Revisioning Europe: the Films of John Berger and Alain Tanner

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Broadcasting Taste: a History of Film Talk, International Criticism, and English-Canadian Media a Thesis in the Department of Co

Broadcasting Taste: A History of Film Talk, International Criticism, and English-Canadian Media A Thesis In the Department of Communication Studies Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Communication Studies) at Concordia University Montreal, Quebec, Canada December 2016 © Zoë Constantinides, 2016 CONCORDIA UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES This is to certify that the thesis prepared By: Zoë Constantinides Entitled: Broadcasting Taste: A History of Film Talk, International Criticism, and English- Canadian Media and submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of PhD in Communication Studies complies with the regulations of the University and meets the accepted standards with respect to originality and quality. Signed by the final examining committee: __________________________________________ Beverly Best Chair __________________________________________ Peter Urquhart External Examiner __________________________________________ Haidee Wasson External to Program __________________________________________ Monika Kin Gagnon Examiner __________________________________________ William Buxton Examiner __________________________________________ Charles R. Acland Thesis Supervisor Approved by __________________________________________ Yasmin Jiwani Graduate Program Director __________________________________________ André Roy Dean of Faculty Abstract Broadcasting Taste: A History of Film Talk, International Criticism, and English- Canadian Media Zoë Constantinides, -

The Inventory of the Richard Roud Collection #1117

The Inventory of the Richard Roud Collection #1117 Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center ROOD, RICHARD #1117 September 1989 - June 1997 Biography: Richard Roud ( 1929-1989), as director of both the New York and London Film Festivals, was responsible for both discovering and introducing to a wider audience many of the important directors of the latter half th of the 20 - century (many of whom he knew personally) including Bernardo Bertolucci, Robert Bresson, Luis Buiiuel, R.W. Fassbinder, Jean-Luc Godard, Werner Herzog, Terry Malick, Ermanno Ohni, Jacques Rivette and Martin Scorsese. He was an author of books on Jean-Marie Straub, Jean-Luc Godard, Max Ophuls, and Henri Langlois, as well as the editor of CINEMA: A CRITICAL DICTIONARY. In addition, Mr. Roud wrote extensive criticism on film, the theater and other visual arts for The Manchester Guardian and Sight and Sound and was an occasional contributor to many other publications. At his death he was working on an authorized biography of Fran9ois Truffaut and a book on New Wave film. Richard Roud was a Fulbright recipient and a Chevalier in the Legion of Honor. Scope and contents: The Roud Collection (9 Paige boxes, 2 Manuscript boxes and 3 Packages) consists primarily of book research, articles by RR and printed matter related to the New York Film Festival and prominent directors. Material on Jean-Luc Godard, Francois Truffaut and Henri Langlois is particularly extensive. Though considerably smaller, the Correspondence file contains personal letters from many important directors (see List ofNotable Correspondents). The Photographs file contains an eclectic group of movie stills. -

NATIONAL FILM BOARD of CANADA FEATURED at Moma

The Museum off Modern Art 50th Anniversary NO. 16 ID FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE March 3, 1981 DOCUMENTARY FILMS FROM THE NATIONAL FILM BOARD OF CANADA FEATURED AT MoMA NATIONAL FILM BOARD OF CANADA: A RETROSPECTIVE is a three-part tribute presented by The Museum of Modern Art in recog nition of NFBC's 41 years Of exceptional filmmaking. PART TWO: DOCUMENTARY FILMS, running from March 26 through May 12 in the Museum's Roy and Niuta Titus Auditorium, will trace the develop ment of the documentary form at NFBC, and will be highlighted by a selection of some of the finest films directed by Donald Brittain, whose work has won wide acclaim and numerous awards. PART TWO: DOCUMENTARY will get off to an auspicious start with twelve of Donald Brittain's powerful and unconventional portraits of exceptional individuals. Best known in this country for "Volcano: An Inquiry Into The Life and Death of Malcolm Lowry" (1976), Brittain brings his personal stamp of creative interpretation to such subjects as America's love affair with the automobile in "Henry Ford's America" (1976) ; the flamboyant Lord Thompson of Fleet Street (the newspaper baron who just sold the cornerstone of his empire, The London Times) in "Never A Backward Step" (1966); Norman Bethune, the Canadian poet/ doctor/revolutionary who became a great hero in China when he marched with Mao ("Bethune" 1964); and the phenomenal media hysteria sur rounding the famous quintuplets in "The Diorme Years" (1979) . "Memo randum" (1965) accompanies a Jewish glazier from Tcronto when he takes his son back to the concentration camp where he was interned, an emotion al and historical pilgrimage of strong impact and sensitivity. -

