A Report on Asia Pulp and Paper's Operations in Sumatra, Indonesia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Siak River in Central Sumatra, Indonesia

Tropical blackwater biogeochemistry: The Siak River in Central Sumatra, Indonesia Dissertation zur Erlangung des Doktorgrades der Naturwissenschaften (Dr. rer. nat.) vorgelegt von Antje Baum Bremen 2008 Advisory Committee: 1. Reviewer: Dr. Tim Rixen Center for Tropical Marine Ecology (ZMT), Bremen, Germany 2. Reviewer: Prof. Dr. Wolfgang Balzer University of Bremen 1. Examiner: Prof. Dr. Venugopalan Ittekkot Center for Tropical Marine Ecology (ZMT), Bremen, Germany 2. Examiner: Dr. Daniela Unger Center for Tropical Marine Ecology (ZMT), Bremen, Germany I Contents Summary .................................................................................................................... III Zusammenfassung...................................................................................................VII 1. Introduction........................................................................................................ 11 2. Published and submitted papers..................................................................... 15 2.1. Sources of dissolved inorganic nutrients in the peat-draining river Siak, Central Sumatra, Indonesia ................................................................................... 15 2.2. The Siak, a tropical black water river in central Sumatra on the verge of anoxia ..................................................................................................................... 31 2.3. Relevance of peat draining rivers in central Sumatra for riverine input of dissolved organic carbon into the -

Chapter 2 Political Development and Demographic Features

Cover Page The handle http://hdl.handle.net/1887/36062 holds various files of this Leiden University dissertation Author: Xiaodong Xu Title: Genesis of a growth triangle in Southeast Asia : a study of economic connections between Singapore, Johor and the Riau Islands, 1870s – 1970s Issue Date: 2015-11-04 Chapter 2 Political Development and Demographic Features A unique feature distinguishing this region from other places in the world is the dynamic socio-political relationship between different ethnic groups rooted in colonial times. Since then, both conflict and compromise have occurred among the Europeans, Malays and Chinese, as well as other regional minorities, resulting in two regional dichotomies: (1) socially, the indigenous (Malays) vs. the outsiders (Europeans, Chinese, etc.); (2) politically, the rulers (Europeans and Malay nobles) vs. those ruled (Malays, Chinese). These features have a direct impact on economic development. A retrospective survey of regional political development and demographic features are therefore needed to provide a context for the later analysis of economic development. 1. Political development The formation of Singapore, Johor and the Riau Islands was far from a sudden event, but a long process starting with the decline of the Johor-Riau Sultanate in the late eighteenth century. In order to reveal the coherency of regional political transformations, the point of departure of this political survey begins much earlier than the researched period here. Political Development and Demographic Features 23 The beginning of Western penetration (pre-1824) Apart from their geographical proximity, Singapore, Johor and the Riau Islands had also formed a natural and inseparable part of various early unified kingdoms in Southeast Asia. -

Only Yesterday in Jakarta: Property Boom and Consumptive Trends in the Late New Order Metropolitan City

Southeast Asian Studies, Vol. 38, No.4, March 2001 Only Yesterday in Jakarta: Property Boom and Consumptive Trends in the Late New Order Metropolitan City ARAI Kenichiro* Abstract The development of the property industry in and around Jakarta during the last decade was really conspicuous. Various skyscrapers, shopping malls, luxurious housing estates, condominiums, hotels and golf courses have significantly changed both the outlook and the spatial order of the metropolitan area. Behind the development was the government's policy of deregulation, which encouraged the active involvement of the private sector in urban development. The change was accompanied by various consumptive trends such as the golf and cafe boom, shopping in gor geous shopping centers, and so on. The dominant values of ruling elites became extremely con sumptive, and this had a pervasive influence on general society. In line with this change, the emergence of a middle class attracted the attention of many observers. The salient feature of this new "middle class" was their consumptive lifestyle that parallels that of middle class as in developed countries. Thus it was the various new consumer goods and services mentioned above, and the new places of consumption that made their presence visible. After widespread land speculation and enormous oversupply of property products, the property boom turned to bust, leaving massive non-performing loans. Although the boom was not sustainable and it largely alienated urban lower strata, the boom and resulting bust represented one of the most dynamic aspect of the late New Order Indonesian society. I Introduction In 1998, Indonesia's "New Order" ended. -

