Notes from My Psychosis--Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Radiohead's Pre-Release Strategy for in Rainbows

Making Money by Giving It for Free: Radiohead’s Pre-Release Strategy for In Rainbows Faculty Research Working Paper Series Marc Bourreau Telecom ParisTech and CREST Pinar Dogan Harvard Kennedy School Sounman Hong Yonsei University July 2014 RWP14-032 Visit the HKS Faculty Research Working Paper Series at: http://web.hks.harvard.edu/publications The views expressed in the HKS Faculty Research Working Paper Series are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of the John F. Kennedy School of Government or of Harvard University. Faculty Research Working Papers have not undergone formal review and approval. Such papers are included in this series to elicit feedback and to encourage debate on important public policy challenges. Copyright belongs to the author(s). Papers may be downloaded for personal use only. www.hks.harvard.edu Makingmoneybygivingitforfree: Radiohead’s pre-release strategy for In Rainbows∗ Marc Bourreau†,Pınar Dogan˘ ‡, and Sounman Hong§ June 2014 Abstract In 2007 a prominent British alternative-rock band, Radiohead, pre-released its album In Rainbows online, and asked their fans to "pick-their-own-price" (PYOP) for the digital down- load. The offer was available for three months, after which the band released and commercialized the album, both digitally and in CD. In this paper, we use weekly music sales data in the US between 2004-2012 to examine the effect of Radiohead’s unorthodox strategy on the band’s al- bum sales. We find that Radiohead’s PYOP offer had no effect on the subsequent CD sales. Interestingly, it yielded higher digital album sales compared to a traditional release. -

P28 Layout 1

28 Established 1961 Lifestyle Gossip Wednesday, December 13, 2017 Lily Allen Cabello praises drops first song artists for in three years ‘breaking barriers’ he ‘Smile’ hitmaker hasn’t put out any tunes since her album ‘Sheezus’, but surprised fans on Monday night, by dropping amila Cabello thinks there is a lot of “breaking barriers” in the coming-of-age banger about her wild past. On the track, the music industry right now. The ‘Havana’ hitmaker is thrilled T to see Latin artists getting mainstream recognition now and she sings: “When I was young I was blameless/ Playing with rude C boys and trainers/ I had a foot in the rave ‘cause I was attracted to thinks there has been a big shift in the industry. She said: “I think danger/ I never got home for Neighbors, hey/ When I grew up, noth- that the good thing about social media and the internet is that I feel ing changed much/ Anything went, I was famous /I would wake up like it makes the world smaller and it just kind of breaks down barri- next to strangers/ Everyone knows what cocaine does/ Numbing the ers between languages, between people, between cultures, and I pain when the shame comes, hey (sic)” In October last year, Lily think that might have something to do with that. I’ve been listening debuted a new track at Mark Ronson’s show at The Savoy hotel in to Spanish music forever because that’s just not even Spanish music London. The ‘Alfie’ hitmaker took to the stage to perform three songs to me, it’s just music “But I feel like with everything that’s gone on at the MasterCard Priceless event, including a brand new electronic this year and also with groups like K-pop groups performing on dance track which she created with the superstar DJ. -

Tom Odell Releases New Album Wrong Crowd Today, Friday June 10 on Rca Records, the Follow up to His Million-Selling Debut Long Way Down

TOM ODELL RELEASES NEW ALBUM WRONG CROWD TODAY, FRIDAY JUNE 10 ON RCA RECORDS, THE FOLLOW UP TO HIS MILLION-SELLING DEBUT LONG WAY DOWN VIDEOS FOR TITLE TRACK “WRONG CROWD,” LEAD SINGLE “MAGNETISED”,”SOMEHOW” AND “CONCRETE” AVALABLE NOW- CLICK HERE TO WATCH (New York - June 10, 2016) Tom Odell releases his second album WRONG CROWD today, Friday 10 June. WRONG CROWD is the follow up his 2013’s million selling, #1 UK debuting album Long Way Down. Long Way Down, his debut album was met with tremendous critical reaction and earned him the highly prestigious Ivor Novello Award for Songwriter of the Year and the Brits Critics’ Choice Award. Tom will be performing his current single “Magnetised” on “The Today Show” on June 29th. Click here to watch his performance on “The Tonight Show Starring Jimmy Fallon” and watch his performance and chat on “The Late Late Show with James Corden.” People Magazine declared that Odell “solidifies his sound” on WRONG CROWD, Wall Street Journal described him as “soulful” and Q Magazine calls “’Magnetized’(is) thrillingly melodic.” WRONG CROWD consists of 11 songs and 4 bonus tracks. The videos for “Wrong Crowd,” and “Magnetised” were shot in South Africa, and directed by George Belfield (Arthur Beatrice, Richard Hawley, Kwabs). The storyline for the “Magnetised” video is a continuation of the “Wrong Crowd” video which also includes a portion of the song “Constellations.” Tom recently performed a slew of underplay shows in Europe, New York and Los Angeles to rave response. The UK Telegraph wrote of his London show that Odell was “electrifying…with a big, bold, bravura performance … a whole layer of charismatic rock swagger…Odell might be the missing link between showboating Seventies Elton and the epic emotionalism of Coldplay. -