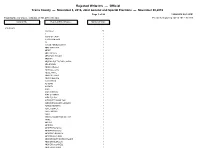

Rejected Write-Ins

Rejected Write-Ins — Official Travis County — November 8, 2016, Joint General and Special Elections — November 08,2016 Page 1 of 28 12/08/2016 02:12 PM Total Number of Voters : 496,044 of 761,470 = 65.14% Precincts Reporting 247 of 268 = 92.16% Contest Title Rejected Write-In Names Number of Votes PRESIDENT <no name> 58 A 2 A BAG OF CRAP 1 A GIANT METEOR 1 AA 1 AARON ABRIEL MORRIS 1 ABBY MANICCIA 1 ABDEF 1 ABE LINCOLN 3 ABRAHAM LINCOLN 3 ABSTAIN 3 ABSTAIN DUE TO BAD CANDIA 1 ADA BROWN 1 ADAM CAROLLA 2 ADAM LEE CATE 1 ADELE WHITE 1 ADOLPH HITLER 2 ADRIAN BELTRE 1 AJANI WHITE 1 AL GORE 1 AL SMITH 1 ALAN 1 ALAN CARSON 1 ALEX OLIVARES 1 ALEX PULIDO 1 ALEXANDER HAMILTON 1 ALEXANDRA BLAKE GILMOUR 1 ALFRED NEWMAN 1 ALICE COOPER 1 ALICE IWINSKI 1 ALIEN 1 AMERICA DESERVES BETTER 1 AMINE 1 AMY IVY 1 ANDREW 1 ANDREW BASAIGO 1 ANDREW BASIAGO 1 ANDREW D BASIAGO 1 ANDREW JACKSON 1 ANDREW MARTIN ERIK BROOKS 1 ANDREW MCMULLIN 1 ANDREW OCONNELL 1 ANDREW W HAMPF 1 Rejected Write-Ins — Official Travis County — November 8, 2016, Joint General and Special Elections — November 08,2016 Page 2 of 28 12/08/2016 02:12 PM Total Number of Voters : 496,044 of 761,470 = 65.14% Precincts Reporting 247 of 268 = 92.16% Contest Title Rejected Write-In Names Number of Votes PRESIDENT Continued.. ANN WU 1 ANNA 1 ANNEMARIE 1 ANONOMOUS 1 ANONYMAS 1 ANONYMOS 1 ANONYMOUS 1 ANTHONY AMATO 1 ANTONIO FIERROS 1 ANYONE ELSE 7 ARI SHAFFIR 1 ARNOLD WEISS 1 ASHLEY MCNEILL 2 ASIKILIZAYE 1 AUSTIN PETERSEN 1 AUSTIN PETERSON 1 AZIZI WESTMILLER 1 B SANDERS 2 BABA BOOEY 1 BARACK OBAMA 5 BARAK -

Alain Tanner Филм ÑÐ ¿Ð¸ÑÑ ŠÐº (ФилмографиÑ)

Alain Tanner Филм ÑÐ ¿Ð¸ÑÑ ŠÐº (ФилмографиÑ) Light Years Away https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/light-years-away-1402542/actors The Woman from Rose Hill https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-woman-from-rose-hill-18542955/actors The Diary of Lady M https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-diary-of-lady-m-18604474/actors https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/la-vall%C3%A9e-fant%C3%B4me- La vallée fantôme 21647262/actors The Man Who Lost His Shadow https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-man-who-lost-his-shadow-24938017/actors A Flame in My Heart https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/a-flame-in-my-heart-27666257/actors The Salamander https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-salamander-3212693/actors The Middle of the World https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-middle-of-the-world-3224550/actors No Man's Land https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/no-man%27s-land-3342426/actors Nice Time https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/nice-time-3382446/actors Charles, Dead or Alive https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/charles%2C-dead-or-alive-384776/actors Fleurs de sang https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/fleurs-de-sang-48746792/actors Les hommes du port https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/les-hommes-du-port-50184103/actors Messidor https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/messidor-512192/actors Fourbi https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/fourbi-5475762/actors Requiem https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/requiem-56306217/actors The Apprentices https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-apprentices-64732218/actors Jonah Who Will Be 25 in the Year https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/jonah-who-will-be-25-in-the-year-2000- 2000 670633/actors In the White City https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/in-the-white-city-679684/actors Rousseau chez Alain Tanner https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/rousseau-chez-alain-tanner-90159411/actors. -