Pt Inti Indosawit Subur – Tungkal Ulu Group and Scheme Smallholders

PUBLIC SUMMARY REPORT RSPO SECOND ANNUAL SURVEILLANCE ASSESSMENT (ASA2) PT INTI INDOSAWIT SUBUR – TUNGKAL ULU GROUP AND SCHEME SMALLHOLDERS Jambi Province, Sumatra, INDONESIA Report Author: Haeruddin Tahir – September 2014 BSI Group Singapore Pte Ltd (Co. Reg. 1995 02096‐N) PT. BSI Group Indonesia 1 Robinson Road Menara Bidakara 2, 17th Floor Unit 5 AIA Tower #15‐01 Jl. Jend. Gatot Subroto Kav. 71‐73 Singapore 048542 Komplek Bidakara, Pancoran Tel +65 6270 0777 Jakarta Selatan 12870 ‐ Indonesia Fax +65 6270 2777 Tel +62 21 8379 3174 ‐ 77 www.bsigroup.sg Fax +62 21 8379 3287 Aryo Gustomo: [email protected] TABLE of CONTENTS page № SUMMARY......................................................................................................................................................... 1 Abbreviations Used........................................................................................................................................... 1 1.0 SCOPE OF CERTIFICATION ASSESSMENT.............................................................................................. 1 1.1 National Interpretation Used...................................................................................................................... 1 1.2 Certification Scope...................................................................................................................................... 1 1.3 Location and Maps.................................................................................................................................... -

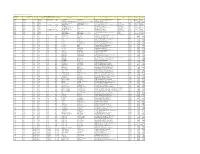

Colgate Palmolive List of Mills As of June 2018 (H1 2018) Direct

Colgate Palmolive List of Mills as of June 2018 (H1 2018) Direct Supplier Second Refiner First Refinery/Aggregator Information Load Port/ Refinery/Aggregator Address Province/ Direct Supplier Supplier Parent Company Refinery/Aggregator Name Mill Company Name Mill Name Country Latitude Longitude Location Location State AgroAmerica Agrocaribe Guatemala Agrocaribe S.A Extractora La Francia Guatemala Extractora Agroaceite Extractora Agroaceite Finca Pensilvania Aldea Los Encuentros, Coatepeque Quetzaltenango. Coatepeque Guatemala 14°33'19.1"N 92°00'20.3"W AgroAmerica Agrocaribe Guatemala Agrocaribe S.A Extractora del Atlantico Guatemala Extractora del Atlantico Extractora del Atlantico km276.5, carretera al Atlantico,Aldea Champona, Morales, izabal Izabal Guatemala 15°35'29.70"N 88°32'40.70"O AgroAmerica Agrocaribe Guatemala Agrocaribe S.A Extractora La Francia Guatemala Extractora La Francia Extractora La Francia km. 243, carretera al Atlantico,Aldea Buena Vista, Morales, izabal Izabal Guatemala 15°28'48.42"N 88°48'6.45" O Oleofinos Oleofinos Mexico Pasternak - - ASOCIACION AGROINDUSTRIAL DE PALMICULTORES DE SABA C.V.Asociacion (ASAPALSA) Agroindustrial de Palmicutores de Saba (ASAPALSA) ALDEA DE ORICA, SABA, COLON Colon HONDURAS 15.54505 -86.180154 Oleofinos Oleofinos Mexico Pasternak - - Cooperativa Agroindustrial de Productores de Palma AceiteraCoopeagropal R.L. (Coopeagropal El Robel R.L.) EL ROBLE, LAUREL, CORREDORES, PUNTARENAS, COSTA RICA Puntarenas Costa Rica 8.4358333 -82.94469444 Oleofinos Oleofinos Mexico Pasternak - - CORPORACIÓN -

