Joint Planning & Architectural Commission

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 55 Zoning Code Revision

TABLE OF SELECTED CONTENTS Page No. ARTICLE 1 TITLE; LEGISLATIVE FINDINGS; DECLARATION OF PURPOSE................ 1 ARTICLE 2 WORD USAGE AND DEFINITIONS............ 4 ARTICLE 3 DISTRICTS; BOUNDARIES................. 23 ARTICLE 4 R-20 ONE-FAMILY RESIDENCE DISTRICT.... 23 § 55-4.1 - Intent.................... 23 § 55-4.2 - Permitted and Special Exception Uses........................ 24 § 55-4.3 - Dimensional Regulations... 24 ARTICLE 5 RM RESORT MOTEL DISTRICT.............. 24 § 55-5.1 - Intent.................... 24 § 55-5.2 - Permitted and Special Exception Uses........................ 24 § 55-5.3 - Dimensional Regulations... 24 § 55-5.4 - Resort Motel Standards.... 25 § 55-5.5 - Resort Motel Accessory Uses.................................. 25 § 55-5.6 - Resort Motel Minimum Landscaped Area....................... 25 ARTICLE 6 VB VILLAGE BUSINESS DISTRICT.......... 26 § 55-6.1 - Intent.................... 26 § 55-6.2 - Permitted and Special Exception Uses........................ 26 § 55-6.3 - Dimensional Regulations... 26 § 55-6.4 - VB District Special Conditions............................ 26 i Page No. ARTICLE 7 OD OFFICE DISTRICT.................... 27 § 55-7.1 - Intent.................... 27 § 55-7.2 - Permitted and Special Exception Uses........................ 27 § 55-7.3 - Dimensional Regulations... 28 ARTICLE 8 WF WATERFRONT DISTRICT................ 28 § 55-8.1 - Intent.................... 28 § 55-8.2 - Permitted and Special Exception Uses........................ 28 § 55-8.3 - Dimensional Regulations... 28 § 55-8.4 - WF District -

Parking Meter, 15-Minute Space Or Loading Zone from 7 A.M

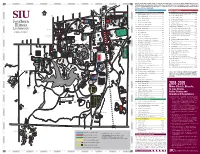

A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R Students, faculty and staff must display a current decal to park a vehicle or bicycle on campus, including metered spaces, 15-minute spaces and loading zones. Vehicles with a green overnight East or green overnight West or yellow commuter decal STUDIO 102 ARTS BUILDING may not use any parking meter, 15-minute space or loading zone from 7 a.m. to 4 p.m. Monday through Friday. Do not back 1 BLOCK NORTH 1 1 into spaces. All meters must be paid. Blue Decal Parking Lots Red Decal Parking Lots HESTER STREET no. description grid location no. description grid location WASHINGTON SQUARE COMPLEX 3 East Grand Avenue/Washington Street ..............O-5 RAINBOW'S END ALLEY 1 West of Lawson Hall ............................................... J-5 N RESTRICTED MARION STREET 2 THOMPSON STREET 94 70 2 6A North of Morris Library .......................................... L-5 RESERVED RESTRICTED 2 East of Anthony Hall ...............................................O-6 STOKER STREET POPLAR STREET 7 North of Pulliam Hall ............................................... L-3 86 RESERVED RESERVED RAWLINGS STREET RAWLINGS 6 North of Morris Library .......................................... L-5 LINCOLN DRIVE RAILROAD CENTRAL ILLINOIS WASHINGTON SQ. PATIENT RESTRICTED STUDENT PARKING 11 North of Travel Service ......................................... N-8 0421 FOREST AVENUE FOREST AVENUE NUE RECREATION 113 7 North of Pulliam Hall ............................................... L-3 MILL STREET SOUTH NORMAL AVENUE JAMES STREET CENTER STATE ST 14 West of University Park Commons .......................P-6 7 AFROTC VE NORTHWEST A 3 ANNEX C LO 3 9 Northwest of Pulliam Hall ......................................K-3 SOUTH OAKLAND AVENUE 0417 C KTO W ER D RIVE 5 21 RESERVED 18 South of Arena ......................................................M-13 LINCOLN DRIVE 9 19 HEALTH 10 Southeast of Anthony Hall ................................... -

