The Bbc's Future

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Managing the BBC's Estate

Managing the BBC’s estate Report by the Comptroller and Auditor General presented to the BBC Trust Value for Money Committee, 3 December 2014 BRITISH BROADCASTING CORPORATION Managing the BBC’s estate Report by the Comptroller and Auditor General presented to the BBC Trust Value for Money Committee, 3 December 2014 Presented to Parliament by the Secretary of State for Culture, Media & Sport by Command of Her Majesty January 2015 © BBC 2015 The text of this document may be reproduced free of charge in any format or medium providing that it is reproduced accurately and not in a misleading context. The material must be acknowledged as BBC copyright and the document title specified. Where third party material has been identified, permission from the respective copyright holder must be sought. BBC Trust response to the National Audit Office value for money study: Managing the BBC’s estate This year the Executive has developed a BBC Trust response new strategy which has been reviewed by As governing body of the BBC, the Trust is the Trust. In the short term, the Executive responsible for ensuring that the licence fee is focused on delivering the disposal of is spent efficiently and effectively. One of the Media Village in west London and associated ways we do this is by receiving and acting staff moves including plans to relocate staff upon value for money reports from the NAO. to surplus space in Birmingham, Salford, This report, which has focused on the BBC’s Bristol and Caversham. This disposal will management of its estate, has found that the reduce vacant space to just 2.6 per cent and BBC has made good progress in rationalising significantly reduce costs. -

PSB Report Definitions

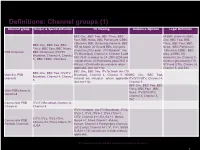

Definitions: Channel groups (1) Channel group Output & Spend definition TV Viewing Audience Opinion Legal Definition BBC One, BBC Two, BBC Three, BBC All BBC channels (BBC Four, BBC News, BBC Parliament, CBBC, One, BBC Two, BBC CBeebies, BBC streaming channels, BBC Three, BBC Four, BBC BBC One, BBC Two, BBC HD (to March 2013) and BBC Olympics News , BBC Parliament Three, BBC Four, BBC News, channels (2012 only). ITV Network* (inc ,CBeebies, CBBC, BBC PSB Channels BBC Parliament, ITV/ITV ITV Breakfast), Channel 4, Channel 5 and Alba, all BBC HD Breakfast, Channel 4, Channel S4C (S4C is added to C4 2008-2009 and channels), the Channel 3 5,, BBC CBBC, CBeebies excluded from 2010 onwards post-DSO in services (provided by ITV, Wales). HD variants are included where STV and UTV), Channel 4, applicable (but not +1s). Channel 5, and S4C. BBC One, BBC Two, ITV Network (inc ITV BBC One, BBC Two, ITV/ITV Main five PSB Breakfast), Channel 4, Channel 5. HD BBC One, BBC Two, Breakfast, Channel 4, Channel channels variants are included where applicable ITV/STV/UTV, Channel 4, 5 (but not +1s). Channel 5 BBC One, BBC Two, BBC Three, BBC Four , BBC Main PSB channels News, ITV/STV/UTV, combined Channel 4, Channel 5, S4C Commercial PSB ITV/ITV Breakfast, Channel 4, Channels Channel 5 ITV+1 Network (inc ITV Breakfast) , ITV2, ITV2+1, ITV3, ITV3+1, ITV4, ITV4+1, CITV, Channel 4+1, E4, E4 +1, More4, CITV, ITV2, ITV3, ITV4, Commercial PSB More4 +1, Film4, Film4+1, 4Music, 4Seven, E4, Film4, More4, 5*, Portfolio Channels 4seven, Channel 4 Paralympics channels 5USA (2012 only), Channel 5+1, 5*, 5*+1, 5USA, 5USA+1. -

