West Virginia Race Relations at The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

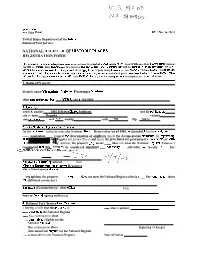

Nomination Form

(Rtv. 10-90) 3-I5Form 10-9fMN United States Department of the loterior National Park Service NATIONAL MGISTER OF HTSTORTC PLACXS REGISTRATION FORM Thiq fMm is for use in nomvlaring or requesting detnminatiwts for indin'dd propenies and di-. See immtct~onsin How m Cornplerc the National Regi~terof Wistnnc P1w.s Regaht~onForm (National Rcicpistcr Bullctin I6A) Complm each Item by mark~ng"x" m the appmprlalc box or b! entermp lhc mfommion requested If my ircm dm~wt apph to toe prombeing dwumemad. enter WfA" for "MIappliable." For functions. arch~tccruralclass~ficatron. materials, adarras of s~mificance.enm only -ones and subcak-gmcs from the rnswctions- Pl- addmonal enmcs md nmtive ncrns on continuation sheets MPS Form 10-9OOa). Use a tJ.pewritcr, word pmsor,or computer, to complete: all tterrus I. Name of Property historic name Virginian Railway Passenger Station other nameskite number VOHR site # 128-5461 2, Loration street & number 1402 Jefferson Street Southeast not for publica~ion city or town Roanoke vicinity state Veinia codcVA county code 770 Zip 24013 3. SlatelFderat Agencv Certification As the desipated authority under the National FIistoric Reservation An of 1986, as amended, 1 hereby certifj. that this -nomination -request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standads for regisrering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set fonh in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property -X- meets -does not meet the National Rcgister Criteria. I recommend that this pmwbe considered significant - nationally - statewide -X- locally. ( - See -~wments.)C ~ipnature~fcerti$ng official Date Viwinia De~srtrnentof Historic Resources Sme- or Federal agency rrnd bureau-- In my opinion, the property -meets -does not meet the National Register criteria. -

A Briny Crossroads Salt, Slavery, and Sectionalism in the Kanawha Salines

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Dissertations and Theses City College of New York 2014 A Briny Crossroads Salt, Slavery, and Sectionalism in The Kanawha Salines Cyrus Forman CUNY City College How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/cc_etds_theses/275 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] A Briny Crossroads Salt, Slavery, and Sectionalism in The Kanawha Salines Author: Cyrus Forman Adviser: Craig Daigle May 01, 2014. Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts of the City College of the City University of New York. 1 Table of Contents Introduction………………………………………….. ……...3 Slavery Comes to The Kanawha Salines……………………..9 Forming an Interracial Working Class Culture……………..23 A Housed Divided…………………………………………..39 Conclusion…………………………………………………..45 Bibliography………………………………………………...51 Appendix…………………………………………………...57 2 I. Introduction: The birth and disappearance of the West Virginia salt industry The Kanawha Salines are a place whose history challenges conventional narratives and popular assumptions about slavery and freedom in the antebellum South. The paradoxical nature of slavery in this locale can be seen in the identity of the first documented people forced to labor in the salt works. A half century before enslaved Africans were imported to this region, European women and their families were kidnapped, enslaved, and marched to the salt mines by Native Americans: “In 1755, the Indians had carried Mary Ingles, her newborn baby, and others as captives....to this spot on the Kanawha to attain a salt supply.”1 Mary Ingles’ time in slavery was brief; like some of the African-American slaves who would perform similar work a half century later, she fled captivity in the salt mines and followed a river to freedom. -

“Ruffners Return”

opportunity to hear Larry Rowe—attorney, historian and lecturer—speak of our ancestors in ways we had never before heard or imagined. Assembled in the 135 year-old African Zion Church, approximately 75 members of our family appeared spellbound as Larry wondered aloud about “life around the kitchen table” at the David Ruffner household. RUFFNER ROOTS & RAMBLINGS Published quarterly by the RUFFNER FAMILY ASSOCIATION Volume 18, Issue 2, Summer 2015 “Ruffners Return” Over the past 18 years, we have had the opportunity to attend Ruffner Reunions through- out various parts of the country. By far, the one in Charleston/Malden, WV, this year was the Larry Rowe most meaningful to me. From the moment we (photo by Jim McNeely) arrived at the Holiday Inn, I knew this one was going to be something special. The first thing we Seated there was David, entrepreneur and in- saw upon checking-in was the front-page article ventor, who founded a method of extracting salt from The Charleston Gazette (see page 6) about (later, oil and gas) from the earth that was a first- the “Ruffners return” to Charleston. I knew, then, of-its-kind invention in Western civilization; that our Joseph Ruffner descendants had not been Henry, the Presbyterian Minister, who organized forgotten. Charleston's Presbyterian congregation and per- sonally built the Kanawha Salines Presbyterian What made it special? I don't know if it was our Church in Malden brick by brick; William Henry, family members sitting in the hotel lobby “telling the designer of and first Superintendent of family stories,” or whether just being together as Virginia's public school system; General Lewis a “family,” the positive factor. -