Coweta County Zoning and Development Ordinance

Coweta County Zoning and Development Ordinance APPENDIX A ZONING Article 1. Preamble and Enactment Clause. Article 2. Provision of Official Zoning Map and Establishment of Districts. Sec. 20. Official Zoning Map. Sec. 21. Amendments to Map. Sec. 22. Replacement of Official Zoning Map. Sec. 23. Rules for Interpretation of District Boundaries. Sec. 24. Districts Listed. Article 2.1. Provision of Official Coweta County Functional Classification and Thoroughfare Map. Section 20.1. Official Functional Classification and Thoroughfare Map. Article 3. Definitions of Terms. Sec. 30. Interpretation of Certain Terms and Words. Sec. 31. Listing of Definitions. Sec. 31.1. [Reserved]. Sec. 31.2. Definitions of Verbiage Within a Flood Hazard District. Article 4. Application of Regulations. Sec. 40. Use. Sec. 41. Height and Density. Sec. 42. Yard Use Limitations. Sec. 43. One Principal Building per Lot. Sec. 44. Reduction in Lot Area. Sec. 45. Yard Requirements of Accessory Buildings. Sec. 46. Attachment of Accessory Buildings to Principal Buildings. Sec. 47. Distance between Buildings. Sec. 48. Frontage on Corner Lots and Double-Frontage Lots. Sec. 49. Minimum Street Frontage. 2 Article 5. Nonconforming Uses. Sec. 50. Nonconforming Uses Permitted. Sec. 51. Unsafe buildings. Sec. 52. Construction Approved Prior to Adoption of Ordinance. Sec. 53. Restoration. Sec. 54. Abandonment. Sec. 55. Change to Another Nonconforming Use Not Allowed. Sec. 56. Changes. Sec. 57. Enlargement. Article 6. Exceptions and Modifications. Sec. 60. Lot of Record. Sec. 61. Reduction in Building Setback Line. Sec. 62. Height Limitation Exceptions. Sec. 63. Yards in Group Developments. Sec. 64. Walls and Fences. Sec. 65. Temporary Buildings. Sec. 66. -

Section 2: Definition of Terms

SECTION 2: DEFINITION OF TERMS Subdivision 1: Purpose For the purpose of this ordinance, the following words and terms shall be interpreted as herein defined. Words in the present tense include the future; words in the singular include the plural; words in the plural include the singular; the word “shall” is mandatory; and the word “may” is permissive. A. Abut, Abuts, or Abutting These terms refer to areas with boundaries, which physically touch one another at least at a single point, provided however that when used in the context of annexation; said terms shall also be construed to include areas having boundaries, which would touch but for an intervening roadway, railroad, waterway or parcel of publically owned land. Access A means of vehicular approach or entry to or exit from property. Accessory Structure A subordinate attached or detached building located on the same lot as the principal building, of which the use is incidental and accessory to the use of the principal building. FIGURE 1: Principal and Accessory Structures Property line Accessory Structure, Attached An accessory building or structure that immediately abuts the principal building; is connected by a common wall, an enclosed passageway, breezeway, or other similar roof structure. Accessory Structure, Detached An accessory building or structure that does not immediately abuts the principal building; is not connected by a common wall, an enclosed passageway, breezeway, or other similar roof structure. Such structure is entirely surrounded by open space on the same lot as the principal building. Accessory Use A use that is (1) incidental and subordinate in area, extent, and purpose to the principal use; (2) contributes to the comfort, convenience, or necessity of the principal use; (3) is located on the same lot or within the same building; and within the same zoning district as the principal use by the same party as the principal use, and (4) will not alter the character of the area or be detrimental thereto. -

Glossary of Ship and Boat Building Terms

SHIP AND BOAT BUILDING TERMS Glossary: A collection of lists and explanations of abstruse, obsolete, dialectical or technical terms. O.E.D. Reference Document: Modern Shipbuilding Terms F. Forrest Pease, J. B. Lippincott Company This glossary gives definitions of many (but by no means all) of the ship/boat construction terms the marine surveyor will find. They relate to the hull only and are mainly those that the author learned when he was an apprentice shipwright. They include some very ancient ones and a few that are now obsolete but were still in use, again, when the author was a shipwright. The glossary is not confined to words used on small wooden or metal pleasure boats as it includes words relating to the construction and survey of vessels built of other materials and also many words relating to the commercial vessels that come within the small craft definition such as barges, coasters, small bulk carriers, tugs and trawlers, dredgers etc. It is useful to include such of these definitions as are appropriate as an appendix to any report prepared by the marine surveyor for expert witness or other legal purposes. The reference document above gives a number of terms not found in this glossary as it is aligned to big shipbuilding rather than small craft. It is, nevertheless, a useful addition to the marine surveyor’s library. Where American terms are known by the author to be different from the British both are given. Words specific to frp boats, canal boats and ferrocement are given in other glossaries in the relevant chapters above. -

