Translation Today

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Investigation of a H Panachkkad PHC Area of Ko Kerala by Case Control

Research Article Investigation of a H epatitis A outbreak in Panachkkad PHC area of Kottayam district Kerala by case control design Areekal Binu 1* , Lawrence Tony 2, Antony Lal 3, M.J. Ajan 4, R. Ajith 5 {1Associate Professor, 4,5 Post Graduate Student }, Department of Community Medicine, Government Medical College, Kottayam, Kerala, INDIA. 2Assistant Professor, Department of Community Medicine, Government Medical College, Manjery, Kerala, INDIA. 3Assistant Surgeon, Panachikkad Block PHC, Kottayam District, Kerala, INDIA. Email: [email protected] Abstract Background : Viral Hepatitis (HAV) continues to be a major public health problem in India and is hyper -endemic for HAV infection . Early investigation of an epidemic of Hepatitis A will go a long way in containing the epidemic and preventing further transmission of the disease. Objectives : The objectives of the investigation were to descri be the epidemiological features of the Hepatitis A outbreak which occurred in PHC Panackikkad in November to December 2013, to find out the source of infection and suggest measures to control spread of the epidemic. Setting and Design : The setting was wards 5,7,18 and 19 of Panachikkad PHC, Kottayam District, Kerala State, India and the study was done using a case control design. Methods : The areas for investigation were identified in consultation with the PHC officials. For each case at least four to five household or neighbourhood controls were taken after matching for age. A total of 121 individuals were interviewed. All the cases and controls were interviewed at their home using a structured interview schedule which included informati on regarding the demographic characteristics, source of water, personal hygiene, and treatment of water before consumption, habit of consuming food from outside home and past history of Hepatitis Statistical Analysis : Data was entered in Microsoft excel an d was analysed using SPSS version 16.0. -

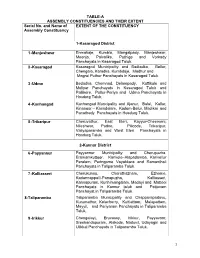

List of Lacs with Local Body Segments (PDF

TABLE-A ASSEMBLY CONSTITUENCIES AND THEIR EXTENT Serial No. and Name of EXTENT OF THE CONSTITUENCY Assembly Constituency 1-Kasaragod District 1 -Manjeshwar Enmakaje, Kumbla, Mangalpady, Manjeshwar, Meenja, Paivalike, Puthige and Vorkady Panchayats in Kasaragod Taluk. 2 -Kasaragod Kasaragod Municipality and Badiadka, Bellur, Chengala, Karadka, Kumbdaje, Madhur and Mogral Puthur Panchayats in Kasaragod Taluk. 3 -Udma Bedadka, Chemnad, Delampady, Kuttikole and Muliyar Panchayats in Kasaragod Taluk and Pallikere, Pullur-Periya and Udma Panchayats in Hosdurg Taluk. 4 -Kanhangad Kanhangad Muncipality and Ajanur, Balal, Kallar, Kinanoor – Karindalam, Kodom-Belur, Madikai and Panathady Panchayats in Hosdurg Taluk. 5 -Trikaripur Cheruvathur, East Eleri, Kayyur-Cheemeni, Nileshwar, Padne, Pilicode, Trikaripur, Valiyaparamba and West Eleri Panchayats in Hosdurg Taluk. 2-Kannur District 6 -Payyannur Payyannur Municipality and Cherupuzha, Eramamkuttoor, Kankole–Alapadamba, Karivellur Peralam, Peringome Vayakkara and Ramanthali Panchayats in Taliparamba Taluk. 7 -Kalliasseri Cherukunnu, Cheruthazham, Ezhome, Kadannappalli-Panapuzha, Kalliasseri, Kannapuram, Kunhimangalam, Madayi and Mattool Panchayats in Kannur taluk and Pattuvam Panchayat in Taliparamba Taluk. 8-Taliparamba Taliparamba Municipality and Chapparapadavu, Kurumathur, Kolacherry, Kuttiattoor, Malapattam, Mayyil, and Pariyaram Panchayats in Taliparamba Taluk. 9 -Irikkur Chengalayi, Eruvassy, Irikkur, Payyavoor, Sreekandapuram, Alakode, Naduvil, Udayagiri and Ulikkal Panchayats in Taliparamba -