The Market in Context

2. Television and audio visual 0 Figure 2.1 Industry metrics UK television industry 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 Total TV industry revenue (£bn) 10.5 10.6 11.1 11.2 11.1 11.7 Proportion of revenue generated by public funds 25% 25% 25% 24% 25% 23% Proportion of revenue generated by advertising 35% 33% 32% 31% 28% 30% Proportion of revenue generated by subscriptions 35% 36% 37% 39% 41% 41% TV as a proportion of total advertising spend 30% 28% 27% 27% 28% 29% Spend on originated output by 5 main networks (£bn) 3.0 2.8 2.7 2.6 2.4 2.5 Digital TV take-up 61.9% 69.7% 86.3% 87.1% 91.4% 92.5% Proportion of DTV homes paying for TV (Q1) 64% 60% 55% 53% 55% 55% Viewing per head, per day (hours) in all homes 3.65 3.60 3.63 3.74 3.75 4.04 Share of the five main channels in all homes 70% 67% 64% 61% 58% 56% Number of channels broadcasting in the UK 416 433 470 495 490 510 Source: Ofcom/broadcasters/Advertising Association/Warc/BARB/GfK. Note: Public funds include the DCMS grant to S4C and BBC funding that is allocated to TV; TV as a proportion of total advertising spend excludes direct mail and is based on Advertising Association/Warc Expenditure Report (www.warc.com/expenditurereport); spend on originations includes spend on nations and regions programming (not Welsh and Gaelic language programmes but some Irish language). Note that digital television take-up in Q1 2011 had reached 93%. -

TV Channel Distribution in Europe: Table of Contents

TV Channel Distribution in Europe: Table of Contents This report covers 238 international channels/networks across 152 major operators in 34 EMEA countries. From the total, 67 channels (28%) transmit in high definition (HD). The report shows the reader which international channels are carried by which operator – and which tier or package the channel appears on. The report allows for easy comparison between operators, revealing the gaps and showing the different tiers on different operators that a channel appears on. Published in September 2012, this 168-page electronically-delivered report comes in two parts: A 128-page PDF giving an executive summary, comparison tables and country-by-country detail. A 40-page excel workbook allowing you to manipulate the data between countries and by channel. Countries and operators covered: Country Operator Albania Digitalb DTT; Digitalb Satellite; Tring TV DTT; Tring TV Satellite Austria A1/Telekom Austria; Austriasat; Liwest; Salzburg; UPC; Sky Belgium Belgacom; Numericable; Telenet; VOO; Telesat; TV Vlaanderen Bulgaria Blizoo; Bulsatcom; Satellite BG; Vivacom Croatia Bnet Cable; Bnet Satellite Total TV; Digi TV; Max TV/T-HT Czech Rep CS Link; Digi TV; freeSAT (formerly UPC Direct); O2; Skylink; UPC Cable Denmark Boxer; Canal Digital; Stofa; TDC; Viasat; You See Estonia Elion nutitv; Starman; ZUUMtv; Viasat Finland Canal Digital; DNA Welho; Elisa; Plus TV; Sonera; Viasat Satellite France Bouygues Telecom; CanalSat; Numericable; Orange DSL & fiber; SFR; TNT Sat Germany Deutsche Telekom; HD+; Kabel -

