Lost in a Transmedia Universe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nomination Press Release

Elisabeth Moss as Peggy Olson Outstanding Lead Actor In A Drama Series Nashville • ABC • ABC Studios Connie Britton as Rayna James Breaking Bad • AMC • Sony Pictures Television Scandal • ABC • ABC Studios Bryan Cranston as Walter White Kerry Washington as Olivia Pope Downton Abbey • PBS • A Carnival / Masterpiece Co-Production Hugh Bonneville as Robert, Earl of Grantham Outstanding Lead Actor In A Homeland • Showtime • Showtime Presents, Miniseries Or A Movie Teakwood Lane Productions, Cherry Pie Behind The Candelabra • HBO • Jerry Productions, Keshet, Fox 21 Weintraub Productions in association with Damian Lewis as Nicholas Brody HBO Films House Of Cards • Netflix • Michael Douglas as Liberace Donen/Fincher/Roth and Trigger Street Behind The Candelabra • HBO • Jerry Productions, Inc. in association with Media Weintraub Productions in association with Rights Capital for Netflix HBO Films Kevin Spacey as Francis Underwood Matt Damon as Scott Thorson Mad Men • AMC • Lionsgate Television The Girl • HBO • Warner Bros. Jon Hamm as Don Draper Entertainment, GmbH/Moonlighting and BBC in association with HBO Films and Wall to The Newsroom • HBO • HBO Entertainment Wall Media Jeff Daniels as Will McAvoy Toby Jones as Alfred Hitchcock Parade's End • HBO • A Mammoth Screen Production, Trademark Films, BBC Outstanding Lead Actress In A Worldwide and Lookout Point in association Drama Series with HBO Miniseries and the BBC Benedict Cumberbatch as Christopher Tietjens Bates Motel • A&E • Universal Television, Carlton Cuse Productions and Kerry Ehrin -

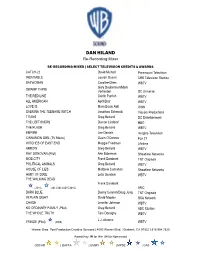

DAN HILAND Re-Recording Mixer

DAN HILAND Re-Recording Mixer RE-RECORDING MIXER | SELECT TELEVISION CREDITS & AWARDS CATCH-22 David Michod Paramount Television INSATIABLE Lauren Gussis CBS Television Studios BATWOMAN Caroline Dries WBTV Gary Dauberman/Mark SWAMP THING Verheiden DC Universe THE RED LINE Cairlin Parrish WBTV ALL AMERICAN April Blair WBTV LOVE IS Mara Brock Akil OWN SABRINA THE TEENAGE WITCH Jonathan Schmock Viacom Productions TITANS Greg Berlanti DC Entertainment THE LEFTOVERS Damon Lindelof HBO THE FLASH Greg Berlanti WBTV EMPIRE Lee Daniels Imagine Television CINNAMON GIRL (TV Movie) Gavin O'Connor Fox 21 WITCHES OF EAST END Maggie Friedman Lifetime ARROW Greg Berlanti WBTV RAY DONOVAN (Pilot) Ann Biderman Showtime Networks MOB CITY Frank Darabont TNT Originals POLITICAL ANIMALS Greg Berlanti WBTV HOUSE OF LIES Matthew Carnahan Showtime Networks HART OF DIXIE Leila Gerstein WBTV THE WALKING DEAD Frank Darabont (2010) (2012/2014/2015/2016) AMC DARK BLUE Danny Cannon/Doug Jung TNT Originals IN PLAIN SIGHT David Maples USA Network CHASE Jennifer Johnson WBTV NO ORDINARY FAMILY (Pilot) Greg Berlanti ABC Studios THE WHOLE TRUTH Tom Donaghy WBTV J.J. Abrams FRINGE (Pilot) (2009) WBTV Warner Bros. Post Production Creative Services | 4000 Warner Blvd. | Burbank, CA 91522 | 818.954.7825 Award Key: W for Win | N for Nominated OSCAR | BAFTA | EMMY | MPSE | CAS LIMELIGHT (Pilot) David Semel, WBTV HUMAN TARGET Jonathan E. Steinberg WBTV EASTWICK Maggie Friedman WBTV V (Pilot) Kenneth Johnson WBTV TERMINATOR: THE SARAH CONNER Josh Friedman CHRONICLES WBTV CAPTAIN -

