Downloading Material Is Agreeing to Abide by the Terms of the Repository Licence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Call for Sites 2021 Justification Statement V3

Planning Justification Statement Representation to Hertsmere Local Plan Process Commercial Redevelopment Land and Buildings at the Mercure Hotel Watford, A41 Bypass WD25 8JH March 2021 Contents 1. Introduction 2 2. The Site 4 3. The Proposal 7 4. Exceptional Circumstances 12 5. Economic Need 16 6. Green Belt and Landscape 25 7. Transport and Accessibility 31 8. Flood Risk 34 9. Ecology and Trees 37 10. Heritage 40 11. Other Technical Matters 41 12. Case of Exceptional Circumstances 43 13. Conclusion 51 Appendix A: Site Planning History 1 1. Introduction This Planning Justification Statement is submitted by Warner Planning on behalf of Regen Properties LLP. This submission is made to the Hertsmere Borough Council 'Employment Land Call for Sites' 2021. We promote land and buildings at the Mercure Hotel Watford, A41 Bypass WD25 8JH for allocation for B8 with ancillary B1 commercial development. The hotel has been struggling for several years, which has been further compounded by the Covid-19 Pandemic, and the hotel is due to close in late 2021/early 2022. This statement, therefore, provides representations in respect of the whole site, including the hotel buildings and the land to the south-east of the building, which is part of the same plot. Through this statement, we will demonstrate that this is a credible and deliverable opportunity with no technical issues. This submission is supported by a wealth of technical reports, including: • Masterplans – UMC • Economic Benefits Assessment - Lichfields • Landscape Visual Overview – CSA Environmental • Ecology Overview- CSA Environmental • Aboricultural Assessment – DCCLA • Flood Risk and Drainage Apprisal – EAS • Transport Review – EAS • Desk Based Phase 1 Environmental Site Assessment – TRC • This Statement – Warner Planning • Market Report – Knight Frank • Employment Call for Sites Submission Form There are limited alternatives to this proposal. -

A Guide to Local and Welsh Newspapers and Microfilm in Swansea Central Library

A guide to Local and Welsh Newspapers and Microfilm in Swansea Central Library Current Local Newspapers These are located on the first floor of the Central Library. Please ask at the desk for the location. South Wales Evening Post (Daily) (Earlier issues are available in various formats. Please see below for details.) Online Newspaper Databases Swansea Library card holders can access various newspaper databases via our Online Resources webpage. The British Newspaper Archive provides searchable access to 600 digitised regional and national newspaper titles, dating from 1710-1959, taken from the collections of the British Library. It includes the South Wales Daily Post from 1893-1899 and other Welsh titles. You can only access this site from inside a Swansea library. You will also need to register on the site and provide an email address to view images. Our contemporary newspaper database, NewsBank, provides searchable versions of various current British national newspapers and the following Welsh newspapers. The description in brackets shows the areas they cover if unclear. This database does not include a newspaper’s photographs. Period Covered Carmarthen Journal 2007 – Current Daily Post [North Wales] 2009 – Current Glamorgan Gazette [Mid Glamorgan/Bridgend] 2005 – Current Llanelli Star 2007 – Current Merthyr Express 2005 – Current Neath Guardian 2005 – 2009 Port Talbot Guardian 2005 – 2009 South Wales Argus [Newport/Gwent] 2007 – Current South Wales Echo [Cardiff/South Glamorgan] 2001 – Current South Wales Evening Post [Swansea/West -

The Warrior £2.00 the Newsletter from the LMS-PATRIOT PROJECT Issue 19 • September 2013 Patriot Front End Revealed for the First Time Since 1963

