Linguistic Complexity: What Do Albanian Dialects Show?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Onomastics – Using Naming Patterns in Genealogy

Onomastics – Using Naming Patterns in Genealogy 1. Where did your family live before coming to America? 2. When did your family come to America? 3. Where did your family first settle in America? Background Onomastics or onomatology is the study of proper names of all kinds and the origins of names. Toponomy or toponomastics, is the study of place names. Anthroponomastics is the study of personal names. Names were originally used to identify characteristics of a person. Over time, some of those original meanings have been lost. Additionally, patterns developed in many cultures to further identify a person and to carry on names within families. In genealogy, knowing the naming patterns of a cultural or regional group can lead to breaking down brick walls. Your great-great-grandfather’s middle name might be his mother’s maiden name – a possible clue – depending on the naming patterns used in that time and place. Of course, as with any clues, you need to find documents to back up your guesses, but the clues may lead you in the right direction. Patronymics Surnames based on the name of the father, such as Johnson and Nielson, are called patronyms. Historically people only had one name, but as the population of an area grew, more was needed. Many cultures used patronyms, with every generation having a different “last name.” John, the son of William, would be John Williamson. His son, Peter, would be Peter Johnson; Peter’s son William would be William Peterson. Patronyms were found in places such as Scandinavia (sen/dottir), Scotland Mac/Nic), Ireland (O’/Mac/ni), Wales (ap/verch), England (Fitz), Spain (ez), Portugal (es), Italy (di/d’/de), France (de/des/du/le/à/fitz), Germany (sen/sohn/witz), the Netherlands (se/sen/zoon/dochter), Russia (vich/ovna/yevna/ochna), Poland (wicz/wski/wsky/icki/-a), and in cultures using the Hebrew (ben/bat) and Arabic (ibn/bint) languages. -

IMES Alumni Newsletter No.8

IMES ALUMNI NEWSLETTER Souk at Fez, Morocco Issue 8, Winter 2016 8, Winter Issue © Andrew Meehan From the Head of IMES Dr Andrew Marsham Welcome to the Winter 2016 IMES Alumni Newsletter, in which we congrat- ulate the postgraduate Masters and PhD graduates who qualified this year. There is more from graduation day on pages 3-5. We wish all our graduates the very best for the future. We bid farewell to Dr Richard Todd, who has taught at IMES since 2006. Richard was a key colleague in the MA Arabic degree, and has contributed to countless other aspects of IMES life. We wish him the very best for his new post at the University of Birmingham. Memories of Richard at IMES can be found on page 17. Elsewhere, there are the regular features about IMES events, as well as articles on NGO work in Beirut, on the SkatePal charity, poems to Syria, on recent workshops on masculinities and on Arab Jews, and memories of Arabic at Edinburgh in the late 1960s and early 1970s from Professor Miriam Cooke (MA Arabic 1971). Very many thanks to Katy Gregory, Assistant Editor, and thanks to all our contributors. As ever, we all look forward to hearing news from former students and colleagues—please do get in touch at [email protected] 1 CONTENTS Atlas Mountains near Marrakesh © Andrew Meehan Issue no. 8 Snapshots 3 IMES Graduates November 2016 6 Staff News Editor 7 Obituary: Abdallah Salih Al-‘Uthaymin Dr Andrew Marsham Features 8 Student Experience: NGO Work in Beirut Assistant Editor and Designer 9 Memories of Arabic at Edinburgh 10 Poems to Syria Katy Gregory Seminars, Conferences and Events 11 IMES Autumn Seminar Review 2016 With thanks to all our contributors 12 IMES Spring Seminar Series 2017 13 Constructing Masculinities in the Middle East The IMES Alumni Newsletter welcomes Symposium 2016 submissions, including news, comments, 14 Arab Jews: Definitions, Histories, Concepts updates and articles. -