Landscape and History at the Headwaters of the Big Coal River

Landscape and History at the Headwaters of the Big Coal River Valley An Overview By Mary Hufford Reading the Landscape: An Introduction “This whole valley’s full of history.” -- Elsie Rich, Jarrold’s Valley From the air today, as one flies westward across West Virginia, the mountains appear to crest in long, undulating waves, giving way beyond the Allegheny Front to the deeply crenulated mass of the coal-bearing Allegheny plateaus. The sandstone ridges of Cherry Pond, Kayford, Guyandotte, and Coal River mountains where the headwaters of southern West Virginia’s Big Coal River rise are the spectacular effect of millions of years of erosion. Here, water cutting a downward path through shale etched thousands of winding hollows and deep valleys into the unglaciated tablelands of the plateaus. Archeologists have recovered evidence of human activity in the mountains only from the past 12,000 years, a tiny period in the region’s ecological development. Over the eons it took to transform an ancient tableland into today’s mountains and valleys, a highly differentiated forest evolved. Known among ecologists as the mixed mesophytic forest, it is the biologically richest temperate-zone hardwood system in the world. And running in ribbons beneath the fertile humus that anchors the mixed mesophytic are seams of coal, the fossilized legacy of an ancient tropical forest, submerged and compressed during the Paleozoic era beneath an inland sea.1 Many of the world’s mythologies explain landforms as the legacies of struggles among giants, time out of mind. Legend accounts for the Giant’s Causeway, a geological formation off the coast of Northern Ireland, as the remains of an ancient bridge that giants made between Ireland and Scotland. -

About Our High School

About Our High School Digitized by: Max Isaksen 22 Aug 2018 About Fairhaven High School A booklet to acquaint students of Fairhaven High School with little-known facts about their school. COMPILED BY A SENIOR ENGLISH CLASS IN 1954 Mimeographing by courtesy of the Business Department of Fairhaven High School Funded by the Fairhaven High School Alumni Association PREFACE To those of its faculty, students and alumni who love Fairhaven High School, it comes, as a distinct shock to realize that very little authentic information about the school is available. We walk its corridors, realizing that we are indeed surrounded by beauty, but so used have we become to the unique qualities of our school, that we are no longer sensitive to its artistic appeal, curious about its history or grateful for its very distinct advantages. As the years creep on, information about the past of F.H.S. is harder and harder to come by. Charming legends and personal antidotes about the building and its founder are lost---carried only as they have been heretofore---on the tongues of those who gradually are passing from our scene. It has been felt, therefore, that there has developed a very real need to get down in black and white, facts about our school that can now be discovered only from diverse printed and written records, or are carried in the memories of our senior townspeople. A 1954 Senior English class of F.H.S. has undertaken this project, and in the following pages, lie the results of investigation by members of this group. -

0017408.Pdf (13.13

THE INDUSTRIAL GEOGRAPHY OF THE KANAWHA VALLEY DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy In the Graduate School of The Ohio S tate U niversity By SELVA CARTER WILEY, B .A ., A.M. ***** The Ohio State University 1956 Approved byt — — A dviser Department of Geography 11 MAP I TOLL IRlQt KANAWHA VALLEY REGIONAL MAP tent lilt* tow TABLE OF CONTENTS PAQE INTRODUCTION.................... 1 A pproach ........... 2 Area of Study ....................................................................................................... U CHAPTER I - THE PHYSICAL LANDSCAPE .................................................................. 7 T e rra in .................................................................................................................... 7 Earth H istory ...................................................................................................... 11 CHAPTER I I - CLIMATE AND VEGETATION ............................................................. 17 C lim ate ..................................................................................................................... 17 Vegetation ........................................................................................................... 22 CHAPTER I I I - RESOURCES ......................................................................................... 26 C oal ......................................................................................................................... 26 Natural Gas -

