Sympathy for the Devil: State Engagement with Criminal Organisations in Furtherance of Public Policy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Organized Crime and Terrorist Activity in Mexico, 1999-2002

ORGANIZED CRIME AND TERRORIST ACTIVITY IN MEXICO, 1999-2002 A Report Prepared by the Federal Research Division, Library of Congress under an Interagency Agreement with the United States Government February 2003 Researcher: Ramón J. Miró Project Manager: Glenn E. Curtis Federal Research Division Library of Congress Washington, D.C. 20540−4840 Tel: 202−707−3900 Fax: 202−707−3920 E-Mail: [email protected] Homepage: http://loc.gov/rr/frd/ Library of Congress – Federal Research Division Criminal and Terrorist Activity in Mexico PREFACE This study is based on open source research into the scope of organized crime and terrorist activity in the Republic of Mexico during the period 1999 to 2002, and the extent of cooperation and possible overlap between criminal and terrorist activity in that country. The analyst examined those organized crime syndicates that direct their criminal activities at the United States, namely Mexican narcotics trafficking and human smuggling networks, as well as a range of smaller organizations that specialize in trans-border crime. The presence in Mexico of transnational criminal organizations, such as Russian and Asian organized crime, was also examined. In order to assess the extent of terrorist activity in Mexico, several of the country’s domestic guerrilla groups, as well as foreign terrorist organizations believed to have a presence in Mexico, are described. The report extensively cites from Spanish-language print media sources that contain coverage of criminal and terrorist organizations and their activities in Mexico. -

ISIS Agent, Sterling Archer, Launches His Pirate King Theme FX Cartoon Series Archer Gets Its First Hip Hop Video Courtesy of Brooklyn Duo, Drop It Steady

ISIS agent, Sterling Archer, launches his Pirate King Theme FX Cartoon Series Archer Gets Its First Hip Hop Video courtesy of Brooklyn duo, Drop it Steady Fans of the FX cartoon series Archer do not need to be told of its genius. The show was created by many of the same writers who brought you the Fox series Arrested Development. Similar to its predecessor, Archer has built up a strong and loyal fanbase. As with most popular cartoons nowadays, hip-hop artists tend to flock to the animated world and Archer now has it's hip-hop spin off. Brooklyn-based music duo, Drop It Steady, created a fun little song and video sampling the show. The duo drew their inspiration from a series sub plot wherein Archer became a "pirate king" after his fiancée was murdered on their wedding day in front of him. For Archer fans, the song and video will definitely touch a nerve as Drop it Steady turns the story of being a pirate king into a forum for discussing recent break ups. Video & Music Download: http://www.mediafire.com/?bapupbzlw1tzt5a Official Website: http://www.dropitsteady.com Drop it Steady on Facebook: http://www.facebook.com/dropitsteady About Drop it Steady: Some say their music played a vital role in the Arab Spring of 2011. Others say the organizers of Occupy Wall Street were listening to their demo when they began to discuss their movement. Though it has yet to be verified, word that the first two tracks off of their upcoming EP, The Most Interesting EP In The World, were recorded at the ceremony for Prince William and Katie Middleton and are spreading through the internets like wild fire. -

Merchants of Menace: the True Story of the Nugan Hand Bank Scandal Pdf, Epub, Ebook