Academy the State of Product Management 2010

The State of Product Management 2010 Nic Newman Academy The State of Product Management 2010 A study of product management best practice in UK digital media CONTENTS Methodology and acknowledgments Executive summary and conclusions 1. The role of product management 2. The emerging product development process 3. Case studies 3.1. The Guardian 3.2. BBC iPlayer 3.3. Channel 4.com 3.4. Huddle.com 3.5. BBC Weather 3.6. Mobile IQ 3.7. BBC Wildlife Finder 4. Masterclass interviews 4.1. Anthony Rose – BBC (iPlayer/YouView) 4.2. Hunter Walk ‐ YouTube 5. Conclusions: The secrets of product success Glossary Interviewees Bibliography 1 THE AUTHOR: Nic Newman played a key role in shaping the BBC’s internet services over more than a decade. He was a founding member of the BBC News Website, leading international coverage as World Editor (1997‐2001). As Head of Product Development for BBC News he helped introduce innovations such as blogs, podcasting and on‐demand video. Most recently he led digital teams, developing websites, mobile and interactive TV applications for News, Sport, Weather and Local. Nic is currently a Visiting Fellow at the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism where he has published two recent reports on social media and mainstream media. He is a trainer, writer and consultant on digital media at the interface between technology and journalism. METHODOLOGY AND ACKNOWLEDGMENTS: This study was completed in June and July 2010 and aims to explore product management best practice in the digital media industry. It aims to raise the profile and understanding of the importance of the role of the product manager in the creation of successful digital products through interviews and case studies. -

“Authentic” News: Voices, Forms, and Strategies in Presenting Television News

International Journal of Communication 10(2016), 4239–4257 1932–8036/20160005 Doing “Authentic” News: Voices, Forms, and Strategies in Presenting Television News DEBING FENG1 Jiangxi University of Finance and Economics, China Unlike print news that is static and mainly composed of written text, television news is dynamic and needs to be delivered with diversified presentational modes and forms. Drawing upon Bakhtin’s heteroglossia and Goffman’s production format of talk, this article examined the presentational forms and strategies deployed in BBC News at Ten and CCTV’s News Simulcast. It showed that the employment of different presentational elements and forms in the two programs reflects two contrasting types of news discourse. The discourse of BBC News tends to present different, and even confrontational, voices with diversified presentational forms, such as direct mode of address and “fresh talk,” thus likely to accentuate the authenticity of the news. The other type of discourse (i.e., CCTV News) seems to prefer monologic news presentation and prioritize studio-based, scripted news reading, such as on-camera address or voice- overs, and it thus creates a single authoritative voice that is likely to undermine the truth of the news. Keywords: authenticity, mode of address, presentational elements, voice, television news The discourse of television news has been widely studied within the linguistic world. Early in the 1970s, researchers in the field of critical linguistics (CL; e.g., Fowler, 1991; Fowler, Hodge, Kress, & Trew, 1979; Hodge & Kress, 1993) paid great attention to the ideological meaning of news by drawing upon a kit of linguistic tools such as modality, transitivity, and transformation. -

BBC Chair Role Spec

Chair, BBC We are looking for an outstanding individual with demonstrable leadership skills and a passion for the media and public broadcasting, to represent the public interest in the BBC and maintain the Corporation's independence. As per the BBC Royal Charter, the Chair of the BBC Board must be appointed by Order in Council following a fair and open competition. The Governance Code, including the public appointment principles, must be followed in making the appointment. The Commissioner for Public Appointments will ensure that the appointment is made in accordance with the Governance Code. Candidates should be aware that the preferred candidate for the post of Chair will be required to appear before a Parliamentary Select Committee prior to appointment. About the BBC The BBC’s mission is defined by Royal Charter: to act in the public interest, serving all audiences through the provision of impartial, high-quality and distinctive output and services which inform, educate and entertain. The BBC is required to do this through delivering five public purposes: 1. To provide impartial news and information to help people understand and engage with the world around them; 2. To support learning for people of all ages; 3. To show the most creative, highest quality and distinctive output and services; 4. To reflect, represent and serve the diverse communities of all of the United Kingdom’s nations and regions and, in doing so, support the creative economy across the United Kingdom; and, 5. To reflect the United Kingdom, its culture and values to the world. The BBC is a public corporation, independent in all matters concerning the fulfilment of its mission and the promotion of the public purposes. -

Diversity and Inclusion in the European Audiovisual Sector European Audiovisual Observatory, Strasbourg, 2021 ISSN 2079-1062 ISBN 978-92-871-9054-3 (Print Version)