Danish Banks and Palm Oil and Pulp & Paper in Indonesia

Danish banks and palm oil and pulp & paper in Indonesia A research paper prepared for WWF International December 2001 Jan Willem van Gelder Profundo De Bloemen 24 1902 GV Castricum The Netherlands Tel: +31-251-658385 Fax: +31-251-658386 E-mail: [email protected] Contents Summary ..................................................................................................................i Introduction................................................................................................................1 Chapter 1 Influence assessment of financial institutions....................................2 1.1 The financing of companies....................................................................................2 1.2 Private financial institutions ...................................................................................3 1.3 Public financial institutions.....................................................................................5 1.4 Categories of financial services .............................................................................5 1.4.1 Services related to acquiring equity ...............................................................5 1.4.2 Services related to acquiring debt ..................................................................6 1.4.3 Other financial services ..................................................................................7 1.5 Assessing the influence of financial institutions..................................................9 1.5.1 The present role of financial -

Chinese Big Business in Indonesia Christian Chua

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by ScholarBank@NUS CHINESE BIG BUSINESS IN INDONESIA THE STATE OF CAPITAL CHRISTIAN CHUA NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF SINGAPORE 2006 CHINESE BIG BUSINESS IN INDONESIA THE STATE OF CAPITAL CHRISTIAN CHUA (M.A., University of Göttingen/Germany) A THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF SOCIOLOGY NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF SINGAPORE 2006 i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Throughout the years working on this study, the list of those who ought to be mentioned here grew tremendously. Given the limited space, I apologise that these acknowledgements thus have to remain somewhat incomplete. I trust that those whose names should, but do not, ap- pear here know that I am aware of and grateful for the roles they played for me and for this thesis. However, a few persons cannot remain unstated. Most of all, I owe my deepest thanks to my supervisor Vedi Hadiz. Without him, I would not have begun work on this topic and in- deed, may have even given up along the way. His patience and knowledgeable guidance, as well as his sharp mind and motivation helped me through many crises and phases of despair. I am thankful, as well, for the advice and help of Mary Heidhues, Anthony Reid, Noorman Ab- dullah, and Kelvin Low, who provided invaluable feedback on early drafts. During my fieldwork in Indonesia, I was able to work as a Research Fellow at the Centre for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) in Jakarta thanks to the kind support of its direc- tor, Hadi Soesastro. -

Mill List - 2020

General Mills - Mill List - 2020 General Mills July 2020 - December 2020 Parent Mill Name Latitude Longitude RSPO Country State or Province District UML ID 3F Oil Palm Agrotech 3F Oil Palm Agrotech 17.00352 81.46973 No India Andhra Pradesh West Godavari PO1000008590 Aathi Bagawathi Manufacturing Abdi Budi Mulia 2.051269 100.252339 No Indonesia Sumatera Utara Labuhanbatu Selatan PO1000004269 Aathi Bagawathi Manufacturing Abdi Budi Mulia 2 2.11272 100.27311 No Indonesia Sumatera Utara Labuhanbatu Selatan PO1000008154 Abago Extractora Braganza 4.286556 -72.134083 No Colombia Meta Puerto Gaitán PO1000008347 Ace Oil Mill Ace Oil Mill 2.91192 102.77981 No Malaysia Pahang Rompin PO1000003712 Aceites De Palma Aceites De Palma 18.0470389 -94.91766389 No Mexico Veracruz Hueyapan de Ocampo PO1000004765 Aceites Morichal Aceites Morichal 3.92985 -73.242775 No Colombia Meta San Carlos de Guaroa PO1000003988 Aceites Sustentables De Palma Aceites Sustentables De Palma 16.360506 -90.467794 No Mexico Chiapas Ocosingo PO1000008341 Achi Jaya Plantations Johor Labis 2.251472222 103.0513056 No Malaysia Johor Segamat PO1000003713 Adimulia Agrolestari Segati -0.108983 101.386783 No Indonesia Riau Kampar PO1000004351 Adimulia Agrolestari Surya Agrolika Reksa (Sei Basau) -0.136967 101.3908 No Indonesia Riau Kuantan Singingi PO1000004358 Adimulia Agrolestari Surya Agrolika Reksa (Singingi) -0.205611 101.318944 No Indonesia Riau Kuantan Singingi PO1000007629 ADIMULIA AGROLESTARI SEI TESO 0.11065 101.38678 NO INDONESIA Adimulia Palmo Lestari Adimulia Palmo Lestari -