Representation of Transgender Identities in Malayalam Literature

International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Invention (IJHSSI) ISSN (Online): 2319 – 7722, ISSN (Print): 2319 – 7714 www.ijhssi.org ||Volume 10 Issue 2 Ser. I || February 2021 || PP 40-42 Trapped Bodies: Representation of Transgender Identities in Malayalam Literature Lalini M. ABSTRACT The transgender community is a highly marginalised and vulnerable one and is seriously lagging behind on human development. The early society of Kerala will not accept a third gender. In the world literature transgenders became a significant branch of study has occurred .This article mainly focused on how Malayalam short stories presents transgender in the world of literature.. KEY WORDS: Transgender, Malayalam Literature, Gender roles,Identities --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Date of Submission: 25-01-2021 Date of Acceptance: 09-02-2021 --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- I. INTRODUCTION Human society is a complex organisation of human role relationships. The implication of such a structural conception is that the human beings act and interact with each other in accordance with the role they play. Their role performance in relation to each other is further conditioned by the status they occupy. The most basic criterion of defining status and a corresponding role for any individual in any society has been sex. Accordingly, men have been assigned certain specific type of roles to perform and women certain other. Sometimes, the society expects both men and women to discharge some roles jointly or interchangeably .Such and many other type similar situations present a general case of role performance and, therefore do not become an object of curiosity for people in society. This way, the individuals continue to act and interact with each other in accordance with the patterned and institutionalised frame work of role relationship in the society. -

Masculinity and the Structuring of the Public Domain in Kerala: a History of the Contemporary

MASCULINITY AND THE STRUCTURING OF THE PUBLIC DOMAIN IN KERALA: A HISTORY OF THE CONTEMPORARY Ph. D. Thesis submitted to MANIPAL ACADEMY OF HIGHER EDUCATION (MAHE – Deemed University) RATHEESH RADHAKRISHNAN CENTRE FOR THE STUDY OF CULTURE AND SOCIETY (Affiliated to MAHE- Deemed University) BANGALORE- 560011 JULY 2006 To my parents KM Rajalakshmy and M Radhakrishnan For the spirit of reason and freedom I was introduced to… This work is dedicated…. The object was to learn to what extent the effort to think one’s own history can free thought from what it silently thinks, so enable it to think differently. Michel Foucault. 1985/1990. The Use of Pleasure: The History of Sexuality Vol. II, trans. Robert Hurley. New York: Vintage: 9. … in order to problematise our inherited categories and perspectives on gender meanings, might not men’s experiences of gender – in relation to themselves, their bodies, to socially constructed representations, and to others (men and women) – be a potentially subversive way to begin? […]. Of course the risks are very high, namely, of being misunderstood both by the common sense of the dominant order and by a politically correct feminism. But, then, welcome to the margins! Mary E. John. 2002. “Responses”. From the Margins (February 2002): 247. The peacock has his plumes The cock his comb The lion his mane And the man his moustache. Tell me O Evolution! Is masculinity Only clothes and ornaments That in time becomes the body? PN Gopikrishnan. 2003. “Parayu Parinaamame!” (Tell me O Evolution!). Reprinted in Madiyanmarude Manifesto (Manifesto of the Lazy, 2006). Thrissur: Current Books: 78. -

Colonial Rule in Kerala and the Development of Malayalam Novels: Special Reference to the Early Malayalam Novels

RESEARCH REVIEW International Journal of Multidisciplinary 2021; 6(2):01-03 Research Paper ISSN: 2455-3085 (Online) https://doi.org/10.31305/rrijm.2021.v06.i02.001 Double Blind Peer Reviewed/Refereed Journal https://www.rrjournals.com/ Colonial Rule in Kerala and the Development of Malayalam Novels: Special Reference to the Early Malayalam Novels *Ramdas V H Research Scholar, Comparative Literature and Linguistics, Sree Sankaracharya University of Sanskrit, Kalady ABSTRACT Article Publication Malayalam literature has a predominant position among other literatures. From the Published Online: 14-Feb-2021 ‘Pattu’ moments it had undergone so many movements and theories to transform to the present style. The history of Malayalam literature witnessed some important Author's Correspondence changes and movements in the history. That means from the beginning to the present Ramdas V H situation, the literary works and literary movements and its changes helped the development of Malayalam literature. It is difficult to estimate the development Research Scholar, Comparative Literature periods of Malayalam literature. Because South Indian languages like Tamil, and Linguistics, Sree Sankaracharya Kannada, etc. gave their own contributions to the development of Malayalam University of Sanskrit, Kalady literature. Especially Tamil literature gave more important contributions to the Asst.Professor, Dept. of English development of Malayalam literature. The English education was another milestone Ilahia College of Arts and Science of the development of Malayalam literature. The establishment of printing presses, ramuvh[at]gmail.com the education minutes of Lord Macaulay, etc. helped the development process. People with the influence of English language and literature, began to produce a new style of writing in Malayalam literature. -