Ordinance 2012-12 Page 3

Ordinance 2012-12 page 3 ORDINANCE 2012-12 SCHEDULE A CHAPTER 240, LAND SUBDIVIOSN & SITE PLAN Town of Newton CHAPTER 240 LAND SUBDIVISION & SITE PLAN CHAPTER 320 FORM-BASED CODE CHAPTER 139 HISTORIC PRESERVATION Newton Land Development Ordinances Effective May 2, 2012 CHAPTER 240 – LAND SUBDIVISION AND SITE PLAN 240-1. Title and Purpose, Approving Agency 240-2. Definitions 240-3. Subdivision and Site Plan Procedures 240-4. Plat and Plan Details 240-5. Improvements 240-6. Street and Stormwater Design Standards 240-7. Subdivision and Site Plan General Design Standards 240-8. Off-Street Parking/Loading 240-9. Signs 240-10. Wellhead Protection 240-11. Steep Slopes 240-12. Riparian Zones 240-13. Reserved 240-14. Reserved 240-15. Reserved 240-16. Guarantees and Substantial Completion 240-17. Validity 240-18. Administration and Enforcement Schedule A: Lighting Schedule B: Major Pollutant Sources Schedule C: Types of Facilities or Uses That Are Deemed Major Pollutant Sources Schedule D: Wellhead Protection Area Map Schedule C: Riparian Zones Map Schedule D: Planning Board Application Checklist 240:1 Section 240-1. Title and Purpose, Approving Agency A. TITLE & PURPOSE This Chapter shall be known and may be cited as the land subdivision and site plan ordinance of the Town of Newton. The purpose of the Chapter shall be to provide rules, regulations and standards to guide land subdivision and site plan review in the Town of Newton in order to promote health, safety, convenience and general welfare of the municipality. It shall be administered to ensure the orderly growth and development, the conservation, protection and proper use of land and adequate provisions for circulation, utilities and services. -

Mercury's Turnpike Cruiser

I T G STORY AND PHOTOGRAPHY BY MATT AVERY This stunning example of a 1957 Mercury Turnpike Cruiser is owned by Bill Konieczny of Carol Stream, Ill. coupled with longer, so er front coil springs, all of Mercury’s Turnpike Cruiser which soaked up bumps and road noises. In spite of the glamor and glitz, the Turnpike Cruiser failed to overwhelm buyers. Quality control HE 1957 MERCURY TURNPIKE CRUISER overhangs and slim B-pillars, was all new and sup- issues couldn’t be overcome, despite the buzz and was advertised as being ‘straight out of to- posed to give the illusion of it oating ‘atop a picture- excitement of a convertible model pacing the 1957 morrow’ and it really was. Besides over-the- window expanse of glass’. Indianapolis 500 race. Top Mercury execs expected topT styling and pizzazz, it featured the most whiz- It wasn’t just fabulous looks; designers wanted more and a er the 1958 model year, the opulent bang gadgetry that had ever been put in a Mercury, or an ‘entirely new concept of motoring pleasure’ to be knock-out was dropped. even parent company, Ford, before. found in the Turnpike Cruiser, incorporating many e long, low Turnpike Cruiser got its gorgeous, forward-thinking elements. Great views came from show-car looks from a 1956 concept car, and be- the ‘Skylight Dual-Curve’ windshield that not only Collectible Insights ing the golden age of space aspirations, a projectile wrapped around the side of the front passengers, A total of 7,291 two-door hardtops were made and today, Hagerty Insurance values one theme was prevalent. -