International Naming Conventions NAFSA TX State Mtg

1 2 3 4 1. Transcription is a more phonetic interpretation, while transliteration represents the letters exactly 2. Why transcription instead of transliteration? • Some English vowel sounds don’t exist in the other language and vice‐versa • Some English consonant sounds don’t exist in the other language and vice‐versa • Some languages are not written with letters 3. What issues are related to transcription and transliteration? • Lack of consistent rules from some languages or varying sets of rules • Country variation in choice of rules • Country/regional variations in pronunciation • Same name may be transcribed differently even within the same family • More confusing when common or religious names cross over several countries with different scripts (i.e., Mohammad et al) 5 Dark green countries represent those countries where Arabic is the official language. Lighter green represents those countries in which Arabic is either one of several official languages or is a language of everyday usage. Middle East and Central Asia: • Kurdish and Turkmen in Iraq • Farsi (Persian) and Baluchi in Iran • Dari, Pashto and Uzbek in Afghanistan • Uyghur, Kazakh and Kyrgyz in northwest China South Asia: • Urdu, Punjabi, Sindhi, Kashmiri, and Baluchi in Pakistan • Urdu and Kashmiri in India Southeast Asia: • Malay in Burma • Used for religious purposes in Malaysia, Indonesia, southern Thailand, Singapore, and the Philippines Africa: • Bedawi or Beja in Sudan • Hausa in Nigeria • Tamazight and other Berber languages 6 The name Mohamed is an excellent example. The name is literally written as M‐H‐M‐D. However, vowels and pronunciation depend on the region. D and T are interchangeable depending on the region, and the middle “M” is sometimes repeated when transcribed. -

The Albanian Case in Italy

Palaver Palaver 9 (2020), n. 1, 221-250 e-ISSN 2280-4250 DOI 10.1285/i22804250v9i1p221 http://siba-ese.unisalento.it, © 2020 Università del Salento Majlinda Bregasi Università “Hasan Prishtina”, Pristina The socioeconomic role in linguistic and cultural identity preservation – the Albanian case in Italy Abstract In this article, author explores the impact of ever changing social and economic environment in the preservation of cultural and linguistic identity, with a focus on Albanian community in Italy. Comparisons between first major migration of Albanians to Italy in the XV century and most recent ones in the XX, are drawn, with a detailed study on the use and preservation of native language as main identity trait. This comparison presented a unique case study as the descendants of Arbëresh (first Albanian major migration) came in close contact, in a very specific set of circumstances, with modern Albanians. Conclusions in this article are substantiated by the survey of 85 immigrant families throughout Italy. The Albanian language is considered one of the fundamental elements of Albanian identity. It was the foundation for the rise of the national awareness process during Renaissance. But the situation of Albanian language nowadays in Italy among the second-generation immigrants shows us a fragile identity. Keywords: Language identity; national identity; immigrants; Albanian language; assimilation. 221 Majlinda Bregasi 1. An historical glance There are two basic dialect forms of Albanian, Gheg (which is spoken in most of Albania north of the Shkumbin river, as well as in Montenegro, Kosovo, Serbia, and Macedonia), and Tosk, (which is spoken on the south of the Shkumbin river and into Greece, as well as in traditional Albanian diaspora settlements in Italy, Bulgaria, Greece and Ukraine). -

Scottish Naming Customs Craig L

Scottish Naming Customs Craig L. Foster AG® [email protected] Origins of Scottish Surnames Surnames are said to have begun to be used by Scottish nobility at the direction of King Malcolm Ceannmor in about 1061. William L. Kirk, Jr. “Introduction to the Derivation of Scottish Surnames,” Clan Macrae (1992), http://www.clanmacrae.ca/documents/names.htm “In some Highland areas, though, fixed surnames did not become the norm until the 18th century, and in parts of the Northern Isles until the 19th century.” “Surnames,” ScotlandsPeople, https://www.scotlandspeople.gov.uk/guides/surnames Types of Scottish Surnames Location-Based Surnames Some people were named for localities. For example, the surname “Murray from the lands of Moray, and Ogilvie, which, according to Black, derives from the barony of Ogilvie in the parish of Glamis, Angus. Tenants might in turn assume, or be given, the name of their landlord, despite having no kinship with him.” Sometimes surnames referred to a specific topographical feature of the landscape such as a river, a loch, a hill, etc. Some examples might include: Names that contain 'kirk' (as in Kirkland, or Selkirk) which means 'church' in Gaelic; 'Muir' or names that contain it (means 'moor' in Gaelic); A name which has 'Barr' in it (this means 'hilltop' in Gaelic). “Surnames,” ScotlandsPeople, https://www.scotlandspeople.gov.uk/guides/surnames Occupational Surnames A significant amount of surnames come from occupations. So a smith became known as Smith or Gow (Gaelic for smith), a tailor became Tailor/Taylor, a baker was Baxter, a weaver was Webster, etc. “Surnames,”ScotlandsPeople, https://www.scotlandspeople.gov.uk/guides/surnames Descriptive Surnames “Nicknames were 'descriptional' ie. -

