Leitrim Physical Geography Chapter Hegarty.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Changing Ireland

CHANGING IRELAND The Turn-around of the Turn-around in the Population of the Republic of Ireland. James A. Walsh Department of Geography, St. Patrick's College, Maynooth. The provisional results of the 1991 census of review of the components of change. This is followed population indicate a continuation of trends established by an examination of the spatial patterns of change in relation to fertility and migration in the early 1980s which result from their interaction and by a (Cawley, 1990) which have resulted in a halting of the consideration of the changes which have occurred in growth in population that commenced in the early the age composition of the population, examining how 1960s. It is estimated that the total population declined these adjustments have varied across the state. Since by approximately 17,200 (0.5%) since 1986 giving an the demographic outcome from the 1980s is different estimated total of 3,523,401 for 1991. In contrast to the in many respects from that of the 1970s, some of the 1970s, when there was widespread population growth, key areas of contrast will be noted throughout. the geographical pattern of change for the late 1980s is one of widespread decline, except in the immediate hinterlands of the largest cities. The provisional Components of Change estimates issued by the Central Statistics Office (CSO) in three publications are based on summaries returned The total change in the population over an inter- to the CSO by each of the 3,200 enumerators involved censal period is the outcome of the relationship between, in the carrying out of the census and, as such, are natural increase (births minus deaths) and net migration. -

Copyrighted Material

18_121726-bindex.qxp 4/17/09 2:59 PM Page 486 Index See also Accommodations and Restaurant indexes, below. GENERAL INDEX Ardnagashel Estate, 171 Bank of Ireland The Ards Peninsula, 420 Dublin, 48–49 Abbey (Dublin), 74 Arigna Mining Experience, Galway, 271 Abbeyfield Equestrian and 305–306 Bantry, 227–229 Outdoor Activity Centre Armagh City, 391–394 Bantry House and Garden, 229 (Kildare), 106 Armagh Observatory, 394 Barna Golf Club, 272 Accommodations. See also Armagh Planetarium, 394 Barracka Books & CAZ Worker’s Accommodations Index Armagh’s Public Library, 391 Co-op (Cork City), 209–210 saving money on, 472–476 Ar mBréacha-The House of Beach Bar (Aughris), 333 Achill Archaeological Field Storytelling (Wexford), Beaghmore Stone Circles, 446 School, 323 128–129 The Beara Peninsula, 230–231 Achill Island, 320, 321–323 The arts, 8–9 Beara Way, 230 Adare, 255–256 Ashdoonan Falls, 351 Beech Hedge Maze, 94 Adrigole Arts, 231 Ashford Castle (Cong), 312–313 Belfast, 359–395 Aer Lingus, 15 Ashford House, 97 accommodations, 362–368 Agadhoe, 185 A Store is Born (Dublin), 72 active pursuits, 384 Aillwee Cave, 248 Athlone, 293–299 brief description of, 4 Aircoach, 16 Athlone Castle, 296 gay and lesbian scene, 390 Airfield Trust (Dublin), 62 Athy, 102–104 getting around, 362 Air travel, 461–468 Athy Heritage Centre, 104 history of, 360–361 Albert Memorial Clock Tower Atlantic Coast Holiday Homes layout of, 361 (Belfast), 377 (Westport), 314 nightlife, 386–390 Allihies, 230 Aughnanure Castle (near the other side of, 381–384 All That Glitters (Thomastown), -

Appendices A-D.Pdf

Leitrim County Development Plan 2015 – 2021 Volume 2 : Appendices A-D LEITRIM COUNTY DEVELOPMENT PLAN 2015 - 2021 VOLUME I Volume 2: Appendices (A - D) LEITRIM COUNTY DEVELOPMENT PLAN 2015 - 2021 VOLUME I Volume 2 Appendices (A-D) APPENDIX A RECORD OF PROTECTED STRUCTURES .................................................................................................................. 1 APPENDIX B RECOMMENDED MINIMUM FLOOR AREAS AND STANDARDS ...................................................................................18 APPENDIX C COUNTY GEOLOGICAL SITES OF INTEREST ............................................................................................................20 APPENDIX D GUIDELINES ON FLOOD RISK AND DEVELOPMENT ................................................................................................ 23 LEITRIM COUNTY DEVELOPMENT PLAN 2015 - 2021 Appendices Appendix A Record of Protected Structures Table A List of Protected Structures Registration Registration Year of No. 2000 No. 2004 Adoption Area No. Townland Description Address 30902402 30924006 1991 3 1 Aghacashel Aghacashel House 30903501 30935002 1979 3 2 Annaduff Roman Catholic Church 30903202 30815012 1979 3 3 Annaduff Church of Ireland 30903306 1979 6 5 Aughavas Church of Ireland 30900505 1997 5 6 Ballaghameehan Roman Catholic Church 30903004 30930001 1979 6 7 Carrigallen Glebe House 30903011 30812010 1979 6 8 Carrigallen Roman Catholic Church 30903009 30812003 1979 6 9 Carrigallen Church of Ireland 30903208 30932001 1991 6 10 Clooncahir Lough Rynn -

