Revised Settlement Hisar

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

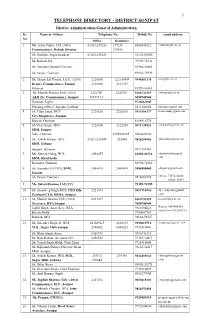

1 TELEPHONE DIRECTORY - DISTRICT SONIPAT District Administration/General Administration Sr

1 TELEPHONE DIRECTORY - DISTRICT SONIPAT District Administration/General Administration Sr. Name of Officer Telephone No. Mobile No. email address No. Office Residence 1. Ms. Anita Yadav, IAS (2004) 01262-255253 279233 8800540222 [email protected] Commissioner, Rohtak Division 274555 Sh. Gulshan, Superintendent 01262-255253 94163-80900 Sh. Rakesh, PA 99925-72241 Sh. Surender, Reader/Commnr. 98964-28485 Sh. Sanjay, Gunman 89010-19999 2. Sh. Shyam Lal Poonia, I.A.S., (2010) 2220500 2221500-F 9996801370 [email protected] Deputy Commissioner, Sonipat 2220006 2221255 Gunman 83959-00363 3. Sh. Munish Sharma, IAS, (2014) 2222700 2220701 8368733455 [email protected] Addl. Dy. Commissioner, Sonipat 2222701,2 9650746944 Gunman, Jagbir 9728661005 Planning Officer, Joginder Lathwal 9813303608 [email protected] 4. Sh. Uday Singh, HCS 2220638 2220538 9315304377 [email protected] City Magistrate, Sonipat Rakesh, Gunman 8168916374 5. Sh .Vijay Singh, HCS 2222100 2222300 9671738833 [email protected] SDM, Sonipat Inder, Gunman 8395900365 9466821680 6. Sh. Ashish Kumar, HCS, 01263-252049 252050 9416288843 [email protected] SDM, Gohana Sanjeev, Gunman 9813759163 7. Ms. Shweta Suhag, HCS, 2584055 82850-00716 sdmkharkhoda@gmail. SDM, Kharkhoda com Ravinder, Gunman 80594-76260 8. Sh . Surender Pal, HCS, SDM, 2460810 2460800 9888885445 [email protected] Ganaur Sh. Pawan, Gunman 9518662328 Driver- 73572-04014 81688-19475 9. Ms. Saloni Sharma, IAS (UT) 78389-90155 10. Sh. Amardeep Singh, HCS, CEO Zila 2221443 9811710744 dy.ceo.zp.snp@gmail. Parishad CEO, DRDA, Sonipat com 11. Sh. Munish Sharma, IAS, (2014) 2221937 8368733455 [email protected] Secretary, RTA Sonipat 9650746944 Jagbir Singh, Asstt. Secy. RTA 9463590022 Rakesh-9467446388 Satbir Dvr-9812850796 Rajesh Malik 7700007784 Ramesh, MVI 94668-58527 12. -