Russia's Hostile Measures in Europe

Russia’s Hostile Measures in Europe Understanding the Threat Raphael S. Cohen, Andrew Radin C O R P O R A T I O N For more information on this publication, visit www.rand.org/t/RR1793 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available for this publication. ISBN: 978-1-9774-0077-2 Published by the RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, Calif. © Copyright 2019 RAND Corporation R® is a registered trademark. Limited Print and Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law. This representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for noncommercial use only. Unauthorized posting of this publication online is prohibited. Permission is given to duplicate this document for personal use only, as long as it is unaltered and complete. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of its research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please visit www.rand.org/pubs/permissions. The RAND Corporation is a research organization that develops solutions to public policy challenges to help make communities throughout the world safer and more secure, healthier and more prosperous. RAND is nonprofit, nonpartisan, and committed to the public interest. RAND’s publications do not necessarily reflect the opinions of its research clients and sponsors. Support RAND Make a tax-deductible charitable contribution at www.rand.org/giving/contribute www.rand.org Preface This report is the collaborative and equal effort of the coauthors, who are listed in alphabetical order. The report documents research and analysis conducted through 2017 as part of a project entitled Russia, European Security, and “Measures Short of War,” sponsored by the Office of the Deputy Chief of Staff, G-3/5/7, U.S. -

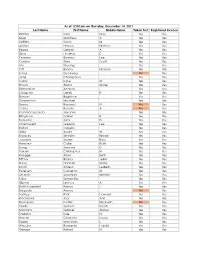

Last Name First Name Middle Name Taken Test Registered License

As of 12:00 am on Thursday, December 14, 2017 Last Name First Name Middle Name Taken Test Registered License Richter Sara May Yes Yes Silver Matthew A Yes Yes Griffiths Stacy M Yes Yes Archer Haylee Nichole Yes Yes Begay Delores A Yes Yes Gray Heather E Yes Yes Pearson Brianna Lee Yes Yes Conlon Tyler Scott Yes Yes Ma Shuang Yes Yes Ott Briana Nichole Yes Yes Liang Guopeng No Yes Jung Chang Gyo Yes Yes Carns Katie M Yes Yes Brooks Alana Marie Yes Yes Richardson Andrew Yes Yes Livingston Derek B Yes Yes Benson Brightstar Yes Yes Gowanlock Michael Yes Yes Denny Racheal N No Yes Crane Beverly A No Yes Paramo Saucedo Jovanny Yes Yes Bringham Darren R Yes Yes Torresdal Jack D Yes Yes Chenoweth Gregory Lee Yes Yes Bolton Isabella Yes Yes Miller Austin W Yes Yes Enriquez Jennifer Benise Yes Yes Jeplawy Joann Rose Yes Yes Harward Callie Ruth Yes Yes Saing Jasmine D Yes Yes Valasin Christopher N Yes Yes Roegge Alissa Beth Yes Yes Tiffany Briana Jekel Yes Yes Davis Hannah Marie Yes Yes Smith Amelia LesBeth Yes Yes Petersen Cameron M Yes Yes Chaplin Jeremiah Whittier Yes Yes Sabo Samantha Yes Yes Gipson Lindsey A Yes Yes Bath-Rosenfeld Robyn J Yes Yes Delgado Alonso No Yes Lackey Rick Howard Yes Yes Brockbank Taci Ann Yes Yes Thompson Kaitlyn Elizabeth No Yes Clarke Joshua Isaiah Yes Yes Montano Gabriel Alonzo Yes Yes England Kyle N Yes Yes Wiman Charlotte Louise Yes Yes Segay Marcinda L Yes Yes Wheeler Benjamin Harold Yes Yes George Robert N Yes Yes Wong Ann Jade Yes Yes Soder Adrienne B Yes Yes Bailey Lydia Noel Yes Yes Linner Tyler Dane Yes Yes -

