Fpuscholarworks

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Organs of the Iberian Peninsular — Part III

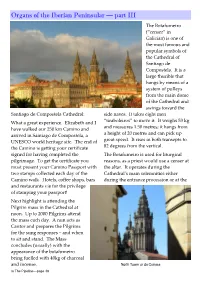

Organs of the Iberian Peninsular — part III The 5otafumeiro 26censer7 in 8alician3 is one of the most famous and popular symbols of the Cathedral of Santiago de Compostela. It is a large thurible that hangs by means of a system of pulleys from the main dome of the Cathedral and swings toward the Santiago de Compostela Cathedral: side naves. It takes eight men What a great experience. Elizabeth and I 6tiraboleiros7 to move it. It weighs 3 kg have walked our 250 km Camino and and measures 1. 0 metres; it hangs from arrived in Santiago de Compostela, a a height of 20 metres and can pick up UNESCO world heritage site. The end of great speed. It rises in both transepts to the Camino is ge(ing your certi*cate 82 degrees from the vertical. signed for having completed the The 5otafumeiro is used for liturgical pilgrimage. To get the certi*cate you reasons, as a priest would use a censer at must present your Camino Passport with the altar. It operates during the two stamps collected each day of the Cathedral’s main solemnities either Camino walk. ,otels, co-ee shops, bars during the entrance procession or at the and restaurants vie for the privilege of stamping your passport. Next highlight is a(ending the Pilgrim mass in the Cathedral at noon. Up to 2000 Pilgrims a(end the mass each day. A nun acts as Cantor and prepares the Pilgrims for the sung responses 0 and when to sit and stand. The 1ass concludes 2usually3 with the appearance of the botafumeiro being fuelled with 40kg of charcoal and incense. -

Alternative Ritual Conclusions on the Camino De Santiago

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University Religious Studies Theses Department of Religious Studies Spring 4-11-2016 Embodied Contestation: Alternative Ritual Conclusions on the Camino de Santiago Clare Van Holm Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/rs_theses Recommended Citation Van Holm, Clare, "Embodied Contestation: Alternative Ritual Conclusions on the Camino de Santiago." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2016. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/rs_theses/50 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Religious Studies at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Religious Studies Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EMBODIED CONTESTATION: ALTERNATIVE RITUAL CONCLUSIONS ON THE CAMINO DE SANTIAGO by CLARE VAN HOLM Under the Direction of Kathryn McClymond, PhD ABSTRACT Despite its nearly thousand year history as a Christian penitent ritual, the Camino de Santiago pilgrimage has undergone rapid transformation in the last three decades, attracting a specific community of people who see themselves as “authentic” Camino pilgrims. Upon arrival at the shrine of Santiago, the traditional end of the pilgrimage route, many pilgrims express feelings of dissatisfaction. Drawing upon field research and interviews, this paper analyzes the practices of pilgrims along the Camino de Santiago route, at the shrine in Santiago de Compostela, and at the alternative conclusion site in the Galician coastal town of Finisterre. I argue that pilgrim dissatisfaction relates to pilgrim experiences in Santiago that are incongruous with their pilgrimage up until that point. In response, pilgrims have created alternative ritual conclusions that more closely relate to their experience on the Camino route and affirm their identity as “authentic” pilgrims. -

The Camino De Santiago IV

The Camino de Santiago IV In 1491, Finisterre was thought to be the end of the earth. During the Middle Ages, many pilgrims who completed their pilgrimage at the cathedral in Santiago de Compostela would continue their walk, an additional 40 miles or so, to arrive here at the northernmost tip of Spain to look out over the Atlantic, nothing but endless ocean. This was as far as they could walk in this direction; this was their end of the earth. They must have wondered. In 2000, after completing my own pilgrimage, I took a bus to the base of those very same ocean-side bluffs and hiked up their sides so that I, too, could look at what they saw. I sat there for hours, looking. I also wondered. I don’t know what a religious experience is, and for this reason, I cannot say I have ever had such an experience, but I do know that those hours spent looking over the ocean from the end of the earth were memorable ones, hours that will never be erased until I am gone. Perhaps it was the afterglow of accomplishment of having walked 450 miles, perhaps it was the relief I felt because I no longer had to force myself to strap on a backpack and undertake yet another nine-hour walk, or perhaps I was simply on holiday. I do not know. Perhaps it was the stillness of the day or the rustle of the waves below, the touch of salt in the air, or the joyful shriek of the gull. -