Leitrim Council

Development Name Address Line 1 Address Line 2 County / City Council GIS X GIS Y Acorn Wood Drumshanbo Road Leitrim Village Leitrim Acres Cove Carrick Road (Drumhalwy TD) Drumshanbo Leitrim Aigean Croith Duncarbry Tullaghan Leitrim Allenbrook R208 Drumshanbo Leitrim 597522 810404 Bothar Tighernan Attirory Carrick-on- Shannon Leitrim Bramble Hill Grovehill Mohill Leitrim Carraig Ard Lisnagat Carrick-on- Shannon Leitrim 593955 800956 Carraig Breac Carrick Road (Moneynure TD) Drumshanbo Leitrim Canal View Leitrim Village Leitrim 595793 804983 Cluain Oir Leitrim TD Leitrim Village Leitrim Cnoc An Iuir Carrick Road (Moneynure TD) Drumshanbo Leitrim Cois Locha Calloughs Carrigallen Leitrim Cnoc Na Ri Mullaghnameely Fenagh Leitrim Corr A Bhile R280 Manorhamilton Road Killargue Leitrim 586279 831376 Corr Bui Ballinamore Road Aughnasheelin Leitrim Crannog Keshcarrigan TD Keshcarrigan Leitrim Cul Na Sraide Dromod Beg TD Dromod Leitrim Dun Carraig Ceibh Tullylannan TD Leitrim Village Leitrim Dun Na Bo Willowfield Road Ballinamore Leitrim Gleann Dara Tully Ballinamore Leitrim Glen Eoin N16 Enniskillen Road Manorhamilton Leitrim 589021 839300 Holland Drive Skreeny Manorhamilton Leitrim Lough Melvin Forest Park Kinlough TD Kinlough Leitrim Mac Oisin Place Dromod Beg TD Dromod Leitrim Mill View Park Mullyaster Newtowngore Leitrim Mountain View Drumshanbo Leitrim Oak Meadows Drumsna TD Drumsna Leitrim Oakfield Manor R280 Kinlough Leitrim 581272 855894 Plan Ref P00/631 Main Street Ballinamore Leitrim 612925 811602 Plan Ref P00/678 Derryhallagh TD Drumshanbo -

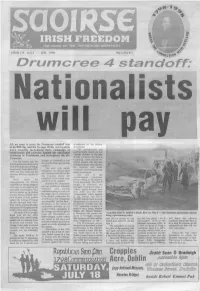

Drumcree 4 Standoff: Nationalists Will

UIMH 135 JULY — IUIL 1998 50p (USA $1) Drumcree 4 standoff: Nationalists will AS we went to press the Drumcree standoff was climbdown by the British in its fifth day and the Orange Order and loyalists government. were steadily increasing their campaign of The co-ordinated and intimidation and pressure against the nationalist synchronised attack on ten Catholic churches on the night residents in Portadown and throughout the Six of July 1-2 shows that there is Counties. a guiding hand behind the For the fourth year the brought to a standstill in four loyalist protests. Mo Mowlam British government looks set to days and the Major government is fooling nobody when she acts back down in the face of Orange caved in. the innocent and seeks threats as the Tories did in 1995, The ease with which "evidence" of any loyalist death 1996 and Tony Blair and Mo Orangemen are allowed travel squad involvement. Mowlam did (even quicker) in into Drurncree from all over the Six Counties shows the The role of the 1997. constitutional nationalist complicity of the British army Once again the parties sitting in Stormont is consequences of British and RUC in the standoff. worth examining. The SDLP capitulation to Orange thuggery Similarly the Orangemen sought to convince the will have to be paid by the can man roadblocks, intimidate Garvaghy residents to allow a nationalist communities. They motorists and prevent 'token' march through their will be beaten up by British nationalists going to work or to area. This was the 1995 Crown Forces outside their the shops without interference "compromise" which resulted own homes if they protest from British policemen for in Ian Paisley and David against the forcing of Orange several hours. -