Accused Persons Arrested in Kottayam District from 26.01.2020To01.02.2020

Accused Persons arrested in Kottayam district from 26.01.2020to01.02.2020 Name of Name of the Name of the Place at Date & Arresting Court at Sl. Name of the Age & Cr. No & Sec Police father of Address of Accused which Time of Officer, which No. Accused Sex of Law Station Accused Arrested Arrest Rank & accused Designation produced 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 ANOOP BHAVAN, Cr. No. 142/20 ALTHARAVILAKOM KSRTC KOTTAYAM Bail form 1 ANILKUMAR N NELSON G 46 26.01.20 U/S 279 IPC & SABU SUNNY KARA, ARAYOOR P O, BHAGOM WEST PS Police Station 00:45 Hrs 185 MV Act. TVM KURUMUTTOM HOUSE, BYPASS Cr. No. 143/20 SHIJU K THIRUVATHUK KOTTAYAM Bail form 2 JOHNSON 37 BHAGOM, VELOOR 26.01.20 U/S 279 IPC & SATHY P R JOHNSON AL WEST PS Police Station KARA, VELOOR 04:45 Hrs 185 MV Act. VILLAGE. PAIVALLIKKAL HOUSE, Cr. No. 144/20 AIDA JN, KODIMATHA KOTTAYAM Bail form 3 AJAYAKUMAR RAJAN 42 KARAPUZHA 26.01.20 U/S 279 IPC & SATHY P R KARA, KOTTAYAM WEST PS Police Station 05:30 Hrs 185 MV Act. VILLAGE. PUTHETTU HOUSE, Cr. No. 147/20 DEVASIA PADY THEKKUM KOTTAYAM Bail form 4 SOBIN JOSEPH JOSEPH 33 27.01.20 U/S 279 IPC & SABU SUNNY BHAGOM, VELOOR GOPURAM WEST PS Police Station 08:40 Hrs 185 MV Act. KARA. VALIYA VEETTIL Cr. No. 148/20 HOUSE, AYYAPPA THEKKUM KOTTAYAM Bail form 5 FEBIN SCARIA SCARIA 37 27.01.20 U/S 279 IPC & SABU SUNNY TEMPLE BHAGOM, GOPURAM WEST PS Police Station 09:35 Hrs 185 MV Act. -

An Analysis of Selected Works from Contemporary Malayalam Dalit Poetry Pambirikunnu, V

NavaJyoti, International Journal of Multi-Disciplinary Research Volume 1, Issue 1, August 2016 Resisting Discriminations: An Analysis of Selected works from Contemporary Malayalam Dalit Poetry Reshma K 1 Assistant Professor, Dept. of English, St. Aloysius College, Elthuruth, India ABSTRACT Dalit Sahitya has a voice of anguish and anger. It protests against social injustice, inequality, cruelty and economic exploitation based on caste and class. The primary motive of Dalit literature, especially poetry, is the liberation of Dalits. This paper focuses on contemporary Dalit poets in Malayalam, Raghavan Atholi, S. Joseph and G. Sashi Madhuraveli, who use their poetry to resist, in a variety of ways their continuing marginalization and discrimination. The poems are a bitter comment on predicament of the Dalits who still live in poverty, hunger, the problems of their colour, race, social status and their names. Keywords: Dalit poetry, resistance, contemporary Malayalam poetry, contemporary Dalit literature Dalit is described as members of scheduled castes and tribes, neo-Buddhists, the working people, landless and poor peasants, women and all those who are exploited politically, economically and in the name of religion (Omvedt 72). B. R. Ambedkar was one of the first leaders who strived for these counter hegemonic groups. He was the first Dalit to obtain a college education in India. All his struggles helped Dalits to come forward. He raised his voice to eradicate untouchability, caste discrimination, non-class type oppressions and women oppressions. All these ‘Ambedkarite’ thoughts formed a hope for the oppressed classes. These counter hegemonic groups resist through literature. Sentiments, hankers and the struggles of the suppressed is portrayed in Dalit literature. -

