Number 36 Landmarkings

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

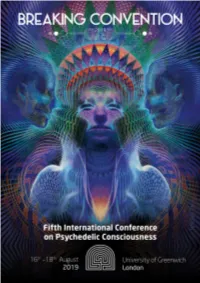

BC2019-Printproginccovers-High.Pdf

CONTENTS Welcome with Acknowledgements 1 Talk Abstracts (Alphabetically by Presenter) 3 Programme (Friday) 32–36 Programme (Saturday) 37–41 Programme (Sunday) 42–46 Installations 47–52 Film Festival 53–59 Entertainment 67–68 Workshops 69–77 Visionary Art 78 Invited Speaker & Committee Biographies 79–91 University Map 93 Area Map 94 King William Court – Ground Floor Map 95 King William Court – Third Floor Map 96 Dreadnought Building Map (Telesterion, Underworld, Etc.) 97 The Team 99 Safer Spaces Policy 101 General Information 107 BREAK TIMES - ALL DAYS 11:00 – 11:30 Break 13:00 – 14:30 Lunch 16:30 – 17:00 Break WELCOME & ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS WELCOME & ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS for curating the visionary art exhibition, you bring that extra special element to BC. Ashleigh Murphy-Beiner & Ali Beiner for your hard work, in your already busy lives, as our sponsorship team, which gives us more financial freedom to put on such a unique event. Paul Callahan for curating the Psychedelic Cinema, a fantastic line up this year, and thanks to Sam Oliver for stepping in last minute to help with this, great work! Andy Millns for stepping up in programming our installations, thank you! Darren Springer for your contribution to the academic programme, your perspective always brings new light. Andy Roberts for your help with merchandising, and your enlightening presence. Julian Vayne, another enlightening and uplifting presence, thank you for your contribution! To Rob Dickins for producing the 8 circuit booklet for the welcome packs, and organising the book stall, your expertise is always valuable. To Maria Papaspyrou for bringing the sacred feminine and TRIPPth. -

15Aprhoddercat Autumn21 FO

FICTION 3 CRIME & THRILLERS 35 NON-FICTION 65 CORONET 91 HODDER STUDIO 99 YELLOW KITE & LIFESTYLE 117 sales information 136 FICTION N @hodderbooks M HodderBooks [ @hodderbooks July 2021 Romantic Comedy . Contemporary . Holiday WELCOME TO FERRY LANE MARKET Ferry Lane Market Book 1 Nicola May Internationally bestselling phenomenon Nicola May is back with a brand new series. Thirty-three-year-old Kara Moon has worked on the market’s flower stall ever since leaving school, dreaming of bigger things. When her good-for-nothing boyfriend cheats on her and steals her life savings, she finally dumps him and rents out her spare room as an Airbnb. Then an anonymous postcard arrives, along with a plane ticket to New York. And there begins the first of three trips of a lifetime, during which she will learn important lessons about herself, her life and what she wants from it – and perhaps find love along the way. Nicola May is a rom-com superstar. She is the author of a dozen novels, all of which have appeared in the Kindle bestseller charts. The Corner Shop in Cockleberry Bay spent 11 weeks at the top of the Kindle bestseller chart and was the overall best-selling fiction ebook of 2019 across the whole UK market. Her books have been translated into 12 languages. 9781529346442 • £7.99 Exclusive territories: Publicity contact: Rebecca Mundy B format Paperback • 384pp World English Language Advance book proofs available on request eBook: 9781529346459 • £7.99 US Rights: Hodder & Stoughton Author lives in Ascot, Berkshire. Author Audio download: Translation Rights: is available for: interview, features, 9781529346466 • £19.99 Lorella Belli, LBLA festival appearances, local events. -

Sarah Driver Presents the Huntress: Sea (Ages 9+) No Place Like Home Sarah Driver Kapka Kassabova & Jan Rüger in Conversation with Joshua Jelly-Schapiro