Song As the Memory of Language in the Arbëresh Community of Chieuti

MY HEART SINGS TO ME: Song as the Memory of Language in the Arbëresh Community of Chieuti Sara Jane Bell A thesis submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Curriculum in Folklore. Chapel Hill 2011 Approved by: Dr. Robert Cantwell (Chair) Dr. William Ferris Dr. Louise Meintjes Dr. Patricia Sawin ABSTRACT SARA JANE BELL: My Heart Sings to Me: Song as the Memory of Language in the Arbëresh Community of Chieuti (Under the Direction of Robert Cantwell, Chair; William Ferris; Louise Meintjes; and Patricia Sawin) For the people of Chieuti who grew up speaking the Albanian dialect that the inhabitants of their Arbëresh town in the Italian province of Puglia have spoken for more than five centuries, the rapid decline of their mother tongue is a loss that is sorely felt. Musicians and cultural activists labor to negotiate new strategies for maintaining connections to their unique heritage and impart their traditions to young people who are raised speaking Italian in an increasingly interconnected world. As they perform, they are able to act out collective narratives of longing and belonging, history, nostalgia, and sense of place. Using the traditional song “Rine Rine” as a point of departure, this thesis examines how songs transmit linguistic and cultural markers of Arbëresh identity and serve to illuminate Chieuti’s position as a community poised in the moment of language shift. ii For my grandfather, Vincenzo Antonio Belpulso and for the children of Chieuti, at home and abroad, who carry on. -

ATINER's Conference Paper Series LNG2015-1524

ATINER CONFERENCE PAPER SERIES No: LNG2014-1176 Athens Institute for Education and Research ATINER ATINER's Conference Paper Series LNG2015-1524 Applying Current Methods in Documentary Linguistics in the Documentation of Endangered Languages: A Case Study on Fieldwork in Arvanitic Efrosini Kritikos Independent Researcher Harvard University USA 1 ATINER CONFERENCE PAPER SERIES No: LNG2015-1524 An Introduction to ATINER's Conference Paper Series ATINER started to publish this conference papers series in 2012. It includes only the papers submitted for publication after they were presented at one of the conferences organized by our Institute every year. This paper has been peer reviewed by at least two academic members of ATINER. Dr. Gregory T. Papanikos President Athens Institute for Education and Research This paper should be cited as follows: Kritikos, E. (2015). "Applying Current Methods in Documentary Linguistics in the Documentation of Endangered Languages: A Case Study on Fieldwork in Arvanitic", Athens: ATINER'S Conference Paper Series, No: LNG2015-1524. Athens Institute for Education and Research 8 Valaoritou Street, Kolonaki, 10671 Athens, Greece Tel: + 30 210 3634210 Fax: + 30 210 3634209 Email: [email protected] URL: www.atiner.gr URL Conference Papers Series: www.atiner.gr/papers.htm Printed in Athens, Greece by the Athens Institute for Education and Research. All rights reserved. Reproduction is allowed for non-commercial purposes if the source is fully acknowledged. ISSN: 2241-2891 19/07/2015 ATINER CONFERENCE PAPER SERIES No: LNG2015-1524 Applying Current Methods in Documentary Linguistics in the Documentation of Endangered Languages: A Case Study on Fieldwork in Arvanitic Efrosini Kritikos Independent Researcher Harvard University USA Abstract Arvanitic is a language of Greece also called Arberichte or Arvanitika. -