This Thesis Has Been Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for a Postgraduate Degree (E.G

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. At the Edge of Mangrove Forest: The Suku Asli and the Quest for Indigeneity, Ethnicity and Development Takamasa Osawa PhD in Social Anthropology University of Edinburgh 2016 Declaration Page This is to certify that this thesis has been composed by me and is completely my work. No part of this thesis has been submitted for any other degree or professional qualification. 30th January 2016 Takamasa Osawa PhD Candidate School of Social & Political Science University of Edinburgh ii Abstract This thesis explores the emergence of indigeneity among a group of post-foragers living on the eastern coast of Sumatra. In the past, despite the lack of definite ethnic boundaries and the fluidity of their identity, they were known as Utan (‘Forest’) or Orang Utan (‘Forest People’). -

Peta Bisnis Perusahaan Konglomerat Indonesia

Gelael & Djarum First Pacific Salim Heidelberg afiliasi Rudy Tanudjaja Group Capital Group (anthony, dll) Cement Group © Investorsadar.com - 2018 58% 51% · Content informasi di sini berdasarkan riset penulis. Penulis 73% 2% tidak bertanggung jawab terhadap dampak dari penggunaan Sarana Menara Bank Central Asia Indonesia Prima Indoritel Makmur Indofood Indofood Indomobil indocement Nusantara informasi ini (BBCA) Property (OMRE) (DNET) Agri Resources Ltd (INDF) (IMAS) (INTP) · Data dan Informasi akan terus diupdate sehingga diharapkan (TOWR) akan mencakup seluruh perusahaan yang listing di bursa 36% 73% 89% saham Indonesia (IDX) 31% 7% 44% 80% Fast Food Ind Nippon Indosari Salim Ivomas Indofood CBP Indomobil Multi (FAST) (ROTI) Pratama (SIMP) (ICBP) Jasa (IMJS) 59% PP London Sumatra (LSIP) PROVESTMENT Keluarga Sudono Lippo Group Cyport Limited LIMITED Salim 19% 27% 49% Gajah Tunggal Mitra Adiperkasa Lippo Karawaci Multipolar (GJTL) (MAPI) (LPKR) (MLPL) 54% 60% 26% 62% 34% 80% 49% 17% 50% 20% 33% Siloam Gowa Makassar Multipolar Matahari Polychem Lippo Cikarang First Media Matahari Putra Bank National Multifiling Mitra International Tourism Dev Technology Department Store Indonesia (ADMG) (LPCK) (KBLV) Prima (MPPA) Nobu (NOBU) Indonesia (MFMI) Hospitals (SILO) (GMTD) (MPPT) (LPPF) 34% Link Net (LINK) MNC investama Sinar Mas Group - (BHIT) Eka Tjipta Widjaja 39% 50% 53% 69% Indonesian Purinusa Duta Permana Sinar Mas Bumi Serpong MNC Land Purimas Sasmita Sinar Mas Tunggal Paradise Property Global Mediacom MNC Kapital Ekapersada Makmur Cakrawala -

