Nelson T. Sambureni

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Directory of Organisations and Resources for People with Disabilities in South Africa

DISABILITY ALL SORTS A DIRECTORY OF ORGANISATIONS AND RESOURCES FOR PEOPLE WITH DISABILITIES IN SOUTH AFRICA University of South Africa CONTENTS FOREWORD ADVOCACY — ALL DISABILITIES ADVOCACY — DISABILITY-SPECIFIC ACCOMMODATION (SUGGESTIONS FOR WORK AND EDUCATION) AIRLINES THAT ACCOMMODATE WHEELCHAIRS ARTS ASSISTANCE AND THERAPY DOGS ASSISTIVE DEVICES FOR HIRE ASSISTIVE DEVICES FOR PURCHASE ASSISTIVE DEVICES — MAIL ORDER ASSISTIVE DEVICES — REPAIRS ASSISTIVE DEVICES — RESOURCE AND INFORMATION CENTRE BACK SUPPORT BOOKS, DISABILITY GUIDES AND INFORMATION RESOURCES BRAILLE AND AUDIO PRODUCTION BREATHING SUPPORT BUILDING OF RAMPS BURSARIES CAREGIVERS AND NURSES CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — EASTERN CAPE CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — FREE STATE CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — GAUTENG CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — KWAZULU-NATAL CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — LIMPOPO CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — MPUMALANGA CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — NORTHERN CAPE CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — NORTH WEST CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — WESTERN CAPE CHARITY/GIFT SHOPS COMMUNITY SERVICE ORGANISATIONS COMPENSATION FOR WORKPLACE INJURIES COMPLEMENTARY THERAPIES CONVERSION OF VEHICLES COUNSELLING CRÈCHES DAY CARE CENTRES — EASTERN CAPE DAY CARE CENTRES — FREE STATE 1 DAY CARE CENTRES — GAUTENG DAY CARE CENTRES — KWAZULU-NATAL DAY CARE CENTRES — LIMPOPO DAY CARE CENTRES — MPUMALANGA DAY CARE CENTRES — WESTERN CAPE DISABILITY EQUITY CONSULTANTS DISABILITY MAGAZINES AND NEWSLETTERS DISABILITY MANAGEMENT DISABILITY SENSITISATION PROJECTS DISABILITY STUDIES DRIVING SCHOOLS E-LEARNING END-OF-LIFE DETERMINATION ENTREPRENEURIAL -

Know Your Vaccination Sites for Phase 2:Week 26 July -01 August 2021 Sub-Distrct Facility/Site Ward Address Operating Days Operating Hours

UTHUKELA HEALTH DISTRICT VACCINATION SITES FOR THE WEEK 26-31 JULY 2021 SUB- FACILITY/SITE WARD ADDRESS OPERATING DAYS OPERATING HOURS DISTRCT Inkosi ThusongKNOWHall YOUR14 Next to oldVACCINATION Mbabazane 26 - 30 July 2021 08:00 – 16:00 Langalibalele Ntabamhlope Municipal offices Inkosi Weenen Comm Hall 20 Next to municipal offices 26- 30 July 2021 08:00 – 16:00 Langalibalele SITES Inkosi Wembezi Hall 9 VQ Section 26- 30 July 2021 08:00 – 16:00 Langalibalele Inkosi Forderville Hall 10 Canna Avenue 26-30 July 2021 08:00 – 16:00 Langalibalele Fordeville Inkosi Mahlutshini Hall 12 Next to Mahlutshini Tribal 26- 30 July 2021 08:00 – 16:00 Langalibalele Court Inkosi Phasiwe Hall 6 Next to Phasiwe Primary 26- 30 July 2021 08:00 – 16:00 Langalibalele School Inkosi Estcourt hospital 23 No. 1 Old main Road, 26-30 July 2021 08:00 – 16:00 Langalibalele southwing nurses home Estcourt UTHUKELA HEALTH DISTRICT VACCINATION SITES FOR THE WEEK 26-31 JULY 2021 SUB- FACILITY/SITE WARD ADDRESS OPERATING DAYS OPERATING HOURS DISTRCT Inkosilangali MoyeniKNOWHall 2 YOURLoskop Area -VACCINATIONnext to Mjwayeli P 31 Jul-01 Aug 2021 08:00 – 16:00 balele School Inkosilangali Geza Hall 5 Next to Jafter Store – Loskop 31 Jul-01 Aug 2021 08:00 – 16:00 balele Area SITES Inkosilangali Mpophomeni Hall 1 Loskop Area at Ngodini 31 Jul-01 Aug 2021 08:00 – 16:00 balele Inkosilangali Mdwebu Methodist 14 Ntabamhlophe Area- Next to 31 Jul- 01 Aug 08:00 – 16:00 balele Church Mdwebu Hall 2021 Inkosilangali Thwathwa Hall 13 Kwandaba Area at 31 Jul-01 Aug 2021 08:00 – 16:00 balele -