Historical Notes on Some Surnames and Patronymics Associated with the Clan Grant

Historical Notes on Some Surnames and Patronymics Associated with the Clan Grant Introduction In 1953, a little book entitled Scots Kith & Kin was first published in Scotland. The primary purpose of the book was to assign hundreds less well-known Scottish surnames and patronymics as ‘septs’ to the larger, more prominent highland clans and lowland families. Although the book has apparently been a commercial success for over half a century, it has probably disseminated more spurious information and hoodwinked more unsuspecting purchasers than any publication since Mao Tse Tung’s Little Red Book. One clue to the book’s lack of intellectual integrity is that no author, editor, or research authority is cited on the title page. Moreover, the 1989 revised edition states in a disclaimer that “…the publishers regret that they cannot enter into correspondence regarding personal family histories” – thereby washing their hands of having to defend, substantiate or otherwise explain what they have published. Anyone who has attended highland games or Scottish festivals in the United States has surely seen the impressive lists of so-called ‘sept’ names posted at the various clan tents. These names have also been imprinted on clan society brochures and newsletters, and more recently, posted on their websites. The purpose of the lists, of course, is to entice unsuspecting inquirers to join their clan society. These lists of ‘associated clan names’ have been compiled over the years, largely from the pages of Scots Kith & Kin and several other equally misleading compilations of more recent vintage. When I first joined the Clan Grant Society in 1977, I asked about the alleged ‘sept’ names and why they were assigned to our clan. -

Andrew Wear English Medical Writers and Their Interest in Classical Arabic Medicine in the Seventeenth Century

ANDREW WEAR ENGLISH MEDICAL WRITERS AND THEIR INTEREST IN CLASSICAL ARABIC MEDICINE IN THE SEVENTEENTH CENTURY In 1539 Sir Thomas Elyot wrote by way of introduction to his Caste I of Health: And afterward by mine own study, I read over in order the most part of the works of Hippocrates, Galen, Oribasius, Paulus Celius, Alexander Trallianus, Celsus, Plinius and one and the other, with Dioscorides. Nor did I omit to read the long Canons of Avicenna, the commentaries of Averroes the practises of Isaac, Haly Abbas, Rasis, Mesue, and also of the more part of them which were their aggregators and followers.1 Such enthusiasm for Arabic medicine was to be rare in England in the century that followed. The reasons for this are relatively easy to discern. In European terms Elyot already was becoming old-fashioned. The sixteenth century saw the near demise of Arabic medicine. The humanists, led by men such as Leoniceno, Manardi and Fuchs, rejected the Arabic and the medieval Latin writers. The retrieval of aprisca medicina based on Hippocrates and Galen necessitated the rejection, in principle at least, of all intermediary writers.The latter, it was thought, had not only clouded the pure fount of medicine with regard to content, but had also spoiled the language of medicine with barbarrous non-classical, neologisms. However, despite protestations of principle, knowledge of Arabic medi cine was quite widespread amongst European, and especially Italian, medical writers. Avicenna's Canon, for instance, with its useful paraphrase of Galenic doctrines remained in the medical curriculum until the eighteenth century. -

The Role and Importance of Translation for the Albanian Culture

The Role and Importance of Translation for the Albanian Culture La función y la importancia de la traducción para la cultura albanesa ARBEN SHALA Charles University, Faculty of Arts, nám. Jana Palacha 1/2, 116 38 Staré Město, Czechia. Dirección de correo electrónico: [email protected] ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0495-7884 Recibido: 17/10/2020. Aceptado: 15/9/2020. Cómo citar: Shala, Arben, «The Role and Importance of Translation for the Albanian Culture», Hermēneus. Revista de Traducción e Interpretación, 22 (2020): 383-413. DOI: https://doi.org/10.24197/her.22.2020.383-413 Abstract: This paper outlines the importance of translation activity for the Albanian culture beginning from the earliest period, as a driving force and forerunner of the Albanian National Awakening and identity, to the latest developments related to the quantity of translations, as well as their quality, peacebuilding in Kosovo and the use of translation for subversive propaganda. Translation, along with religion and masterpieces of world literature, brought different alphabetic scripts, many foreign words and, despite the adversarial approach by the Church and ruling authorities, contributed to the codification efforts, language purification and the coining of new words. Common expressions and folklore were collected and found their way into translated texts, now serving as grounds to call for retranslation. Keywords: Translation, national awareness, folklore, standardisation, tolerance. Resumen: Este artículo trata de describir la importancia de la actividad de traducción para la cultura albanesa desde el primer período, como fuerza impulsora y precursora del despertar nacional y la identidad albanesa, hasta los últimos desarrollos relacionados con la calidad y cantidad de la traducción, la construcción de la paz en Kosovo y el uso de la traducción como propaganda subversiva.