Presents 8th - 11th June 2017 Happy, Healthy, Home? at The Bedford Pub, 77 Bedford Hill, Balham, SW12 9HD balhamliteraryfestival.co.uk Welcome to the Presents Happy, Healthy, Home? Working on the second Balham literary festival set me to musing about the things that make Balham an inspiring 8th - 11th June 2017 place to call home. The second world war of course features in everyone’s memories – the tragedy at the underground station of 14th October 1940, the dark rumour that Hitler had planned to set up shop in Du Cane Court. Our neighbourhood has welcomed new arrivals from around the world, including the Polish community and the Windrush generation. Our religious worshippers have founded a mosque, a temple and a synagogue as Pop-up bookshop all weekend at The Bedford Monday - Saturday well as churches. There are cultural landmarks, too – the Lido, the Bedford pub itself – and proximity to important 9.30 - 17.30 health centres past and present, including St George’s Hospital and the former asylum at Tooting Bec. Edward Dulwich Books is an award-winning independent Thomas and Thomas Hardy both have connections to the area, marking our literary heritage. We have a café bookshop based in West Dulwich. We were shortlisted Sunday culture and a relaxed, friendly vibe which makes this place so popular. for Best Independent Bookshop in London in the 11.00 - 16.00 British Book Awards 2017 I wanted to gather up all these threads and bring together writers – many of whom are South Londoners – to explore themes of war, migration, exile, creating a homeland, home cooking, swimming, mental health and neurosurgery, literature, singer songwriting, the Caribbean today, the lands at the edges of Western Europe, Dulwich Books is at number 6 Croxted Road, Order a book SE21 8SW. -

Download the 2015 Programme

LEDBURY POETRY FESTIVAL 2O15 03–12 July 2015 Programme poetry-festival.co.uk @ledburyfest Ledbury Poetry Festival 3 -12 July 2015 Thank you to all the generous and enthusiastic people who give their time and energy to making the Festival the jam-packed, fun-filled, world-class poetry event that it is. Thank you to all our volunteers who help with administration, stewarding, hospitality, accommodation, driving and much more. Thanks also to all our sponsors and supporters. This Festival grew out of its community and it remains a community celebration. Community Programme Poets Brenda Read Brown and Sara-Jane Arbury work all year round with people who may never be able to attend a Festival event, who have never attempted creative writing before, or have never taken part in any cultural activity. The impact this work can have is astounding. The Community Programme reaches out to people facing social exclusion due to physical or mental health issues, disability or learning challenges and engages them in life-affirming ways with poetry and the creative process. See the Mary and Joe event on Sunday 12th July. Recent projects have included poetry writing in doctors’ surgeries and hospital waiting rooms, and with vulnerable women at a women’s shelter. Opportunities for self-expression in these communities are hugely rewarding for all involved. “You’ve woken something up in me!” said one participant. This is only possible due to funding from the Esmée Fairbairn Foundation, Garfield Weston Foundation, Herefordshire Community Foundation and Sylvia Adams Charitable Trust. Poets in Schools All year round the Festival sends skilled and experienced poets into schools across Herefordshire to enable pupils to read, write and thoroughly enjoy poetry. -

Hodder & Stoughton Spring 2021 Translation Rights Guide

Hodder & Stoughton Spring 2021 Translation Rights Guide TABLE OF CONTENTS 2021 SPRING HIGHLIGHTS……………………………………………………………………….…1 FICTION………………………………………………………………………………………………………2 CRIME & THRILLER……………………………………………………………………………………16 LITERARY……………………………………………………………………………………………….…23 NON-FICTION……………………………………………………………………………………………25 LIFESTYLE …………………………………………………………………………………………………41 FOOD………………………………………………………………………………………………..………45 FOR MORE INFORMATION PLEASE CONTACT: Rebecca Folland, Rights Director: [email protected] Melis Dagoglu, Head of Rights: [email protected] Grace McCrum, Senior Rights Manager: [email protected] More information on our Partner Agents: Albania, Bulgaria & Macedonia - Anthea Agency - [email protected] Brazil - Riff Agency- [email protected] China and Taiwan - The Grayhawk Agency - [email protected] Czech Republic & Slovakia - Kristin Olson Agency- [email protected] Greece - OA Literary Agency - [email protected] Hungary, Croatia, Serbia, Slovenia - Katai and Bolza Literary Agency - [email protected] Indonesia - Maxima Creative Agency – [email protected] Japan - Tuttle-Mori Agency - [email protected] Korea - Eric Yang Agency - [email protected] Romania - Simona Kessler International - [email protected] Thailand and Vietnam - The Grayhawk Agency - [email protected] Turkey - AnatoliaLit Agency - [email protected] 2021 SPRING HIGHLIGHTS FICTION: THE FAIR BOTANISTS by Sara Sheridan (p.2) A bewitching and immersive story set in Edinburgh centring around the highly sought after bloom, the Agave Americana plant, which has the city stirring with excitement and secrets ready to un- fold…we’ve teamed up with the Edinburgh Botanical Gardens, and can’t wait for readers to fall in love with these characters and the city. SEVENTEEN by John Brownlow (p.16) An electrifying thriller about hitman, Seventeen, who is assigned to kill his predecessor...until sud- denly the hunter becomes the hunted. -