Final Cluster List

FINAL CLUSTER LIST Sr District Block Cluster Cluster Head School Name UDISECode School Name Distance Head From School CRC in Code KM 1 JHAJJAR BAHADURGARH 6150206303 GGSSS BAHADUR GARH 6150204004 GGHS SIDIPUR LOWA KALAN 5 2 JHAJJAR BAHADURGARH 6150206303 GGSSS BAHADUR GARH 6150206303 GGSSS BAHADUR GARH 0 3 JHAJJAR BAHADURGARH 6150206303 GGSSS BAHADUR GARH 6150200702 GHS BALOUR 2 4 JHAJJAR BAHADURGARH 6150206303 GGSSS BAHADUR GARH 6150202303 GHS ISHARHERI 7 5 JHAJJAR BAHADURGARH 6150206303 GGSSS BAHADUR GARH 6150205803 GHS SIDIPUR 4 6 JHAJJAR BAHADURGARH 6150206303 GGSSS BAHADUR GARH 6150205602 GMS SARAI ORANGABAD 3 7 JHAJJAR BAHADURGARH 6150206303 GGSSS BAHADUR GARH 6150200701 GPS BALOUR 2 8 JHAJJAR BAHADURGARH 6150206303 GGSSS BAHADUR GARH 6150202301 GPS ISHARHERI 7 9 JHAJJAR BAHADURGARH 6150206303 GGSSS BAHADUR GARH 6150206304 GPS MAIN BAZAR B.GARH 0 10 JHAJJAR BAHADURGARH 6150206303 GGSSS BAHADUR GARH 6150205601 GPS SARAI ORANGABAD 3 11 JHAJJAR BAHADURGARH 6150206303 GGSSS BAHADUR GARH 6150205801 GPS SIDIPUR 4 12 JHAJJAR BAHADURGARH 6150206303 GGSSS BAHADUR GARH 6150204001 GPS SIDIPUR LOWA KALAN 5 13 JHAJJAR BAHADURGARH 6150206303 GGSSS BAHADUR GARH 6150206314 GPS TABELA B.GARH 0 14 JHAJJAR BAHADURGARH 6150202604 GGSSS JASSORPUR KHERI 6150202602 GGPS JASSOUR KHERI 0 15 JHAJJAR BAHADURGARH 6150202604 GGSSS JASSORPUR KHERI 6150203801 GGPS LOHAR HERI 3 16 JHAJJAR BAHADURGARH 6150202604 GGSSS JASSORPUR KHERI 6150205002 GGPS NILOTHI 2 17 JHAJJAR BAHADURGARH 6150202604 GGSSS JASSORPUR KHERI 6150202604 GGSSS JASSORPUR KHERI 0 18 JHAJJAR BAHADURGARH -

Agromet Advisory Bulletin for the State of Haryana Bulletin No

Agromet Advisory Bulletin for the State of Haryana Bulletin No. 77/2021 Issued on 24.09.2021 Part A: Realized and forecast weather Summary of past weather over the State during (21.09.2021 to 23.09.2021) Light to Moderate Rainfall occured at many places with Moderate to Heavy rainfall occurred at isolated places on 21th and at most places on 22th & 23th in the state. Mean Maximum Temperatures varied between 30-32oC in Eastern Haryana which were 01-02oC below normal and in Western Haryana between 33-35 oC which were 01-02 oC below normal. Mean Minimum Temperatures varied between 24-26 oC Eastern Haryana which were 02-03oC above normal and in Western Haryana between 24-26 oC which were 00-01 oC above normal. Chief amounts of rainfall (in cms):- 21.09.2021- Gohana (dist Sonepat) 9, Khanpur Rev (dist Sonepat) 7, Panipat (dist Panipat) 7, Kalka (dist Panchkula) 5, Dadri (dist Charkhi Dadri) 5, Panchkula (dist Panchkula) 5, Ganaur (dist Sonepat) 4, Israna (dist Panipat) 4, Fatehabad (dist Fatehabad) 4, Madluda Rev (dist Panipat) 4, Panchkula Aws (dist Panchkula) 3, Sonepat (dist Sonepat) 3, Naraingarh (dist Ambala) 3, Beri (dist Jhajjar) 2, Sirsa Aws (dist Sirsa) 2, Kharkoda (dist Sonepat) 2, Jhahhar (dist Jhajjar) 2, Uklana Rly (dist Hisar) 2, Uklana Rev (dist Hisar) 2, Raipur Rani (dist Panchkula) 2, Jhirka (dist Nuh) 2, Hodal (dist Palwal) 2, Rai Rev (dist Sonepat) 2, Morni (dist Panchkula) 2, Sirsa (dist Sirsa) 1, Hassanpur (dist Palwal) 1, Partapnagar Rev (dist Yamuna Nagar) 1, Bahadurgarh (dist Jhajjar) 1, Jagdishpur Aws (dist Sonepat) -