Ward Councillors Pr Councillors Executive Committee

EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE KNOW YOUR CLLR WEZIWE THUSI CLLR SIBONGISENI MKHIZE CLLR NTOKOZO SIBIYA CLLR SIPHO KAUNDA CLLR NOMPUMELELO SITHOLE Speaker, Ex Officio Chief Whip, Ex Officio Chairperson of the Community Chairperson of the Economic Chairperson of the Governance & COUNCILLORS Services Committee Development & Planning Committee Human Resources Committee 2016-2021 MXOLISI KAUNDA BELINDA SCOTT CLLR THANDUXOLO SABELO CLLR THABANI MTHETHWA CLLR YOGISWARIE CLLR NICOLE GRAHAM CLLR MDUDUZI NKOSI Mayor & Chairperson of the Deputy Mayor and Chairperson of the Chairperson of the Human Member of Executive Committee GOVENDER Member of Executive Committee Member of Executive Committee Executive Committee Finance, Security & Emergency Committee Settlements and Infrastructure Member of Executive Committee Committee WARD COUNCILLORS PR COUNCILLORS GUMEDE THEMBELANI RICHMAN MDLALOSE SEBASTIAN MLUNGISI NAIDOO JANE PILLAY KANNAGAMBA RANI MKHIZE BONGUMUSA ANTHONY NALA XOLANI KHUBONI JOSEPH SIMON MBELE ABEGAIL MAKHOSI MJADU MBANGENI BHEKISISA 078 721 6547 079 424 6376 078 154 9193 083 976 3089 078 121 5642 WARD 01 ANC 060 452 5144 WARD 23 DA 084 486 2369 WARD 45 ANC 062 165 9574 WARD 67 ANC 082 868 5871 WARD 89 IFP PR-TA PR-DA PR-IFP PR-DA Areas: Ebhobhonono, Nonoti, Msunduzi, Siweni, Ntukuso, Cato Ridge, Denge, Areas: Reservoir Hills, Palmiet, Westville SP, Areas: Lindelani C, Ezikhalini, Ntuzuma F, Ntuzuma B, Areas: Golokodo SP, Emakhazini, Izwelisha, KwaHlongwa, Emansomini Areas: Umlazi T, Malukazi SP, PR-EFF Uthweba, Ximba ALLY MOHAMMED AHMED GUMEDE ZANDILE RUTH THELMA MFUSI THULILE PATRICIA NAIR MARLAINE PILLAY PATRICK MKHIZE MAXWELL MVIKELWA MNGADI SIFISO BRAVEMAN NCAYIYANA PRUDENCE LINDIWE SNYMAN AUBREY DESMOND BRIJMOHAN SUNIL 083 7860 337 083 689 9394 060 908 7033 072 692 8963 / 083 797 9824 076 143 2814 WARD 02 ANC 073 008 6374 WARD 24 ANC 083 726 5090 WARD 46 ANC 082 7007 081 WARD 68 DA 078 130 5450 WARD 90 ANC PR-AL JAMA-AH 084 685 2762 Areas: Mgezanyoni, Imbozamo, Mgangeni, Mabedlane, St. -