MERCHANTS OF MENACE: THE TRUE STORY OF THE NUGAN HAND BANK SCANDAL PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Peter Butt | 298 pages | 01 Nov 2015 | Peter Butt | 9780992325220 | English | Australia Merchants of Menace: The True Story of the Nugan Hand Bank Scandal PDF Book You They would then put it up for sale through a Panama-registered company at full market value. We get a close-up of his fearsome Vietnam exploits in interviews with Douglas Sapper, a combat buddy from the days of Special Forces training. Take it, smoke it, give yourself a shot, just get rid of it. No trivia or quizzes yet. With every sale Mike and Bud earned a tidy 25 per cent commission. In fact, throughout military training the thing you noticed about Michael was that he was driven. But he dropped out and took a position 22 2 Jurisprudence is crap with the Canadian public service, giving him an income with which he could feed his penchant for fast cars, girls and gliding lessons. Sapper had contacts all the way up and down the Thai food chain; he warned Hand of the obvious perils of setting up business in that part of the world: Chiang Mai is the Wild West, the hub of good and evil, but mostly evil. It was evident that the embryonic bank had been outlaying far more money than it was earning: It became very clear to me that Nugan Hand had the trappings of a bank, but it was so much window dressing. During the Vietnam War, he dished out drugs, legal and illegal, to his military colleagues and friends, including Rolling Stone journalist Hunter S Thompson. -

Gangs Beyond Borders

Gangs Beyond Borders California and the Fight Against Transnational Organized Crime March 2014 Kamala D. Harris California Attorney General Gangs Beyond Borders California and the Fight Against Transnational Organized Crime March 2014 Kamala D. Harris California Attorney General Message from the Attorney General California is a leader for international commerce. In close proximity to Latin America and Canada, we are a state laced with large ports and a vast interstate system. California is also leading the way in economic development and job creation. And the Golden State is home to the digital and innovation economies reshaping how the world does business. But these same features that benefit California also make the state a coveted place of operation for transnational criminal organizations. As an international hub, more narcotics, weapons and humans are trafficked in and out of California than any other state. The size and strength of California’s economy make our businesses, financial institutions and communities lucrative targets for transnational criminal activity. Finally, transnational criminal organizations are relying increasingly on cybercrime as a source of funds – which means they are frequently targeting, and illicitly using, the digital tools and content developed in our state. The term “transnational organized crime” refers to a range of criminal activity perpetrated by groups whose origins often lie outside of the United States but whose operations cross international borders. Whether it is a drug cartel originating from Mexico or a cybercrime group out of Eastern Europe, the operations of transnational criminal organizations threaten the safety, health and economic wellbeing of all Americans, and particularly Californians. -

Archer Season 1 Episode 9

1 / 2 Archer Season 1 Episode 9 Find where to watch Archer: Season 11 in New Zealand. An animated comedy centered on a suave spy, ... Job Offer (Season 1, Episode 9) FXX. Line of the .... Lookout Landing Podcast 119: The Mariners... are back? 1 hr 9 min.. The season finale of "Archer" was supposed to end the series. ... Byer, and Sterling Archer, voice of H. Jon Benjamin, in an episode of "Archer.. Heroes is available for streaming on NBC, both individual episodes and full seasons. In this classic scene from season one, Peter saves Claire. Buy Archer: .... ... products , is estimated at $ 1 billion to $ 10 billion annually . ... Douglas Archer , Ph.D. , director of the division of microbiology in FDA's Center for Food ... Food poisoning is not always just a brief - albeit harrowing - episode of Montezuma's revenge . ... sampling and analysis to prevent FDA Consumer / July - August 1988/9.. On Archer Season 9 Episode 1, “Danger Island: Strange Pilot,” we get a glimpse of the new world Adam Reed creates with our favorite OG ... 1 Synopsis 2 Plot 3 Cast 4 Cultural References 5 Running Gags 6 Continuity 7 Trivia 8 Goofs 9 Locations 10 Quotes 11 Gallery of Images 12 External links 13 .... SVERT Na , at 8 : HOMAS Every Evening , at 9 , THE MANEUVRES OF JANE ... HIT ENTFORBES ' SEASON . ... Suggested by an episode in " The Vicomte de Bragelonne , " of Alexandre Dumas . ... Norman Forbes , W. H. Vernon , W. L. Abingdon , Charles Sugden , J. Archer ... MMG Bad ( des Every Morning , 9.30 to 1 , 38.. see season 1 mkv, The Vampire Diaries Season 5 Episode 20.mkv: 130.23 .. -