Miller—Quarrier—Shrewsbury Dickinson—Dickenson Families

GENEALOGICAL NOTES OF THE Miller—Quarrier—Shrewsbury Dickinson—Dickenson Families AND THE LEWIS, RUFFNER, AND OTHER KINDRED BRANCHES WITH HISTORICAL INCIDENTS, ETC, dl C: GALLAHER, i-~ / a' CHARLESTON. AlANAWHA. WEST VA. I ir ^— , 1917 "THE SERVICE AND THE LOYALTY I OWE IN DOING IT PAYS ITSELF."—Macbeth 1-4. GENEALOGY. iSP"As these sketches were collected piece meal for several years any more recent and omitted births, deaths, etc., may be inserted by a descendant in his copy. The good Book indicates a blessing for those who honor the memory of their ancestors, and emphasizes the importance of not being neglect ful of family history. Nehemiah Chapter 7—verse 64—for an in stance in sacred history. Every family, as a rule, whether high or humble in the social scale, loves its own history and traditions handed down, while a prepared genealogy usually has a charming interest, provided, somebody devotes to its study and preparation his time and patient toil, sometimes, however, a thankless task, whose reward is a carping criticism by some, who would fain tear down that which they themselves could not, or at least do not, improve upon. Those lacking interest in family history or pride of ancestry can scarcely expect a succeeding generation to entertain it for them. In delving into a misty past, long after the actors have passed off the stage, entire accuracy in every detail can not be hoped for. FOREWORD. During a visit to my old home in Augusta County, Virginia, in 1908, I resolved to carry into execution a long cherished desire and promise to her, to make some reliable investigation into my wife's ancestors, upon her father's (the Miller) side, who came from Shenan doah County, Virginia, first to Mason County, and then to Kanawha, both at that time in Virginia, but now in West Virginia. -

Agricultural Education at the Tuskegee Normal and Industrial School

Journal of Agricultural Education Volume 48, Number 2, pp. 13 – 22 DOI: 10.5032/jae.2007.02013 AGRICULTURAL EDUCATION AT THE TUSKEGEE NORMAL AND INDUSTRIAL SCHOOL D. Barry Croom, Associate Professor North Carolina State University Abstract This study identified events during the life of Booker Taliaferro Washington and during the early years of the Tuskegee Normal and Industrial School that may have contributed to the development of agricultural and industrial education for African Americans. Washington’s experiences as a former slave and his observations of life for African Americans in the South in the late 1800’s may have shaped his philosophy of agricultural and industrial education. Washington believed that agricultural and industrial education contributed to the mental development of students, helped students secure the skills necessary to earn a living, and taught students the dignity of work. African American students wanted an education, but they often could not afford to attend school because they lacked the funds to pay tuition. The labor system and agricultural and industrial education provided the means by which they could labor for their education. It is concluded that Washington saw that the need for farmers, skilled artisans, and machinists was equally important to the academic preparation of lawyers, physicians, and professors. Agricultural and industrial education met this need. Under Washington’s leadership, Tuskegee Institute offered 37 industrial occupations on the campus and school farms. Introduction slavery and into citizenship, a task that proved extraordinarily difficult given the On July 4, 1881, a normal school for state of African American schools and African Americans opened its doors for the schooling during the late 1800’s. -

Ruffner Roots and Ramblings, Vol. 5, Iss. 3

Longwood University Digital Commons @ Longwood University Ruffner Roots & Ramblings Ruffner Family Association Collection, LU-163 9-2002 Ruffner Roots and Ramblings, Vol. 5, Iss. 3 Ruffner Ruffner Family Association Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.longwood.edu/ruffner_roots_ramblings Recommended Citation Ruffner, "Ruffner Roots and Ramblings, Vol. 5, Iss. 3" (2002). Ruffner Roots & Ramblings. 15. https://digitalcommons.longwood.edu/ruffner_roots_ramblings/15 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Ruffner Family Association Collection, LU-163 at Digital Commons @ Longwood University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Ruffner Roots & Ramblings by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Longwood University. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. RUFFNER ROOTS & RAMBLINGS Volume 5, Issue #3 September 2002 In Memoriam George Edward Ruffner September 17, 1925 - July 9, 2002 "A Great Tree has fallen in the forest of our family and the landscape will never again be the same." These words written by Bob Sheets in conveying the sad news of George Edward Ruffner's death are echoed by all Ruffner family members who came to know, love and admire this gallant and humane man . As Bob went on to say, "he has completed the journey of a great and giving life, whose inspiration will be forever implanted upon the soul of our Ruffner Family Association ." George, a proud descendent of Benjamin Ruffner, was the first child of Walter Ray and Theta Logan Ruffner. He was born in Effingham County, Illinois at the home of his great grandfather, Harrison Ruffner. After graduating from Effingham High George Edward Ruffner at Mason, School, he entered active service in the U.S. -