The Warrior £2.00 The Newsletter FROM THE LMS-PATRIOT PROJECT Issue 19 • September 2013 Patriot Front End revealed for the first time since 1963 The front of a Patriot was seen for the first time since 1963 when 45551 ‘The Unknown Warrior’ was photographed for a fundraising photoshoot at the Llangollen Railway Works at the end of July. As you will have no doubt seen, this iconic shot adorned the front cover of Steam Railway magazine (Issue 418, published on 16th August) and came about as part of a general appeal to raise £150,000 to complete the bottom end. A new fundraising leaflet was also inserted in every copy of Steam Railway magazine. The smoke box had been finished at LNWR Heritage at Crewe on 29th May and transported to the Llangollen Railway in time for Members’ Day on 15th June (see separate report). The painting was undertaken by Patriot Project and Llangollen Railway Members including Godfrey Hall and John Sandiford. The paint generously sponsored and supplied by Photo by Keith Langston Bromborough Paints. The paint for ‘The Unknown Warrior’ has been kindly supplied by bromboroughpaints.co.uk The Newsletter FROM THE LMS-PATRIOT PROJECT Engineering Update • The driving wheelsets are have been completed by South Devon Railway Engineering and were delivered to Tyseley Loco Works on the 3rd July – the same day that a well-known blue LNER A4 Pacific was making all the headlines! The driving wheelsets are at Tyseley for tyre turning, wheel balancing and axleboxes will be fitted prior to transporting to Llangollen for fitting to the frames (see photo top right). -

Combining Scheduled Commuter Services with Private Hire, Sightseeing and Tour Work: the London Experience by Derek Kenneth Robbins and Peter Royden White*

CEE INGS Twenty-sixth Annual Meeting Theme: "Markets and Management in an Era of Deregulation" November 13-15, 1985 Amelia Island Plantation Jacksonville, Florida Volume XXVI Number 1 1985 TRANSPORTATION RESEARCH FORUM In conjunction with CANADIAN TRANSPORTATION 4 RESEARCH FORM 273 Combining Scheduled Commuter Services with Private Hire, Sightseeing and Tour Work: The London Experience By Derek Kenneth Robbins and Peter Royden White* ABSTRACT dent operators ran only 8% of stage carriage mileage but operated 91% of private hire and contract The Transport Act 1980 completely removed mileage and 86% of all excursions and tours quantity control for scheduled express services mileage.' The 1980 Transport Act removed the which carry passengers more than 30 miles meas- quantity controls for two of the types of operation, ured in a straight line. It also made road service namely scheduled express services and most excur- licenses easier to obtain for operators wishing to run sions and tours. However the quality controls were services over shorter distances by limiting the scope retained, in the case of vehicle maintenance and for objections. As a result of these legislative inspections being strengthened. The Act redefined changes a new type of service has emerged over the "scheduled express" services. Since 1930 they had last four years carrying long-distance commuters to been defined by the minimum fare charged and and from work in London. Vehicles used on such because of inflation many short distance services services would only be utilised for short periods came to be defined as "Express", despite raising the every weekday unless other work were also found minimum fare yardstick in both 1971 and 1976. -

160 Great Britain for Updates, Visit Wigan 27 28

160 Great Britain For Updates, visit www.routex.com Wigan 27 28 Birkenhead Liverpool M62 36 Manchester Stockport M56 Mold Chester 35 Congleton Wrexham 59 M6 Shrewsbury 64 65 07 Wolverhampton Walsall West Bromwich Llandrindod Birmingham Wells Solihull M6 03 Coventry Warwick02 Carmarthen Hereford 01 51 60 Neath M5 Swansea 06 Pontypridd Bridgend Caerphilly Newport Cardiff M4 13 Barry Swindon M5 Bristol 61 14 Weston-super-Mare Kingswood 31 Bath 32 M4 05 Trowbridge 62 Newbury Taunton M5 20 Yeovil Winchester Exeter Southampton 55 Exmouth M27 Poole Lymington Bournemouth Plymouth Torbay Newport GB_Landkarte.indd 160 05.11.12 12:44 Great Britain 161 Wakefield 16 Huddersfield Hull Barnsley Doncaster Scunthorpe Grimsby Rotherham Sheffield M1 Louth 47M1 Heanor Derby Nottingham 48 24 Grantham 15 Loughborough 42 King's Leicester Lynn 39 40 Aylsham Peterborough Coventry Norwich GB 46 01 Warwick Huntingdon Thetford Lowestoft 45 M1 Northampton 02 43 44 Cambridge Milton Bedford Keynes Biggleswade Sawston 18 M40 19 Ipswich Luton Aylesbury Oxford Felixstowe Hertford 21 50 M25 M11 Chelmsford 61 30 53 52 Slough London Bracknell Southend-on-Sea Newbury Grays 54 Wokingham 29 Rochester Basingstoke 22 M3 Guildford M2 M25 Maidstone Winchester 23 M20 17 M27 Portsmouth Chichester Brighton La Manche Calais Newport A16 A26 Boulogne-sur-Mer GB_Landkarte.indd 161 05.11.12 12:44 162 Great Britain Forfar Perth Dundee 58 Stirling Alloa 34 Greenock M90 Dumbarton Kirkintilloch Dunfermline 57 Falkirk Glasgow Paisley Livingston Edinburgh Newton M8 Haddington Mearns 04 56 Dalkeith 26 Irvine Kilmarnock Ayr Hawick A74(M) 41 Dumfries 25 Morpeth Newcastle Carlisle Upon Whitley Bay 12Tyne 08 South Shields Gateshead 09 11 Durham 49 Redcar 33 Stockton-on-Tees M6 Middlesbrough 10 38 M6 A1(M) 37 Harrogate York 63 M65 Bradford Leeds Beverley M6 28 M62 Wakefield Wigan 16 27 Huddersfield Birkenhead Liverpool Manchester Barnsley M62 Scunthorpe 35 36Stockport Doncaster Rotherham Sheffield GB_Landkarte.indd 162 05.11.12 12:44 Great Britain 163 GPS Nr. -

