Phoenicia During the Iron Age II Period

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Satrap of Western Anatolia and the Greeks

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2017 The aS trap Of Western Anatolia And The Greeks Eyal Meyer University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity Commons Recommended Citation Meyer, Eyal, "The aS trap Of Western Anatolia And The Greeks" (2017). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 2473. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2473 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2473 For more information, please contact [email protected]. The aS trap Of Western Anatolia And The Greeks Abstract This dissertation explores the extent to which Persian policies in the western satrapies originated from the provincial capitals in the Anatolian periphery rather than from the royal centers in the Persian heartland in the fifth ec ntury BC. I begin by establishing that the Persian administrative apparatus was a product of a grand reform initiated by Darius I, which was aimed at producing a more uniform and centralized administrative infrastructure. In the following chapter I show that the provincial administration was embedded with chancellors, scribes, secretaries and military personnel of royal status and that the satrapies were periodically inspected by the Persian King or his loyal agents, which allowed to central authorities to monitory the provinces. In chapter three I delineate the extent of satrapal authority, responsibility and resources, and conclude that the satraps were supplied with considerable resources which enabled to fulfill the duties of their office. After the power dynamic between the Great Persian King and his provincial governors and the nature of the office of satrap has been analyzed, I begin a diachronic scrutiny of Greco-Persian interactions in the fifth century BC. -

A Christian's Map of the Holy Land

A CHRISTIAN'S MAP OF THE HOLY LAND Sidon N ia ic n e o Zarefath h P (Sarepta) n R E i I T U A y r t s i Mt. of Lebanon n i Mt. of Antilebanon Mt. M y Hermon ’ Beaufort n s a u b s s LEGEND e J A IJON a H Kal'at S Towns visited by Jesus as I L e o n Nain t e s Nimrud mentioned in the Gospels Caesarea I C Philippi (Banias, Paneas) Old Towns New Towns ABEL BETH DAN I MA’ACHA T Tyre A B a n Ruins Fortress/Castle I N i a s Lake Je KANAH Journeys of Jesus E s Pjlaia E u N s ’ Ancient Road HADDERY TYRE M O i REHOB n S (ROSH HANIKRA) A i KUNEITRA s Bar'am t r H y s u Towns visited by Jesus MISREPOTH in K Kedesh sc MAIM Ph a Sidon P oe Merom am n HAZOR D Tyre ic o U N ACHZIV ia BET HANOTH t Caesarea Philippi d a o Bethsaida Julias GISCALA HAROSH A R Capernaum an A om Tabgha E R G Magdala Shave ACHSAPH E SAFED Zion n Cana E L a Nazareth I RAMAH d r Nain L Chorazin o J Bethsaida Bethabara N Mt. of Beatitudes A Julias Shechem (Jacob’s Well) ACRE GOLAN Bethany (Mt. of Olives) PISE GENES VENISE AMALFI (Akko) G Capernaum A CABUL Bethany (Jordan) Tabgha Ephraim Jotapata (Heptapegon) Gergesa (Kursi) Jericho R 70 A.D. Magdala Jerusalem HAIFA 1187 Emmaus HIPPOS (Susita) Horns of Hittin Bethlehem K TIBERIAS R i Arbel APHEK s Gamala h Sea of o Atlit n TARICHAFA Galilee SEPPHORIS Castle pelerin Y a r m u k E Bet Tsippori Cana Shearim Yezreel Valley Mt. -