Highlights London Book Fair 2017 Highlights

Highlights London Book Fair 2017 Highlights Welcome to our 2017 International Book Rights Highlights For more information please go to our website to browse our shelves and find out more about what we do and who we represent. Contents Fiction Literary/Upmarket Fiction 1 - 7 Commercial Fiction 8- 16 Crime, Suspense, Thriller 16 -23 Non-Fiction Biography, Memoir and Letters 24 - 26 Economics, History and Poliitics 27 - 33 Nature 34 - 38 Society and Philosophy 39 - 42 Centenary Celebrations 43 - 44 Paperback Spotlight 45 Film and TV News 46 Sub-Agents 47 Agents US Rights: Veronique Baxter; Jemima Forrester; Georgia Glover; Anthony Goff (AG); Andrew Gordon (AMG); Lizzy Kremer; Harriet Moore; Caroline Walsh; Alice Williams Film & TV Rights: Nicky Lund; Clare Israel; Georgina Ruffhead Translation Rights: Alice Howe: [email protected] Direct: Brazil; France; Germany; Netherlands Subagented: Italy Emma Jamison: [email protected] Direct: Arabic; Croatia; Estonia; Greece; Israel; Slovenia; Spain and Spanish in Latin America; Ukraine Sub-agented: Czech Republic; Poland; Romania; Russia; Scandinavia; Slovakia; Turkey Emily Randle: [email protected] Direct: Afrikaans; all Indian languages; Portugal; Vietnam; Wales; plus miscellaneous requests Subagented: China; Bulgaria; Hungary, Indonesia; Japan; Korea; Serbia; Taiwan; Thailand Margaux Vialleron: [email protected] All rights enquiries Contact t: +44 (0)20 7434 5900 f: +44 (0)20 7437 1072 www.davidhigham.co.uk Safe Ryan Gattis A riveting, cinematic new novel from Ryan Gattis, which Paula Hawkins has described as ‘a thrilling heist novel with a big, beating heart’ Ricky ‘Ghost’ Mendoza, Jr. is trying to be good. His past is distorted by violence: as a teenager he was a gangbanger, addict and killer until he got out. -

Peninsula 2012 Visitation

PENINSULA ALEX GARLAND, ROBERT MACFARLANE, JAY GRIFFiths, ROY WILKINSon, TOBY BaRLOW, KATHLEEN JAMIE & JAMES ROBERTSON VISITATION 2012 Peninsula 2012 VISITATION It’s 2012 – Olympic Year. As crowds, competition In the end we managed to secure contributions and corporate branding descend on East London, from an immense and varied collection of writers. it seems apt that this, the third annual edition Booker nominees, New York Times bestsellers, of Peninsula, should reflect the transformation Royal Society of Literature Fellows and the of the capital and the summer’s influx of recipients of a whole host of other plaudits sent us visitors. Hopefully, however, what we have great writing, the writing that now fills these pages. created will retain continued relevance long after the Olympic village has been left behind It wasn’t all fudge and business, however. We by the world’s athletes. sought the opinions of the clergy, the police and the family behind one of London’s most unusual tourist Overseeing the project, Craig Taylor was forced attractions. As if that wasn’t enough, things then to fight the pull of the capital and attend early- got strange in the bowels of Bodmin Jail, where morning meetings deep in Cornwall after sleepless what should have been a straightforward interview nights spent flying west along the Cornish Main escalated into a paranormal commune with the Line. Over machine-stale coffee, plans were deceased, distant relatives of the editorial team. conceived, lists were drawn up and within a couple of hours Craig would leave us and climb tiredly At this point it is tempting to include a dictionary back on the train to the city, no doubt rueing his definition, so as to demonstrate the possibilities commitment to these Cornish visitations. -