Some New Music to Turn That Frown Upside-Down

Some New Music To Turn That Frown Upside-Down Bittle Magazine | Record Reviews This June has been something of a short, hard kick in the face for all those who say there is no good new music out there, with so many great new albums that it‘s hard to know where to begin. By JOHN BITTLES. Seriously, it’s almost as if those within the music business knew about my spiralling DJ Sprinkles addiction and decided to release lots of great music to help wean me off. We have the gorgeous romantic house vibes of Glitterbug, the melancholy soul-searching of The Antlers, synth-pop gold from Lust For Youth, killer slacker rock from Happyness and so much more. And if you still aren’t excited about new music after reading this article then just play ›Midtown 120 Blues‹ on repeat. It works for me! This month we’re gonna start with one of the most surprisingly touching and exciting new albums of the last few weeks, ›Weird Little Birthday‹ , the debut album by London-based newcomers Happyness. Taking US slacker rock as a starting point the band give us 13 tracks that are, at turns, tear inducing, bittersweet, and full of that ‘We don’t give a fuck’ attitude that you’ve just got to love. ›Naked Patients‹ , the album’s second track has already been proven by a top team of scientists (me and my mate Steve) to increase a listeners ‘hip’ quota by 15 whole points! Meanwhile ›Orange Luz‹ is so laidback it almost forgets it’s there. -

2017 MAJOR EURO Music Festival CALENDAR Sziget Festival / MTI Via AP Balazs Mohai

2017 MAJOR EURO Music Festival CALENDAR Sziget Festival / MTI via AP Balazs Mohai Sziget Festival March 26-April 2 Horizon Festival Arinsal, Andorra Web www.horizonfestival.net Artists Floating Points, Motor City Drum Ensemble, Ben UFO, Oneman, Kink, Mala, AJ Tracey, Midland, Craig Charles, Romare, Mumdance, Yussef Kamaal, OM Unit, Riot Jazz, Icicle, Jasper James, Josey Rebelle, Dan Shake, Avalon Emerson, Rockwell, Channel One, Hybrid Minds, Jam Baxter, Technimatic, Cooly G, Courtesy, Eva Lazarus, Marc Pinol, DJ Fra, Guim Lebowski, Scott Garcia, OR:LA, EL-B, Moony, Wayward, Nick Nikolov, Jamie Rodigan, Bahia Haze, Emerald, Sammy B-Side, Etch, Visionobi, Kristy Harper, Joe Raygun, Itoa, Paul Roca, Sekev, Egres, Ghostchant, Boyson, Hampton, Jess Farley, G-Ha, Pixel82, Night Swimmers, Forbes, Charline, Scar Duggy, Mold Me With Joy, Eric Small, Christer Anderson, Carina Helen, Exswitch, Seamus, Bulu, Ikarus, Rodri Pan, Frnch, DB, Bigman Japan, Crawford, Dephex, 1Thirty, Denzel, Sticky Bandit, Kinno, Tenbagg, My Mate From College, Mr Miyagi, SLB Solden, Austria June 9-July 10 DJ Snare, Ambiont, DLR, Doc Scott, Bailey, Doree, Shifty, Dorian, Skore, March 27-April 2 Web www.electric-mountain-festival.com Jazz Fest Vienna Dossa & Locuzzed, Eksman, Emperor, Artists Nervo, Quintino, Michael Feiner, Full Metal Mountain EMX, Elize, Ernestor, Wastenoize, Etherwood, Askery, Rudy & Shany, AfroJack, Bassjackers, Vienna, Austria Hemagor, Austria F4TR4XX, Rapture,Fava, Fred V & Grafix, Ostblockschlampen, Rafitez Web www.jazzfest.wien Frederic Robinson, -

