difficult to determine, but the annual economic impact of Halloween is now somewhere between 4 billion and 6 billion dollars depending on the number and kinds of industries one includes in the calculations.” Furthermore, historian Nicholas Rogers claims that “Halloween is currently the second most important party night in North America. In terms of its retail potential, it is second only to Christmas. -

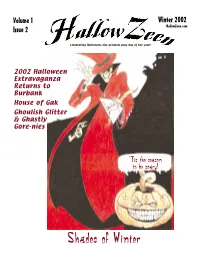

Hallowzeen Vol 1, Issue 2

Volume 1 Winter 2002 Issue 2 HallowZeen.com Celebrating Halloween—the greatest play day of the year! 2002 Halloween Extravaganza Returns to Burbank House of Gak Ghoulish Glitter & Ghastly Gore-nies ‘Tis the season to be scary! ShadesS of WinterW Volume 1, Issue 2 Winter 2002 Editor’s Celebrating Halloween—the greatest play day of the year! 3 House of Gak Column by Dusti Lewars-Poole 5 Magic + Halloween = David Parr 6 Little Bernice by Jo Gray 7 We Wish You’d Quit Trick-or-Treating by David R. Lady Ghoultide greetings as we bring you the second issue of 10 Pumpkin Hall of Horrors HallowZeen! Our premiere issue proved very popular with 4,000 by Dennis Baum downloads to date—and counting. In this issue we bring you more 11 Ghoulish Glitter and Ghastly Gore-nies news on Halloween happenings that are sure to help brighten your by Tom Geil spirits as we face the prospect of a long, and for some of us a very 12 Little Bernice cold, winter. by Jo Gray Here you’ll find solace from the doldrums of winter in a variety of 13 Book Reviews interesting stories on Halloween. We begin with a fascinating profile Ghost Dogs of the South of three haunts in Pennsylvania which our own Queen of Quirk, Dusti Death Makes a Holiday Lewars-Poole, terms “House of Gak.” Not familiar with the term? Me 14 2002 Halloween Extravaganza Returns neither but go to page 3 and you, too, will be enlightened. to Burbank by John Pearson Two years ago I saw magician David Parr perform a show at Halloween in Milwaukee and was mesmerized. -

Hollands Maandblad. Jaargang 2005 (686-697)

Hollands Maandblad. Jaargang 2005 (686-697) bron Hollands Maandblad. Jaargang 2005 (686-697). L.J. Veen, Amsterdam 2005 Zie voor verantwoording: https://www.dbnl.org/tekst/_hol006200501_01/colofon.php Let op: werken die korter dan 140 jaar geleden verschenen zijn, kunnen auteursrechtelijk beschermd zijn. i.s.m. binnenkant voorplat [686] [Medewerkers] THOMAS BERSEE - geboren in 1957. Historicus, thans werkzaam als onderwijsadviseur bij het Centrum voor Innovatie van Opleidingen (CINOP). Winnaar van de Hollands Maandblad Schrijversbeurs 2003-2004 (Essayistiek) voor zijn eerdere publicaties in Hollands Maandblad. WANDA BOMMER - geboren in 1969. Werkzaam als boeker van popgroep ‘De Dijk’. Tevens tweedejaars proza- en scenariostudent aan de Schrijversvakschool Amsterdam (voorheen 't Colofon). Maakt in dit Hollands Maandblad haar prozadebuut. EMMA CREBOLDER - geboren in 1942. Afrikaniste. Recente poëziebundels van haar hand zijn Zand-orakel (1994), Zwerftaal (1995), Dansen met een vos (1998) en Golf (2003). COR GORDIJN - geboren in 1969. Studeerde Nederlands, Frans en filosofie; thans werkzaam als docent Frans en filosofie aan een gymnasium te Den Haag. Winnaar van de Hollands Maandblad Schrijversbeurs 2002-2003 (Poëzie) voor zijn eerdere publicaties in Hollands Maandblad. TANJA KARREMAN - geboren in 1966. Kunsthistorica, werkt als freelance ‘adviseur kunst en het publieke domein’, tot voor kort voor het Amsterdamse Fonds voor de Kunst, en publiceert regelmatig over het onderwerp. MARGRIET DE KONING GANS - geboren in 1942. Studeerde Nederlands en Algemene Literatuurwetenschap te Leiden. Was werkzaam in het voortgezet onderwijs, als redactrice, en als galeriehoudster te Amsterdam. Publiceerde eerder in Hollands Maandblad. MARGERITE LUITWIELER - geboren in 1960. Beeldend kunstenaar en dichter. Freelance docent bij Centrum voor Beeld en Cultuur MK24 te Amsterdam in o.a. -

Halloween - Reckoning the Season

Halloween - Reckoning the Season ! Halloween has taken Australia by storm. Walk into a popular shopping centre and you are assaulted by an overwhelming array of Halloween merchandise in the form of witches, monsters, and all sorts of spooky paraphernalia. Oh that one of the Hebrew holidays would receive such a revival in this dry and barren land! But let’s be perfectly honest here. The human psyche is geared to like a good story and the more thrills and spills it has, the more it captivates our imaginations. Scripture alone attests to this, being filled with harrowing tales, often not ended well. 1 ! Before we examine Halloween, let’s clear a few things up regarding the natural human need to experience fear. Why do people chase fear and is it healthy? The answer is yes, human beings have an in-built desire to fear. Fear preserves life; it’s the thing that stops us from jumping off a cliff, speaking inappropriately or even assaulting someone. Every good fair has a haunted house attraction. Why? Because being scared exhilarates people and reminds them that life is good. That’s why for the first five minutes after riding a roller-coaster, everyone is jumping up and down like chickens and then they gradually calm down and return to normal. Fear enables a believer to calculate their true spiritual standing before the Almighty, causing them to avoid being conceited, puffed- up or narcissistic. Fear switches on every awareness button you have. (Slide) “Therefore, my dear friends, as you have always obeyed--not only in my presence, but now much more in my absence--continue to work out your salvation with fear and trembling.” (Philippians 2:12) 2 “I will tell you, my friends, do not be afraid of those who kill the body and after that can do no more.