Camino Portuguese Classic

www.ultreyatours.com ULTREYA TOURS [email protected] +1 917 677 7470 CAMINO PORTUGUESE CLASSIC The Camino how it used to be. The Portuguese Way Premium follows the traditional Portuguese Way from Tui at the Portuguese border, 114 km into Santiago de Compostela. This means you get to visit two different countries, get your Compostela, visit some of the most historical places and... escape the crowds! Although the Portuguese Way is growing in popularity, 70% of pilgrims still choose the French Way. So if you are looking for a bit more peace and quiet, wonderful accommodation, delicious food, stunning views, easier walking days, the proximity of the beach and the possibility to enjoy a thermal bath after a walking day this is the tour for you. But shhh let’s keep this a secret between us and let us guide you through the best of the Portuguese Way. PRICE & DATES FACT FILE Can be organized on request for any number of participants Accommodation Luxurious on the dates of your choice - subject to availability and price Manors & 4 to 5* Hotels fluctuations. Total Walking Distance 114 km €1550 per person Duration 8 days / 7 nights • Single room supplement: +€490 per room Starts Tui • No dinners discount: -€140 per person Stops Valença, Porriño, Redondela, Pontevedra, Caldas de • No luggage transfers discount: -€20 per person Reis, Padrón • Guaranteed Botafumeiro: +€300 Ends Santiago de Compostela • Accompanying Guide for the duration of the tour: +€1300 • Extra night in the 4* San Francisco Monumental Hotel: +€200 per room (dinner not included) -

A Pilgrimage on the Camino De Santiago. Boulder, Colorado: Pilgrim’S Process, Inc

Lo N a t io n a l U n iv e r s it y o f I r e l a n d M a y n o o t h IN D efence o f the R e a l m : Mobility, Modernity and Community on the Camino de Santiago Keith Egan A pril 2007 A Dissertation subm itted to the D epartm ent of A nthropology in FULFILLMENT OF THE DEGREE OF PH. D. Supervisor: Professor Law rence Taylor Table of C ontents I ntroduction “I came here for the magic” ......................................................................... 1 C h a p t e r o n e From communitas to ‘Caminotas’ ............................................................ 52 C h a p t e r t w o Rites of massage ...................................................................................... 90 C hapter three Into the West.................................................................................................. 129 C h a p t e r f o u r Changes and other improvements ............. 165 C hapter five Negotiating Old Territories ................................................................... 192 Ch apter six Economies of Salvation ......................................................................... 226 C o n c l u s io n Mobility, Modernity, Community ............................................................ 265 Bibliography ...................................................................................... 287 T a b l e o f F ig u r e s Figure 1 The Refuge at Manjarin........................................ 3 Figure 2 Map of the French Way of the Camino de Santiago........................................10 Figure 3 Map showing alternative routes to Santiago.....................................................11 Figure 4 Certificate of Completion (Compostela).........................................................19 Figure 5 Official Pilgrim Passport of the Irish Society of the Friends of St, James 21 Figure 6 A pilgrim displays her collection of sellos in Santiago................................... 22 Figure 7 Official Pilgrim Passport of Les Amis du Chemin de Saint-Jacques............. -

Mondariz - Vigo - Santiago a Brief History of Galicia’S Edwardian Tourist Boom Booth Line