Haryana Highway Upgrading Project Project Coordinationconsultancy

PUBLIC WORKS DEPARTMENT (B&R) GOVERNMENT OF HARYANA, INDIA Public Disclosure Authorized HaryanaHighway Upgrading Project ProjectCoordination Consultancy SECTORALENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT Public Disclosure Authorized FINAL REPORT CMA,,ISA \ Public Disclosure Authorized VOLUMEI11 APPENDICES SEPTEMBER 1997 Public Disclosure Authorized CarlBro Internationalals - (2,inassociation with BCEOM,Louis Berger International Inc. and J adBroGrot ConsultingEngineering Services (India)Ltd. PUBLIC WORKS DEPARTMENT (B&R) GOVERNMENT OF HARYANA, INDIA Haryana Highway Upgrading Project Project CoordinationConsultancy SECTORALENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT FINALREPORT VOLUMEII APPENDICES SEPTEMBER1997 ~ CarlBro International als in associationwith BCEOM,Louis Berger International Inc. and J CarlBroGroup ConsultingEngineering Services (India) Ltd. VOLUME It - APPENDICES TO MAIN REPORT Number Appendix Page (s) Appendix I EnvironmentalAttributes of ROW corridors Al-I Appendix2 EnvironmentalStandards A2-1 Appendix3 Contract RelatedDocumentation A3-1 Appendix4 EnvironmentalManagement Checklist A4-1 Appendix5 EnvironmentalClauses to BiddingDocuments A5-1 Appendix6 List of Consultations A6-l tiaryana tiignway upgraing rrojecr A%lirivirunmentnai AFnnDUTCS 01 KU W APPENDIX 1 Environmental Attributes of ROW Corridors HaryanaHighwey Uprading Project Appendix I ENVIRONMENTALATTRIBUTES ON 20 KM CORRIDOR SEGMENT-2: SHAHZADPUR-SAHA(15.6 KM) ATrRIBUTES LOCATION & DESCRIPTION S.O.L Map Reference 53F/3 53B115 Topography Roadpase throughmore or lessplain are Erosional Features None shownin SOI mnap Water odies - AmnrChoaRiver at6km;Markandari sat0-10kmoff4km; Dhanaurrierat km0-16off7 :Badali iver at km 0-16 off5 krn; Dangri river at km 016 off 10km; Begnarive at ht 0-1 off4 km Natural Vegetation None shownin SOImnap Agriculture Road pas thruh cultivatedland on both sides Industry None shownti SOImaps Urban Settlement Shahz dpurTownship: At km 15; Saa township:at km 15 Communication None shownin SOI maps PowerUne Notshown in SOl maps Social Institution/Defence/Alrport Noneshown in SOI maps A. -

Government of Haryana Department of Revenue & Disaster Management

Government of Haryana Department of Revenue & Disaster Management DISTRICT DISASTER MANAGEMENT PLAN Sonipat 2016-17 Prepared By HARYANA INSTITUTE OF PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION, Plot 76, HIPA Complex, Sector 18, Gurugram District Disaster Management Plan, Sonipat 2016-17 ii District Disaster Management Plan, Sonipat 2016-17 iii District Disaster Management Plan, Sonipat 2016-17 Contents Page No. 1 Introduction 01 1.1 General Information 01 1.2 Topography 01 1.3 Demography 01 1.4 Climate & Rainfall 02 1.5 Land Use Pattern 02 1.6 Agriculture and Cropping Pattern 02 1.7 Industries 03 1.8 Culture 03 1.9 Transport and Connectivity 03 2 Hazard Vulnerability & Capacity Analysis 05 2.1 Hazards Analysis 05 2.2 Hazards in Sonipat 05 2.2.1 Earthquake 05 2.2.2 Chemical Hazards 05 2.2.3 Fires 06 2.2.4 Accidents 06 2.2.5 Flood 07 2.2.6 Drought 07 2.2.7 Extreme Temperature 07 2.2.8 Epidemics 08 2.2.9 Other Hazards 08 2.3 Hazards Seasonality Map 09 2.4 Vulnerability Analysis 09 2.4.1 Physical Vulnerability 09 2.4.2 Structural vulnerability 10 2.4.3 Social Vulnerability 10 2.5 Capacity Analysis 12 2.6 Risk Analysis 14 3 Institutional Mechanism 16 3.1 Institutional Mechanisms at National Level 16 3.1.1 Disaster Management Act, 2005 16 3.1.2 Central Government 16 3.1.3 Cabinet Committee on Management of Natural Calamities 18 (CCMNC) and the Cabinet Committee on Security (CCS) 3.1.4 High Level Committee (HLC) 18 3.1.5 National Crisis Management Committee (NCMC) 18 3.1.6 National Disaster Management Authority (NDMA) 18 3.1.7 National Executive Committee (NEC) 19 -