Uk Versus Usa at the Shockwaves Nme Awards 2007

STRICTLY EMBARGOED UNTIL 8PM MONDAY 29 TH JANUARY Insert logo UK VERSUS USA AT THE SHOCKWAVES NME AWARDS 2007 Expect blood, sweat and tears as we prepare for what will undoubtedly be one big dirty rock’n’roll battle of the bands – and of the nations – at the Shockwaves NME Awards 2007 . The best of British – Arctic Monkeys , Muse and Kasabian – will take on stateside success stories My Chemical Romance and The Killers on March 1 at Hammersmith Palais. Let battle commence! This year, there’s no one clear leader but FIVE bands that dominate the nominations list. With four nominations each, Arctic Monkeys, Muse, Kasabian, The Killers and My Chemical Romance have been chosen by the fans to fight it out on the night. For the past two years, it’s been British bands sweeping the board, but this year The Killers and My Chemical Romance may very well make the 2007 ceremony a stateside success story. Arctic Monkeys made NME Awards history last year by scooping the Award for both Best New Band and Best British Band in the same year, in addition to winning Best Track and scoring a nomination for Best Live Band . Sheffield’s favourites have matched their achievement, with four nominations this year for Best British Band, Best Live Band, Best Album and Best Music DVD. Arctic Monkeys said: “Very nice, we didn’t think we would get any this year! It seems weird for us to be alongside them [the competition] because we still feel like a little band. When it’s your own thing you don’t really see yourself alongside The Killers and Kasabian.” The Monkeys have more than one tough fight on their hands if they want to claim the Best British Band title for the second year running, though. -

Album Top 1000 2021

2021 2020 ARTIEST ALBUM JAAR ? 9 Arc%c Monkeys Whatever People Say I Am, That's What I'm Not 2006 ? 12 Editors An end has a start 2007 ? 5 Metallica Metallica (The Black Album) 1991 ? 4 Muse Origin of Symmetry 2001 ? 2 Nirvana Nevermind 1992 ? 7 Oasis (What's the Story) Morning Glory? 1995 ? 1 Pearl Jam Ten 1992 ? 6 Queens Of The Stone Age Songs for the Deaf 2002 ? 3 Radiohead OK Computer 1997 ? 8 Rage Against The Machine Rage Against The Machine 1993 11 10 Green Day Dookie 1995 12 17 R.E.M. Automa%c for the People 1992 13 13 Linkin' Park Hybrid Theory 2001 14 19 Pink floyd Dark side of the moon 1973 15 11 System of a Down Toxicity 2001 16 15 Red Hot Chili Peppers Californica%on 2000 17 18 Smashing Pumpkins Mellon Collie and the Infinite Sadness 1995 18 28 U2 The Joshua Tree 1987 19 23 Rammstein Muaer 2001 20 22 Live Throwing Copper 1995 21 27 The Black Keys El Camino 2012 22 25 Soundgarden Superunknown 1994 23 26 Guns N' Roses Appe%te for Destruc%on 1989 24 20 Muse Black Holes and Revela%ons 2006 25 46 Alanis Morisseae Jagged Liale Pill 1996 26 21 Metallica Master of Puppets 1986 27 34 The Killers Hot Fuss 2004 28 16 Foo Fighters The Colour and the Shape 1997 29 14 Alice in Chains Dirt 1992 30 42 Arc%c Monkeys AM 2014 31 29 Tool Aenima 1996 32 32 Nirvana MTV Unplugged in New York 1994 33 31 Johan Pergola 2001 34 37 Joy Division Unknown Pleasures 1979 35 36 Green Day American idiot 2005 36 58 Arcade Fire Funeral 2005 37 43 Jeff Buckley Grace 1994 38 41 Eddie Vedder Into the Wild 2007 39 54 Audioslave Audioslave 2002 40 35 The Beatles Sgt. -