Three Conquests of Canaan

ÅA Wars in the Middle East are almost an every day part of Eero Junkkaala:of Three Canaan Conquests our lives, and undeniably the history of war in this area is very long indeed. This study examines three such wars, all of which were directed against the Land of Canaan. Two campaigns were conducted by Egyptian Pharaohs and one by the Israelites. The question considered being Eero Junkkaala whether or not these wars really took place. This study gives one methodological viewpoint to answer this ques- tion. The author studies the archaeology of all the geo- Three Conquests of Canaan graphical sites mentioned in the lists of Thutmosis III and A Comparative Study of Two Egyptian Military Campaigns and Shishak and compares them with the cities mentioned in Joshua 10-12 in the Light of Recent Archaeological Evidence the Conquest stories in the Book of Joshua. Altogether 116 sites were studied, and the com- parison between the texts and the archaeological results offered a possibility of establishing whether the cities mentioned, in the sources in question, were inhabited, and, furthermore, might have been destroyed during the time of the Pharaohs and the biblical settlement pe- riod. Despite the nature of the two written sources being so very different it was possible to make a comparative study. This study gives a fresh view on the fierce discus- sion concerning the emergence of the Israelites. It also challenges both Egyptological and biblical studies to use the written texts and the archaeological material togeth- er so that they are not so separated from each other, as is often the case. -

And KEEPING up with the PERSIANS Some Reflections on Cultural Links in the Persian Empire

Working draft, not for distribution without permission of the author 1 ‘MANNERS MAKYTH MAN’ and KEEPING UP WITH THE PERSIANS Some reflections on cultural links in the Persian Empire Christopher Tuplin (University of Liverpool) Revised version: 9 June 2008 The purpose of the meeting (according to the web site) is to explore how ancient peoples expressed their identities by establishing, constructing, or inventing links with other societies that crossed traditional ethnic and geographic lines. These cross-cultural links complicates, undermine, or give nuance to conventional dichotomies such as self/other, Greek/barbarian, and Jew/gentile In the Achaemenid imperial context this offers a fairly wide remit. But it is a remit limited – or distorted – by the evidence. For in this, as in all aspects of Achaemenid history, we face a set of sources that spreads unevenly across the temporal, spatial and analytical space of the empire. For what might count as an unmediated means of access to a specifically Persian viewpoint we are pretty much confined to iconographically decorated monuments and associated royal inscriptions at Behistun, Persepolis and Susa (which are at least, on the face of it, intended to broach ideological topics) and the Persepolis Fortification and Treasury archives (which emphatically are not). This material is not formally or (to a large extent) chronologically commensurate with the voluminous, but unevenly distributed, Greek discourse that provides so much of the narrative of Achaemenid imperial history. Some of it may appear more commensurate with the substantial body of iconographically decorated monuments (most not associated with inscriptions) derived from western Anatolia that provides much of the material in the two papers under discussion. -

Quantitative Dynamics of Human Empires

Quantitative Dynamics of Human Empires Cesare Marchetti and Jesse H. Ausubel FOREWORD Humans are territorial animals, and most wars are squabbles over territory. become global. And, incidentally, once a month they have their top managers A basic territorial instinct is imprinted in the limbic brain—or our “snake meet somewhere to refresh the hierarchy, although the formal motives are brain” as it is sometimes dubbed. This basic instinct is central to our daily life. to coordinate business and exchange experiences. The political machinery is Only external constraints can limit the greedy desire to bring more territory more viscous, and we may have to wait a couple more generations to see a under control. With the encouragement of Andrew Marshall, we thought it global empire. might be instructive to dig into the mechanisms of territoriality and their role The fact that the growth of an empire follows a single logistic equation in human history and the future. for hundreds of years suggests that the whole process is under the control In this report, we analyze twenty extreme examples of territoriality, of automatic mechanisms, much more than the whims of Genghis Khan namely empires. The empires grow logistically with time constants of tens to or Napoleon. The intuitions of Menenius Agrippa in ancient Rome and of hundreds of years, following a single equation. We discovered that the size of Thomas Hobbes in his Leviathan may, after all, be scientifically true. empires corresponds to a couple of weeks of travel from the capital to the rim We are grateful to Prof. Brunetto Chiarelli for encouraging publication using the fastest transportation system available. -