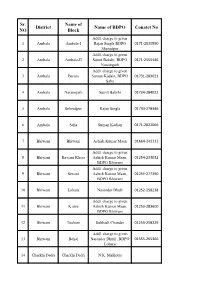

Sr. NO District Name of Block Name of BDPO Conatct No

Sr. Name of District Name of BDPO Conatct No NO Block Addl. charge to given 1 Ambala Ambala-I Rajan Singla BDPO 0171-2530550 Shazadpur Addl. charge to given 2 Ambala Ambala-II Sumit Bakshi, BDPO 0171-2555446 Naraingarh Addl. charge to given 3 Ambala Barara Suman Kadain, BDPO 01731-283021 Saha 4 Ambala Naraingarh Sumit Bakshi 01734-284022 5 Ambala Sehzadpur Rajan Singla 01734-278346 6 Ambala Saha Suman Kadian 0171-2822066 7 Bhiwani Bhiwani Ashish Kumar Maan 01664-242212 Addl. charge to given 8 Bhiwani Bawani Khera Ashish Kumar Maan, 01254-233032 BDPO Bhiwani Addl. charge to given 9 Bhiwani Siwani Ashish Kumar Maan, 01255-277390 BDPO Bhiwani 10 Bhiwani Loharu Narender Dhull 01252-258238 Addl. charge to given 11 Bhiwani K airu Ashish Kumar Maan, 01253-283600 BDPO Bhiwani 12 Bhiwani Tosham Subhash Chander 01253-258229 Addl. charge to given 13 Bhiwani Behal Narender Dhull , BDPO 01555-265366 Loharu 14 Charkhi Dadri Charkhi Dadri N.K. Malhotra Addl. charge to given 15 Charkhi Dadri Bond Narender Singh, BDPO 01252-220071 Charkhi Dadri Addl. charge to given 16 Charkhi Dadri Jhoju Ashok Kumar Chikara, 01250-220053 BDPO Badhra 17 Charkhi Dadri Badhra Jitender Kumar 01252-253295 18 Faridabad Faridabad Pardeep -I (ESM) 0129-4077237 19 Faridabad Ballabgarh Pooja Sharma 0129-2242244 Addl. charge to given 20 Faridabad Tigaon Pardeep-I, BDPO 9991188187/land line not av Faridabad Addl. charge to given 21 Faridabad Prithla Pooja Sharma, BDPO 01275-262386 Ballabgarh 22 Fatehabad Fatehabad Sombir 01667-220018 Addl. charge to given 23 Fatehabad Ratia Ravinder Kumar, BDPO 01697-250052 Bhuna 24 Fatehabad Tohana Narender Singh 01692-230064 Addl. -

Haryana), India

AL SC R IEN TU C A E N F D O N U A N D D Journal of Applied and Natural Science 6 (1): 6-11 (2014) A E I T L JANS I O P N P A ANSF 2008 Assessment of soil physical health and productivity of Kharkhoda and Gohana blocks of Sonipat district (Haryana), India Rakesh Kumar*, Pramila Aggarwal, Ravendra Singh, Debashis Chakraborty, Ranjan Bhattacharya, R. N. Garg, Kalpana H. Kamble and Brijesh Yadav Division of Agricultural Physics, Indian Agricultural Research Institute, New Delhi-110012, INDIA *Corresponding author. E-mail: [email protected] Received: November 6, 2013; Revised received: January 2, 2014; Accepted: January 5, 2014 Abstract: In order to assess soil health of Kharkhoda and Gohana blocks of Sonipat district (a part of western Yamuna canal irrigated region), important parameters namely pH, electrical conductivity (EC), texture, bulk density (BD), saturated hydraulic conductivity (HC), soil organic carbon (OC), available water retension capacity (AWRC) and non capillary pores (NCP) were measured by collecting undisturbed soil samples in nearly 66 villages. Soil physical rating index (PI) method was used to compute PI which was an indicator of soil physical health of that region. Results revealed that in Gohana and Kharkhoda blocks, nearly 90% area had pH <8.0 and EC>4 dS m-1, which indicated that soils were saline. Prediction maps of soil BD showed that 75% of the total area in 15-30 cm soil layer had BD above >1.6 mg m -3, which indicated the presence of hard pan in subsurface. HC data of subsurface layer also showed that 60% of the area had values<0.5 cm hr -1 which reconfirmed the presence of hard pan. -

