A Strange Case of Angry Video Game Nerds: Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde on the Nintendo Entertainment System

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Strange Loop

A Strange Loop / Who we are Our vision We believe in theater as the most human and immediate medium to tell the stories of our time, and affirm the primacy and centrality of the playwright to the form. Our writers We support each playwright’s full creative development and nurture their unique voice, resulting in a heterogeneous mix of as many styles as there are artists. Our productions We share the stories of today by the writers of tomorrow. These intrepid, diverse artists develop plays and musicals that are relevant, intelligent, and boundary-pushing. Our plays reflect the world around us through stories that can only be told on stage. Our audience Much like our work, the 60,000 people who join us each year are curious and adventurous. Playwrights is committed to engaging and developing audiences to sustain the future of American theater. That’s why we offer affordably priced tickets to every performance to young people and others, and provide engaging content — both onsite and online — to delight and inspire new play lovers in NYC, around the country, and throughout the world. Our process We meet the individual needs of each writer in order to develop their work further. Our New Works Lab produces readings and workshops to cultivate our artists’ new projects. Through our robust commissioning program and open script submission policy, we identify and cultivate the most exciting American talent and help bring their unique vision to life. Our downtown programs …reflect and deepen our mission in numerous ways, including the innovative curriculum at our Theater School, mutually beneficial collaborations with our Resident Companies, and welcoming myriad arts and education not-for-profits that operate their programs in our studios. -

Doctor Strange Comics As Post-Fantasy

Evolving a Genre: Doctor Strange Comics as Post-Fantasy Jessie L. Rogers Thesis submitted to the faculty of the Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in English Karen Swenson, Chair Nancy A. Metz Katrina M. Powell April 15, 2019 Blacksburg, Virginia Keywords: Fantasy, Comics Studies, Postmodernism, Post-Fantasy Copyright 2019, Jessie L. Rogers Evolving a Genre: Doctor Strange Comics as Post-Fantasy Jessie L. Rogers (ABSTRACT) This thesis demonstrates that Doctor Strange comics incorporate established tropes of the fantastic canon while also incorporating postmodern techniques that modernize the genre. Strange’s debut series, Strange Tales, begins this development of stylistic changes, but it still relies heavily on standard uses of the fantastic. The 2015 series, Doctor Strange, builds on the evolution of the fantastic apparent in its predecessor while evidencing an even stronger presence of the postmodern. Such use of postmodern strategies disrupts the suspension of disbelief on which popular fantasy often relies. To show this disruption and its effects, this thesis examines Strange Tales and Doctor Strange (2015) as they relate to the fantastic cornerstones of Tolkien’s The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings and Rowling’s Harry Potter series. It begins by defining the genre of fantasy and the tenets of postmodernism, then it combines these definitions to explain the new genre of postmodern fantasy, or post-fantasy, which Doctor Strange comics develop. To show how these comics evolve the fantasy genre through applications of postmodernism, this thesis examines their use of otherworldliness and supernaturalism, as well as their characterization and narrative strategies, examining how these facets subvert our expectations of fantasy texts. -

Gaming in Libraries by Matthew Cole Introduction

Play your way to the top: Gaming in libraries By Matthew Cole Introduction Video games have come a long way since who have rarely or never played a video Atari’s suite of arcade games was released game to people who have either played on a home console. Children of the first video games for a significant portion of their video game wave have become adults lives, or had many friends who did. These themselves, and according to some counts, new researchers are uncovering deeper this population of first-wave gamers levels of impact and influence than their accounts for approximately 56 million predecessors because people who engage in members of the North American workforce an activity understand it better than those (Beck & Wade, 2004). This is important for who do not. various reasons. First, it shows that people It is important to recognize that video games who play video games are not destined to be facilitate learning rather than. General anti-social, brain-dead, basement hermits; in perception of video gaming ranges between fact, they will enter the workforce proving to those who classify it as solely recreational be as successful and resourceful as their and those who recognize the educational non-gaming counterparts. Secondly, it potential of video games. Both ends of this shows that people who play video games as spectrum touch on core principles of public children and teenagers continue to do so as libraries information and entertainment. adults. Finally, it means that the type of Therefore, this article will look at how video people who are currently researching the games can fit into the mandate and societal effects of gaming have changed from those expectations of a public library. -