Vehicle Data Codes As of March 31, 2021 Vehicle Data Codes Table of Contents

Vehicle Data Codes As of March 31, 2021 Vehicle Data Codes Table of Contents 1 Introduction to License Plate Type Field Codes 1.1 License Plate Type Field Usage 1.2 License Plate Type (LIT) Field Codes 2 Vehicle Make and Brand Name Field Codes 2.1 Vehicle Make (VMA) and Brand Name (BRA) Field Codes by Manufacturer 2.2 Vehicle Make/Brand (VMA) and Model (VMO) for Automobiles, Light-Duty Vans, Light-Duty Trucks, and Parts 2.3 Vehicle Make/Brand Name (VMA) Field Codes for Construction Equipment and Construction Equipment Parts 2.4 Vehicle Make/Brand Name (VMA) Field Codes for Farm and Garden Equipment and Farm Equipment Parts 2.5 Vehicle Make/Brand Name (VMA) Field Codes for Motorcycles and Motorcycle Parts 2.6 Vehicle Make/Brand Name (VMA) Field Codes for Snowmobiles and Snowmobile Parts 2.7 Vehicle Make/Brand Name (VMA) Field Codes for Trailer Make Index Field Codes 2.8 Vehicle Make/Brand Name (VMA) Field Codes for Trucks and Truck Parts 3 Vehicle Model Field Codes 3.1 Vehicle Model (VMO) Field Codes 3.2 Aircraft Make/Brand Name (VMO) Field Codes 4 Vehicle Style (VST) Field Codes 5 Vehicle Color (VCO) Field Codes 6 Vehicle Category (CAT) Field Codes 7 Vehicle Engine Power or Displacement (EPD) Field Codes 8 Vehicle Ownership (VOW) Field Codes 1.1 - License Plate Type Field Usage A regular plate is a standard 6" x 12" plate issued for use on a passenger automobile and containing no embossed wording, abbreviations, and/or symbols to indicate that the license plate is a special issue. -

Use Regulations

SECTION 13: USE REGULATIONS Article 1 Residential Use Regulations 13-2 Subdivision 1 Adult Day Center Subdivision 2 Bed and Breakfast Establishments Subdivision 3 Group Housing Projects Subdivision 4 Home Occupations Subdivision 5 Manufactured Home Development Subdivision 6 Residential Conversions Article 2 Non-Residential Use Regulations 13-14 Subdivision 1 Adult Day Center Subdivision 2 Automobile Car Wash Establishments Subdivision 3 Day Care Center Subdivision 4 Drive-Thru Facilities Subdivision 5 Extended Home Occupations Subdivision 6 Farmer’s Markets Subdivision 7 Gas Stations and / or Convenience Stores Subdivision 8 Household Maintenance and Small Engine Repair Facilities Subdivision 9 Meat Processing Facilities Subdivision 10 Motor Vehicle Body Shops and Repair Facilities Subdivision 11 Motor Vehicle Sales and Rental / Leasing Facilities Subdivision 12 Open Sales Lots Subdivision 13 Outdoor Patios and Decks Subdivision 14 Outdoor Seating Subdivision 15 Outdoor Storage Subdivision 16 Recreational Vehicle Repair Facility Subdivision 17 Smoking Shelters Subdivision 18 Telecommunication and Antenna Towers Subdivision 29 Temporary Outdoor Sales / Transient Merchants Subdivision 20 Temporary Real Estate Offices Subdivision 21 Wind Energy Conversion Systems Article 3 Use Regulations in All Zoning Districts 13-31 Subdivision 1 Land Alterations Article 4 Accessory Buildings, Structures and Uses 13-33 Subdivision 1 Residential Districts Subdivision 2 Business and Industrial Districts City of Isanti Zoning Ordinance Page 13-1 ARTICLE ONE: RESIDENTIAL USE REGULATIONS Subdivision 1: Adult Day Center (Ord. No. 594) A. Purpose. The purpose of this section is to ensure the safety and wellbeing of the facilities clients. B. Safety and Security Measures. A plan shall be submitted as part of the permit review. -