Week Ending 14Th July 2021

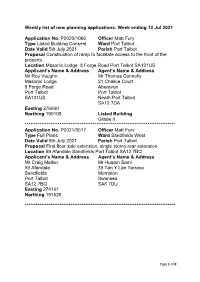

Weekly list of new planning applications. Week ending 12 Jul 2021 Application No. P2020/1066 Officer Matt Fury Type Listed Building Consent Ward Port Talbot Date Valid 5th July 2021 Parish Port Talbot Proposal Construction of ramp to facilitate access to the front of the property. Location Masonic Lodge 8 Forge Road Port Talbot SA131US Applicant’s Name & Address Agent’s Name & Address Mr Roy Vaughn Mr Thomas Connolly Masonic Lodge 21 Chalice Court 8 Forge Road Aberavon Port Talbot Port Talbot SA131US Neath Port Talbot SA12 7DA Easting 276660 Northing 190108 Listed Building Grade II ********************************************************************************** Application No. P2021/0517 Officer Matt Fury Type Full Plans Ward Sandfields West Date Valid 9th July 2021 Parish Port Talbot Proposal First floor side extension, single storey rear extension Location 59 Afandale Sandfields Port Talbot SA12 7BQ Applicant’s Name & Address Agent’s Name & Address Mr Craig Mallon Mr Husam Sami 59 Afandale 39 Tan Y Lan Terrace Sandfields Morriston Port Talbot Swansea SA12 7BQ SA6 7DU Easting 274161 Northing 191528 ********************************************************************************** Page 1 of 8 Application No. P2021/0632 Officer Daisy Tomkins Type Full Plans Ward Coedffranc Central Date Valid 6th July 2021 Parish Coedffranc Town Council Proposal First floor rear extension, balcony and screening. Location 66 New Road Skewen Neath SA10 6HA Applicant’s Name & Address Agent’s Name & Address Mr and Mrs Yip Mr Antony Walker 66 New Road AgW Architecture -

Revised Service 202 (Neath- Port Talbot)

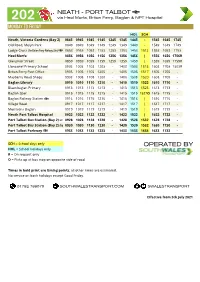

202 NEATH - PORT TALBOT via Heol Morfa, Briton Ferry, Baglan & NPT Hospital MONDAY TO FRIDAY HOL SCH Neath, Victoria Gardens (Bay 2) 0845 0945 1045 1145 1245 1345 1445 - 1545 1645 1745 Old Road, Melyn Park 0849 0949 1049 1149 1249 1349 1449 - 1549 1649 1749 Lodge Cross (for Briton Ferry Railway Stn) 0853 0953 1053 1153 1253 1353 1453 1512 1553 1653 1753 Heol Morfa 0856 0956 1056 1156 1256 1356 1456 | 1556 1656 1756R Glanymor Street 0859 0959 1059 1159 1259 1359 1459 | 1559 1659 1759R Llansawel Primary School 0903 1003 1103 1203 - 1403 1503 1515 1603 1703 1803R Briton Ferry Post Office 0905 1005 1105 1205 - 1405 1505 1517 1605 1705 - Mayberry Road Shops 0908 1008 1108 1208 - 1408 1508 1520 1608 1708 - Baglan Library 0910 1010 1110 1210 - 1410 1510 1522 1610 1710 - Blaenbaglan Primary 0913 1013 1113 1213 - 1413 1513 1525 1613 1713 - Baglan Spar 0915 1015 1115 1215 - 1415 1515 1527O 1615 1715 - Baglan Railway Station 0916 1016 1116 1216 - 1416 1516 | 1616 1716 - Village Road 0917 1017 1117 1217 - 1417 1517 | 1617 1717 - Morrisons Baglan 0919 1019 1119 1219 - 1419 1519 | 1619 1719 - Neath Port Talbot Hospital 0922 1022 1122 1222 - 1422 1522 | 1622 1722 - Port Talbot Bus Station (Bay 2) arr 0928 1028 1128 1228 - 1428 1528 1532 1628 1728 - Port Talbot Bus Station (Bay 2) dep 0930 1030 1130 1230 - 1430 1530 1532 1630 1730 - Port Talbot Parkway 0933 1033 1133 1233 - 1433 1533 1535 1633 1733 - SCH = School days only OPERATED BY HOL = School holidays only R = On request only O = Picks up at bus stop on opposite side of road Times in bold print are timing points; all other times are estimated. -

