DECLARATION This Work Has Not Previously Been Accepted In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guide to the Atlantic Provinces ' Published by Parks Canada Under Authority Ot the Hon

Parks Pares Canada Canada Atlantic Guide to the Atlantic Provinces ' Published by Parks Canada under authority ot the Hon. J. Hugh Faulkner Minister of Indian and Northern Affairs, Ottawa, 1978. QS-7055-000-EE-A1 Catalogue No. R62-101/1978 ISBN 0-662-01630-0 Illustration credits: Drawings of national historic parks and sites by C. W. Kettlewell. Photo credits: Photos by Ted Grant except photo on page 21 by J. Foley. Design: Judith Gregory, Design Partnership. Cette publication est aussi disponible en français. Cover: Cape Breton Highlands National Park Introduction Visitors to Canada's Atlantic provinces will find a warm welcome in one of the most beautiful and interesting parts of our country. This guide describes briefly each of the seven national parks, 19 national historic parks and sites and the St. Peters Canal, all of which are operated by Parks Canada for the education, benefit and enjoyment of all Canadians. The Parliament of Canada has set aside these places to be preserved for 3 all time as reminders of the great beauty of our land and the achievements of its founders. More detailed information on any of the parks or sites described in this guide may be obtained by writing to: Director Parks Canada Atlantic Region Historic Properties Upper Water Street Halifax, Nova Scotia B3J1S9 Port Royal Habitation National Historic Park National Parks and National Historic 1 St. Andrews Blockhouse 19 Fort Amherst Parks and Sites in the Atlantic 2 Carleton Martello Tower 20 Province House Provinces: 3 Fundy National Park 21 Prince Edward Island National Park 4 Fort Beausejour 22 Gros Morne National Park 5 Kouchibouguac National Park 23 Port au Choix 6 Fort Edward 24 L'Anse aux Meadows 7 Grand Pré 25 Terra Nova National Park 8 Fort Anne 26 Signal Hill 9 Port Royal 27 Cape Spear Lighthouse 10 Kejimkujik National Park 28 Castle Hill 11 Historic Properties 12 Halifax Citadel 4 13 Prince of Wales Martello Tower 14 York Redoubt 15 Fortress of Louisbourg 16 Alexander Graham Bell National Historic Park 17 St. -

Closure of Important Parks Canada Archaeological Facility The

July 19, 2017 For Immediate Release Re: Closure of Important Parks Canada Archaeological Facility The Newfoundland and Labrador Archaeological Society is saddened to learn of Parks Canada’s continuing plans to close their Archaeology Lab in Dartmouth, Nova Scotia. This purpose-built facility was just opened in 2009, specifically designed to preserve, house, and protect the archaeological artifacts from Atlantic Canada’s archaeological sites under federal jurisdiction. According to a report from the Nova Scotia Archaeological Society (NSAS), Parks Canada’s continued plans are to shutter this world-class laboratory, and ship the archaeological artifacts stored there to Gatineau, Quebec, for long-term storage. According to data released by the NSAS, the archaeological collection numbers approximately “1.45 million archaeological objects representing thousands of years of Atlantic Canadian heritage”. These include artifacts from the province of Newfoundland and Labrador, including sites at Signal Hill National Historic Site, Castle Hill National Historic Site, L’Anse aux Meadows National Historic Site, Terra Nova National Park, Gros Morne National Park, and the Torngat Mountains National Park. An archaeological collection represents more than just objects—also stored at this facility are the accompanying catalogues, site records, maps and photographs. For Immediate Release Re: Closure of Important Parks Canada Archaeological Facility This facility is used by a wide swath of heritage professionals and students. Federal and provincial heritage specialists, private heritage industry consultants, university researchers, conservators, community groups, and students of all ages have visited and made use of the centre. Indeed, the Archaeology Laboratory is more than just a state-of-the-art artifact storage facility for archaeological artifacts—its value also lies in the modern equipment housed in its laboratories, in the information held in its reference collections, site records, and book collections, and in the collective knowledge of its staff. -

Beeston, Tiverton and Tilstone Fearnall Neighbourhood Plan Includes Policies That Seek to Steer and Guide Land-Use Planning Decisions in the Area

Beeston, Tiverton and Tilstone Fearnall Neighbourhood Development Plan 2017 - 2030 December 2017 1 | Page Contents 1.1 Foreword ................................................................................................................................. 5 1.2 Acknowledgements .................................................................................................................. 5 2. BACKGROUND ................................................................................................................................ 6 2.1 Neighbourhood Plans ............................................................................................................... 6 2.2 A Neighbourhood Plan for Beeston, Tiverton and Tilstone Fearnall ........................................ 6 2.3 Planning Regulations ................................................................................................................ 8 3. BEESTON, TIVERTON AND TILSTONE FEARNALL .......................................................................... 8 3.1 A Brief History .......................................................................................................................... 8 3.2 Village Demographic .............................................................................................................. 10 3.3 The Villages’ Economy ........................................................................................................... 11 3.4 Community Facilities ............................................................................................................ -