Film Reference Guide

REFERENCE GUIDE THIS LIST IS FOR YOUR REFERENCE ONLY. WE CANNOT PROVIDE DVDs OF THESE FILMS, AS THEY ARE NOT PART OF OUR OFFICIAL PROGRAMME. HOWEVER, WE HOPE YOU’LL EXPLORE THESE PAGES AND CHECK THEM OUT ON YOUR OWN. DRAMA 1:54 AVOIR 16 ANS / TO BE SIXTEEN 2016 / Director-Writer: Yan England / 106 min / 1979 / Director: Jean Pierre Lefebvre / Writers: Claude French / 14A Paquette, Jean Pierre Lefebvre / 125 min / French / NR Tim (Antoine Olivier Pilon) is a smart and athletic 16-year- An austere and moving study of youthful dissent and old dealing with personal tragedy and a school bully in this institutional repression told from the point of view of a honest coming-of-age sports movie from actor-turned- rebellious 16-year-old (Yves Benoît). filmmaker England. Also starring Sophie Nélisse. BACKROADS (BEARWALKER) 1:54 ACROSS THE LINE 2000 / Director-Writer: Shirley Cheechoo / 83 min / 2016 / Director: Director X / Writer: Floyd Kane / 87 min / English / NR English / 14A On a fictional Canadian reserve, a mysterious evil known as A hockey player in Atlantic Canada considers going pro, but “the Bearwalker” begins stalking the community. Meanwhile, the colour of his skin and the racial strife in his community police prejudice and racial injustice strike fear in the hearts become a sticking point for his hopes and dreams. Starring of four sisters. Stephan James, Sarah Jeffery and Shamier Anderson. BEEBA BOYS ACT OF THE HEART 2015 / Director-Writer: Deepa Mehta / 103 min / 1970 / Director-Writer: Paul Almond / 103 min / English / 14A English / PG Gang violence and a maelstrom of crime rock Vancouver ADORATION A deeply religious woman’s piety is tested when a in this flashy, dangerous thriller about the Indo-Canadian charismatic Augustinian monk becomes the guest underworld. -

General Election November 8, 2016

GENERAL ELECTION NOVEMBER 8, 2016 Pursuant to the General Election Warning recorded in the Town Records, Book 20, pages 432, the polls were declared open at 7:00A.M. by the Town Clerk in the three polling districts. The three polling districts are stated in the Warning. At 6:55 P.M. the Town Clerk warned that the polls would close in 5 minutes. At 7:00 P.M. the polls were declared closed. Printouts from each of the Accu-Vote ballot tabulators used to record results of the election were run. The “unofficial” returns were then posted at the polling places. Result summaries were compiled by the Town Clerk and evening election workers. Upon completion of the count, all voted ballots were sealed in boxes. All unvoted ballots, tabulators with program cards, printouts, tally sheets and district supply boxes were returned to the Town Clerk’s office. The “official” results were compiled and the following persons were declared elected in their respective races. OFFICIAL RETURN OF VOTES US President District 1 District 2 District 3 TOTAL Hillary Clinton 1489 1367 1491 4347 Rocky De La Fuente 5 3 1 9 Gary Johnson 31 32 32 95 Gloria Lariva 1 4 1 6 Jill Stein 51 110 75 236 Donald J. Trump 425 216 217 858 Write-ins: Names Votes per write-in Bernie Sanders 344 John Kasich, John McCain, Evan McMullen 4 Mitt Romney 3 Paul Ryan, Evan McMullin, Michael Pence, Ted Cruz, 2 Darrel Castle, Jeb Bush Cherie Vickery, Elan Musk, John Huntsman Jr, Joe Biden, Jerry White, Josh Doubleday, Alex Johnson, Ben Carson, Phil Zorian Ron Paul, 1 Steven Tyler, Vermin Supreme, Tim Kaine, Tom Castano US Senator District 1 District 2 District 3 TOTAL Pete Diamondstone 61 99 83 243 Cris Ericson 64 79 75 218 Patrick Leahy 1517 1387 1442 4346 Scott Milne 422 207 244 873 Jerry Trudell 43 52 31 126 Write-ins: Bernie Sanders, 2; Riley Goodemote, 1; Saunders, 1. -