The M1 Motorway (Junctions 5 – 6A

THE M1 MOTORWAY(JUNCTIONS 5–6A) TEMPORARYOVERNIGHT CLOSURES Notice is hereby given that Highways England Company Limited(a) intends to make an Order on the M1 Motorway,inthe County of Hertfordshire, under Section 14(1)(a) of the Road Traffic Regulation Act 1984 because works areproposed to be executed on the road. The effect of the Order would be to authorise the overnight closureofthe following – (a) the slip roads leading to and from both carriageways of the M1 at Junction 5(A41, A4008); (b) the slip roads leading to and from both carriageways of the M1 at Junction 6(A405); and (c) the link road leading from the southbound carriageway of the M1 at Junction 6A to both carriageways of the M25 at Junction 21. These measures would be in the interest of road safety to enable contractors to undertake cyclical maintenance work. It is expected that the work would take place for approximately 1-2nights for each closureat(a) –(c) above every two months at the following times: Monday-Thursday nights 22:00 –05:30 Friday nights 23:00 –06:00 Saturday nights 22:00 –06:00 Sunday nights 22:30 –05:30 The Order would come into force on 1August2017 and have amaximum duration of twelve months. During the closures outlined above, traffic affected would be diverted using other junctions of the M1, the A41, the A405 and the A410. The slip road closures, link road closureand diversion routes would be clearly indicated by traffic signs throughout the works periods. MTaylor, an official of Highways England Company Limited Ref: HA/M1/35/3/1894 (a)Registered in England and Wales under company no. -

An Auction of London Bus, Tram, Trolleybus & Underground

£5 when sold in paper format Available free by email upon application to: [email protected] An auction of London Bus, Tram, Trolleybus & Underground Collectables Enamel signs & plates, maps, posters, badges, destination blinds, timetables, tickets & other relics th Saturday 29 October 2016 at 11.00 am (viewing from 9am) to be held at THE CROYDON PARK HOTEL (Windsor Suite) 7 Altyre Road, Croydon CR9 5AA (close to East Croydon rail and tram station) Live bidding online at www.the-saleroom.com (additional fee applies) TERMS AND CONDITIONS OF SALE Transport Auctions of London Ltd is hereinafter referred to as the Auctioneer and includes any person acting upon the Auctioneer's authority. 1. General Conditions of Sale a. All persons on the premises of, or at a venue hired or borrowed by, the Auctioneer are there at their own risk. b. Such persons shall have no claim against the Auctioneer in respect of any accident, injury or damage howsoever caused nor in respect of cancellation or postponement of the sale. c. The Auctioneer reserves the right of admission which will be by registration at the front desk. d. For security reasons, bags are not allowed in the viewing area and must be left at the front desk or cloakroom. e. Persons handling lots do so at their own risk and shall make good all loss or damage howsoever sustained, such estimate of cost to be assessed by the Auctioneer whose decision shall be final. 2. Catalogue a. The Auctioneer acts as agent only and shall not be responsible for any default on the part of a vendor or buyer. -