Early Iron Age Phoenician Networks: an Optical Mineralogy Study of Phoenician Bichrome and Related Wares in Cyprus*

doi: 10.2143/AWE.14.0.3108189 AWE 14 (2015) 73-110 EARLY IRON AGE PHOENICIAN NETWORKS: AN OPTICAL MINERALOGY STUDY OF PHOENICIAN BICHROME AND RELATED WARES IN CYPRUS* AYELET GILBOA and YUVAL GOREN Abstract Ancient Phoenicia was fragmented into several, oft-times competing polities. However, the possibility of defining archaeologically the exchange networks of each Phoenician city remains rather unexplored. This paper presents such an attempt, regarding the Early Iron Age (late 12th‒9th centuries BC). It is based on an Optical Mineralogy study of about 50 Phoenician ceramic containers in Cyprus, especially those of the ‘Phoenician Bichrome’ group. The latter are commonly employed as a major proxy for tracing the earliest Phoeni- cian mercantile ventures in the Iron Age. This is the first systematic provenance analysis of these wares and the first attempt to pinpoint the regions/polities in Phoenicia which partook in this export to Cyprus. The results are interpreted in a wider context of Cypro-Phoenician interrelationships during this period. INTRODUCTION The collapse of most Late Bronze Age (LBA) socio-political entities around the eastern and central Mediterranean (ca. 1250–1150 BC) is marked, inter alia, by the failure of major interregional commercial mechanisms. Previous views, however, that the LBA/Iron Age transition exemplifies a complete cessation of Mediterranean interaction, have continuously been modified and in recent years ever-growing numbers of scholars argue for a considerable measure of continuity in this respect.1 Indeed, cross-Mediterranean traffic and flow of goods did not come to a stand- still in the Early Iron Age. Exchange networks linking regions as far as the eastern Mediterranean and the Atlantic coast of Iberia are attested mainly by metal artefacts, the metals themselves, and by various ‘luxuries’, such as jewellery, faience objects * We thank wholeheartedly Dr Pavlos Flourentzos and Dr Maria Hadjicosti, former directors of the Department of Antiquities of Cyprus, for granting us permission to carry out this research. -

Study Guide #16 the Rise of Macedonia and Alexander the Great

Name_____________________________ Global Studies Study Guide #16 The Rise of Macedonia and Alexander the Great The Rise of Macedonia. Macedonia was strategically located on a trade route between Greece and Asia. The Macedonians suffered near constant raids from their neighbors and became skilled in horseback riding and cavalry fighting. Although the Greeks considered the Macedonians to be semibarbaric because they lived in villages instead of cities, Greek culture had a strong influence in Macedonia, particularly after a new Macedonian king, Philip II, took the throne in 359 B.C. As a child, Philip II had been a hostage in the Greek city of Thebes. While there, he studied Greek military strategies and learned the uses of the Greek infantry formation, the phalanx. After he left Thebes and became king of Macedonia, Philip used his knowledge to set up a professional army consisting of cavalry, the phalanx, and archers, making the Macedonian army one of the strongest in the world at that time. Philip’s ambitions led him to conquer Thrace, to the east of Macedonia. Then he moved to the trade routes between the Aegean Sea and the Black Sea. Soon Philip turned his attention to the Greek citystates. Although some Greek leaders tried to get the city-states to unite, they were unable to forge a common defense, which made them vulnerable to the Macedonian threat. Eventually, Philip conquered all the city-states, including Athens and Thebes, which he defeated at the battle of Chaeronea in 338 B.C. This battle finally ended the independence of the Greek city-states. -

