The Nuremberg Principles: a Defense for Political Protesters, 40 Hastings L.J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Defending the Emergence of the Superior Orders Defense in the Contemporary Context

Goettingen Journal of International Law 2 (2010) 3, 871-892 Defending the Emergence of the Superior Orders Defense in the Contemporary Context Jessica Liang Table of Contents Abstract ............................................................................................................ 872 A. Introduction .......................................................................................... 872 B. Superior Orders and the Soldier‘s Dilemma ........................................ 872 C. A Brief History of the Superior Orders Defense under International Law ............................................................................................. 874 D. Alternative Degrees of Attributing Criminal Responsibility: Finding the Right Solution to the Soldier‘s Dilemma ..................................... 878 I. Absolute Defense ................................................................................. 878 II. Absolute Liability................................................................................. 880 III.Conditional Liability ............................................................................ 881 1. Manifest Illegality ..................................................................... 881 2. A Reasonableness Standard ...................................................... 885 E. Frontiers of the Defense: Obedience to Civilian Orders? .................... 889 I. Operation under the Rome Statute ....................................................... 889 II. How far should the Defense of Superior Orders -

Nuremberg Academy Annual Report 2018

Annual Report International Nuremberg Principles Academy 1 Imprint The Annual Report 2018 has been Executive Board: published by the International Klaus Rackwitz (Director), Nuremberg Principles Academy. Dr. Viviane Dittrich (Deputy Director) It is available in English, German Edited by: and French and can be ordered Evelyn Müller at [email protected] Layout: or be downloaded on the website Martin Küchle Kommunikationsdesign www.nurembergacademy.org. Photos: Egidienplatz 23 International Nuremberg Principles Academy 90403 Nuremberg, Germany p. 9 Strathmore University, p. 20 Wayamo T + 49 (0) 911.231.10379 Foundation F + 49 (0) 911.231.14020 Printed by: [email protected] Druckwerk oHG Table of Contents 2 Foreword 5 The International Nuremberg Principles Academy 7 A Forum for Dialogue 8 • Events 14 • Network and Cooperation 19 Capacity Building 25 Research 29 Publications and Resources 32 Communications 34 Organization 37 Partners and Sponsors We proudly present the second edition of the Annual Report of the International Nuremberg Principles Academy. It reflects the activities and the achieve ments of the Nuremberg Academy throughout the year of 2018. It was another year of growth for the Nu Foreword remberg Academy with an increased num ber of events and activities at a peak level. Important anniversaries such as the 70th anniversary of the judgment of the International Military Tribunal for the Far East in Tokyo and the 20th anniversary of the adoption of the Rome Statute have been reflected in the Academy’s work and activities. Major international conferences – as far as we can see the largest of their kind, dedicated to these important dates worldwide – were held in Nuremberg in May and in October. -

Nuremberg Icj Timeline 1474-1868

NUREMBERG ICJ TIMELINE 1474-1868 1474 Trial of Peter von Hagenbach In connection with offenses committed while governing ter- ritory in the Upper Alsace region on behalf of the Duke of 1625 Hugo Grotius Publishes On the Law of Burgundy, Peter von Hagenbach is tried and sentenced to death War and Peace by an ad hoc tribunal of twenty-eight judges representing differ- ent local polities. The crimes charged, including murder, mass Dutch jurist and philosopher Hugo Grotius, one of the principal rape and the planned extermination of the citizens of Breisach, founders of international law with such works as Mare Liberum are characterized by the prosecution as “trampling under foot (On the Freedom of the Seas), publishes De Jure Belli ac Pacis the laws of God and man.” Considered history’s first interna- (On the Law of War and Peace). Considered his masterpiece, tional war crimes trial, it is noted for rejecting the defense of the book elucidates and secularizes the topic of just war, includ- superior orders and introducing an embryonic version of crimes ing analysis of belligerent status, adequate grounds for initiating against humanity. war and procedures to be followed in the inception, conduct, and conclusion of war. 1758 Emerich de Vattel Lays Foundation for Formulating Crime of Aggression In his seminal treatise The Law of Nations, Swiss jurist Emerich de Vattel alludes to the great guilt of a sovereign who under- 1815 Declaration Relative to the Universal takes an “unjust war” because he is “chargeable with all the Abolition of the Slave Trade evils, all the horrors of the war: all the effusion of blood, the The first international instrument to condemn slavery, the desolation of families, the rapine, the acts of violence, the rav- Declaration Relative to the Universal Abolition of the Slave ages, the conflagrations, are his works and his crimes . -