Annals of the Kingdom of Ireland

COLONEL- MALCOLM- OF POLTALLOCH CAMPBELL COLLECTION Rioghachca emeaNN. ANNALS OF THE KINGDOM OF IEELAND, BY THE FOUR MASTERS, KKOM THE EARLIEST PERIOD TO THE YEAR 1616. EDITED FROM MSS. IN THE LIBRARY OF THE ROYAL IRISH ACADEMY AND OF TRINITY COLLEGE, DUBLIN, WITH A TRANSLATION, AND COPIOUS NOTES, BY JOHN O'DONOYAN, LLD., M.R.I.A., BARRISTER AT LAW. " Olim Regibus parebaut, nuuc per Principes faction! bus et studiis trahuntur: nee aliud ad versus validiasiuias gentes pro uobis utilius, qnam quod in commune non consulunt. Rarus duabus tribusve civitatibus ad propulsandum eommuu periculom conventus : ita dum singnli pugnant umVersi vincuntur." TACITUS, AQBICOLA, c. 12. SECOND EDITION. VOL. VII. DUBLIN: HODGES, SMITH, AND CO., GRAFTON-STREET, BOOKSELLERS TO THE UNIVERSITY. 1856. DUBLIN : i3tintcc at tije ffinibcrsitn )J\tss, BY M. H. GILL. INDEX LOCORUM. of the is the letters A. M. are no letter is the of Christ N. B. When the year World intended, prefixed ; when prefixed, year in is the Irish form the in is the or is intended. The first name, Roman letters, original ; second, Italics, English, anglicised form. ABHA, 1150. Achadh-bo, burned, 1069, 1116. Abhaill-Chethearnaigh, 1133. plundered, 913. Abhainn-da-loilgheach, 1598. successors of Cainneach of, 969, 1003, Abhainn-Innsi-na-subh, 1158. 1007, 1008, 1011, 1012, 1038, 1050, 1066, Abhainn-na-hEoghanacha, 1502. 1108, 1154. Abhainn-mhor, Owenmore, river in the county Achadh-Chonaire, Aclionry, 1328, 1398, 1409, of Sligo, 1597. 1434. Abhainn-mhor, The Blackwater, river in Mun- Achadh-Cille-moire,.4^az7wre, in East Brefny, ster, 1578, 1595. 1429. Abhainn-mhor, river in Ulster, 1483, 1505, Achadh-cinn, abbot of, 554. -

Dromahair ~ Killargue ~ Newtownmanor

Parish Website: www.drumlease-killargue.com Fr. John Me Tiernan ~ 071- 9164143/Fr. John Sexton ~ 071 - 9164131. Dromahair ~ Killargue ~ Newtownmanor Sunday 7th February 2010 ~ The Fifth Sunday in Ordinary Time. Sunday Next is Valentine's Dav. There will be a blessing for all couples at Masses next weekend. £A] A Date for Your Diary: Ash Wednesdays on the 17th February this year. Details concerning blessing & distribution of ashes and Mass times will be given next week. [B] St. Michael's family Life Centre, Church Hill, Sligo: Telephone 071 - 9170329. A Parenting Course dealing with children of all ages begins this Tuesday 9th February at 10.00am. If you have suffered loss or bereavement, you may be interested in Journey through Grief, a course that aims to help you cope in times of loneliness and pain. Excellent morning and night programmes also. Web- site: [email protected] [C] Alcoholic Anonymous ~ Open Public Meeting: Bee Park Centre (Conference Room 1) Manorhamilton, Co. Leitrim on Wednesday 10th February at 8.00pm. All invited to attend this information evening on Alcoholics Anonymous and AI-Anon. Refreshments served. [D] First Friday Visitation ~ Killarouearea: Monday 8th, Tuesday 9th & Wednesday 10th February. AH concerned will be contacted to arrange a suitable time. [E] We remember Margaret (Margie) Mather (sister of PJ.Devaney, Corrigeencor & Eileen Coen, Sligo) whose funeral took place in Newcastle, England on Tuesday 26th January. May she rest in peace. ST. PATRICK'S CHURCH, DROMAHAIR. 1. Mass: Monday9.30am; Tuesday93Qam] Wednesday9.30am; Friday8.00pm-, Sunday 11.15am. 2. Prav for:- Harold Atkins, Lavally, Ballintogher & deceased family, Mass Sunday 7th February at 11.15am. -