3.6Mb PDF File

Be sure to visit all the National Parks and National Historic Sites of Canada in Nova Scotia: • Halifax Citadel National • Historic Site of Canada Prince of Wales Tower National • Historic Site of Canada York Redoubt National Historic • Site of Canada Fort McNab National Historic • Site of Canada Georges Island National • Historic Site of Canada Grand-Pré National Historic • Site of Canada Fort Edward National • Historic Site of Canada New England Planters Exhibit • • Port-Royal National Historic Kejimkujik National Park of Canada – Seaside • Site of Canada • Fort The Bank Fishery/Age of Sail Exhibit • Historic Site of Canada • Melanson SettlementAnne National Alexander Graham Bell National Historic Site National Historic Site of Canada • of Canada • Kejimkujik National Park and Marconi National Historic National Historic Site of Canada • Site of Canada Fortress of Louisbourg National Historic Site of • Canada Canso Islands National • Historic Site of Canada St. Peters Canal National • Historic Site of Canada Cape Breton Highlands National Park/Cabot T National Parks and National Historic rail Sites of Canada in Nova Scotia See inside for details on great things to see and do year-round in Nova Scotia including camping, hiking, interpretation activities and more! Proudly Bringing You Canada At Its Best Planning Your Visit to the National Parks and Land and culture are woven into the tapestry of Canada's history National Historic Sites of Canada and the Canadian spirit. The richness of our great country is To receive FREE trip-planning information on the celebrated in a network of protected places that allow us to National Parks and National Historic Sites of Canada understand the land, people and events that shaped Canada. -

It Is Now Commonplace to Think of Preservation As Part of the State's

It is now commonplace to think of preservation as part of the state’s responsibility to protect the public’s interests and welfare. But what happens when government fails to be a good steward of heritage, or worse, engages in its destruction? Activism, as a soft means of citizen oversight and influence in government, has become a central component of preservation. Victor Hugo shaped the role and the responsibilities of preservation activism through newspaper editorials such as these two calls to arms against “demolishers.” He fearlessly spoke truth to power, publishing scathing accusations of negligence and malfeasance against government bureaucrats and private developers for destroying beautiful historic buildings. The beauty of historic architecture was a public good, belonging to everyone and in need of protection. Hugo was born in Besançon, France, in 1802. His father was a military officer, and during Hugo’s childhood, years of political turmoil, his family moved frequently, including to Italy and Spain. He settled in Paris with his mother in 1812, where he developed his literary talents, publishing his first novel in 1825. Hugo’s numerous works of fiction and poetry increasingly took up social injustices, and, after being elected to the Academie Française over the objections of opponents of Romanticism, he became increasingly involved in national politics. His novel Notre-Dame de Paris (The Hunchback of Notre Dame, 1831) helped inspire the restoration of Paris’s cathedral, and a renewed appreciation of Paris’s pre-Renaissance physiognomy. It was published a year after the establishment of the Comité des Arts, later transformed into the Commission de Monuments Historiques with Ludovic Vitet (1802-73) as Inspector General. -

ACTION STATIONS! Volume 37 - Issue 1 Winter 2018

HMCS SACKVILLE - CANADA’S NAVAL MEMORIAL ACTION STATIONS! Volume 37 - Issue 1 Winter 2018 Action Stations Winter 2018 1 Volume 37 - Issue 1 ACTION STATIONS! Winter 2018 Editor and design: Our Cover LCdr ret’d Pat Jessup, RCN Chair - Commemorations, CNMT [email protected] Editorial Committee LS ret’d Steve Rowland, RCN Cdr ret’d Len Canfield, RCN - Public Affairs LCdr ret’d Doug Thomas, RCN - Exec. Director Debbie Findlay - Financial Officer Editorial Associates Major ret’d Peter Holmes, RCAF Tanya Cowbrough Carl Anderson CPO Dean Boettger, RCN webmaster: Steve Rowland Permanently moored in the Thames close to London Bridge, HMS Belfast was commissioned into the Royal Photographers Navy in August 1939. In late 1942 she was assigned for duty in the North Atlantic where she played a key role Lt(N) ret’d Ian Urquhart, RCN in the battle of North Cape, which ended in the sinking Cdr ret’d Bill Gard, RCN of the German battle cruiser Scharnhorst. In June 1944 Doug Struthers HMS Belfast led the naval bombardment off Normandy in Cdr ret’d Heather Armstrong, RCN support of the Allied landings of D-Day. She last fired her guns in anger during the Korean War, when she earned the name “that straight-shooting ship”. HMS Belfast is Garry Weir now part of the Imperial War Museum and along with http://www.forposterityssake.ca/ HMCS Sackville, a member of the Historical Naval Ships Association. HMS Belfast turns 80 in 2018 and is open Roger Litwiller: daily to visitors. http://www.rogerlitwiller.com/ HMS Belfast photograph courtesy of the Imperial -