Obama-C.I.A. Links

o CO Dispatch "The issue is not issues; the issue is the system" —Ronnie Dugger Newsletter of the January-February Boston-Cambridge Alliance for Democracy 2011 Barack Obama is neither weak nor is he stupid. He knows exactly what he is doing. He is cynically carrying out the pre- cise bidding of his corporate/military masters, while rhetorically faking-out everyday Black, White, Brown, Red, and Yellow people with his endless bait and switch tactics. —Larry Pinkney, Black Commentator Barack Obama (right) with his mother Ann Dunham, step-father Lolo Soetoro, and infant half-sister Maya. Dunham worked in several CIA COMMUNITY NOTES front groups in Hawai'i and Indonesia, and Colonel Soetoro helped Don't be left out! Join the BCA/NorthBridge planning group! overthrow Indonesia's president Sukarno in a CIA-sponsored coup. Our next meeting will be Tuesday, 4 January, 7:30, in the AfD After graduating from Columbia University, Obama worked for a CIA- office at 760 Main St., Waltham MA. Info: 781-894-1179. sponsored international business seminar group. Current projects: "bottled water ban in Concord "supporting ousted city councilor Chuck Turner "building support for Move Obama-C.I.A. Links to Amend (anti-corporate-personhood) and progressive Self and Principal Relatives All Involved campaign finance legislation "participatory budgeting by Sherwood Ross, grantlawrence.blogspot.com, 2 Sep 2010 conference in April "developing a trade advisory committee to seed and bird-dog the new MA citizen trade commission. RESIDENT OBAMA—AS WELL AS HIS MOTHER, FATHER, STEP- Turn to Page 16 for notes on these and other local matters.. -

A Plausibly Deniable Encryption Scheme for Personal Data Storage Andrew Brockmann Harvey Mudd College

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont HMC Senior Theses HMC Student Scholarship 2015 A Plausibly Deniable Encryption Scheme for Personal Data Storage Andrew Brockmann Harvey Mudd College Recommended Citation Brockmann, Andrew, "A Plausibly Deniable Encryption Scheme for Personal Data Storage" (2015). HMC Senior Theses. 88. https://scholarship.claremont.edu/hmc_theses/88 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the HMC Student Scholarship at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in HMC Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Plausibly Deniable Encryption Scheme for Personal Data Storage Andrew Brockmann Talithia D. Williams, Advisor Arthur T. Benjamin, Reader Department of Mathematics May, 2015 Copyright © 2015 Andrew Brockmann. The author grants Harvey Mudd College and the Claremont Colleges Library the nonexclusive right to make this work available for noncommercial, educational pur- poses, provided that this copyright statement appears on the reproduced materials and notice is given that the copying is by permission of the author. To disseminate otherwise or to republish requires written permission from the author. Abstract Even if an encryption algorithm is mathematically strong, humans in- evitably make for a weak link in most security protocols. A sufficiently threatening adversary will typically be able to force people to reveal their encrypted data. Methods of deniable encryption seek to mend this vulnerability by al- lowing for decryption to alternate data which is plausible but not sensitive. Existing schemes which allow for deniable encryption are best suited for use by parties who wish to communicate with one another. -

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 105 CONGRESS, SECOND SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 105 CONGRESS, SECOND SESSION Vol. 144 WASHINGTON, THURSDAY, MAY 7, 1998 No. 56 House of Representatives The House met at 10 a.m. and was ance and keep them from the evil one. PASTOR KENNETH G. WILDE called to order by the Speaker pro tem- Inspire them with a heart for our Na- (Mrs. CHENOWETH asked and was pore (Mr. LATOURETTE). tion. Sanctify them with Your truth, given permission to address the House f for Your word is truth. May they know for 1 minute.) Your love and see Your glory. May Mrs. CHENOWETH. Mr. Speaker, it is DESIGNATION OF THE SPEAKER they all understand, as Esther did, that indeed an honor and a privilege for me PRO TEMPORE just very possibly they have been to welcome to this House of Represent- The SPEAKER pro tempore laid be- brought to the Kingdom for such a atives my pastor from Boise, Idaho, fore the House the following commu- time as this. Ken Wilde. Pastor Wilde is the senior nication from the Speaker: Now, as Daniel prayed, we also pray. pastor of the Capital Christian Center, WASHINGTON, DC, Oh, Lord, hear. Oh, Lord, forgive. Oh, a church that has a membership of May 7, 1998. Lord, listen and act. Do not delay for about 2,000 and is growing very quickly I hereby designate the Honorable STEVE your own sake, my God, for Your city in Boise, Idaho. LATOURETTE to act as Speaker pro tempore and Your people who are called by Pastor Wilde is not only the senior on this day. -