Mondariz - Vigo - Santiago a brief history of galicia’s Edwardian tourist boom Booth Line. r.M.S. antony Mondariz - Vigo - Santiago a brief history of galicia’s Edwardian tourist boom KIRSTY HOOPER Edita Fundación Mondariz Balneario Dirección editorial Sonia Montero Barros Texto Kirsty Hooper Realización editorial Publitia Imágenes XXXXXX I.S.B.N. 978-XXXXXXX Depósito Legal X-XXX-2013 Prohibida la reproducción total o parcial de esta obra mediante impresión, fotocopia, microfilm o cualquier otro sistema, sin permiso por escrito del autor. DRAFT Prologue to Mondariz, Vigo, Santiago. this delightful book gives a wonderful insight into the Edwardian tourist industry and the early promotion of the treasures of galicia in Britain. it points not only to the wonderful cultural and natural heritage on offer but emphasises the quality of the experience and in particular the hospitality received by visitors to Mondariz. Wind the clock forward one hundred years or so and we find the treasures are still ex- tant though the competition for tourism has increased substantially across the globe. From my own experience a recent stay at Balneario de Mondariz perfectly encapsulates all the favourable comments reflected in this book. the conservation of the cultural and natural heritage is of fundamental importance to the well-being of society. the national trust in England, Wales and northern ireland, a non-governmental organisation founded in 1895, is an exemplar in this respect, having today over 4 million members and employing 6000 staff and over 70,000 volunteers. its properties receive over 19 million visitors each year. in galicia the beginnings of such an organisation, in this case tesouros de galicia, is a brilliant and much needed concept and the hope is that, in time, it will spread to the whole of Spain. -

12 Recommended Camino De Santiago Tours 2021 Holy Year by Eatour Specialist

Visit us 12 Recommended Camino de Santiago Tours 2021 Holy Year by EATour Specialist / What Camino de Santiago Tour should I do? Here we will recommend some Camino de Santiago Tours to consider for your next trip. Read More What is the Jacobean Year? Whenever St James´s day (25th July) falls on a Sunday, the cathedral announces it a Holy or Jubilee Year (Xacobeo in the Galician Language). This happens with a regular cadence of 6-5-6-11 years (The last Holy Year was 2010). Next year will be a special year for the city of Santiago de Compostela and the St James Way since they will be celebrating the Holy Year 2021 (Xacobeo). The celebration of each Holy Year grants indulgence to all those faithful who voluntarily meet the following conditions: Visit the Santiago de Compostela Cathedral, in Galicia, Spain. Pray regularly. It is also highly recommended to attend the Holy Mass in / Santiago de Compostela Cathedral. Receive the sacraments of penance and communion in the fifteen days prior to or after visiting the Santiago de Compostela Cathedral. Furthermore, people usually access the cathedral through the Holy Door which only opens on this occasion. If you are lucky during mass at the cathedral the priest (takes quite a few!) will swing on occasion the "Botafumeiro" (An XXL incense burner). It swings up high from nave to nave and weights about 120 pounds! This was to clean the smell in the air since there are so many pilgrims attending the mass. https://youtu.be/MYqfQXPGemA The Camino de Santiago walk is a great way to enjoy / the outdoors following along the ancient Pilgrimage way passing through quaint historic villages, green landscapes, etc.. -