Diversity and inclusion in the European audiovisual sector IRIS Plus IRIS Plus 2021-1 Diversity and inclusion in the European audiovisual sector European Audiovisual Observatory, Strasbourg, 2021 ISSN 2079-1062 ISBN 978-92-871-9054-3 (Print version) Director of publication – Susanne Nikoltchev, Executive Director Editorial supervision – Maja Cappello, Head of Department for Legal Information Editorial team – Francisco Javier Cabrera Blázquez, Julio Talavera Milla, Sophie Valais Research assistant - Léa Chochon European Audiovisual Observatory Authors (in alphabetical order) Francisco Javier Cabrera Blázquez, Maja Cappello, Julio Talavera Milla, Sophie Valais Translation Marco Polo Sarl, Sonja Schmidt Proofreading Jackie McLelland, Johanna Fell, Catherine Koleda Editorial assistant – Sabine Bouajaja Press and Public Relations – Alison Hindhaugh, [email protected] European Audiovisual Observatory Publisher European Audiovisual Observatory 76, allée de la Robertsau, 67000 Strasbourg, France Tel.: +33 (0)3 90 21 60 00 Fax: +33 (0)3 90 21 60 19 [email protected] www.obs.coe.int Cover layout – ALTRAN, France Please quote this publication as Cabrera Blázquez F.J., Cappello M., Talavera Milla J., Valais S., Diversity and inclusion in the European audiovisual sector, IRIS Plus, European Audiovisual Observatory, Strasbourg, April 2021 © European Audiovisual Observatory (Council of Europe), Strasbourg, 2021 Opinions expressed in this publication are personal and do not necessarily represent the views of the Observatory, its members or the Council of Europe. Diversity and inclusion in the European audiovisual sector Francisco Javier Cabrera Blázquez, Maja Cappello, Julio Talavera Milla, Sophie Valais Foreword Let me tell you a few stories about extraordinary people. Artemisia Gentileschi was a seventeenth century painter, and quite a talented one at that. -

BBC B R O a D C a S T I N G

D E A L S O F T H E Y E A R SECURITISATION: BBC B r o a d c a s t i n g THE BRITISH BROADCASTING CORPORATION (BBC), in existence for almost 80 years, experienced a first this year. The group, governed by successive Royal Charters since its inception in 1926, launched its first-ever capital markets transaction in 2003 with a groundbreaking bond issue and securitisation for Broadcasting House, the flagship property and London headquarters of the BBC, which will become the world’s largest live c e n t r a l broadcast centre. 58 THE TREASURER JAN | FEB 2004 Corporate profile The BBC has been in existence for television services, network and local Principal terms of the almost 80 years, governed by radio and online services. The Wo r l d £813m securitisation successive Royal Charters in the UK. S e rvice is its international radio and The group has businesses along three online service (funded by direct grant Amount £813m main strands: public serv i c e from the Foreign & C o m m o n w e a l t h Type Fixed broadcasting in the UK is funded by Office). And BBC Commercial Margin 52bp the annual UK licence fees and Holdings coordinates activity across Maturity July 2033 includes delivery of free-to-air the BBC’s commercial businesses. Bookrunners Morgan Stanley The BBC first began looking at ways to develop its portfolio of over 500 together the transaction with Ernst & Young appointed as additional advisor. The properties back in 1999. -

What Is Bbc Three?