Early Jaffa: from the Bronze Age to the Persian Period

C HA pt ER 6 EARLY JAFFA: FROM THE BRONZE AGE TO THE PERSIAN PERIOD A ARON A . B URKE University of California, Los Angeles lthough Jaffa is repeatedly identified featured a natural, deepwater anchorage along its rocky as one of the most important ports of the western side. A natural breakwater is formed by a ridge, Asouthern Levantine coast during the Bronze located about 200 m from the western edge of the Bronze and Iron Ages, limited publication of its archaeological Age settlement, that can still be seen today.2 remains and equally limited consideration of its his- Although a geomorphological study has yet to be torical role have meant that a review of its historical undertaken, a number of factors indicate that an estuary significance is still necessary. Careful consideration of existed to the east of the site and functioned as the early Jaffa’s geographic location, its role during the Bronze harbor of Jaffa (see Hanauer 1903a, 1903b).3 The data and Iron Ages, and its continued importance until the for this include: (1) a depression that collected water early twentieth century C.E. reveal that its emergence to the south of the American (later German) colony as an important settlement and port was no accident. known as the Baasah (Clermont-Ganneau 1874:103; This essay reviews, therefore, the evidence for Jaffa’s see also Hanauer 1903b:258–260) (see also Figure 13.1 foundation and subsequent role from the Early Bronze and Figure 13.2); (2) a wall identified as a seawall that Age through the coming of Alexander at the end of the was encountered at some depth within this depression Persian period. -

Members' Magazine

oi.uchicago.edu News & Notes MEMBERS’ MAGAZINE ISSUE 241 | SPRING 2019 | TRAVEL oi.uchicago.edu THE ORIENTAL INSTITUTE 1155 East 58th Street Chicago, IL, 60637 WEBSITE oi.uchicago.edu FACSIMILE 773.702.9853 MEMBERSHIP INFORMATION 773.702.9513 [email protected] MUSEUM INFORMATION 773.702.9520 SUQ GIFT AND BOOK SHOP 773.702.9510 ADMINISTRATIVE OFFICE 773.702.9514 [email protected] MUSEUM GALLERY HOURS Mon: Closed Sun–Tue, Thu–Sat: 10am–5pm Wed: 10am–8pm CREDITS Editors: Matt Welton, Charissa Johnson, Rebecca Cain, Steve Townshend, & Tasha Vorderstrasse Designers: Rebecca Cain, Matt Welton, & Charissa Johnson Additional photos: Judith R. Kolar, Sara Jean Lindholm, & George Surgeon News & Notes is a quarterly publication of the Oriental Institute, printed exclusively as one of the privileges of membership. ON THE COVER: View of the Nile from the Old Cataract Hotel, Aswan Egypt. BACKGROUND: Castelli drawing of a wondrous pear in human form. Biblioteca Communale di Palermo, Ms.3 Qq E 94, fol. 36r. oi.uchicago.edu From the DIRECTOR’S STUDY REMEMBERING MIGUEL CIVIL (1926–2019) Miguel Civil’s scholarly contributions are simply monumental—more than any other scholar, he shaped the modern, post-WWII, study of Sumerology. Our understanding of Sumerian writing, lexicography, grammar, literature, agriculture, and socio-economic institutions all bear his deep imprint. He was a mentor, teacher, and friend to two generations of Sumerologists, Assyriologists, and archaeologists. It remains the greatest honor of my career to have come to Chicago to replace Miguel after he retired in 2001. Born outside of Barcelona in 1926 and trained in Paris, Miguel came to the US in 1958 to take the position of associate researcher under Samuel Noah Kramer at the Uni- versity of Pennsylvania. -