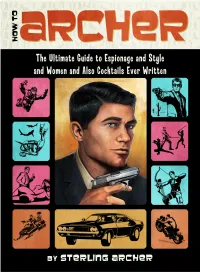

Howtoarcher Sample.Pdf

Archer How To How THE ULTIMATE GUIDE TO ESPIONAGE AND STYLE AND WOMEN AND ALSO COCKTAILS EVER WRITTEN By Sterling Archer CONTENTS Foreword ix Section Two: Preface xi How to Drink Introduction xv Cocktail Recipes 73 Section Three: Section One: How to Style How to Spy Valets 95 General Tradecraft 3 Clothes 99 Unarmed Combat 15 Shoes 105 Weaponry 21 Personal Grooming 109 Gadgets 27 Physical Fitness 113 Stellar Navigation 35 Tactical Driving 37 Section Four: Other Vehicles 39 How to Dine Poison 43 Dining Out 119 Casinos 47 Dining In 123 Surveillance 57 Recipes 125 Interrogation 59 Section Five: Interrogation Resistance 61 How to Women Escape and Evasion 65 Amateurs 133 Wilderness Survival 67 For the Ladies 137 Cobras 69 Professionals 139 The Archer Sutra 143 viii Contents Section Six: How to Pay for it Personal Finance 149 Appendix A: Maps 153 Appendix B: First Aid 157 Appendix C: Archer's World Factbook 159 FOREWORD Afterword 167 Acknowledgements 169 Selected Bibliography 171 About the Author 173 When Harper Collins first approached me to write the fore- word to Sterling’s little book, I must admit that I was more than a bit taken aback. Not quite aghast, but definitely shocked. For one thing, Sterling has never been much of a reader. In fact, to the best of my knowledge, the only things he ever read growing up were pornographic comic books (we used to call them “Tijuana bibles,” but I’m sure that’s no longer considered polite, what with all these immigrants driving around every- where in their lowriders, listening to raps and shooting all the jobs). -

ACLU Facial Recognition–Jeffrey.Dalessio@Eastlongmeadowma

Thursday, May 7, 2020 at 1:00:56 PM Eastern Daylight Time Subject: IACP's The Lead: US A1orney General: Police Officers Deserve Respect, Support. Date: Monday, December 23, 2019 at 7:48:58 AM Eastern Standard Time From: The IACP To: jeff[email protected] If you are unable to see the message or images below, click here to view Please add us to your address book GreeWngs Jeffrey Dalessio Monday, December 23, 2019 POLICING & POLICY US AHorney General: Police Officers Deserve Respect, Support In an op-ed for the New York Post (12/16) , US A1orney General William barr writes, “Serving as a cop in America is harder than ever – and it comes down to respect. A deficit of respect for the men and women in blue who daily put their lives on the line for the rest of us is hurWng recruitment and retenWon and placing communiWes at risk.” barr adds, “There is no tougher job in the country than serving as a law-enforcement officer. Every morning, officers across the country get up, kiss their loved ones and put on their protecWve vests. They head out on patrol never knowing what threats and trials they will face. And their families endure restless nights, so we can sleep peacefully.” Policing “is only geng harder,” but “it’s uniquely rewarding. Law enforcement is a noble calling, and we are fortunate that there are sWll men and women of character willing to serve selflessly so that their fellow ciWzens can live securely.” barr argues that “without a serious focus on officer retenWon and recruitment, including a renewed appreciaWon for our men and women in blue, there won’t be enough police officers to protect us,” and “support for officers, at a minimum, means adequate funding. -

Mobihydra: Pragmatic and Multi-Level Plausibly Deniable Encryption Storage for Mobile Devices?