KEY SONGS and We’Ll Tell Everyone Else

Cover-15.03.13_cover template 12/03/13 09:49 Page 1 11 9 776669 776136 THE BUSINESS OF MUSIC www.musicweek.com 15.03.13 £5.15 40 million albums sold worldwide 8 million albums sold in the UK Project1_Layout 1 12/03/2013 10:07 Page 1 Multiple Grammy Award winner to release sixth studio album ahead of his ten sold out dates in June at the O2 Arena ‘To Be Loved’ 15/04/2013 ‘It’s A Beautiful Day’ 08/04/2013 Radio Added to Heart, Radio 2, Magic, Smooth, Real, BBC Locals Highest New Entry and Highest Mover in Airplay Number 6 in Airplay Chart TV March BBC Breakfast Video Exclusive 25/03 ‘It’s A Beautiful Day’ Video In Rotation 30/03 Ant & Dec Saturday Night Takeaway 12/04 Graham Norton Interview And Performance June 1 Hour ITV Special Expected TV Audience of 16 million, with further TVs to be announced Press Covers and features across the national press Online Over 5.5 million likes on Facebook Over 1 million followers on Twitter Over 250 million views on YouTube Live 10 Consecutive Dates At London’s O2 Arena 30th June • 1st July • 3rd July • 4th July 5thSOLD July OUT • 7thSOLD July OUT • 8thSOLD July OUT • 10thSOLD July OUT 12thSOLD July OUT • 13thSOLD July OUT SOLD OUT SOLD OUT SOLD OUT SOLD OUT Marketing Nationwide Poster Campaign Nationwide TV Advertising Campaign www.michaelbuble.com 01 MARCH15 Cover_v5_cover template 12/03/13 13:51 Page 1 11 9 776669 776136 THE BUSINESS OF MUSIC www.musicweek.com 15.03.13 £5.15 ANALYSIS PROFILE FEATURE 12 15 18 The story of physical and digital Music Week talks to the team How the US genre is entertainment retail in 2012, behind much-loved Sheffield crossing borders ahead of with new figures from ERA venue The Leadmill London’s C2C festival Pet Shop Boys leave Parlophone NEW ALBUM COMING IN JUNE G WORLDWIDE DEAL SIGNED WITH KOBALT LABEL SERVICES TALENT can say they have worked with I BY TIM INGHAM any artist for 28 years, but Parlophone have and we are very et Shop Boys have left proud of that. -

Demented Lullaby British: Queens of the Stone Age on the Follow-Up to 2002'S Breakthrough Ing the Catchy Beating of a Cowbell

·arcade Demented lullaby British: Queens of the Stone Age on the follow-up to 2002's breakthrough ing the catchy beating of a cowbell. they're Lullabies to Paralyze Songs for the Deaf, lending a hand to The album as a whole slithers its way QOTSA co-founder Josh Homme. toward a more eerie and nocturnal feel lnt****erscope Records* The CD inlay, decorated with goat with each song ending with a psyche- • rock heads and pentagrams, echoes the delic hidden track, like waking up from daunting, lurid mood of Lullabies to a bizarre nightmare. coming Kevin Yeh Paralyze. Certain songs really grab the While the band's signature sound Kasabian reviews editor listener by the horns. The sharp riffs in qualities were present on this album, "Someone's in the Wolf' dotted with QOTSA should not shy away from that Self-titled With the departure of bassist Nick strange laughing and creepy hissing creepy and haunting sound as much as epitomize the album. The tiptoeing of they did. They give the curious listeners **RCA ***Records Oliveri, Queens of the Stone Age releas- brit-pop es its fifth album filled with spooks, the piano in "Tangled up in Plaid" and a small peek into the world of ghoulish haunts and cowbells. The loss of a the heavy breathing that introduces the dreams, leaving them craving more. Michael Drohan bassist, however, does not equal a loss in spine-chilling harmonies of "Burn the staff writer quality. The band comes through using a Witch" crystallize the chilling sound Bottom Line: Queens of the Stone variety of instruments that provide for QOTSA is aiming for. -

Franz Ferdinand Tell Her Tonight Download

Franz ferdinand tell her tonight download Buy Tell Her Tonight: Read Digital Music Reviews - Tell Her Tonight appears on the album Franz Ferdinand. Discover more music, gig and concert tickets, videos, lyrics, free downloads and MP3s, and photos with. Watch the video, get the download or listen to Dickie Greenleaf – Franz Ferdinand “Tell Her Tonight” for free. Discover more music, gig and concert tickets. Switch browsers or download Spotify for your desktop. Tell Her Tonight. By Franz Ferdinand Listen to Franz Ferdinand in full in the Spotify app. Play on Spotify. Franz Ferdinand - Tell Her Tonight (Guitar Pro) guitar pro by Franz Ferdinand We have an official Tell Her Tonight tab made by UG professional guitarists. To download “Tell Her Tonight” Guitar Pro tab click button below. Music video by Franz Ferdinand performing Tell Her Tonight (Live on Letterman). (C) CBS Interactive. Live in Taiwan Right Thoughts, Right Words, Right Action Tour. I only watched her walk, but she saw it / I only heard her talk, but she saw it / I only touched her lips but she saw it / I only kissed her lips, but she saw it. Listen to songs from the album Franz Ferdinand, including "Jacqueline", "Tell Her Tonight", "Take Me Out" and many more. Buy the album for £ Songs start. Tell Her Tonight Guitar PRO tab by Franz Ferdinand, download gtp file. Download Franz Ferdinand Tell Her Tonight free midi and other Franz Ferdinand free midi. Franz Ferdinand Tell Her Tonight With Lyrics Free Mp3 Download. Franz Ferdinand Tell Her Tonight Lyrics Wmv mp3. Free Franz Ferdinand Tell Her Tonight. -