SAG/AFTRA FILM (Partial List) Scare Package Supporting/ “Officer Ragen” Paper Street Pictures/ Aaron B. Koontz Dir. Human Pl

SAG/AFTRA FILM (Partial List) Scare Package Supporting/ “Officer Ragen” Paper Street Pictures/ Aaron B. Koontz Dir. Human Play Lead/ “James” Paper Street Pictures/ Mathieu Ricordi Dir. Little Woods Supporting/ "Man" Buffalo Picture House/ Nia DaCosta Dir. Elephone Man Lead/ "Bobby" Global Films/ Magarditch Halvadjian Dir. The Cable Men Starring/ "Barney" McShane Films/ Robin Conly Dir. Bitch (Short) Supporting/ "Will" Edgen Films/ Robin Conly Dir. Small Packages (Short) Starring/ "Porter" Grade A Films/ Anthony Faust Dir. An American In Texas Lead/ "Earl Doonan" Film Exchange/ Anthony Pedone Dir. Overcast (Short) Lead/ "Paulie" Atomic Productions/ Ben Adams Dir. Bomb City Supporting/ "Officer Chuck" 3rd Identity Films/ Jamie Brooks Dir. As Far As The Eye Can See Supporting/ "Bob Tanner" AFATECS LLC/ David Franklin Dir. Entity Starring/ "Eugene" Screengage LLC/ Michael Yurinko Dir. Human Play Lead/ "James" Paper Street Pictures/ Mathieu Ricordi Dir. Hard Reset 3-D Lead/ "Det. Wright" Buk Films/ Deepak Chetty Dir. The Doo Dah Man Supporting/ "Frank" Flatiron Pictures/ Claude Green Dir. Adventures of Pepper and Paula Lead/ "Ricky" The Nations/ Kevin & Robin Nations Dir. Sin City 2 Supporting/ "Tourist" Troublemaker/ Robert Rodriguez Dir. TELEVISION The Pact (Mini Series) Lead/ ”Drummer” Katara Studios/ Michael Phillips EP. Three Knee Deep (Mini Series) Lead/ "Jack" Luna/Luca Bercovichi Dir. The Leftovers Recurring/ "Sam" HBO/ Damon Lindelof EP. Queen of the South Co-Star/ "Donald Henry" USA/ Matthew Penn EP. From Dusk Til Dawn Co-Star/ "Chester" El Rey/ Eduardo Sanchez Dir. In An Instant Starring/ "Pete Soulis" ABC/ Todd Cobery Dir. American Crime Co-Star/ "Patrol Officer" ABC/ John Ridley Dir. -

L'équipe Des Scénaristes De Lost Comme Un Auteur Pluriel Ou Quelques Propositions Méthodologiques Pour Analyser L'auctorialité Des Séries Télévisées

Lost in serial television authorship : l’équipe des scénaristes de Lost comme un auteur pluriel ou quelques propositions méthodologiques pour analyser l’auctorialité des séries télévisées Quentin Fischer To cite this version: Quentin Fischer. Lost in serial television authorship : l’équipe des scénaristes de Lost comme un auteur pluriel ou quelques propositions méthodologiques pour analyser l’auctorialité des séries télévisées. Sciences de l’Homme et Société. 2017. dumas-02368575 HAL Id: dumas-02368575 https://dumas.ccsd.cnrs.fr/dumas-02368575 Submitted on 18 Nov 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution - NonCommercial - NoDerivatives| 4.0 International License UNIVERSITÉ RENNES 2 Master Recherche ELECTRA – CELLAM Lost in serial television authorship : L'équipe des scénaristes de Lost comme un auteur pluriel ou quelques propositions méthodologiques pour analyser l'auctorialité des séries télévisées Mémoire de Recherche Discipline : Littératures comparées Présenté et soutenu par Quentin FISCHER en septembre 2017 Directeurs de recherche : Jean Cléder et Charline Pluvinet 1 « Créer une série, c'est d'abord imaginer son histoire, se réunir avec des auteurs, la coucher sur le papier. Puis accepter de lâcher prise, de la laisser vivre une deuxième vie. -