The Characters and Conflicts in Marvel Studios “Doctor Strange” Movie

DOI: 10.24843/JH.2018.v22.i03.p30 ISSN: 2302-920X Jurnal Humanis, Fakultas Ilmu Budaya Unud Vol 22.3 Agustus 2018: 771-780 The Characters and Conflicts in Marvel Studios “Doctor Strange” Movie Ni Putu Ayu Mitha Hapsari1*, I Nyoman Tri Ediwan2, Ni Luh Nyoman Seri Malini3 [123]English Department - Faculty of Arts - Udayana University 1[[email protected]] 2[[email protected]] 3[[email protected]] *Corresponding Author Abstract The title of this paper is The Characters and Conflicts in Marvel Studios “Doctor Strange” Movie. This study focuses on categorization and function of the characters in the movie and conflicts in the main character (external and internal conflicts). The data of this study were taken from a movie entitled Doctor Strange. The data were collected through documentation method. In analyzing the data, the study used qualitative method. The categorization and function were analyzed based on the theory proposed by Wellek and Warren (1955:227), supported by the theory of literature proposed by Kathleen Morner (1991:31). The conflict was analyzed based on the theory of literature proposed by Kenney (1966:5). The findings show that the categorization and function of the characters in the movie are as follows: Stephen Strange (dynamic protagonist character), Kaecilius (static antagonist character). Secondary characters are The Ancient One (static protagonist character), Mordo (static protagonist character) and Christine (dynamic protagonist character). The supporting character is Wong (static protagonist character). Then there are two types of conflicts found in this movie, internal and external conflicts. Keywords: Character, Conflict, Doctor Strange. Abstrak Judul penelitian ini adalah The Characters and Conflicts in Marvel Studios “Doctor Strange” Movie. -

Program Guide Index Sgc Program Guide 2013

EVENT’S SCHEDULE Version 0.3 Updated 17.06.13 GUEST LIST MARKET PLACE SGC GROUND MAP AND MUCH MORE!!! JUNE 21ST - 23RD, 2013 HYATT REGENCY DALLAS SGCONVENTION.COM PROGRAM GUIDE INDEX SGC PROGRAM GUIDE 2013 PROGRAM’S CONTENT A quick look at the most amazing three day gaming party in the entire Southwest! This index is where you can find all the information you’re looking for with ease. SGC Woo! The Guest List What is SGC? PAGE PAGE Need more information Welcome to the convention! about your favorite 04 09 celebrities? The Schedule The Hotel PAGE PAGE For when you want to Where is SGC held, rooms be at the right place, and reservations. 05 14 at the right time. PAGE PAGE The SGC Map Where to Eat? It’s dangerous to go along. Hungry? 06 17 TAKE THIS! TABLE TOP ROOM Transport PAGE PAGE Get you card, board, dice, Arriving in Dallas and need and role-playing games directions? 08 18 ready! 2 INDEX SGC PROGRAM GUIDE 2013 PROGRAM’S CONTENT Dealer Room Want exclusive merchandise PAGE or even a rare game? We have you covered! 19 IRON MAN PAGE OF GAMING The only competition to test 24 a gamer’s skills across all consoles, genres, and eras. ARCADE ROOM Play with your fellow gamers PAGE by matching up on either retro, modern, or arcade classics! 20 COSPLAY CONTEST PAGE Of course we love cosplay at SGC! See the rules for this year’s 28 contest at SGC! MOVIE ROOM Love movies? Check out which PAGE movies we will be showing day and night! 22 THANK YOU! PAGE Thanking those who supported SGC on the 2012 Kickstarter. -