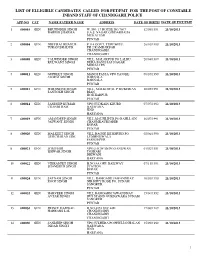

Seagate Crystal Reports

LIST OF ELLIGIBLE CANDIDATES CALLED FOR PET/PMT FOR THE POST OF CONSTABLE INBAND STAFF OF CHANDIGARH POLICE APP-NO CAT NAME FATHER NAME ADDRESS DATE OF BIRTH DATE OF PET/PMT 1 600003 GEN BHUPINDER SINGH W. NO. 17 HOUSE NO.7607 12/09/1991 21/10/2013 BABBHI SHARMA S.A.S. NAGAR GIDDARBAHA MUKATSAR PUNJAB 2 600004 GEN DHEERAJ BHADUR # 114 GOVT. TUBEWELL 26/10/1990 21/10/2013 PURAN BHADUR PH-2 RAMBARBAR CHANDIGARH CHANDIGARH 3 600008 GEN TALWINDER SINGH VILL. MALAKPUR PO LALRU 20/04/1989 21/10/2013 KULWANT SINGH DERA BASSI SAS NAGAR MOHALI PB PUNJAB 4 600011 GEN GUPREET SINGH MANDI PASSA VPO TAJOKE 08/10/1990 21/10/2013 JAGRAJ SINGH BARNALA BARNALA PUNJAB 5 600012 GEN HARJINDER SINGH VILL. MALKOWAL P MUKERIAN 10/05/1991 21/10/2013 SANTOKH SINGH RIAN HOSHIARPUR PUNJAB 6 600014 GEN SANDEEP KUMAR VPO SUDKAIN KHURD 07/07/1992 21/10/2013 CHANDI RAM NARWANA JIND HARYANA 7 600019 GEN AMANDEEP SINGH VILL.MAUJILIPUR PO BAHLLAIN 16/07/1991 21/10/2013 JASWANT SINGH CHANMKAURSAHIB ROPAR PUNJAB 8 600020 GEN MALKEET SINGH VILL.BAGGE KE KHURD PO 02/06/1990 21/10/2013 GURCHARAN SINGH LUMBERIWALA FEROZEPUR PUNJAB 9 600021 GEN SOMVERR VPO.SAGWAN PO.SANGWAN 01/02/1991 21/10/2013 ISHWAR SINGH TOSHAM BHIWANI HARYANA 10 600022 GEN VIKRAMJET SINGH H.NO.8A OPP. RAILWAY 07/11/1991 21/10/2013 SHAMSHER SINGH STATION ROPAR PUNJAB 11 600024 GEN SATNAM SINGH VILL. RAMGARH JAWANDHAY 10/03/1990 21/10/2013 ROOP SINGH NIR HIVY RODE PO. -