BD22 Neath Port Talbot Unitary Development Plan

G White, Head of Planning, The Quays, Brunel Way, Baglan Energy Park, Neath, SA11 2GG. Foreword The Unitary Development Plan has been adopted following a lengthy and com- plex preparation. Its primary aims are delivering Sustainable Development and a better quality of life. Through its strategy and policies it will guide planning decisions across the County Borough area. Councillor David Lewis Cabinet Member with responsibility for the Unitary Development Plan. CONTENTS Page 1 PART 1 INTRODUCTION Introduction 1 Supporting Information 2 Supplementary Planning Guidance 2 Format of the Plan 3 The Community Plan and related Plans and Strategies 3 Description of the County Borough Area 5 Sustainability 6 The Regional and National Planning Context 8 2 THE VISION The Vision for Neath Port Talbot 11 The Vision for Individual Localities and Communities within 12 Neath Port Talbot Cwmgors 12 Ystalyfera 13 Pontardawe 13 Dulais Valley 14 Neath Valley 14 Neath 15 Upper Afan Valley 15 Lower Afan Valley 16 Port Talbot 16 3 THE STRATEGY Introduction 18 Settlement Strategy 18 Transport Strategy 19 Coastal Strategy 21 Rural Development Strategy 21 Welsh Language Strategy 21 Environment Strategy 21 4 OBJECTIVES The Objectives in terms of the individual Topic Chapters 23 Environment 23 Housing 24 Employment 25 Community and Social Impacts 26 Town Centres, Retail and Leisure 27 Transport 28 Recreation and Open Space 29 Infrastructure and Energy 29 Minerals 30 Waste 30 Resources 31 5 PART 1 POLICIES NUMBERS 1-29 32 6 SUSTAINABILITY APPRAISAL Sustainability -

Access Wales & U.K. Newspapers

Access Wales & U.K. Newspapers Easy access to local, regional and national news Quick Facts Features more than 25 newspapers from across Wales Includes the major dailies and community newspapers Interface in English or Welsh Overview Designed specifically for libraries in Wales, Access Wales & U.K. Newspapers features popular news sources from within Wales, providing in-depth coverage of local and regional issues and events. Well-known sources from England, Scotland, Northern Ireland are also included, further expanding the scope of this robust research tool. Welsh News This collection of more than 25 Welsh newspapers offers users daily and weekly news sources of interest, including the North Wales edition of the Daily Post, the Western Mail and the South Wales Evening Post. News articles provide detailed coverage of businesses, government, sports, politics, the arts, culture, finance, health, science, education and more – from large and small cities alike. Daily updates keep users informed of the latest developments from the assembly government, farming news, rugby and cricket events, and much more. Retrospective articles - ideal for comparing today’s issues and events with past news - are included, as well. U.K. News This optional collection of more than 500 news sources provides in-depth coverage of issues and events within the U.K. and Ireland. Major national broadsides and tabloids are complemented by a list of popular daily, weekly and online news sources, including The Times (1985 forward), Financial Times, The Guardian, and The Scotsman. This robust collection keeps readers and researchers abreast of local and national news, as well as developments in nearby countries that impact life in Wales. -

Monmouthshire Health Walk - Black Rock Walk

Monmouthshire Health Walk - Black Rock Walk THE ROUTE 1 Turn right out of the car park entrance. Go through gate and right to follow the Wales Coastal Path to Sudbrook DISTANCE 3 miles / 5 kilometres 2 Just past the pumping station in Sudbrook, turn left across the old railway line, then turn left again on Camp Road 3 There are seats, by the Chapel ruins, a handy resting place with a view TIME 1 hour 30 mins 4 Follow the Wales Coastal Path round the camp rampart. Shortly afterwards, leave the coast path and turn right across a foot- ball field to a gap in the rampart GRADE 5 Pass through the rampart, pass a play area to your left and follow the track back to the main road Easy, no stiles, one foot- 6 Turn left on Sudbrook Road and follow it until you come to some traffic lights. Turn right through a gate, cross the field bridge with steps 7 Pass an electricity pylon on your left and go through a gate into the next field. Head towards the next pylon 8 Go through a gate on your left onto a track and follow this, parallel to the railway line to a footbridge STARTING POINT Black Rock Picnic Site Car 9 Cross the footbridge over the railway Park 10 Turn left on Station Road, then right on Hill Barn View and, after 10m, right again onto Sunny Croft 11 At the T-junction, turn right on Black Rock Road and follow this back to the car park POINTS OF INTEREST A Sudbrook Camp is a late iron age cliff top camp or fort, one of several along the South Wales coast.