Being Jesus Christ in a Strange Land” Sermon Preached by Jeff Huber June 13-14, 2020

Theme: Church Status – It’s Complicated “Being Jesus Christ in a Strange Land” Sermon preached by Jeff Huber June 13-14, 2020 Scripture: Genesis 12:1-3; Luke 4: 28-30; Matthew 5: 13-16 VIDEO Sermon Starter SLIDE Being Jesus Christ in a Strange Land Today we begin a new series of sermons on what it means to be the church in this time of upheaval. As we were thinking about this idea and how important it is for us to talk about our mission and vision during uncertain times, the image of church status came to us because many of us often post an emoji to describe our status but if we were to do that today for the church, it would be complicated. We are still the church even though our building is closed and we are called to still find a way to be the presence of Jesus Christ, but sometimes that is disappointing and discouraging and sometimes there are new things we have discovered which bless us. We thought this graphic captures this idea which is why you sought in the opening video. GRAPHIC Its Complicated with Emojis I want to invite you, if you haven’t done so, to get out a pen or pencil and something to write on because I hope there will be some things you here today that you want to take with you. We also hope you will download our Meditation Moments when you get a chance which you can find on our website when you go to the sermons tab and click on this week’s sermon. -

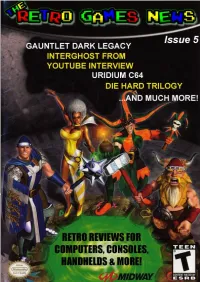

Trgnvol1issue5.Pdf

GAUNTLET DARK LEGACY 2 URIDIUM 22 INTERVIEW WITH ONE MAN & HIS DROID 23 INTERGHOST 7 DIE HARD TRILOGY 8 FAXANADU 10 SAMURAI JAZZ 10 TARGET RENEGADE 10 SUPER SPACE INVADERS 10 I am very excited to bring you this month’s issue of The Retro Games News as we have a great variety of reviews thanks to all of you who decided to write your own articles for the publication. Thanks also to Shaun who supplied us with a new logo. As I hope you will see, the layout of the Magazine has also had a bit of a facelift, my aim being to make it look as professional as possible, but still keeping the content laid back and fun to read. This month, we have an exclusive interview with the popular YouTuber Interghost, we have reviews spanning various systems and we also feature a new game which has been written by an independent publisher. Enjoy the read and happy retro gaming! Phil Wheatley - Editor GAUNTLET LEGACY Essentials Exclusive Offer! Test Drive Amiga Retail Box USA/NTSC Release Only $9.99 US plus shipping visit elisoftware.com and use promo code TRGNTD offer good until 8/15/2013 Your main channel is been around since 2006 which must be one of the oldest retrogaming channels INTERGHOST: around, what inspired you to start a channel? Yes, it’s been around for some time now, and time has just flown by! But as for being one of the oldest ADAM CLEAVER retrogaming channels, its not really. I was inspired by quite a few channels back before I decided to Adam Cleaver, better known as Interghost take the plunge into video making. -