Basic Spanish for the Camino

BASIC SPANISH FOR THE CAMINO A Pilgrim’s Introduction to the Spanish Language and Culture American Pilgrims on the Camino www.americanpilgrims.org Northern California Chapter [email protected] February 1, 2020 Bienvenido peregrino Leaving soon on your Camino and need to learn some Spanish basics? Or perhaps you already know some Spanish and just need a refresher and some practice? In any case, here is a great opportunity to increase your awareness of the Spanish language and to prepare for your Camino and the transition into Spanish culture. Our meetings will focus on the language challenges that, as a pilgrim, you are likely to encounter on the Camino. While we will talk about culture, history, food, wine and many other day-to-day aspects of Spanish life, our objective will be to increase your language skills. Familiarity with the Spanish spoken in Spain will make the cultural transition easier for you and ultimately pay off with more satisfying human interactions along the Camino. Our meetings will be informal, in a comfortable environment and geared to making the review of Spanish an enjoyable experience. Buen Camino Emilio Escudero Northern California Chapter American Pilgrims on the Camino www.americanpilgrims.org TABLE OF CONTENTS Day 1 Agenda . i Day 2 Agenda . ii Day 3 Agenda . iii 01 - The Communities, Provinces and Geography of Spain . 1 02 - Spain - A Brief Introduction . 3 03 - A Brief History of Spain and the Camino de Santiago . 5 04 - Holidays and Observances in Spain 2020 . 11 05 - An Overview of the Spanish Language . 12 06 - Arabic Words Incorporated into Spanish . -

Pilgrimage and Postminimalism in Joby Talbot's Path Of

PILGRIMAGE AND POSTMINIMALISM IN JOBY TALBOT’S PATH OF MIRACLES by JOY ELIZABETH MEADE Under the Direction of DANIEL BARA ABSTRACT Joby Talbot’s Path of Miracles is a seventy-minute a cappella choral masterwork that portrays the experience of a pilgrim traveling the Camino de Santiago. Composed in 2005 on commission from Nigel Short for his professional choir Tenebrae, Path of Miracles is a modern- day soundtrack of this enduring pilgrimage. This paper examines Path of Miracles from three perspectives: as a representation of pilgrimage, as a reflection of the sacred and secular aspects of the Camino de Santiago, and as an example of a postminimalism in a choral work. Chapter 2 studies Path of Miracles as a musical depiction of common pilgrimage experiences as explained by anthropologists. Modern pilgrimage scholarship examines a person’s motivation to take a pilgrimage, his or her separation from daily life and social status, the re-shaping of a pilgrim’s identity along the journey, the physical effect of constant walking on the mind and body, and the re-entrance of the pilgrim into society. Path of Miracles represents these stages of pilgrimage musically. Additionally, Chapter 2 demonstrates how Path of Miracles is a modern-day, musical depiction of the French route, and this chapter will explore how the piece serves as a musical guidebook, depicting the landscape, cathedrals, cultures, people and sounds found on the Camino Frances. Chapter 3 examines the sacred and secular musical elements found in Path of Miracles, and how these elements portray the dichotomy of religious and non-religious aspects of the Camino’s history. -

Pilgrims Reflect on the Walking the 500-Mile Camino De Santiago

Pilgrims reflect on the walking the 500-mile Camino de Santiago If life is a journey, then the Camino de Santiago is the ultimate metaphor. “A friend once told me that once you realize everything you need in life fits in a pack on your back, life becomes a lot easier, except for the realization that a lot of what we have in life is a burden,” said Matt Shepardson, who has walked the Camino three times in the last seven years. “The most prominent experience I’ve ever had in my life is hiking the Camino,” Shepardson, 57, a retired airline pilot who lives northwest of Philadelphia, told Our Sunday Visitor. Shepardson said he hopes to walk The Way of St. James for a fourth time. “It’s become such a part of my existence, there isn’t a day that goes by that I don’t think about something related to the Camino,” he said. A group of hikers walks down steps along the trail of the Camino de Santiago. Photo courtesy of Greg Daly For more than a thousand years, pilgrims have walked hundreds of miles through the countryside in France, Western Europe and the Iberian Peninsula to venerate what tradition holds are the relics of St. James the Great in the Santiago de Compostela Cathedral in the Galicia region of Spain. Shortly after the relics were discovered in the ninth century, the Camino became a majorpilgrimage route. In medieval Europe, countless pilgrims made Santiago one of Christendom’s great pilgrimage destinations, alongside Jerusalem and Rome. St. -

PDF 1.46 MB(Link Is External)