February 26, 2021 Amazon Warehouse Workers In

February 26, 2021 Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer, Alabama are voting to form a union with the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union (RWDSU). We are the writers of feature films and television series. All of our work is done under union contracts whether it appears on Amazon Prime, a different streaming service, or a television network. Unions protect workers with essential rights and benefits. Most importantly, a union gives employees a seat at the table to negotiate fair pay, scheduling and more workplace policies. Deadline Amazon accepts unions for entertainment workers, and we believe warehouse workers deserve the same respect in the workplace. We strongly urge all Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer to VOTE UNION YES. In solidarity and support, Megan Abbott (DARE ME) Chris Abbott (LITTLE HOUSE ON THE PRAIRIE; CAGNEY AND LACEY; MAGNUM, PI; HIGH SIERRA SEARCH AND RESCUE; DR. QUINN, MEDICINE WOMAN; LEGACY; DIAGNOSIS, MURDER; BOLD AND THE BEAUTIFUL; YOUNG AND THE RESTLESS) Melanie Abdoun (BLACK MOVIE AWARDS; BET ABFF HONORS) John Aboud (HOME ECONOMICS; CLOSE ENOUGH; A FUTILE AND STUPID GESTURE; CHILDRENS HOSPITAL; PENGUINS OF MADAGASCAR; LEVERAGE) Jay Abramowitz (FULL HOUSE; GROWING PAINS; THE HOGAN FAMILY; THE PARKERS) David Abramowitz (HIGHLANDER; MACGYVER; CAGNEY AND LACEY; BUCK JAMES; JAKE AND THE FAT MAN; SPENSER FOR HIRE) Gayle Abrams (FRASIER; GILMORE GIRLS) 1 of 72 Jessica Abrams (WATCH OVER ME; PROFILER; KNOCKING ON DOORS) Kristen Acimovic (THE OPPOSITION WITH JORDAN KLEPPER) Nick Adams (NEW GIRL; BOJACK HORSEMAN; -

COVID Chronicle by Karen Wilkin

Art September 2020 COVID chronicle by Karen Wilkin On artists in lockdown. ’ve been asking many artists—some with significant track records, some aspiring, some I students—about the effect of the changed world we’ve been living in since mid-March. The responses have been both negative and positive, sometimes at the same time. People complain of too much solitude or not enough, of the luxury of more studio time or the stress of distance from the workspace or—worst case—of having lost it. There’s the challenge of not having one’s usual materials and the freedom to improvise out of necessity, the lack of interruption and the frustration of losing direct contact with peers and colleagues, and more. The drastic alterations in our usual habits over the past months have had sometimes dramatic, sometimes subtle repercussions in everyone’s work. Painters in oil are using watercolor, drawing, or experimenting with collage; makers of large-scale paintings are doing small pictures on the kitchen table. Ophir Agassi, an inventive painter of ambiguous narratives, has been incising drawings in mud, outdoors, with his young daughters. People complain of too much solitude or not enough, of the luxury of more studio time or the stress of distance from the workspace or—worst case—of having lost it. Many of the artists I’ve informally polled have had long-anticipated, carefully planned exhibitions postponed or canceled. In partial compensation, a wealth of online exhibitions and special features has appeared since mid-March, despite the obvious shortcomings of seeing paintings and sculptures on screen instead of experiencing their true size, surface, color, and all the rest of it. -