Mediated Music Makers. Constructing Author Images in Popular Music

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Helsingin yliopiston digitaalinen arkisto Laura Ahonen Mediated music makers Constructing author images in popular music Academic dissertation to be publicly discussed, by due permission of the Faculty of Arts at the University of Helsinki in auditorium XII, on the 10th of November, 2007 at 10 o’clock. Laura Ahonen Mediated music makers Constructing author images in popular music Finnish Society for Ethnomusicology Publ. 16. © Laura Ahonen Layout: Tiina Kaarela, Federation of Finnish Learned Societies ISBN 978-952-99945-0-2 (paperback) ISBN 978-952-10-4117-4 (PDF) Finnish Society for Ethnomusicology Publ. 16. ISSN 0785-2746. Contents Acknowledgements. 9 INTRODUCTION – UNRAVELLING MUSICAL AUTHORSHIP. 11 Background – On authorship in popular music. 13 Underlying themes and leading ideas – The author and the work. 15 Theoretical framework – Constructing the image. 17 Specifying the image types – Presented, mediated, compiled. 18 Research material – Media texts and online sources . 22 Methodology – Social constructions and discursive readings. 24 Context and focus – Defining the object of study. 26 Research questions, aims and execution – On the work at hand. 28 I STARRING THE AUTHOR – IN THE SPOTLIGHT AND UNDERGROUND . 31 1. The author effect – Tracking down the source. .32 The author as the point of origin. 32 Authoring identities and celebrity signs. 33 Tracing back the Romantic impact . 35 Leading the way – The case of Björk . 37 Media texts and present-day myths. .39 Pieces of stardom. .40 Single authors with distinct features . 42 Between nature and technology . 45 The taskmaster and her crew. -

RELATIVE REALITY a Thesis

RELATIVE REALITY _______________ A thesis presented to the faculty of the College of Arts & Sciences of Ohio University _______________ In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Science ________________ Gary W. Steinberg June 2002 © 2002 Gary W. Steinberg All Rights Reserved This thesis entitled RELATIVE REALITY BY GARY W. STEINBERG has been approved for the Department of Physics and Astronomy and the College of Arts & Sciences by David Onley Emeritus Professor of Physics and Astronomy Leslie Flemming Dean, College of Arts & Sciences STEINBERG, GARY W. M.S. June 2002. Physics Relative Reality (41pp.) Director of Thesis: David Onley The consequences of Einstein’s Special Theory of Relativity are explored in an imaginary world where the speed of light is only 10 m/s. Emphasis is placed on phenomena experienced by a solitary observer: the aberration of light, the Doppler effect, the alteration of the perceived power of incoming light, and the perception of time. Modified ray-tracing software and other visualization tools are employed to create a video that brings this imaginary world to life. The process of creating the video is detailed, including an annotated copy of the final script. Some of the less explored aspects of relativistic travel—discovered in the process of generating the video—are discussed, such as the perception of going backwards when actually accelerating from rest along the forward direction. Approved: David Onley Emeritus Professor of Physics & Astronomy 5 Table of Contents ABSTRACT........................................................................................................4 -

Accused Killer's Trial Underway in Freelove Case Jury Selection Process Could Last Six Weeks, Prosecutors Say

BASEBALL TAKES TWO OF THREE FROM TECH - PAGE 7 TCU DAILY SKIFF TUESDAY, APRIL 4,1995 TEXAS CHRISTIAN UNIVERSITY, FORT WORTH, TEXAS 92NDYEAR,N0.95 Accused killer's trial underway in Freelove case Jury selection process could last six weeks, prosecutors say BY R. BRIAN SASSER Jackson said. "Everyone wants to TCU DAILY SKIFF keep prejudice ones that are in their favor." Jury selection began Monday in A forensic psychologist makes the capital murder trial of the man correlational studies about the back- accused of the November 1993 ground of potential jurors ami how killing of a TCU freshman and her those fac- friend. tors would Police and prosecutors say Darron affect the Deshone "Taz" Curl shot and killed prosecution 4^R «=-^ TCU freshman Channing Freelove or defense. and her friend Melanie Golchert for Jackson drugs on Nov. 13. 1993. said. The Freelove had gradualed from analyst also Paschal High School earlier that year can study KV-...'JC5!J and was a resident of Sherley Hall at and inter- the time of the killings. Golchen was pret the sub- not a TCU student, but had attended jects' body Channing Paschal. language Freelov e Curl, 23. has pleaded innocent of and facial the capital murder charges. Prosecu- expressions, tors Alan Levy and Terri Moore he said. TCU Dally Skiff/ Blake Sims could seek the death penalty in the Spokespersons m the district attor- Charlsie Mays, a senior case. ney's office could not say whether advertising/public rela- A spokeswoman in the Tarrant the prosecutors were using an ana- tions major, was inter- County District Attorney's office lyst. -