Edita Instituto da Lingua Galega Universidade de Santiago de Compostela Praza da Universidade, 4 15782 Santiago de Compostela A Coruña Correo electrónico: [email protected] Páxina web: http://ilg.usc.es/ Teléfonos +34 8818 12810 +34 8818 12802 Fax +34 81572770 Universidade de Santiago de Compostela, maio de 2011 Limiar Esta memoria recolle o labor realizado polo Instituto da Lingua Galega ao longo do ano 2010, xunto co informe de ingresos e gastos nesa anualidade. Como é preceptivo, foi presentada perante a Xunta de Goberno, que a aprobou por unanimidade en sesión celebrada na sede do ILG o día 19 de maio de 2011. Coincide esta presentación coa conmemoración do 40 aniversario do Instituto da Lingua Galega e por iso ten para todos nós unha significación especial. Naquela primavera de hai corenta anos, o día 14 de maio de 1971, anunciouse publicamente a creación do Instituto da Lingua Galega, na Universidade de Santiago de Compostela. Na semana precedente, arroupándoo, celebrárase un ciclo de conferencias sobre filoloxía galega, con importantes figuras da romanística e das filoloxías hispánica e portuguesa, e mais a presentación do método Galego 1. A acta fundacional, que contén os primeiros estatutos, é de 26 de xullo de 1971. Da mesma data é o primeiro padroado, integrado por Manuel García Garrido (Reitor), Constantino García González (Cate- drático de Filoloxía Románica, que sería nomeado Director), Manuel Díaz y Díaz (Catedrático de Filoloxía Latina, Subdirector), Ricardo Carballo Calero (representante do Centro de Estudios Fingoi, Secretario), Xosé F. Filgueira Valverde (representante do Instituto Padre Sarmiento), Marino Dónega Rozas (represen- tante da Real Academia Galega), Xerardo Fernández Albor (representante da Fundación Penzol), Xoaquín Arias Díaz de Rábago (representante da Fundación “Pedro Barrié, Conde de Fenosa”) e Ramón Otero Túñez (Decano da Facultade de Filosofía e Letras). -

I.- Programme of Activities for English Students

I.- Programme of activities for English students Day Time Activity Participating Participating students teachers Wednesday 11.10 Pick up English group from English students Carmen, Arron, 25th March am Santiago airport Luciano 6.00 pm Cathedral rooftops Carmen, Ana, English & Galician Arron 7.00pm Circuit Santiago's old town students 9.00 pm Come back to Brión and to houses Thursday 26th 8.45 am Tour of the coast English & Galician Afonso, Carmen, March (Toxosoutos waterfall, students Arron Noia, Castro de Baroña, Corrubedo, Rianxo) 7.00 pm Come back to Brión and go home Friday 27th 8:45 am Presentation English & Galician Afonso, Carmen, March students Arron 10:00am Circuit around Brión Suso, María Tilve 1:00 pm Reception with the mayor Luciano, Afonso, 2.00 pm Come back home Carmen, Arron and staff * Monday 30th 8:45 am A day at IES de Brión English students & Staff, Arron March Galician students 2.00 pm Go home Tuesday 31st 8:45 am Santiago English students Pilar March 10:00am Tour of the old town Agustín 11.30am Galicia Dixital 12.30am Circuit Santiago's old town Carmen, Arron 2.00 pm Come back to Brión and go home -1- Wednesday 1st 8:45 am Lugo English & Galician Afonso, Carmen, April students Arron Centro da interpretación da muralla Casa dos mosaicos Museo Provincial Come back to Brión and go 7.30pm home Thursday 2nd 8:45 am A Coruña English students & Lidia, Nanina, April 2nd school year Carmen, Afonso, 10.30 Tour of the old town students (only in the Arron am morning) Music Concert at Opera 12.00am Palace 3.00 pm Hércules Tower 4.30 pm Domus English & Galician students and parents.