In Teaching and Learning JOURNAL

CurrentsACADEMIC In Teaching and Learning JOURNAL VOLUME 11 NUMBER 2 FEBRUARY 2020 CURRENTS | FEBRUARY 2020 About Us Currents in Teaching and Learning is a peer-reviewed electronic journal that fosters exchanges among reflective teacher-scholars across the disciplines. Published twice a year, Currents seeks to improve teaching and learning in higher education with short reports on classroom practices as well as longer research, theoretical, or conceptual articles and explorations of issues and challenges facing teachers today. Non-specialist and jargon-free, Currents is addressed to both faculty and graduate students in higher education, teaching in all academic disciplines. Subscriptions If you wish to be notified when each new issue of Currents becomes available online and to receive our Calls for Submissions and other announcements, please join our Currents Subscribers’ Listserv. Subscribe Here Table of Contents EDITORIAL TEACHING REPORTS “Globalizing Learning” 4 “ Reimagining Epistemologies: Librarian- 16 —Martin Fromm Faculty Collaboration to Integrate Critical Information Literacy into Spanish Community-Based Learning” —Joanna Bartow and Pamela Mann PROGRAM REPORTS “ Encountering Freire: An International 7 “Bringing the Diary into the Classroom: 47 Partnership in Experiential Learning and Ongoing Diary, Journal, and Notebook Social Justice” Project” —Allyson Eamer and Anna Rodrigues —Angela Hooks “Transnational Exposure, Exchange, 32 and Reflection: Globalizing Writing Pedagogy” ESSAY —Denise Comer and Anannya Dasgupta “Engaging University Faculty in 94 Linguistically Responsive Instruction: Challenges and Opportunities” “Changing Our Minds: Blending 55 —Colleen Gallagher and Jennifer Haan Transnational, Integrative, and Service- Oriented Pedagogies in Pursuit of Transformative Education” —Nikki K. Rizzo and David W. Marlow BOOK REVIEWS David Damrosch’s How to Read World 108 “ Globalized Learning Through Service: 67 Literature Study Abroad and Service Learning” —Brandon W. -

ENGLISH 2810: Television As Literature (V

ENGLISH 2810: Television as Literature (v. 1.0) 9:00 – 10:15 T/Th | EH 229 Dr. Scott Rogers | [email protected] | EH 448 http://faculty.weber.edu/srogers The Course The average American watches about 5 hours of television a day. We are told that this is bad. We are told that television is bad for us, that it is bad for our families, and that it is wasting our time. But not all television is that way. Some television shows have what we might call “literary pretensions.” Shows such as Twin Peaks, Homicide: Life on the Street, The Wire, Buffy the Vampire Slayer, Firefly, Veronica Mars, Battlestar Galactica, and LOST have been both critically acclaimed and the subject of much academic study. In this course, we shall examine a select few of these shows, watching complete seasons as if they were self-contained literary texts. In other words, in this course, you will watch TV and get credit for it. You will also learn to view television in an active and critical fashion, paying attention to the standard literary techniques (e.g. character, theme, symbol, plot) as well as televisual issues such as lighting, music, and camerawork. Texts Students will be expected to own, or have access to, the following: Firefly ($18 on amazon.com; free on hulu.com) and Serenity ($4 used on amazon.com) LOST season one ($25 on amazon.com; free on hulu.com or abc.com) Battlestar Galactica season one ($30 on amazon.com) It is in your best interest to buy or borrow these, if only to make it easier for you to go back and re-watch episodes for your assignments. -

Treball De Fi De Grau Títol

Facultat de Ciències de la Comunicació Treball de fi de grau Títol Autor/a Tutor/a Departament Grau Tipus de TFG Data Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona Facultat de Ciències de la Comunicació Full resum del TFG Títol del Treball Fi de Grau: Català: Castellà: Anglès: Autor/a: Tutor/a: Curs: Grau: Paraules clau (mínim 3) Català: Castellà: Anglès: Resum del Treball Fi de Grau (extensió màxima 100 paraules) Català: Castellà: Anglès: Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona Índice 1. INTRODUCCIÓN ...................................................................................................... 2 Motivación personal: ............................................................................................. 2 2. MARCO TEÓRICO ................................................................................................... 3 2.1 BAD ROBOT ....................................................................................................... 3 2.2 JEFFREY JACOB ABRAMS ............................................................................... 5 2.3 BAD ROBOT: PRODUCCIONES CINEMATOGRÁFICAS Y SELLO PROPIO .... 7 3. METODOLOGÍA ..................................................................................................... 10 4. INVESTIGACIÓN DE CAMPO ................................................................................ 13 4.1 UNA NARRATIVA AUDIOVISUAL ÚNICA ........................................................ 13 4.1.1 PARTÍCULAS NARRATIVAS ......................................................................... 13 4.1.1.1 -