Dromahair ~ Killargue ~ Newtownmanor

Parish Website: www.drumlease-killargue.com Fr. Anthony Fagan P.P. 071- 9164143 Dromahair – Killargue - Newtownmanor Sunday 11th November 2018 – 32nd Sunday in Ordinary Time World Meeting Families – 2018 The 5th National Collection in support of the World Meeting of Families held last August, will be taken up after Holy Communion in all three churches this weekend – 10th & 11th November. Thank you for your continuing generosity. Change of Mass Time – Killargue: With effect from this Saturday - 10th November 2018, the Saturday Evening Vigil Mass in Killargue has reverted to the earlier time of 7.00pm, for the winter months. Why not as a family, remember your deceased loved ones in November There will be an opportunity to do so at Special Masses in the parish, as follows: Killargue Church on Wednesday 28th November at 7.00pm; Dromahair Church on Friday 30th November at 8.00pm. Families will have an opportunity to place a remembrance candle before the Altar during Mass. Church Notices: [A] Altar Servers for Dromahair in November 2018 – Group 1. Parents please note, if your child is unable to serve at Mass on any of the assigned dates, please arrange a replacement. [B] World Mission Sunday: If you would like to contribute to the Mission Sunday collection or have forgotten, you will find the pink Mission Sunday Collection Envelope between the October and November envelopes in your Dues pack, or just use an ordinary envelope. Don’t forget to include your name and address. Thanks for your continuing generosity. [C] November is the month when we remember our Departed Loved Ones and all the Holy Souls. -

Leitrim County Council Noise Action Plan 2018-2023

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Noise Action Plan 2018-2023 has been prepared by Leitrim Local Authority to address environmental noise from major roads with more than three million vehicles per annum. The action planning area covers the N4 (Dublin-Sligo) and N15 (Sligo-Letterkenny). This is the second Noise Action Plan for Co. Leitrim; the first Action Plan was for the period 2013 - 2018. The plan has been prepared in accordance with the requirements of EU Directive 2002/49/EC (known as the Environmental Noise Directive, or “END”), which was transposed into Irish Law by the Environmental Noise Regulations 2006, SI No. 140 of 2006. The aim of the Directive and the Regulations is to provide for the implementation of an EC common approach to avoid, prevent or reduce on a prioritized basis the harmful effects, including annoyance, due to exposure to environmental noise. Environmental noise is unwanted or harmful outdoor sound created by human activities, including noise emitted by means of transport, road traffic, rail traffic, air traffic and noise in agglomerations over a specified size. Types of noise not included in the Regulations are noise that is caused by the exposed person, noise from domestic activities, noise created by neighbours, noise at workplaces or noise inside means of transport or due to military activities in military areas. Noise Mapping Bodies and Action Planning Authorities were assigned responsibility under the regulations to draw up strategic noise maps for the third round in 2017 and prepare action plans for noise from the following noise sources: sections of rail route above a flow threshold of 30,000 train passages per year (Not applicable to Co. -

Wrap U P in Culture

WHAT ARE YOU LEITRIM N I DOING ON 2019 CULTURE NIGHT? Manorhamilton P Glenfarne Dromahair U On the evening of Friday September 20th, Leitrim comes alive with events across the county. So start planning your evening now – and remember, everything is free! For nationwide events see: www. culturenight.ie CULTURE WRAP Ballinamore Carrigallen Carrick on Shannon Mohill Drumsna Leitrim County Council Arts Office Carrick on Shannon Co. Leitrim 071 96 21694 [email protected] www.leitrimarts.ie Culture Night is brought to you by the Department of Culture, Heritage & the Gaeltacht and the Creative Ireland Programme in partnership with Leitrim County Council. An Roinn Ealaíon, Oidhreachta agus Gaeltachta a dhéanann comhordú ar an FRI Oíche Chultúir, i gcomhpháirt le Comhairle Contae Liatroma. 20 SEP CULTURENIGHT.IE WWW. LEITRIMARTS.IE LEITRIM 2019 BALLINAMORE MUSICAL PERFORMANCE LEITRIM DESIGN HOUSE THE OLIVE TREE CAFÉ CARRIGALLEN DROMAHAIR MANORHAMILTON LSC GALLERY: TRACES - MAPPING With Rhona Trench (Silver flute), Carole Coleman MEMORY & PLACE IN MANORHAMILTON (Irish flute), Edel Rowley (Silver Flute), Alla Crosbie, 6.30PM – 7.15PM SOLAS GALLERY (Piano/singer) Enda Stenson (Bodhrán). HOMEMADE PAINT WORKSHOP AN EVENING OF LIVE MUSIC & SONG CORN MILL THEATRE ‘I will arise and go now and go to IONAD NA nGLEANNTA / FOR ALL AGES! 4PM-5.30PM 7PM – 8.30PM Inisfree…’ Artist Sandra Corrigan-Breathnach performance DEPARTING FROM PARKE’S CASTLE 7.30PM THE GLENS CENTRE CULTURE NIGHT@ SOLAS GALLERY CREATIVE EYE PHONE WORKSHOP THIS IS YOUR THEATRE: CELEBRATING & exhibition in collaboration with The Womens WITH ANNA LEASK Kate Murtagh Sheridan will encourage participants Curated by alt folk duo ‘The Shrine of St Lachtain’s Centre; The Kilgar Group; the 24/7 Carers Group; 7.30PM – 10PM to be creative by teaching them to make and use Arm’ with special guest Colin Beggan. -