Kavi Vallathol: the Preserver of Art and Literature

International Journal of Sanskrit Research 2019; 5(1): 33-34 ISSN: 2394-7519 IJSR 2019; 5(1): 33-34 Mah¡kavi Vallathol: The preserver of art and literature © 2019 IJSR www.anantaajournal.com Received: 09-11-2018 Saraswathi Devi V Accepted: 14-12-2018 Saraswathi Devi V The life, literary and cultural activities of Vallathol Narayana Menon (1878-1958) form a Research Scholar, Dept. of distinct chapter in story of the evaluation of literature and culture in Kerala. Vallathol appeared Sanskrit Sahitya, SSUS, Kalady, on the literary science at a time when Modern Malayalam Poetry was in its infancy. Sanskrit Kerala, India norms in literary composition controlled the literary field, and poetry in Malayalam was only a shadow of what poetry in Sanskrit was. Himself nurtured in the Sanskrit tradition which his early compositions in the Sanskrit form. The poet in company with his two illustrious compeers Ullur and A¿an. Soon made Malayalam poetry with his well known lyrical piece in [1] Dravidian metre a thing of the Kerala Soil . Poetry in Malayalam soon ceased to be a Kerala off shoot of Sanskrit literature and developed with a new secular content and native idiom and [2] form . Vallathol entered to the world of literature through singing Sanskrit Muktakas. He has also written a few works in Sanskrit such as Mat¤viyoga in 21 verses, P¡rvatip¡d¡dike¿astava, K¤snastava and Tapatisamvara¸a. Triy¡ma and Saml¡papura written in collaboration with [3] Vell¡na¿¿ery V¡sunni Mussat . Vallathol was a prodigious writer and author of over eighty works of which ‘Citrayogam’ a mah¡k¡vya, Sahitya Manjari in 10 volumes. -

K. Satchidanandan

1 K. SATCHIDANANDAN Bio-data: Highlights Date of Birth : 28 May 1946 Place of birth : Pulloot, Trichur Dt., Kerala Academic Qualifications M.A. (English) Maharajas College, Ernakulam, Kerala Ph.D. (English) on Post-Structuralist Literary Theory, University of Calic Posts held Consultant, Ministry of Human Resource, Govt. of India( 2006-2007) Secretary, Sahitya Akademi, New Delhi (1996-2006) Editor (English), Sahitya Akademi, New Delhi (1992-96) Professor, Christ College, Irinjalakuda, Kerala (1979-92) Lecturer, Christ College, Irinjalakuda, Kerala (1970-79) Lecturer, K.K.T.M. College, Pullut, Trichur (Dt.), Kerala (1967-70) Present Address 7-C, Neethi Apartments, Plot No.84, I.P. Extension, Delhi 110 092 Phone :011- 22246240 (Res.), 09868232794 (M) E-mail: [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Other important positions held 1. Member, Faculty of Languages, Calicut University (1987-1993) 2. Member, Post-Graduate Board of Studies, University of Kerala (1987-1990) 3. Resource Person, Faculty Improvement Programme, University of Calicut, M.G. University, Kottayam, Ambedkar University, Aurangabad, Kerala University, Trivandrum, Lucknow University and Delhi University (1990-2004) 4. Jury Member, Kerala Govt. Film Award, 1990. 5. Member, Language Advisory Board (Malayalam), Sahitya Akademi (1988-92) 6. Member, Malayalam Advisory Board, National Book Trust (1996- ) 7. Jury Member, Kabir Samman, M.P. Govt. (1990, 1994, 1996) 8. Executive Member, Progressive Writers’ & Artists Association, Kerala (1990-92) 9. Founder Member, Forum for Secular Culture, Kerala 10. Co-ordinator, Indian Writers’ Delegation to the Festival of India in China, 1994. 11. Co-ordinator, Kavita-93, All India Poets’ Meet, New Delhi. 12. Adviser, ‘Vagarth’ Poetry Centre, Bharat Bhavan, Bhopal. -