MobiHydra: Pragmatic and Multi-Level Plausibly Deniable Encryption Storage for Mobile Devices? Xingjie Yuy;z;\, Bo Chen], Zhan Wangy;z;??, Bing Changy;z;\, Wen Tao Zhuz;y, and Jiwu Jingy;z y State Key Laboratory of Information Security, Institute of Information Engineering, Chinese Academy of Sciences, CHINA z Data Assurance and Communication Security Research Center, Chinese Academy of Sciences, CHINA \ University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, CHINA ] Department of Computer Science, Stony Brook University, USA Email: [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Abstract. Nowadays, smartphones have started being used as a tool to collect and spread po- litically sensitive or activism information. The exposure of the possession of such sensitive data shall pose a risk in severely threatening the life safety of the device owner. For instance, the data owner may be caught and coerced to give away the encryption keys so that the encryption alone is inadequate to mitigate such risk. In this work, we present MobiHydra, a pragmatic plausibly deniable encryption (PDE) scheme featuring multi-level deniability on mobile devices, to circumvent the coercive attack. MobiHydra is pragmatic in that it remarkably supports hiding opportunistic data without necessarily rebooting the device. In addition, MobiHydra favourably mitigates the so-called booting-time defect, which is a whistle-blower to expose the usage of PDE in previous solutions. We implement a prototype for MobiHydra on Google Nexus S. The evaluation results demonstrate that MobiHydra introduces very low overhead compared with other PDE solutions for mobile devices. -

Narcocultura As Cultural Capital for Latinx Youth Identity Work: an Online Ethnography

University of Texas at El Paso ScholarWorks@UTEP Open Access Theses & Dissertations 2019-01-01 Narcocultura As Cultural Capital For Latinx Youth Identity Work: An Online Ethnography Emiliano Villarreal University of Texas at El Paso Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.utep.edu/open_etd Part of the Inequality and Stratification Commons, Liberal Studies Commons, Other Education Commons, Other Sociology Commons, Quantitative, Qualitative, Comparative, and Historical Methodologies Commons, and the Sociology of Culture Commons Recommended Citation Villarreal, Emiliano, "Narcocultura As Cultural Capital For Latinx Youth Identity Work: An Online Ethnography" (2019). Open Access Theses & Dissertations. 2908. https://digitalcommons.utep.edu/open_etd/2908 This is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UTEP. It has been accepted for inclusion in Open Access Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UTEP. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NARCOCULTURA AS CULTURAL CAPITAL FOR LATINX YOUTH IDENTITY WORK: AN ONLINE ETHNOGRAPHY EMILIANO VILLARREAL Doctoral Program in Teaching, Learning, and Culture APPROVED: Katherine S. Mortimer, Ph.D., Chair Amy J. Bach, Ed.D. Char Ullman, Ph.D. Eduardo Barrera Herrera, Ph.D. Stephen Crites, Ph.D. Dean of the Graduate School Copyright © by Emiliano Villarreal 2019 NARCOCULTURA AS CULTURAL CAPITAL FOR LATINX YOUTH IDENTITY WORK: AN ONLINE ETHNOGRAPHY by EMILIANO VILLARREAL, M.S., B.A. DISSERTATION Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at El Paso in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of Teacher Education THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT EL PASO December 2019 Acknowledgements I could have never completed this dissertation project without the years of support I received from the faculty at the Department of Teacher Education of the University of Texas at El Paso, in particular from my dissertation committee chair, Dr.