The Whole River Is a Bustle Some About Their Children, Brothers And

“…the whole river is a bustle some about their Children, Brothers and Husbands and the rest of us about our salt.” THE ANTEBELLUM INDUSTRIALIZATION OF THE KANAWHA VALLEY IN THE VIRGINIA BACKCOUNTRY A thesis presented to the faculty of the Graduate School of Western Carolina University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History. by Carter Bruns Director: Dr. Alexander Macaulay Associate Professor of History History Department Committee Members: Dr. Mary Ella Engel, History Dr. Jessica Swigger, History November 2013 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ABSTRACT ......................................................................................................................... i INTRODUCTION ...............................................................................................................6 Chapter 1: A Driving Vision for the Great Kanawha ........................................................20 Chapter 2: The Undaunted Pursuit of Salt .........................................................................41 Chapter 3: Relentless Innovation .......................................................................................64 Chapter 4: Bending Agricultural Slavery .......................................................................117 CONCLUSION ................................................................................................................143 BIBLIOGRAPHY ............................................................................................................153 -

A Comprehensive History of the West Virginia State Police, 1919-1979 By

A Comprehensive History of the West Virginia State Police, 1919-1979 by Merle T. Cole (Copyright, Merle T. Cole, 1998) Among state police departments [the West Virginia State Police] may, with its long and arduous experience, be regarded as a battle scarred veteran. It helped develop a new era of policing in the United States. Only three surviving departments preceded it. None faced greater obstacles. None have contributed more to the safety and well-being of the citizens whose lives and property it protects or to the strength and development of democracy within a state.--Col. H. Clare Hess, Superintendent, Department of Public Safety (West Virginia State Police) Twelfth Biennial Report (1940- 1942) NEW INTRODUCTION (1998) This is a minor rewrite of my original monograph, "Sixty Years of Service: A History of the West Virginia State Police, 1919-1979" (Copyright, 1979). I want to thank Sergeant Ric Robinson, Director of Media Relations, West Virginia State Police, for his support in the electronic publication of this study. -Merle T. Cole ORIGINAL INTRODUCTION (1979) This is a history of the origins and development of the West Virginia State Police (WVSP), the fourth oldest state police agency in America, now entering its 60th year of public service. My interest in the WVSP reached an early peak while I was a political science student at Marshall University. At the time, I could only manage to produce a limited study in the form of a term paper. Time and opportunity being more abundant recently, I have been able to complete a long-felt desire by producing this monograph. -

Ruffner Roots and Ramblings Catalog of Issues

Longwood University Digital Commons @ Longwood University Ruffner Roots & Ramblings Ruffner Family Association Collection LU-163 6-1-2002 Ruffner Roots and Ramblings Catalog of Issues Ruffner Family Association Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.longwood.edu/ruffner_roots_ramblings Recommended Citation Ruffner Family Association, "Ruffner Roots and Ramblings Catalog of Issues" (2002). Ruffner Roots & Ramblings. 3. https://digitalcommons.longwood.edu/ruffner_roots_ramblings/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Ruffner Family Association Collection LU-163 at Digital Commons @ Longwood University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Ruffner Roots & Ramblings by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Longwood University. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. R UFFN ER R OOTS & RAMBLINGS Catalog ot Issues June 1, 2002 i J - Ruffner Roots & Ramblings Catalog of Issues & Contents Table of Contents Issues/Contents Page 2 Index to Articles Page 4 Index to RFA Articles . • . Page 11 Know Your Board of Directors . Page 13 What Is It? Where Is It? Page 14 Family News Births . Page 15 Marriages . • . Page 16 Deaths . Page 17 RUFFNER ROOTS & RAMBLINGS ISSUES/CONTENTS Volume 1, Issue #1 . February 1998 Volume 2, Issue #3 ........... August 1999 Greetings from Organizing Board of Directors Sam McNeely Elected First President 1999 Reunion, Lancaster, Ohio 1999 Reunion Review Some Faced Bullets: She Handled Black Widows Message from the President Report from the Board of Directors Organizing Chairman's Final Report Review - 1997 Ruffner Reunion, Luray First Genealogy Workshop Held in Lancaster Westward Ho - On the Ruffner Trail to Ohio Report on the Charter Meeting The Family Forum - Luray Homestead Cemetery Restoration & Monuments McNeely Children Erect Fence at Monument Booker T.