We tested the public value of the proposed changes using a combination of quantitative and qualitative methodologies Quantitative methodology Qualitative methodology We ran a 15 minute online survey with 3,281 respondents to We conducted 20 x 2 hour ‘Extended Group’ sessions via Zoom with understand current associations with BBC Three, the appeal of BBC a mix of different audiences to explore and compare reactions, Three launching as a linear channel, and how this might impact from a personal and societal value perspective, to the concept of existing services in the market. BBC Three becoming a linear channel again. In the survey, we explored the following: In the sessions, we explored the following: - Demographics and brand favourability - Linear TV consumption and BBC attitudes - Current TV and video consumption - (S)VOD consumption behaviours, with a focus on BBC Three - BBC Three awareness, usage and perceptions (current) - A BBC Three content evaluation (via BBC Three on iPlayer exploration) - Likelihood of watching new TV channel and perceptions - Responses to the proposal of BBC Three becoming a TV channel - Impact on services currently used (including time taken away from each) - Expected personal and societal impact of the proposed changes - Societal impact of BBC Three launching as a TV channel - Evaluation of proposed changes against BBC Public Purposes 4 The qualitative stage involved 20 x 2-hour extended digital group discussions across the UK with a carefully designed sample 20 x 2 hour Extended Zoom Groups The qualitative -

Platform for Success: Final Report of the Scottish Broadcasting Commission

PLATFORM FOR SUCCESS Final report of the Scottish Broadcasting Commission PLATFORM FOR SUCCESS Final report of the Scottish Broadcasting Commission © Crown copyright 2008 ISBN: 978-0-7559-5845-0 The Scottish Government St Andrew’s House Edinburgh EH1 3DG Produced for the Scottish Broadcasting Commission by RR Donnelley B57086 Published by the Scottish Government, September, 2008 Further copies are available from Blackwell's Bookshop 53 South Bridge Edinburgh EH1 1YS Scottish Broadcasting Commission : 01 CONTENTS Foreword 2 Executive Summary 3 Chapter 1 Introduction 13 Chapter 2 Our Vision for Scottish Broadcasting 15 Chapter 3 Serving Audiences and Society 19 Chapter 4 A Network for Scotland 32 Chapter 5 Broadcasting and the Creative Economy 39 Chapter 6 Delivering the Future 51 Annex 56 02 : Scottish Broadcasting Commission FOREWORD In its short existence, the Scottish Broadcasting Commission has triggered a wide-ranging and frequently passionate debate about the future of the industry and the services it provides to audiences in Scotland. We intended from the beginning to make an impact which would lead to action, and there have been some encouraging early results in the form of new commitments from the broadcasters. But this is only a start. In publishing our final report and recommendations, we hope and expect that the debate will become even more visible and audible – with particular focus on the key opportunities and challenges we have identified in broadcasting and the new digital platforms. What has been refreshing is the extent to which both the industry and its audiences are at least as excited about the future as they are critical of some of the weaknesses of the past and present. -

BBC Learning – Commissioning Meeting

BBC Learning – Commissioning Meeting May 2012 Welcome and Introduction Saul Nassé – Controller, BBC Learning BBC North • BBC Learning is now located at MediaCityUK, Salford • The move to Salford aims to ensure we better serve and reflect Northern audiences • Other departments based here include: o Sport o Children’s o 5 live o Future Media o BBC Breakfast Welcome and Introduction • Our fourth session to share plans and future thinking • This is the second of two sessions held today: o AM – aimed at education publishers and distributors o PM – commissioning meeting for BBC suppliers • Minutes and recordings of both events will be put online Welcome and Introduction At the last meeting in October 2011 we covered: o Update on Learning activity and content o Information on BBC Learning online activity and plans o Emerging thoughts on the Knowledge and Learning Product o Information on BBC Learning television and Learning Zone plans o Update on finance and public affairs activity Agenda model Timing Agenda Item Speaker 2.30pm Introduction and Welcome Saul Nassé – Controller, BBC Learning Learning and Strategy Update The Knowledge and Learning Product Saul Nassé – Controller, BBC Learning Chris Sizemore – Executive Editor, BBC Learning BBC Learning Online Commissioning Chris Sizemore – Executive Editor, BBC Learning BBC Learning Television Abigail Appleton – Head of Commissioning, BBC Learning BBC Two: The Learning Zone Katy Jones – Executive Producer, BBC Learning Finance and Industry Engagement Alex Lloyd – Head of Operations and Public Affairs,