Final Sep-10 Project Status-Website

List of Ongoing Infrastructure projects in Haryana SubRegion with loan assistance from NCRPB(September 10) Original Date Loan Actual Loan Expenditure Implementing Date of Estimated cost S.No. Name of the Projects town of completion/ Sanctioned (Rs. Amount released reported (till Agency sanction (in Cr) revised date In Cr.) (till Sept 10) Sept 10) Haryana Sub Region Sewerage Sector Projects (22 nos.) Solid Waste Disposal & Repair of Roads in 16 Towns, Haryana Slum 1 Rohtak Mar-01 Mar-03 56.56 42.42 21.21 20.98 Haryana Clerance Board Municipal Revamping of Sewerage System and Sewage Treatment 2 Faridabad Corporation of Feb-07 Mar-10 103.83 23.36 17.52 77.2400 Works in Faridabad, Haryana Faridabad (MCF) 39.18 Developpgyment of Sewerage System and Construction of 3 Rohtak PHED Haryana Feb- 06 Feb09/Feb10Feb 09 / Feb 10 44. 25 33. 20 33. 20 two STPs at Rohtak town. 5.51 Providing sewerage system and STP for Samalkha 4 Samalkha PHED Haryana Feb-06 Feb 09 / Feb 10 8.10 6.08 1.22 Town, Haryana 7.35 5 Providing sewerage facilities in Palwal, Haryana Palwal PHED Haryana Feb-06 Feb 09 / Feb 10 9.76 7.32 4.39 9.63 Providing sewerage system for new colonies in Hodal 6 Hodal PHED Haryana Feb-06 Feb 09 / Feb 10 11.94 8.95 8.95 Town, Haryana Augmentation and Extension of Sewerage Scheme in 7 Sohna PHED Haryana Feb-06 Feb 09 / Feb 10 5.85 4.39 2.63 5.85 Sohna town, Haryana 12.56 8 Providing Sewerage facilities in Rewari Town, Haryana Rewari PHED Haryana Feb-06 Feb 09 / Feb 10 12.24 9.18 5.51 3.62 EEtxtensi on of fS Sewerage S yst em i n new col oni es -

List of Candidates Who Called for Interview on 27.2.12 from 10:00 AM

List of candidates who called for interview on 27.2.12 from 10:00 A.M. onwards for the post of Junior Store Keeper meant for UIET, M.D. University, Rohtak under Self Financing Scheme. Roll No Name, Father’s Name 101 RANBIR SINGH S/O SURAT SINGH, V.P.O-KHIDWALI, DISTT-OHTAK,HARYANA 102 RAMKARAN S/O RAMPHAL, V.P.O-KHIDWALI, DISTT-ROHTAK,HARYANA, PIN CODE- 124312 103 VIKASH S/O ROHTASH, V.P.O-KATHURA, TEH.-GOHANA,DISTT-SONIPAT, HARYANA- 131301 104 ASHOK KUMAR S/O OM PARKASH, H.NO-547/8, RAHMAN MANDI,ROHTAK, HARYANA-124001 105 GHANSHYAM S/O BHAGAT RAM, V.P.O-SUNDANA, TEH.-KALANOUR,DISTT- ROHTAK, HARYANA 106 KANCHAN CHHABRA D/O AMAR NATH C/O MR.VIKAS KHANIJO , H.NO-100/4, GALI NO-2, GURUCHARN PURA, NEAR OLD BUS STAND, ROHTAK 107 KAJAL KUMARI W/O SANJAY SHEORAN, H.NO-784/12, DEV COLONY, ROHTAK, HARYANA,124001 108 BHUPENDER SHARMA, S/O GANESH DUTT SHARMA,, H.NO-400A/22, KESHAV KUTEER, DURGA COLONY, ROHTAK 109 DINESH KUMAR S/O JEET SINGH, H.NO-2440, AMRIT COLONY, NEAR SHIV MANDIR,SUNARIAN CHOWK, RTK-124001 110 VIKAS S/O GULSHAN RAI, H.NO-19,W.NO-2, NEAR G.GR.SR.SEC.SCHOOL,KALANAUR, DISTT-ROHTAK-124113 111 ANUJ KAUSHIK S/O SATYA BHUSHAN KAUSHIK, HIRA CHOWK,BADHWANA GATE, CH.DADRI, DISTT-BHIWANI-127306 112 MOHAN SINGH S/O DHARA SINGH, H.NO-1350/30, SHRI NAGAR COLONY, ROHTAK 113 NUPUR D/o SH. Balwan SINGH C/O DHARAmPAL, H.NO-823/26,ATMA NAGAR,BHIWANI ROAD, JIND-126102 114 RANBIR SINGH S/O HUKAM SINGH, V.P.O-DIGHAL, PANA-MALAYAN, DISTT- JHAJJAR, PIN CODE-124107 115 SUNIL RATHEE S/O RAM KUMAR, V.P.O-NINDANA, TEH.-MEHAM, DISTT-ROHTAK. -