ABO Outside the Concert Hall.Indd

MAKING EVERYDAY LIFE SPECIAL: BRITAIN’S ORCHESTRAS AND THE CREATIVE INDUSTRIES #orchestraseverywhere FOREWORD BRITAIN’S ORCHESTRAS AND THE CREATIVE INDUSTRIES Britain’s world-leading orchestras are well known for their Because of their collaboration with other parts of the creative Britain’s orchestras are world renowned, yet The anthem of the UEFA Champions League – the world’s great performances in the concert hall – and rightly so. industries, our orchestras reach not only the millions who most people have little idea of the extent of their most-watched annual sports tournament – and the music Each year, they play to more than 4.5m people in over see them in concert halls, but the billions who hear them contribution to everyday life. Outside the concert hall, for one of Disney’s most visited rides, It’s a Small World, 3,500 concerts and performances in the UK, and tour through fi lm, TV, games, pop and rock concerts and at other our professional orchestras create an enormous amount of are just two examples of this. to around 35 countries across the world. Audiences events and locations. It means that everyone can enjoy great music that is central to other entertainment across the UK And orchestras are performing and recording with top UK are growing and orchestras’ performances are increasingly music played by the world’s best orchestras. Our orchestras and around the world. and international bands and artists, like Kylie Minogue, Ray being broadcast, streamed and downloaded. are everywhere. Every year, our orchestras work with other parts of the Davies, Burt Bacharach, Boy George, Jarvis Cocker, John But performances and concerts are just one part of our The diversity of British orchestras’ work demolishes the myth creative industries to record and perform music that Grant, Clean Bandit, the Pet Shop Boys, Elbow, Kasabian, members’ work. -

Jim Abbiss Complete CV

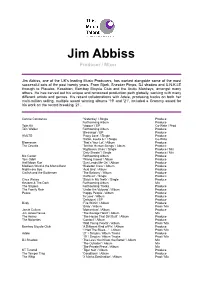

Jim Abbiss Producer / Mixer Jim Abbiss, one of the UK’s leading Music Producers, has worked alongside some of the most successful acts of the past twenty years. From Bjork, Sneaker Pimps, DJ shadow and U.N.K.LE through to Placebo, Kasabian, Bombay Bicycle Club and the Arctic Monkeys, amongst many others. He has carved out his unique and renowned production path globally, working with many different artists and genres. His recent collaborations with Adele, producing tracks on both her multi-million selling, multiple award winning albums '19' and '21', included a Grammy award for his work on the record breaking ‘21’. Connie Constance ‘Yesterday’ / Single Produce Forthcoming Album Produce Tojin Kit ‘Vapour’ / EP Co-Write / Prod Tom Walker Forthcoming Album Produce ‘Blessings’ / EP Produce HMLTD ‘Proxy Love’ / Single Produce ‘Satan, Luella & I’ / Single Co-Write Blaenavon ‘That’s Your Lot’ / Album Produce The Orwells ‘Terrible Human Beings’ / Album Produce ‘Righteous Ones’ / Single Produce / Mix ‘Dirty Sheets’ / Single Produce / Mix Nic Cester Forthcoming Album Produce Tom Odell ‘Wrong Crowd’ / Album Produce Half Moon Run ‘Sun Leads Me On’ / Album Produce Madisen Ward & the Mama Bear ‘Skeleton Crew’ / Album Produce Nightmare Boy ‘Acid Bird’ / Album Produce Catfish and the Bottlemen ‘The Balcony’ / Album Produce ‘Kathleen’ / Single Produce Circa Waves ‘Stuck in My Teeth’ / Single Produce Reuben & The Dark Forthcoming Album Mix The Strypes Forthcoming Tracks Produce The Family Rain ‘Under the Volcano’ / Album Produce Peace ‘Happy People’ /