Nature and Travel Writing Handbook

MA in Nature and Travel Writing Bath Spa University Course Handbook 2021-22/23 1 | P a g e The MA in Nature and Travel Writing at Bath Spa University is designed for writers who wish to develop their skills and experience in creative non-fiction, inspired by the natural world and contemporary travelling. This course will explore these topics and students will be immersed in a literature that covers travel writing, nature writing and examples from a range of other genres, to provide a context, backdrop and perspective to their own work. They will also receive practical advice, and do specific assignments, on how to get their work published, from a range of sources including their tutors and other professionals working in the field. The main purpose of this handbook is to answer any queries you might have about at this MA programme. The Handbook contains essential information about your course structure, support and assessments. Please take time to get acquainted with these pages. NOTE: This is a low-residency course and much of the tuition will take place in residential sessions away from campus and through distance learning. However, the course is based at Bath Spa University’s historic Corsham Court campus, where we also hold the first residential in early October. IMPORTANT NOTE – Full-time or Part-time? Since the course began in 2015, we have seen a shift from the majority of students doing the MA full-time over one year, to doing it part-time over two years. The vast majority of students (19 of 20 in the current intake) either start part-time or switch to part-time after one term. -

Back to the Future: "The New Nature Writing," Ecological Boredom, and the Recall of the Wild

This is a repository copy of Back to the Future: "The New Nature Writing," Ecological Boredom, and the Recall of the Wild. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/96981/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Huggan, GDM (2016) Back to the Future: "The New Nature Writing," Ecological Boredom, and the Recall of the Wild. Prose Studies, 38 (2). pp. 152-171. ISSN 0144-0357 https://doi.org/10.1080/01440357.2016.1195902 (c) 2016, Informa UK Limited trading as Taylor & Francis Group. This is an Accepted Manuscript of an article published by Taylor & Francis in Prose Studies on 12 October 2016, available online: https://doi.org/10.1080/01440357.2016.1195902 Reuse Unless indicated otherwise, fulltext items are protected by copyright with all rights reserved. The copyright exception in section 29 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 allows the making of a single copy solely for the purpose of non-commercial research or private study within the limits of fair dealing. The publisher or other rights-holder may allow further reproduction and re-use of this version - refer to the White Rose Research Online record for this item. Where records identify the publisher as the copyright holder, users can verify any specific terms of use on the publisher’s website. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Back to the Future: The “New Nature Writing,” Ecological Boredom, and the Recall of the Wild Abstract The “new nature writing” has been seen as a response, especially in the UK, to the growing sense that earlier paradigms of nature and nature writing are no longer applicable to current geographical and environmental conditions. -

Hodder & Stoughton Spring 2021 Translation Rights Guide

Hodder & Stoughton Spring 2021 Translation Rights Guide TABLE OF CONTENTS 2021 SPRING HIGHLIGHTS……………………………………………………………………….…1 FICTION………………………………………………………………………………………………………2 CRIME & THRILLER……………………………………………………………………………………16 LITERARY……………………………………………………………………………………………….…23 NON-FICTION……………………………………………………………………………………………25 LIFESTYLE …………………………………………………………………………………………………41 FOOD………………………………………………………………………………………………..………45 FOR MORE INFORMATION PLEASE CONTACT: Rebecca Folland, Rights Director: [email protected] Melis Dagoglu, Head of Rights: [email protected] Grace McCrum, Senior Rights Manager: [email protected] More information on our Partner Agents: Albania, Bulgaria & Macedonia - Anthea Agency - [email protected] Brazil - Riff Agency- [email protected] China and Taiwan - The Grayhawk Agency - [email protected] Czech Republic & Slovakia - Kristin Olson Agency- [email protected] Greece - OA Literary Agency - [email protected] Hungary, Croatia, Serbia, Slovenia - Katai and Bolza Literary Agency - [email protected] Indonesia - Maxima Creative Agency – [email protected] Japan - Tuttle-Mori Agency - [email protected] Korea - Eric Yang Agency - [email protected] Romania - Simona Kessler International - [email protected] Thailand and Vietnam - The Grayhawk Agency - [email protected] Turkey - AnatoliaLit Agency - [email protected] 2021 SPRING HIGHLIGHTS FICTION: THE FAIR BOTANISTS by Sara Sheridan (p.2) A bewitching and immersive story set in Edinburgh centring around the highly sought after bloom, the Agave Americana plant, which has the city stirring with excitement and secrets ready to un- fold…we’ve teamed up with the Edinburgh Botanical Gardens, and can’t wait for readers to fall in love with these characters and the city. SEVENTEEN by John Brownlow (p.16) An electrifying thriller about hitman, Seventeen, who is assigned to kill his predecessor...until sud- denly the hunter becomes the hunted. -