Defining the Digital Services Landscape for the Middle East

Defining the Digital Services landscape for the Middle East Defining the Digital Services landscape for the Middle East 1 2 Contents Defining the Digital Services landscape for the Middle East 4 The Digital Services landscape 6 Consumer needs landscape Digital Services landscape Digital ecosystem Digital capital Digital Services Maturity Cycle: Middle East 24 Investing in Digital Services in the Middle East 26 Defining the Digital Services landscape for the Middle East 3 Defining the Digital Services landscape for the Middle East The Middle East is one of the fastest growing emerging markets in the world. As the region becomes more digitally connected, demand for Digital Services and technologies is also becoming more prominent. With the digital economy still in its infancy, it is unclear which global advances in Digital Services and technologies will be adopted by the Middle East and which require local development. In this context, identifying how, where and with whom to work with in this market can be very challenging. In our effort to broaden the discussion, we have prepared this report to define the Digital Services landscape for the Middle East, to help the region’s digital community in understanding and navigating through this complex and ever-changing space. Eng. Ayman Al Bannaw Today, we are witnessing an unprecedented change in the technology, media, and Chairman & CEO telecommunications industries. These changes, driven mainly by consumers, are taking Noortel place at a pace that is causing confusion, disruption and forcing convergence. This has created massive opportunities for Digital Services in the region, which has in turn led to certain industry players entering the space in an incoherent manner, for fear of losing their market share or missing the opportunities at hand. -

The Expression of Orientations in Time and Space With

The Expression of Orientations in Time and Space with Flashbacks and Flash-forwards in the Series "Lost" Promotor: Auteur: Prof. Dr. S. Slembrouck Olga Berendeeva Master in de Taal- en Letterkunde Afstudeerrichting: Master Engels Academiejaar 2008-2009 2e examenperiode For My Parents Who are so far But always so close to me Мои родителям, Которые так далеко, Но всегда рядом ii Acknowledgments First of all, I would like to thank Professor Dr. Stefaan Slembrouck for his interest in my work. I am grateful for all the encouragement, help and ideas he gave me throughout the writing. He was the one who helped me to figure out the subject of my work which I am especially thankful for as it has been such a pleasure working on it! Secondly, I want to thank my boyfriend Patrick who shared enthusiasm for my subject, inspired me, and always encouraged me to keep up even when my mood was down. Also my friend Sarah who gave me a feedback on my thesis was a very big help and I am grateful. A special thank you goes to my parents who always believed in me and supported me. Thanks to all the teachers and professors who provided me with the necessary baggage of knowledge which I will now proudly carry through life. iii Foreword In my previous research paper I wrote about film discourse, thus, this time I wanted to continue with it but have something new, some kind of challenge which would interest me. After a conversation with my thesis guide, Professor Slembrouck, we decided to stick on to film discourse but to expand it. -

Copyrighted Material

PART ON E F IS FOR FORTUNE COPYRIGHTED MATERIAL CCH001.inddH001.indd 7 99/18/10/18/10 77:13:28:13:28 AAMM CCH001.inddH001.indd 8 99/18/10/18/10 77:13:28:13:28 AAMM LOST IN LOST ’ S TIMES Richard Davies Lost and Losties have a pretty bad reputation: they seem to get too much fun out of telling and talking about stories that everyone else fi nds just irritating. Even the Onion treats us like a bunch of fanatics. Is this fair? I want to argue that it isn ’ t. Even if there are serious problems with some of the plot devices that Lost makes use of, these needn ’ t spoil the enjoyment of anyone who fi nds the series fascinating. Losing the Plot After airing only a few episodes of the third season of Lost in late 2007, the Italian TV channel Rai Due canceled the show. Apparently, ratings were falling because viewers were having diffi culty following the plot. Rai Due eventually resumed broadcasting, but only after airing The Lost Survivor Guide , which recounts the key moments of the fi rst two seasons and gives a bit of background on the making of the series. Even though I was an enthusiastic Lostie from the start, I was grateful for the Guide , if only because it reassured me 9 CCH001.inddH001.indd 9 99/18/10/18/10 77:13:28:13:28 AAMM 10 RICHARD DAVIES that I wasn’ t the only one having trouble keeping track of who was who and who had done what.