January 19, 2021 Avondale Amendments to the 2018

January 19, 2021 Avondale Amendments to the 2018 International Fire Code Page 1 of 103 The International Fire Code, 2018 Edition, as published by the International Code Council, is amended in the following respects: Section 101 is deleted in its entirety and replaced with the following: 101.1 Title. These regulations shall be known as the Fire Code of the City of Avondale, hereinafter referred to as “this code”. 101.2 Scope. This code establishes regulations affecting or relating to structures, processes, premises and safeguards regarding all of the following: 1. The hazard of fire and explosion arising from the storage, handling or use of structures, materials or devices. 2. Conditions hazardous to life, property, or public welfare in the occupancy of structures or premises. 3. Fire hazards in the structure or on the premises from occupancy or operation. 4. Matters related to the construction, extension, repair, alteration or removal of fire suppression or alarm systems. 5. Conditions affecting the safety of fire fighters and emergency responders during emergency operations. 101.2.1 Appendices. The following appendices are adopted by the City of Avondale: Appendix E, F, G, H, I, L, and N. 101.3 Intent. The purpose of this code is to establish the minimum requirements consistent with nationally recognized good practice for providing a reasonable level of life safety and property protection from the hazards of fire, explosion or dangerous conditions in new and existing buildings, structures and premises, and to provide a reasonable level of safety to fire fighters and emergency responders during emergency operations. 101.4 Severability. -

Comprehensive Zoning Ordinance Augusta, Georgia

COMPREHENSIVE ZONING ORDINANCE OF AUGUSTA, GEORGIA Editorial revision of the Ordinance adopted March 25, 1963, incorporating changes made necessary by the Home Rule Provision of the Constitution of the State of Georgia of 1983, and the consolidation of the City of Augusta and Richmond County, and other amendments between November 15, 1983 and January 3, 2006 and September 7, 2011 Amended April 2020 Amended November 2019 Amended August 2018 Amended March 2018 Amended February 2018 Amended December 2017 Amended August 2017 Amended June 2017 March 2017 Amended January 2017 Amended July 2016 Amended March 2016 Amended October 2015 Amended August 2015 Amended July 2015 Amended June 2015 Amended January 2015 Amended November 2014 Amended May 2014 Amended September 2013 1- 1 AN ORDINANCE BY THE AUGUSTA COMMISSION TO ADOPT A COMPREHENSIVE ZONING PLAN, MAPS AND LAND USE REGULATIONS; TO REPEAL CONFLICTING ORDINANCES AND FOR OTHER PURPOSES: WHEREAS, the Augusta Commission, was authorized by the Home Rule Provision of the Constitution of the State of Georgia of 1983 to: Establish planning commissions; provide for the preparation and amendment of overall plans for the orderly growth and development of municipalities and counties; provide for the regulation of structures on mapped streets, public building sites, and public open spaces; repeal conflicting laws; and for other purposes; and WHEREAS, the Augusta, Georgia Planning Commission, created and organized under the terms of the aforementioned Home Rule Provision, has made a study and analysis of the areas of Augusta, Georgia and the said study and analysis now are complete and a Comprehensive Zoning Plan consisting of the maps and regulations described herein for the purposes described in the title of this Ordinance are now ready for adoption; and WHEREAS, the Commission has held a public hearing on the proposed Comprehensive Zoning Plan after giving more than fifteen (15) days notice of the time and place of such hearing by publication in the Augusta Chronicle as provided by the official code of Georgia. -

Center Opening Doors Return to the Continental Lincoln's New Pride

Volume 19 Issue 1S January 1, 2019 Center opening doors return to the Continental Lincoln’s new Pride and Joy “Notice the doors,” the vintage advertisement for the Lincoln Continental began. “And notice how they open. From the center, to make everyone’s entrances graceful.” With that, an enduring automotive design legend was born – the coach doors – or center-opening doors; which conveyed elegance and a touch of Hollywood glamour. Today, six decades later, Lincoln is bringing back a modern version of these iconic center-opening doors with the introduction of the Lincoln Continental 80th Anniversary Coach Door Edition. A limited run of just 80 units will be produced. The Continental Coach Door Edition arrives as Lincoln is riding a new wave of prod- Welcome to the uct momentum. Following the reveal of the all-new Lincoln Aviator at the Los Angeles Northstar News, the Auto Show, this 80th Anniversary Continental celebrates the heritage of one of Amer- monthly publication of ica’s most beloved luxury sedans. the Northstar Region “This Lincoln Continental echoes a design that captured the hearts of car enthusiasts around the world,” says Joy Falotico, President, The Lincoln Motor Company. “It’s of the Lincoln and something bespoke only Lincoln can offer in a thoroughly modern way.” Continental Owners Glamour and allure. Lincoln Continental began as a custom luxury vehicle hand- Club. We value your crafted by chief stylist Eugene T. Gregorie for Edsel Ford in 1939. Years later, the 1961 opinions and appreciate Continental introduced the unique center-opening doors and a chrome-accented upper your input concerning shoulder line that established a signature look for Lincoln.