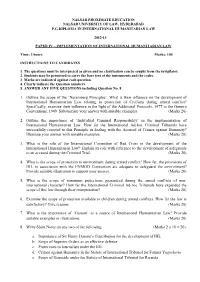

1. Outline the Scope of the 'Nuremberg Principles'. What Is

NALSAR PROXIMATE EDUCATION NALSAR UNIVERSITY OF LAW, HYDERABAD P.G.DIPLOMA IN INTERNATIONAL HUMANITARIAN LAW 2012-13 PAPER IV – IMPLEMENTATION OF INTERNATIONAL HUMANITARIAN LAW Time: 3 hours Marks: 100 INSTRUCTIONS TO CANDIDATES 1. The questions must be interpreted as given and no clarification can be sought from the invigilator. 2. Students may be permitted to carry the bare text of the instruments and the codes. 3. Marks are indicated against each question. 4. Clearly indicate the Question numbers. 5. ANSWER ANY FIVE QUESTIONS including Question No. 8 1. Outline the scope of the ‘Nuremberg Principles’. What is their influence on the development of International Humanitarian Law relating to protection of Civilians during armed conflict? Specifically, examine their influence in the light of the Additional Protocols, 1977 to the Geneva Conventions, 1949. Substantiate your answer with suitable examples. (Marks 20) 2. Outline the importance of ‘Individual Criminal Responsibility’ in the implementation of International Humanitarian Law. How far the International Ad-hoc Criminal Tribunals have successfully resorted to this Principle in dealing with the Accused of Crimes against Humanity? Illustrate your answer with suitable examples. (Marks 20) 3. What is the role of the International Committee of Red Cross in the development of the International Humanitarian Law? Explain its role with reference to the development of safeguards to an accused during the Criminal Trial. (Marks 20) 4. What is the scope of protection to environment during armed conflict? How far, the provisions of IHL in association with the ENMOD Convention are adequate to safeguard the environment? Provide suitable illustration to support your answer. -

1. Examine the Impact of the 'Nuremberg Principles' on The

NALSAR PROXIMATE EDUCATION NALSAR UNIVERSITY OF LAW, HYDERABAD P.G.DIPLOMA IN INTERNATIONAL HUMANITARIAN LAW 2009-10 PAPER IV – Implementation of International Humanitarian Law Time: 2 hours and 30 minutes Marks: 75 INSTRUCTIONS TO CANDIDATES 1. The questions to be interpreted as given and no clarification can be sought from the invigilator 2. Students may be permitted to carry the bare text of the instruments and the codes. 3. All questions carry equal marks (15 marks each) 4. Clearly indicate the Question numbers ANSWER ANY FIVE QUESTIONS 1. Examine the impact of the ‘Nuremberg Principles’ on the development of IHL in the post Geneva Conventions phase. How far, the Nuremberg Principles have facilitated the implementation of the IHL? Substantiate your answer with suitable examples. 2. Examine the scope of ‘Individual Criminal Responsibility’ as an important principle of International humanitarian law. How far this principle has been invoked at the International Plane for the effective implementation of IHL? Support your answer with suitable examples. 3. Write Short Notes on any three of the following a. Importance of Marten’s Clause b. Principle of Complimentarity c. Protections to witnesses during criminal trial d. Scope of War Crimes in the Statute of International Tribunal for Former Yugoslavia e. Scope of Crimes against in the Statute of International Tribunal for Rwanda 4. Examine the scope of ‘Rape’ as interpreted by the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda committed during the course of Non International Armed Conflict. Refer to leading case laws. 5. What is the role of the International Committee of Red Cross in the development of the International Humanitarian Law? Explain its role with reference to the development of safeguards to an accused during the Criminal Trial. -