Miroir Du Cinéma, N° 2 (Mai 1962) Exclusif : Entretiens Avec Marker - Gatti

Miroir du Cinéma, n° 2 (mai 1962) Exclusif : entretiens avec Marker - Gatti Ils sont dignes d’être aimés (p. 1) Si errant les yeux grands ouvert au mitan d’une ruelle pavée de mauvaises intentions et peuplée des cauchemars d’un millier de bourgeois, je découvrais devant moi le dos de Marker sur le trottoir de droite et le dos de Gatti sur le trottoir de gauche (ou vice-versa, n’abusons pas), je ne m’étonnerais pas. Ces deux-là hantent tous les lieux, même abandonnés du diable, pourvu que l’on y croise des hommes. C’est peut-être Marker alors que je tenterais de joindre le premier... ou peut-être Gatti, ou plutôt, je gueulerais « à l’assassin », tel Roland. Car tous deux, en ces temps où il est plus prudent de gueuler « au feu » pour être secouru ; sont de ceux, rares qui assument toutes les victimes, de préférence avant qu’elles ne soient mortes. L’une, c’est le feu, l’autre, la flamme. Feu, froid ou flamme sombre, qu’importe pourvu que cela brûle... L’un dit « couilles », l’autre choisit ses mots, l’un c’est la coiffure-tempête, l’autre des yeux de chat, l’un les bégaiements de la violence, l’autre un saxo à peine ouvert, l’un des mains de bûcheron, l’autre un crâne bien astiqué... l’un est écorché à vif sous ses masques, l’autre déballe à la première connivence, l’un fait le hérisson, l’autre à toujours les tripes à l’air, l’un descend d’un balayeur antifasciste, l’autre d’une fausse légende viking.. -

Redirected from Films Considered the Greatest Ever) Page Semi-Protected This List Needs Additional Citations for Verification

List of films considered the best From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia (Redirected from Films considered the greatest ever) Page semi-protected This list needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be chall enged and removed. (November 2008) While there is no general agreement upon the greatest film, many publications an d organizations have tried to determine the films considered the best. Each film listed here has been mentioned in a notable survey, whether a popular poll, or a poll among film reviewers. Many of these sources focus on American films or we re polls of English-speaking film-goers, but those considered the greatest withi n their respective countries are also included here. Many films are widely consi dered among the best ever made, whether they appear at number one on each list o r not. For example, many believe that Orson Welles' Citizen Kane is the best mov ie ever made, and it appears as #1 on AFI's Best Movies list, whereas The Shawsh ank Redemption is #1 on the IMDB Top 250, whilst Star Wars Episode V: The Empire Strikes Back is #1 on the Empire magazine's Top 301 List. None of the surveys that produced these citations should be viewed as a scientif ic measure of the film-watching world. Each may suffer the effects of vote stack ing or skewed demographics. Internet-based surveys have a self-selected audience of unknown participants. The methodology of some surveys may be questionable. S ometimes (as in the case of the American Film Institute) voters were asked to se lect films from a limited list of entries. -

List of Films Considered the Best

Create account Log in Article Talk Read View source View history Search List of films considered the best From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Main page This list needs additional citations for verification. Please Contents help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Featured content Current events Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (November Random article 2008) Donate to Wikipedia Wikimedia Shop While there is no general agreement upon the greatest film, many publications and organizations have tried to determine the films considered the best. Each film listed here has been mentioned Interaction in a notable survey, whether a popular poll, or a poll among film reviewers. Many of these sources Help About Wikipedia focus on American films or were polls of English-speaking film-goers, but those considered the Community portal greatest within their respective countries are also included here. Many films are widely considered Recent changes among the best ever made, whether they appear at number one on each list or not. For example, Contact page many believe that Orson Welles' Citizen Kane is the best movie ever made, and it appears as #1 Tools on AFI's Best Movies list, whereas The Shawshank Redemption is #1 on the IMDB Top 250, whilst What links here Star Wars Episode V: The Empire Strikes Back is #1 on the Empire magazine's Top 301 List. Related changes None of the surveys that produced these citations should be viewed as a scientific measure of the Upload file Special pages film-watching world. Each may suffer the effects of vote stacking or skewed demographics. -