GROUP / ORGANISATION Name of TOWN/VILLAGE AREA AMOUNT

GROUP / ORGANISATION AMOUNT AWARDED by LCDC Name of TOWN/VILLAGE AREA Annaduff ICA Annaduff €728 Aughameeney Residents Association Carrick on Shannon €728 Bornacoola Game & Conservation Club Bornacoola €728 Breffni Family Resource Centre Carrick on Shannon €728 Carrick-on Shannon & District Historical Society Carrick on Shannon €646 Castlefore Development Keshcarrigan €728 Eslin Community Association Eslin €729 Gorvagh Community Centre Gorvagh €729 Gurteen Residents Association Gurteen €100 Kiltubrid Church of Ireland Restoration Kiltubrid €729 Kiltubbrid GAA Kiltubrid €729 Knocklongford Residents Association Mohill €729 Leitrim Cycle Club Leitrim Village €729 Leitrim Gaels Community Field LGFA Leitrim Village €729 Leitrim Village Active Age Leitrim Village €729 Leitrim Village Development Leitrim Village €729 Leitrim Village ICA Leitrim Village €729 Mohill GAA Mohill €729 Mohill Youth Café Mohill €729 O Carolan Court Mohill €728 Rosebank Mens Group Carrick on Shannon €410 Saint Mary’s Close Residence Association Carrick on Shannon €728 Caisleain Hamilton Manorhamilton €1,000 Dromahair Arts & Recreation Centre Dromahair €946 Killargue Community Development Association Killargue €423 Kinlough Community Garden Kinlough €1,000 Manorhamilton ICA Manorhamilton €989 Manorhamilton Rangers Manorhamilton €100 North Leitrim Womens Centre Manorhamilton €757 Sextons House Manorhamilton €1,000 Tullaghan Development Association Tullaghan €1,000 Aughavas GAA Club Aughavas €750 Aughavas Men’s Shed Aughavas €769 Aughavas Parish Improvements Scheme Aughavas -

Minutes of Meeting of Carrick on Shannon Municipal District Held in Council Chamber, Aras an Chontae, Carrick on Shannon, Co. Le

Minutes of Meeting of Carrick on Shannon Municipal District Held in Council Chamber, Aras an Chontae, Carrick on Shannon, Co. Leitrim On Tuesday 10th January 2017 at 3.35 pm Members Present: Councillor Finola Armstrong McGuire Councillor Des Guckian Councillor Sinead Guckian Councillor Enda Stenson Councillor Séadhna Logan Councillor Sean McGowan Officials Present: Johanna Daly, Meetings Administrator Joseph Gilhooly, Director of Services, Economic Development, Planning, Environment & Transportation Darragh O’Boyle, District Engineer South Leitrim Shay O’Connor, Senior Engineer, Roads Bernard Greene, Senior Planner Pamela Moran, Economic Development, Planning, Environment & Transportation CMD 17/01 Minutes of the Meeting of Carrick on Shannon Municipal District 10/01/17 held on Monday 5th December 2016 Proposed by Councillor Des Guckian, Seconded by Councillor Sinead Guckian AND UNANIMOUSLY RESOLVED; “That the Minutes of Carrick on Shannon Municipal meeting held in Aras an Chontae, Carrick on Shannon, Co. Leitrim on Monday 5th December 2016 be adopted.” Matters arising from Minutes Item CMD16/157 – omission of the word “not” – correct sentence should read “These notices have not been complied with and the matter has since been referred to the Council’s Legal Representative for relevant action through the Courts.” CMD17/02 Correspondence 10/01/17 Johanna Daly, Meetings Administrator informed the members that she had received two separate items of correspondence in advance of today’s meeting. A copy of these items was circulated to the members. Item No. 1 Copy of “Draft Appointed Stand (Taxis) Bye-laws 2017 – Carrick on Shannon Train Station” issued by Roscommon County Council (this appears as Appendix 1 to these Minutes).