Viewing, Reading, and Listening to the Trials in Eastern Europe Charting a New Historiography

Cahiers du monde russe Russie - Empire russe - Union soviétique et États indépendants 61/3-4 | 2020 Écritures visuelles, sonores et textuelles de la justice Introduction Viewing, reading, and listening to the trials in Eastern Europe Charting a New Historiography Nadège Ragaru Translator: Victoria Baena Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/monderusse/12009 DOI: 10.4000/monderusse.12009 ISSN: 1777-5388 Publisher Éditions de l’EHESS Printed version Date of publication: 1 July 2020 Number of pages: 297-316 ISBN: 978-2-7132-2832-2 ISSN: 1252-6576 Electronic reference Nadège Ragaru, “Viewing, reading, and listening to the trials in Eastern Europe”, Cahiers du monde russe [Online], 61/3-4 | 2020, Online since 01 July 2020, connection on 29 March 2021. URL: http:// journals.openedition.org/monderusse/12009 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/monderusse.12009 © École des hautes études en sciences sociales INTRODUCTION VIEWING, READING, AND LISTENING TO THE TRIALS IN EASTERN EUROPE Charting a New Historiography Since the end of World War II, the legal pursuit of war crimes before national and international jurisdictions has generated a vast scholarly literature.1 A broad range of multi-disciplinary writings have examined the political and diplomatic stakes of these trials, the legal professionals involved in the proceedings, the juridical advances they delivered, the establishment of proof and sentencing policies, as well as the didactic aims of postwar criminal justice.2 Within this scholarship, the Nuremberg (1945)3 and Eichmann (1960-1961)4 trials have captivated the most 1. The author wishes to thank Vanessa Voisin and Valérie Pozner for their valuable comments and suggestions on an earlier version of this introduction. -

USHMM Finding

http://collections.ushmm.org Contact [email protected] for further information about this collection United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Interview with Benjamin B. Ferencz August 26, 1994 and October 21, 1994 RG-50.030*0269 The following transcript is the result of a recorded interview. The recording is the primary source document, not this transcript. It has not been checked for spelling nor verified for accuracy. This document should not be quoted or used without first checking it against the interview. The interview is part of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum's collection of oral testimonies. Information about access and usage rights can be found in the catalog record. http://collections.ushmm.org Contact [email protected] for further information about this collection PREFACE The following oral history testimony is the result of a videotaped interview with Benjamin B. Ferencz conducted by Joan Ringelheim on August 26, 1994 on behalf of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. The interview took place in New Rochelle, NY, and is part of the United States Holocaust Research Institute's collection of oral testimonies. The reader should bear in mind that this is a verbatim transcript of spoken, rather than written prose. This transcript has been neither checked for spelling nor verified for accuracy, and therefore, it is possible that there are errors. As a result, nothing should be quoted or used from this transcript without first checking it against the taped interview. The following transcript is the result of a recorded interview. The recording is the primary source document, not this transcript. -

Pirates and Impunity: Is the Threat of Asylum Claims a Reason to Allow Pirates to Escape Justice

Pirates and Impunity: Is the Threat of Asylum Claims a Reason to Allow Pirates to Escape Justice Yvonne M. Dutton Abstract Pirates are literally getting away with murder. Modern pirates are attacking vessels, hijacking ships at gunpoint, taking hostages, and injuring and killing crew members.1 They are doing so with increasing frequency. According to the International Maritime Bureau (“IMB”) Piracy Reporting Center’s 2009 Annual Report, there were 406 pirate attacks in 2009—a number that has not been reached since 2003. Yet, in most instances, a culture of impunity reigns whereby nations are not holding pirates accountable for the violent crimes they commit. Only a small portion of those people committing piracy are actually captured and brought to trial, as opposed to captured and released. For example, in September 2008, a Danish warship captured ten Somali pirates, but then later released them on a Somali beach, even though the pirates were found with assault weapons and notes stating how they would split their piracy proceeds with warlords on land. Britain’s Royal Navy has been accused of releasing suspected pirates,7 as have Canadian naval forces. Only very recently, Russia released captured Somali pirates—after a high-seas shootout between Russian marines and pirates that had attacked a tanker carrying twenty-three crew and US$52 million worth of oil.9 In May 2010, the United States released ten captured pirates it had been holding for weeks after concluding that its search for a nation to prosecute them was futile. In fact, between March and April 2010, European Union (“EU”) naval forces captured 275 alleged pirates, but only forty face prosecution. -