World History Bulletin Fall 2016 Vol XXXII No

World History Bulletin Fall 2016 Vol XXXII No. 2 World History Association Denis Gainty Editor [email protected] Editor’s Note From the Executive Director 1 Letter from the President 2 Special Section: The World and The Sea Introduction: The Sea in World History 4 Michael Laver (Rochester Institute of Technology) From World War to World Law: Elisabeth Mann Borgese and the Law of the Sea 5 Richard Samuel Deese (Boston University) The Spanish Empire and the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans: Imperial Highways in a Polycentric Monarchy 9 Eva Maria Mehl (University of North Carolina Wilmington) Restoring Seas 14 Malcolm Campbell (University of Auckland) Ship Symbolism in the ‘Arabic Cosmopolis’: Reading Kunjayin Musliyar’s “Kappapattu” in 18th Century Malabar 17 Shaheen Kelachan Thodika (Jawaharlal Nehru University) The Panopticon Comes Full Circle? 25 Sarah Schneewind (University of California San Diego) Book Review 29 Abeer Saha (University of Virginia) practical ideas for the classroom; she intro- duces her course on French colonialism in Domesticating the “Queen of Haiti, Algeria, and Vietnam, and explains how Beans”: How Old Regime France aseemingly esoteric topic like the French empirecan appear profoundly relevant to stu- Learned to Love Coffee* dents in Southern California. Michael G. Vann’sessay turns our attention to the twenti- Julia Landweber eth century and to Indochina. He argues that Montclair State University both French historians and world historians would benefit from agreater attention to Many goods which students today think of Vietnamese history,and that this history is an as quintessentially European or “Western” ideal means for teaching students about cru- began commercial life in Africa and Asia. -

MA Syllbus 2014 Revised 17 8 14

SYLLABUS FOR M.A. PROGRAMME IN SANSKRIT SAHITYA (2014 June onwards) The syllabus of M.A. programme in Sanskrit Sahitya (Course Credit and Semester System) is being restructured in order to satisfy the contemporary requirements on the basis of the recent developments in the academic field. To provide an interdisciplinary nature to the courses, some areas of studies are developed, changed and/or redefined. M.A. programme is consisted of four semesters. Total number of courses is 20. Each course is having 4 credits. Thus the student has to acquire a minimum total of 80 credits for completing the programme. Among the 20 courses of the PG programme, 7 are electives/optionals out of which 5 should be from the parent department(Internal Electives) and the remaining two must be, from any other departments(multidisciplinary electives). There will be five courses in each semester and five hours are distributred for each course. There will be 3 core courses and two elective/optional course in each semester. In the first and fourth semesters, elective/optional courses are to be taken from within the parent department from the internal electives given in the list and in the second and third, it has to be from other departments. Students of other departments can opt the multidisciplinary elective courses offerd by the Department of Sanskrit Sahitya in the second and third semesters and the students may write answers either in Sanskrit, or in English or in Malayalam The Course 20, ie, ProjectCourse No:1 (Dissertation) will be in the form of the presentation of seminar and a project work done by each and every student. -

The Making of Modern Malayalam Prose and Fiction: Translations from European Languages Into Malayalam in the First Half of the Twentieth Century

The Making of Modern Malayalam Prose and Fiction: Translations from European Languages into Malayalam in the First Half of the Twentieth Century K.M. Sherrif Abstract Translations from European languages have played a crucial role in the evolution of Malayalam prose and fiction in the first half of the Twentieth Century. Many of them are directly linked to the socio- political movements in Kerala which have been collectively designated ‘Kerala’s Renaissance.’ The nature of the translated texts reveal the operation of ideological and aesthetic filters in the interface between literatures, while the overwhelming presence of secondary translations indicate the hegemonic status of English as a receptor language. The translations never occupied a central position in the Malayalam literature and served mostly as mere literary and political stimulants. Keywords: Translation - evolution of genres, canon - political intervention The role of translation in the development of languages and literatures has been extensively discussed by translation scholars in the West during the last quarter of a century. The proliferation of diachronic translation studies that accompanied the revolutionary breakthroughs in translation theory in the mid-Eighties of the Twentieth Century resulted in the extensive mapping of the intervention of translation in the development of discourses and shifts of ideological paradigms in cultures, in the development of genres and the construction and disruption of the canon in literatures and in altering the idiomatic and structural paradigms of languages. One of the most detailed studies in the area was made by Andre Lefevere (1988, pp 75-114) Lefevere showed with convincing 118 Translation Today K.M.