A Magical Christmastime

Terms & Conditions Booking and payment terms Christmas Parties: £10.00 per person deposit required to secure your booking. Full payment required 6 weeks prior to the event. All payments are non refundable and non transferable. Festive Luncheons, Christmas Day and Boxing Day: £10.00 per person deposit required to secure your booking. Full payment 6 weeks prior to the event. £50 per room deposit will be required to secure all bedroom bookings, the remaining balance to be paid on departure. Credit card numbers will be required to secure all bedroom bookings. Preorders will be required for all meals. Peckforton Castle, Stonehouse Lane, Peckforton,Tarporley, Cheshire CW6 9TN A Magical Christmas Main Reception: 01829 260 930 Fax: 01829 261 230 Email: [email protected] www.peckfortoncastle.co.uk CHRISTMAS & NEW YEAR 2012Time HOW TO FIND US By Air Manchester or Liverpool Airport – both 40 minute drive. By Train Nearest stations are Crewe and Chester Christmas Booking Form – both 20 minute drive. By Road from M56 From M56 come off at Junction 10 following signs Name .................................................................................................................................................... to Whitchurch A49, follow this road for approx Address ............................................................................................................................................... A Magical Christmas 25 minutes; you will eventually come to traffic lights with the Red Fox Pub on your right hand ................................................................................................................................................................. -

Cultural Assets of Nova Scotia African Nova Scotian Tourism Guide 2 Come Visit the Birthplace of Canada’S Black Community

Cultural Assets of NovA scotiA African Nova scotian tourism Guide 2 Come visit the birthplace of Canada’s Black community. Situated on the east coast of this beautiful country, Nova Scotia is home to approximately 20,000 residents of African descent. Our presence in this province traces back to the 1600s, and we were recorded as being present in the provincial capital during its founding in 1749. Come walk the lands that were settled by African Americans who came to the Maritimes—as enslaved labour for the New England Planters in the 1760s, Black Loyalists between 1782 and 1784, Jamaican Maroons who were exiled from their home lands in 1796, Black refugees of the War of 1812, and Caribbean immigrants to Cape Breton in the 1890s. The descendants of these groups are recognized as the indigenous African Nova Scotian population. We came to this land as enslaved and free persons: labourers, sailors, farmers, merchants, skilled craftspersons, weavers, coopers, basket-makers, and more. We brought with us the remnants of our cultural identities as we put down roots in our new home and over time, we forged the two together and created our own unique cultural identity. Today, some 300 years later, there are festivals and gatherings throughout the year that acknowledge and celebrate the vibrant, rich African Nova Scotian culture. We will always be here, remembering and honouring the past, living in the present, and looking towards the future. 1 table of contents Halifax Metro region 6 SoutH SHore and YarMoutH & acadian SHoreS regionS 20 BaY of fundY & annapoliS ValleY region 29 nortHuMBerland SHore region 40 eaStern SHore region 46 cape Breton iSland region 50 See page 64 for detailed map. -

Journal No 28 Spring 2017

The Regimental Association of The Queen’s Own Buffs (PWRR) The Royal Kent Regiment THE JOURNAL Number 28 Spring 2017 CONTENTS STUMP ROAD CEMETERY ............................................ 1 PRESIDENT’S JOTTINGS .............................................. 2 EDItor’S PAGE ............................................................. 3 BRANCH NEWS .............................................................. 4-9 THE 62 CLUB .................................................................. 10 ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING ....................................... 11-13 BENEATH BELL HARRY ................................................. 14-15 ANYONE FOR CRICKET ................................................ 15-16 CANTERBURY REUNION ADMIN ORDER 2017 ........... 17-20 MAIdstoNE REUNION ADMIN ORDER 2017 .............. 20-21 THE SEA WOLVES, OPERATION POSTMASTER OPERATION CREEK & JAMES BOND 007 ................... 22-26 LT COL WILLIAM ROBERT DAWSON (THE BOY COLONEL) .................................................... 26-29 MAJOR-GENERAL EDWARD CHARLES INGOUVILLE WILLIAMS, C.B., D.S.O. (INKY BILL) ....... 30-31 THE BUFFS’ LINKS WITH THE TOWER AND THE CITY OF LONDON ......................................... 32 ASSOCIATION TRIP TO THE SOMME........................... 33-35 CANterbury REUNION 2016 ..................................... 36-38 MAIdstoNE REUNION 2016 ........................................ 39-41 TOWER OF LONDON PARADE 2016 ............................ 42-43 TURNING THE PAGE ..................................................... 44-45 -