Frr\R'q Enqffeer-In-Chief, Dfuas Above Lrrigation and Water Resources Department, Haryana, Panchkula

"Eq {q tiqq, rq do q-4" Engineer-in-Chief, Irrigation & lluler Resources Department Panchkula, Haryana. e-muil:-@ Phone No.0172-2582541 No. O q /Drainage 11412021 Dated: 27.01.2021 To All the Members/Special lnvitees, Haryana State Drought Relief & Flood Control Board. (As per list attached). Subject: - Minutes of 52nd Meeting of Haryana State Drought Relief & Flood Gontrol Board. Kindly find enclosed herewith the Recommendations of SOth Meeting of HSTAC (Annexure-B) alongwith the minutes of 52nd Meeting of Haryana State Drought Relief & Flood Control Board held on 16.01.2021 under the Chairmanship of Hon'ble Ghief Minister, Haryana for information and necessary action. The minutes have been issued with the approval of the Hon'ble Chief Minister, Haryana and the same can also be downloaded from the official website " www.hid.gov. in." It is requested to send the action taken report on the points related to your office at the earliest. frr\r'q Enqffeer-in-Chief, DfuAs above lrrigation and Water Resources Department, Haryana, Panchkula. LIST OF MEMBERS HARYANA STATE DROUGHT RELIEF &FLOOD CONTROL BOARD OFFICIAL MEMBERS 1. Hon'ble Chief Minister, Haryana. Chairman 2. Irrigation and Water Resources Minister, Haryana. Vice Chairman 3. Finance Minister, Haryana. Member 4. Agriculture Minister, Haryana. -do- 5. Revenue & Disaster Management Minister, Haryana. -do- 6. Chief Secretary, Govt. of Haryana, Chandigarh. -do- 7. Additional Chief Secretary, Govt. of Haryana, -do- Revenue & Disaster Management Department, Chandigarh 8. Additional Chief Secretary, Govt. of Haryana, -do- PW (B&R) Department, Chandigarh. 9. Additional Chief Secretary, Government of Haryana, -do- Irrigation and Water Resources Department, Chandigarh. -

Officewise Postal Addresses of Public Health Engineering Deptt. Haryana

Officewise Postal Addresses of Public Health Engineering Deptt. Haryana Sr. Office Type Office Name Postal Address Email-ID Telephone No No. 1 Head Office Head Office Public Health Engineering Department, Bay No. 13 [email protected] 0172-2561672 -18, Sector 4, Panchkula, 134112, Haryana 2 Circle Ambala Circle 28, Park road, Ambala Cantt [email protected]. 0171-2601273 in 3 Division Ambala PHED 28, PARK ROAD,AMBALA CANTT. [email protected] 0171-2601208 4 Sub-Division Ambala Cantt. PHESD No. 2 28, PARK ROAD AMBALA CANTT. [email protected] 0171-2641062 5 Sub-Division Ambala Cantt. PHESD No. 4 28, PARK ROAD, AMBALA CANTT. [email protected] 0171-2633661 6 Sub-Division Ambala City PHESD No. 1 MODEL TOWN, AMBALA CITY [email protected] 0171-2601208 7 Division Ambala City PHED MODEL TOWN, AMBALA CITY NEAR SHARDA [email protected] 0171-2521121 RANJAN HOSPITAL OPP. PARK 8 Sub-Division Ambala City PHESD No. 3 MODEL TOWN, AMBALA CITY [email protected] 0171-2521121 9 Sub-Division Ambala City PHESD No. 5 MODEL TOWN, AMBALA CITY. [email protected] 0171-2521121 10 Sub-Division Ambala City PHESD No. 6 28, PARK ROAD, AMBALA CANTT. [email protected] 0171-2521121 11 Division Yamuna Nagar PHED No. 1 Executive engineer, Public health engineering [email protected] 01732-266050 division-1, behind Meat and fruit market, Industrial area Yamunanagar. 12 Sub-Division Chhachhrouli PHESD Near Community centre Chhachhrouli. [email protected] 01735276104 13 Sub-Division Jagadhri PHESD No.