Second Hand Gaming Influence of Interactive Media

SECOND HAND GAMING INFLUENCE OF INTERACTIVE MEDIA BY METHOD OF CONSUMPTION By BRYAN TRUDE Bachelor of Arts in Mass Communications University of Central Oklahoma Edmond, Oklahoma 2013 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE May, 2017 SECOND HAND GAMING INFLUENCE OF INTERACTIVE MEDIA BY METHOD OF CONSUMPTION Thesis Approved: Dr. Danny Shipka Thesis Adviser Dr. Cynthia Wang Dr. Lori McKinnon ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank the faculty and staff of the Oklahoma State University School of Media and Strategic Communications, the College of Arts and Sciences, and the Graduate College for all of their guidance and support through this two-year journey. Individually, I would like to thank Dr. Danny Shipka, Dr. Cynthia Wang, and Dr. Lori McKinnon for their service on my thesis committee, along with Dr. Stan Ketterer, a committee member who had to withdraw for medical reasons. Keep on tickin’, doc. I would also like to thank Dr. Craig Freeman, director of the School of Media and Strategic Communications, for never being too busy to sit down and chat about whatever, and for overwhelming me with your daily dose of energy and passion for everything SMSC. Dr. Shipka, thank you for leading me by the hand through this process like an owner leading a scared puppy, and for reassuring me when I got too far inside my own head. I could have never done this without you, and everything I become from here on out is because of what you’ve helped me to build. -

Nintendo Co., Ltd

Nintendo Co., Ltd. Financial Results Briefing for the Nine-Month Period Ended December 2008 (Briefing Date: 2009/1/30) Supplementary Information [Note] Forecasts announced by Nintendo Co., Ltd. herein are prepared based on management's assumptions with information available at this time and therefore involve known and unknown risks and uncertainties. Please note such risks and uncertainties may cause the actual results to be materially different from the forecasts (earnings forecast, dividend forecast and other forecasts). Nintendo Co., Ltd. Consolidated Statements of Income Transition million yen FY3/2005 FY3/2006 FY3/2007 FY3/2008 FY3/2009 Apr.-Dec.'04 Apr.-Dec.'05 Apr.-Dec.'06 Apr.-Dec.'07 Apr.-Dec.'08 Net sales 419,373 412,339 712,589 1,316,434 1,536,348 Cost of sales 232,495 237,322 411,862 761,944 851,283 Gross margin 186,877 175,017 300,727 554,489 685,065 (Gross margin ratio) (44.6%) (42.4%) (42.2%) (42.1%) (44.6%) Selling, general, and administrative expenses 83,771 92,233 133,093 160,453 183,734 Operating income 103,106 82,783 167,633 394,036 501,330 (Operating income ratio) (24.6%) (20.1%) (23.5%) (29.9%) (32.6%) Other income 15,229 64,268 53,793 37,789 28,295 (of which foreign exchange gains) (4,778) (45,226) (26,069) (143) ( - ) Other expenses 2,976 357 714 995 177,137 (of which foreign exchange losses) ( - ) ( - ) ( - ) ( - ) (174,233) Income before income taxes and extraordinary items 115,359 146,694 220,713 430,830 352,488 (Income before income taxes and extraordinary items ratio) (27.5%) (35.6%) (31.0%) (32.7%) (22.9%) Extraordinary gains 1,433 6,888 1,047 3,830 98 Extraordinary losses 1,865 255 27 2,135 6,171 Income before income taxes and minority interests 114,927 153,327 221,734 432,525 346,415 Income taxes 47,260 61,176 89,847 173,679 133,856 Minority interests -91 -34 -29 -83 35 Net income 67,757 92,185 131,916 258,929 212,524 (Net income ratio) (16.2%) (22.4%) (18.5%) (19.7%) (13.8%) - 1 - Nintendo Co., Ltd.