An American Tragedy

[Vol.119 NUREMBERG AND VIETNAM: AN AMERICAN TRAGEDY. By TELFORD TAYLOR. Chicago: Quadrangle Books, Inc., 1970. Pp. 224. $5.95. Joseph W. Bishop, Jr.- I have very little fault to find with Professor Taylor's exposition of the law, both our own constitutional law and the international law of war, applicable to the hostilities in Vietnam. It appears accurate, lucid, and reasonable-an extraordinarily good summary, for the lay as well as the legal reader, of some extraordinarily difficult legal problems. In particular, I am in complete agreement with his conclusion that the law of war, as difficult as it may be to apply and enforce, is very much better than no law at all. Its existence has averted a great deal of suffering in the wars which have afflicted our species during the last half century or so.' I have, of course, a few caveats about some of Professor Taylor's suggestions. For example, while agreeing that it might well be preferable to try the American soldiers accused of war crimes in the Song My incident before special military commissions composed of civilian lawyers and judges, instead of before courts-martial, I have some doubt whether that could legally be done. Certainly, if I were counsel for one of the accused, I could make a strong argument that under the Uniform Code of Military Justice 2 he is entitled to trial by general court-martial, with all the protection that implies. Likewise, I have greater doubt than Professor Taylor as to the validity of the so-called "Nuremberg defense," a concept which in essence would permit an individual lawfully to refuse to obey orders to participate in training for combat in Vietnam, to go to Vietnam, or even to report for induction, on the ground that compliance with such orders would put him in a position in which he would be compelled to commit violations of the law of war.3 My trouble with the concept is that I do not believe its basic premise. -

NUREMBERG) Judgment of 1 October 1946

INTERNATIONAL MILITARY TRIBUNAL (NUREMBERG) Judgment of 1 October 1946 Page numbers in braces refer to IMT, judgment of 1 October 1946, in The Trial of German Major War Criminals. Proceedings of the International Military Tribunal sitting at Nuremberg, Germany , Part 22 (22nd August ,1946 to 1st October, 1946) 1 {iii} THE INTERNATIONAL MILITARY TRIBUNAL IN SESSOIN AT NUREMBERG, GERMANY Before: THE RT. HON. SIR GEOFFREY LAWRENCE (member for the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland) President THE HON. SIR WILLIAM NORMAN BIRKETT (alternate member for the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland) MR. FRANCIS BIDDLE (member for the United States of America) JUDGE JOHN J. PARKER (alternate member for the United States of America) M. LE PROFESSEUR DONNEDIEU DE VABRES (member for the French Republic) M. LE CONSEILER FLACO (alternate member for the French Republic) MAJOR-GENERAL I. T. NIKITCHENKO (member for the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics) LT.-COLONEL A. F. VOLCHKOV (alternate member for the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics) {iv} THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, THE FRENCH REPUBLIC, THE UNITED KINGDOM OF GREAT BRITAIN AND NORTHERN IRELAND, AND THE UNION OF SOVIET SOCIALIST REPUBLICS Against: Hermann Wilhelm Göring, Rudolf Hess, Joachim von Ribbentrop, Robert Ley, Wilhelm Keitel, Ernst Kaltenbrunner, Alfred Rosenberg, Hans Frank, Wilhelm Frick, Julius Streicher, Walter Funk, Hjalmar Schacht, Gustav Krupp von Bohlen und Halbach, Karl Dönitz, Erich Raeder, Baldur von Schirach, Fritz Sauckel, Alfred Jodl, Martin -