Highlights London Book Fair 2016 Highlights

Highlights London Book Fair 2016 Highlights Welcome to our 2016 International Book Rights Highlights For more information please go to our website to browse our shelves and find out more about what we do and who we represent. Contents Fiction Literary and Upmarket Fiction 1 - 7 Crime and Thrillers 8 - 13 Commercial Fiction 14 - 24 Non-Fiction Anthropology and History 25 - 29 Essays, Biography and Memoirs 30 - 35 Natural World 36 - 38 Roald Dahl Centenary 39 James Herriot Centenary 40 2016 Highlights 41 Sub-Agents 42 Agents US Rights: Veronique Baxter; Toby Eady; Georgia Glover; Anthony Goff (AG); Andrew Gordon (AMG); Lizzy Kremer; Caroline Walsh; Alice Williams; Jessica Woollard Film & TV Rights: Nicky Lund; Georgina Ruffhead Translation Rights: Alice Howe: [email protected] Direct: Brazil; France; Germany; Netherlands Sub-agented: Italy Emma Jamison: [email protected] Direct: Arabic; Croatia; Estonia; Greece; Israel; Latvia; Lithuania; Portugal; Scandinavia; Slovenia; Spain and Spanish in Latin America; Ukraine Sub-agented: Czech Republic; Hungary; Poland; Romania; Russia; Slovakia; Turkey Emily Randle: [email protected] Direct: Afrikaans; Georgian; all Indian languages; Vietnam; Wales; plus miscellaneous requests Sub-agented: China; Bulgaria; Indonesia; Japan; Korea; Serbia; Taiwan; Thailand Camilla Dubini: [email protected] Audio rights: all territories Contact t: +44 (0)20 7434 5900 f: +44 (0)20 7437 1072 www.davidhigham.co.uk The Power Naomi Alderman An impressive and original novel investigating the roots of power and how sometimes it only takes a spark to ignite the greatest challenges in society A girl in the deep South overcomes her abuser. A Nigerian man films a woman fighting back in a supermarket. -

Penguin General Spring Catalogue 2021

1 CONTENTS January 3 February 8 March 19 April 28 May 36 June 41 July 48 Paperbacks 50 Penguin General Books 20 Vauxhall Bridge Road London SW1V 2SA TEL: 0207139 3000 For details on US, translation, serial and film and TV rights please visit: www.penguinrights.co.uk For up-to-the-minute information visit: www.penguincatalogue.co.uk www.penguin.co.uk 2 JANUARY 2021 3 Hamish Hamilton Consequences of Capitalism Manufacturing Discontent and Resistance Noam Chomsky and Marv Waterstone An essential primer on capitalism, politics and how the world works, based on the hugely popular undergraduate lecture series 'What is Politics?' Is there an alternative to capitalism? In this landmark text Chomsky and Waterstone chart a critical map for a more just and sustainable society. 'Covid-19 has revealed glaring failures and monstrous brutalities in the current capitalist system. It represents both a crisis and an opportunity. Everything depends on the actions that people take into their own hands.' How does politics shape our world, our lives and our perceptions? How much of 'common sense' is actually driven by the ruling classes' needs and interests? And how are we to challenge the capitalist structures that now threaten all life on the planet? Consequences of Capitalism exposes the deep, often unseen connections between neoliberal 'common sense' and structural power. In making these linkages, we see how the current hegemony keeps social justice movements divided and marginalized. And, most importantly, we see how we can fight to overcome these divisions. Noam Chomsky is the bestselling author of over 100 influential political books, including Hegemony or Survival, January 2021 Imperial Ambitions, Failed States, Interventions, What We Say 9780241482612 Goes, Hopes and Prospects, Making the Future, On Anarchism, Royal Octavo Masters of Mankind and Who Rules the World.