Carbon Leaching from Tropical Peat Soils and Consequences for Carbon Balances

ORIGINAL RESEARCH published: 13 July 2016 doi: 10.3389/feart.2016.00074 Carbon Leaching from Tropical Peat Soils and Consequences for Carbon Balances Tim Rixen 1, 2*, Antje Baum 1, Francisca Wit 1 and Joko Samiaji 3 1 Leibniz Center for Tropical Marine Ecology, Bremen, Germany, 2 Department of Biogeochemistry, Institute of Geology, University of Hamburg, Hamburg, Germany, 3 Faculty of Fishery and Marine Science, University of Riau, Pekanbaru, Indonesia Drainage and deforestation turned Southeast (SE) Asian peat soils into a globally important CO2 source, because both processes accelerate peat decomposition. Carbon losses through soil leaching have so far not been quantified and the underlying processes have hardly been studied. In this study, we use results derived from nine expeditions to six Sumatran rivers and a mixing model to determine leaching processes in tropical peat soils, which are heavily disturbed by drainage and deforestation. Here we show that a reduced evapotranspiration and the resulting increased freshwater discharge in addition to the supply of labile leaf litter produced by re-growing secondary forests increase leaching of carbon by ∼200%. Enhanced freshwater fluxes and leaching of labile leaf litter from secondary vegetation appear to contribute 38 and 62% to the total increase, respectively. Decomposition of leached labile DOC can lead to hypoxic conditions in Edited by: Francien Peterse, rivers draining disturbed peatlands. Leaching of the more refractory DOC from peat is an Universiteit Utrecht, Netherlands irrecoverable loss of soil that threatens the stability of peat-fringed coasts in SE Asia. Reviewed by: Keywords: tropical peat soil, degradation, secondary vegetation, carbon loss, Sumatra, Indonesia William Patrick Gilhooly III, Indiana University Purdue University Indianapolis, USA Chris Evans, INTRODUCTION Centre for Ecology and Hydrology, UK *Correspondence: Pristine peat swamp forests are rare with only circa 10% left on the islands of Borneo and Sumatra Tim Rixen (Miettinen and Liew, 2010). -

A Abdullah Ali, 227, 288, 350, 359, 390 Abdurrahman Wahid (Gus Dur)

INDEX A anti-Chinese riots, 74, 222–23, 381–84, Abdullah Ali, 227, 288, 350, 359, 390 393 Abdurrahman Wahid (Gus Dur), 245, see also Malari riots; May 1998 riots 269, 416, 417, 429–32, 434–35, Anthony (Anthoni) Salim, see Salim, 438–39, 444, 498, 515 Anthony Aburizal Bakrie, 393, 399, 402 Apkindo (Indonesian Wood Panel Achmad Thahir, 200 Association), 4 Achmad Tirtosudiro, 72, 166–67 Aquino, Cory, 460–61 Adam Malik, 57, 139, 164–66 Arbamass Multi Invesco, 341 Adi Andoyo, 380 Ari H. Wibowo Hardojudanto, 340 Adi Sasono, 400, 408 Arief Husni, 71, 91 Adrianus Mooy, 246 Arifin Siregar, 327 Agus Lasmono, 113 Army Strategic Reserve Command Agus Nursalim, 91 (Kostrad), 56, 59, 64, 72–73, 108, Ahmad Habir, 299 111, 116, 166, 171, 176, 209 Akbar Tanjung, 257, 393, 395 Argha Karya Prima, 120–21 Alamsjah Ratu Prawiranegara, 65–66, Argo Manunggal Group, 34 68, 69, 72 A.R. Soehoed, 328 “Ali Baba” relationship, 50 ASEAN (Association of Southeast Ali Murtopo, 57, 60, 65–66, 69–70, Asian Nations), 155, 362, 498 73–75, 117, 153, 222–23, 326 AsiaMedic, 474 Ali Sadikin, 224, 238–39 Asian financial crisis, 33, 85, 87, 113, Ali Wardhana, 329, 393 121–23, 130, 147, 193, 228, 248, American Express Bank, 192, 262, 276, 284, 286, 290–91, 311, 329, 271 336, 349, 352, 354–67, 369, 392, Amex Bancom, 262–64 405, 466, 468, 473, 480 Amien Rais, 381, 387–88 Aspinall, Edward, 496 Ando, Koki, 410–11 Association of Indonesian Muslim Ando, Momofuku, 292, 410 Intellectuals (ICMI), 379 Andreas Harsono, 351 Association of Southeast Asian Andrew Riady, 225 Nations, see ASEAN