Filming the End of the Holocaust War, Culture and Society

Filming the End of the Holocaust War, Culture and Society Series Editor: Stephen McVeigh, Associate Professor, Swansea University, UK Editorial Board: Paul Preston LSE, UK Joanna Bourke Birkbeck, University of London, UK Debra Kelly University of Westminster, UK Patricia Rae Queen’s University, Ontario, Canada James J. Weingartner Southern Illimois University, USA (Emeritus) Kurt Piehler Florida State University, USA Ian Scott University of Manchester, UK War, Culture and Society is a multi- and interdisciplinary series which encourages the parallel and complementary military, historical and sociocultural investigation of 20th- and 21st-century war and conflict. Published: The British Imperial Army in the Middle East, James Kitchen (2014) The Testimonies of Indian Soldiers and the Two World Wars, Gajendra Singh (2014) South Africa’s “Border War,” Gary Baines (2014) Forthcoming: Cultural Responses to Occupation in Japan, Adam Broinowski (2015) 9/11 and the American Western, Stephen McVeigh (2015) Jewish Volunteers, the International Brigades and the Spanish Civil War, Gerben Zaagsma (2015) Military Law, the State, and Citizenship in the Modern Age, Gerard Oram (2015) The Japanese Comfort Women and Sexual Slavery During the China and Pacific Wars, Caroline Norma (2015) The Lost Cause of the Confederacy and American Civil War Memory, David J. Anderson (2015) Filming the End of the Holocaust Allied Documentaries, Nuremberg and the Liberation of the Concentration Camps John J. Michalczyk Bloomsbury Academic An Imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc LONDON • OXFORD • NEW YORK • NEW DELHI • SYDNEY Bloomsbury Academic An imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc 50 Bedford Square 1385 Broadway London New York WC1B 3DP NY 10018 UK USA www.bloomsbury.com BLOOMSBURY and the Diana logo are trademarks of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc First published 2014 Paperback edition fi rst published 2016 © John J. -

UNDERSTANDING POWER the INDISPENSABLE CHOMSKY Edited by Peter R

THE FOOTNOTES FOR: UNDERSTANDING POWER THE INDISPENSABLE CHOMSKY Edited by Peter R. Mitchell and John Schoeffel. Preface 1. For George Bush's statement, see "Bush's Remarks to the Nation on the Terrorist Attacks," New York Times, September 12, 2001, p. A4. For the quoted analysis from the New York Times's first "Week in Review" section following the September 11th attacks, see Serge Schmemann, "War Zone: What Would ‘Victory’ Mean?," New York Times, September 16, 2001, section 4, p. 1. Understanding Power: Preface Footnote Chapter One Weekend Teach-In: Opening Session 1. On Kennedy's fraudulent "missile gap" and major escalation of the arms race, see for example, Fred Kaplan, Wizards of Armageddon, New York: Simon & Schuster, 1983, chs. 16, 19 and 20; Desmond Ball, Politics and Force Levels: The Strategic Missile Program of the Kennedy Administration, Berkeley: University of California Press, 1980, ch. 2. On Reagan's fraudulent "window of vulnerability" and "military spending gap" and the massive military buildup during his first administration, see for example, Jeff McMahan, Reagan and the World: Imperial Policy in the New Cold War, New York: Monthly Review, 1985, chs. 2 and 3; Franklyn Holzman, "Politics and Guesswork: C.I.A. and D.I.A. estimates of Soviet Military Spending," International Security, Fall 1989, pp. 101-131; Franklyn Holzman, "The C.I.A.'s Military Spending Estimates: Deceit and Its Costs," Challenge, May/June 1992, pp. 28-39; Report of the President's Commission on Strategic Forces, Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office, April 1983, especially pp. 7-8, 17, and Brent Scowcroft, "Final Report of the President's Commission on Strategic Forces," Atlantic Community Quarterly, Vol.