Avarishyksos-Marcus2

Th e Enigma of the Hyksos Volume I BBietak,ietak, CCAENLAENL 99.indd.indd 1 110.10.20190.10.2019 110:27:030:27:03 Contributions to the Archaeology of Egypt, Nubia and the Levant CAENL Edited by Manfred Bietak Volume 9 2019 Harrassowitz Verlag · Wiesbaden BBietak,ietak, CCAENLAENL 99.indd.indd 2 110.10.20190.10.2019 110:27:090:27:09 Th e Enigma of the Hyksos Volume I ASOR Conference Boston 2017 − ICAANE Conference Munich 2018 – Collected Papers Edited by Manfred Bietak and Silvia Prell 2019 Harrassowitz Verlag · Wiesbaden BBietak,ietak, CCAENLAENL 99.indd.indd 3 110.10.20190.10.2019 110:27:090:27:09 Cover illustration: redrawn by S. Prell after J. de Morgan, Fouilles à Dahchour: mars - juin 1894, Vienna 1895, fi gs. 137-140 Th is project has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (grant agreement No 668640). Th is publication has undergone the process of international peer review. Open Access: Wo nicht anders festgehalten, ist diese Publikation lizenziert unter der Creative Commons Lizenz Namensnennung 4.0 Open access: Except where otherwise noted, this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Bibliografi sche Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografi e; detaillierte bibliografi sche Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.dnb.de abrufbar. Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek Th e Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografi e; detailed bibliographic data are available in the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de For further information about our publishing program consult our website http://www.harrassowitz-verlag.de © Otto Harrassowitz GmbH & Co. -

The Cypriot Kingdoms in the Archaic Age: a Multicultural Experience in the Eastern Mediterranean Anna Cannavò

The Cypriot Kingdoms in the Archaic Age: a Multicultural Experience in the Eastern Mediterranean Anna Cannavò To cite this version: Anna Cannavò. The Cypriot Kingdoms in the Archaic Age: a Multicultural Experience in the Eastern Mediterranean. Roma 2008 - XVII International Congress of Classical Ar- chaeology: Meetings Between cultures in the Eastern Mediterranean, 2008, Roma, Italy. http://151.12.58.75/archeologia/bao_document/articoli/5_CANNAVO.pdf. hal-00946152 HAL Id: hal-00946152 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00946152 Submitted on 13 Feb 2014 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Anna Cannavò The Cypriot Kingdoms in the Archaic Age: A Multicultural Experience in the Eastern Mediterranean Publishing in 1984 his masterwork about kingship in Greece before the Hellenistic age Pierre Carlier wrote 1 in his introduction: “Le cas des royautés chypriotes est très différent [ i.e. par rapport à celui des royautés grecques antérieures à la conquête d'Alexandre]: leur étude systématique n'a jamais été tentée à ma connaissance. La plupart des documents épigraphiques en écriture syllabique ont été réunis et analysés par O. Masson[ 2] et les testimonia relatifs à Salamine ont été rassemblés par M. -

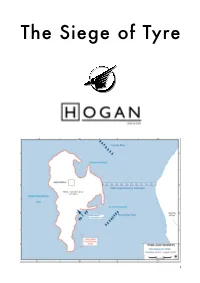

The Siege of Tyre

The Siege of Tyre 1 Contents Past Questions! 2 Arrian’s Account Of The Siege! 4 Key Points! 14 Past Questions 1985 Give Alexander's reasons for besieging Tyre and describe the siege. What does the siege tell us about Alexander's character? (50) 1991 "Alexander had no difficulty in persuading his officers that the attempt on Tyre must be made". (Arrian, Book 2. Ch. 18) What arguments did Alexander use to persuade his officers? What factors made the siege of Tyre “a tremendous undertaking"? (50) 1995 2 What particular skills did Alexander show in his sieges of Halicarnassus and Tyre? (50) 2004 (ii) The siege and capture of Tyre has been described as Perhaps the hardest task that Alexander’s military genius ever encountered. (Bury and Meiggs) (a) What were the main challenges presented by Tyre and its defenders, and how did Alexander’s genius overcome those challenges? (40) (b) What is your opinion of Alexander’s treatment of the survivors after the capture of Tyre? (10) 2012 (ii) (a) Explain why the city of Tyre was so difficult to capture. (15) (b) How did Alexander overcome the difficulties presented by Tyre and its defenders? (25) (c) What do you learn about Alexander’s character from Arrian’s account of the siege and capture of Tyre? (10) 3 Arrian’s Account Of The Siege • Alexander easily persuaded his men to make an attack on Tyre. An omen helped to convince him, because that very night during a dream he seemed to be approaching the walls of Tyre, and Heracles was stretching out his right hand towards him and leading him to the city.