111714906.Pdf

1 4 Films by Alain Tanner Screening at the Wooden Shoe, 704 South St., Philadelphia. Zine published in collaboration with Shooting Wall. Friday November 2 7PM La Salamandre (The Salamander) 1971 124min. Starring Bulle Ogier, Jean-Luc Bideau, & Jacques Denis Saturday November 3 7 PM Le Milieu du monde (The Middle of the World ) 1974 115min. Starring Olimpia Carlisi, Philippe Léotard, & Juliet Berto Friday November 9 7 PM Jonas qui aura 25 ans en l'an 2000 (Jonah Who Will Be 25 in the Year 2000) 1976 116min. Starring Jean-Luc Bideau, Myriam Boyer, Raymond Bussiéres, Jacques Denis, Roger Jendly, Dominique Labourier, Myriam Mé- ziéres, Miou-Miou, Rufus Saturday November 10 7PM Messidor 1979 123min. Starring Clémentine Amouroux & Catherine Rétouré Contents About Alain Tanner & Resources 3 A Long Introduction 4 Ben Webster Le Milieu du monde 16 Ross Wilbanks Investigating Reality: Character, Idealism, & 19 Political Ideology in Alain Tanner‟s La Salamandre Josh Martin Don‟t Fuck the Boss! 22 Ben Webster 2 About Alain Tanner (courtesy Wikipedia) Alain Tanner (born 6 December 1929, Geneva) is a Swiss film director. Tanner found work at the British Film Institute in 1955, subtitling, translating, and organizing the archive. His first film, Nice Time (1957), a short documen- tary film about Piccadilly Circus during weekend evenings, was made with Claude Goretta. Produced by the British Film Institute Experimental Film Fund, it was first shown as part of the third Free Cinema programme at the Na- tional Film Theatre in May 1957. The debut film won a prize at the film festival in Venice and much critical praise. -

The Regents of the University of California, Berkeley – UC Berkeley Art Museum & Pacific Film Archive (BAMPFA)

Recordings at Risk Sample Proposal (Fourth Call) Applicant: The Regents of the University of California, Berkeley – UC Berkeley Art Museum & Pacific Film Archive (BAMPFA) Project: Saving Film Exhibition History: Digitizing Recordings of Guest Speakers at the Pacific Film Archive, 1976 to 1986 Portions of this successful proposal have been provided for the benefit of future Recordings at Risk applicants. Members of CLIR’s independent review panel were particularly impressed by these aspects of the proposal: • The broad scholarly and public appeal of the included filmmakers; • Well-articulated statements of significance and impact; • Strong letters of support from scholars; and, • A plan to interpret rights in a way to maximize access. Please direct any questions to program staff at [email protected] Application: 0000000148 Recordings at Risk Summary ID: 0000000148 Last submitted: Jun 28 2018 05:14 PM (EDT) Application Form Completed - Jun 28 2018 Form for "Application Form" Section 1: Project Summary Applicant Institution (Legal Name) The Regents of the University of California, Berkeley Applicant Institution (Colloquial Name) UC Berkeley Art Museum & Pacific Film Archive (BAMPFA) Project Title (max. 50 words) Saving Film Exhibition History: Digitizing Recordings of Guest Speakers at the Pacific Film Archive, 1976 to 1986 Project Summary (max. 150 words) In conjunction with its world-renowned film exhibition program established in 1971, the UC Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive (BAMPFA) began regularly recording guest speakers in its film theater in 1976. The first ten years of these recordings (1976-86) document what has become a hallmark of BAMPFA’s programming: in-person presentations by acclaimed directors, including luminaries of global cinema, groundbreaking independent filmmakers, documentarians, avant-garde artists, and leaders in academic and popular film criticism.