LAWRENCE ALLOWAY Pedagogy, Practice, and the Recognition of Audience, 1948-1959

LAWRENCE ALLOWAY Pedagogy, Practice, and the Recognition of Audience, 1948-1959 In the annals of art history, and within canonical accounts of the Independent Group (IG), Lawrence Alloway's importance as a writer and art critic is generally attributed to two achievements: his role in identifying the emergence of pop art and his conceptualization of and advocacy for cultural pluralism under the banner of a "popular-art-fine-art continuum:' While the phrase "cultural continuum" first appeared in print in 1955 in an article by Alloway's close friend and collaborator the artist John McHale, Alloway himself had introduced it the year before during a lecture called "The Human Image" in one of the IG's sessions titled ''.Aesthetic Problems of Contemporary Art:' 1 Using Francis Bacon's synthesis of imagery from both fine art and pop art (by which Alloway meant popular culture) sources as evidence that a "fine art-popular art continuum now eXists;' Alloway continued to develop and refine his thinking about the nature and condition of this continuum in three subsequent teXts: "The Arts and the Mass Media" (1958), "The Long Front of Culture" (1959), and "Notes on Abstract Art and the Mass Media" (1960). In 1957, in a professionally early and strikingly confident account of his own aesthetic interests and motivations, Alloway highlighted two particular factors that led to the overlapping of his "consumption of popular art (industrialized, mass produced)" with his "consumption of fine art (unique, luXurious):' 3 First, for people of his generation who grew up interested in the visual arts, popular forms of mass media (newspapers, magazines, cinema, television) were part of everyday living rather than something eXceptional. -

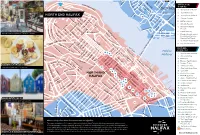

NORTH END HALIFAX T R T S T C

W In e d v t ia i m St A n S a s d e h 322 n a t e m o w W r S iv H e G i v y d 111 N l N l A s R ort e ATTRACTIONS h M R d R d a o o R n F rg d o se d a & VENUES in w d l K al D a o enc R lm H r l B DARTMOUTH rest d E e e A. The Hydrostone Market e d Ave e S st b v Bedford R Gle t er n e o B. The Halifax Forum l S A l L t s Green Rd i y e v nc v e h i t t Basin c S o e i NORTH END HALIFAX t r t S t C. The Little Dutch Church r L m k f Acadia St y G S S c nc 7 a t A N h J t u n S t o t S a n D. Creative Crossing va S t z n a l St Pauls y A l o e r lb e s NW a t P w t E. Halifax Common D s e a S y r e t rt r s R St V S S D e e o r r t J n F. Africville Museum b o a k R i t D t L rv l d e S y c a i u S s d e n s a G. -

Magnolia Building Landmark Nomination Form

• attachment 2 -a — // — S — — • _ / - — —~— / — — • — — —. / ,• ~ —=——~ — — ~ ~ LX /.ii — - ~ ~ LZ q. - — —— — _r — — — —- / -‘—i ~\ •~ ~ ~ II p / ~ ,tii - -, ~ - — — • ~— i/i t 1—n F ~: ?~‘ 4~iii•ri’ ~ •‘ /~ I /;~ IL •~ ~‘/I ‘MW... ~ flu 1/:1 T ~ I 2~ ~ f-. -:~ ~::~-~7; 1. -1 •1/.. ~- Th gnolia .11 ding A Living Dallas Heritage a landmark designation report y the Dallas Landmark Preservation Committee ay.1978 THE MAGNOLIA BUILDING -~Pr LIVI-NG- DALLAS HERITAGE I. INTRODUCTION: This report has been prepared by the Historic Landmark Preservation Comittee of the Planning Con~nission and by the Department of Urban Planning. It is a study of the Magnolia Building, renamed the Mobil Building, to determine its significance as a historic landmark and to consider the question of whether it should be protected. The study will also consider what features should be Drotected and what approaches are ap propriate if the building is determined to be worthy of such protection. Designation under the City’s landmark program, together with preservation criteria, would be a major tool for preserving any building deemed to be historically significant as a living part of Dallas’ heritage. If such a building is unoccupied or underutilized, an appropriate reuse would be es sential for its continued viability. Hopefully, a new use could be found for a historic landmark building which would not only preserve the building as economically viable, but which would provide some access and amenity to the public appropriate to its significance as a focus of community sentiment. The Magnolia Building has for years been one of Dallas’ most significant buildings. Its architectural distinction, its association with the city’s economic life, and its extraordinary visual domination of the downtown sky line, topped by the Flying Red Horse, all reinforce its overall impact.