Location in Africa the Durban Metropolitan Area

i Location in Africa The Durban Metropolitan area Mayor’s message Durban Tourism am delighted to welcome you to Durban, a vibrant city where the Tel: +27 31 322 4164 • Fax: +27 31 304 6196 blend of local cultures – African, Asian and European – is reected in Email: [email protected] www.durbanexperience.co.za I a montage of architectural styles, and a melting pot of traditions and colourful cuisine. Durban is conveniently situated and highly accessible Compiled on behalf of Durban Tourism by: to the world. Artworks Communications, Durban. Durban and South Africa are fast on their way to becoming leading Photography: John Ivins, Anton Kieck, Peter Bendheim, Roy Reed, global destinations in competition with the older, more established markets. Durban is a lifestyle Samora Chapman, Chris Chapman, Strategic Projects Unit, Phezulu Safari Park. destination that meets the requirements of modern consumers, be they international or local tourists, business travellers, conference attendees or holidaymakers. Durban is not only famous for its great While considerable effort has been made to ensure that the information in this weather and warm beaches, it is also a destination of choice for outdoor and adventure lovers, eco- publication was correct at the time of going to print, Durban Tourism will not accept any liability arising from the reliance by any person on the information tourists, nature lovers, and people who want a glimpse into the unique cultural mix of the city. contained herein. You are advised to verify all information with the service I welcome you and hope that you will have a wonderful stay in our city. -

KNOW YOUR VACCINATION SITES for PHASE 2:WEEK 02 August -08 August 2021

NAME OF YOUR DISTRICT: ILEMBE OUTREACH VACCINATION SITES FOR PHASE 2:WEEK 02- 08 AUGUST 2021 SUB-DISTRCT FACILITY/SITEKNOW YOURWARD ADDRESS VACCINATIONOPERATING DAYS OPERATING HOURS KWADUKUZA DRIEFONTEIN HALL 21 SITESDRIEFONTEIN 02/08/2021 09:00- 15:00 DORINKOP HALL 25 DORINKOP 03/08/2021 09:00-15:00 MADUNDUBE HALL 27 MADUNDUBE 04/08/2021 08:00- 16:00 SHAKAVILLE HALL 18 SHAKAVILLE 05/08/2021 08:00- 16:00 TOWNSEND PARK HALL 6 BALLITO 06-08/2021 08:00- 16:00 NAME OF YOUR DISTRICT: ILEMBE OUTREACH VACCINATION SITES FOR PHASE 2:WEEK 02- 08 AUGUST 2021 SUB-DISTRCT FACILITY/SITEKNOW YOURWARD ADDRESS VACCINATIONOPERATING DAYS OPERATING HOURS MAPHUMULO POYINANDI HALL 2 NTUNJAMBILI 02- 06/08/2021 09:00- 15:00 THETHANDABA HALL 2 SITES 02- 06/08/2021 NTUNJAMBILI 09:00- 15:00 LUTHERAN CHURCH 1 NTUNJAMBILI 02- 06/08/2021 09:00- 15:00 PHAKADE HALL 9 MATENDENI, OTIMATI 02- 06/08/2021 09:00- 16:00 NAME OF YOUR DISTRICT: ILEMBE OUTREACH VACCINATION SITES FOR PHASE 2:WEEK 02- 08 AUGUST 2021 SUB-DISTRCT FACILITY/SITE WARD ADDRESS OPERATING DAYS OPERATING HOURS NDWEDWE MAQOKOMELAKNOW YOUR19 MAQOKOMELA VACCINATION02/08/2021 09H00 -15H30 MWOLOKOHLO CLINIC 11 SITESMWOLOKOHLO CLINIC 02/08/2021 07H-16H00 TUSONG CENTRE 10 SONKOMBO AREA 03/08/2021 09H00-15H30 WATERFALL & MAGWAZA 3 UPPER TONGAAT 03/08/2021 09H00-15H30 BHANOYI COMMUNITY HALL 14 NTAPHUKA AREA 04/08/2021 09H00-15H30 THAFAMASI 18 THAFAMSI CLINI 05/08/2021 09H00-15H30 MAYENDISA 12 MTHEBENI AREA 05/08/2021 09H00-15H30 MESATSHWA 14 NTAPHUKA AREA 06/08/2021 09H00-15H30 DISTRICT : ILEMBE OUTREACH VACCINATION -

DURBAN NORTH 957 Hillcrest Kwadabeka Earlsfield Kenville ^ 921 Everton S!Cteelcastle !C PINETOWN Kwadabeka S Kwadabeka B Riverhorse a !

!C !C^ !.ñ!C !C $ ^!C ^ ^ !C !C !C!C !C !C !C ^ ^ !C !C ^ !C !C !C !C !C ^ !C ñ !C !C !C !C !C ^ !C !C ^ !C !C $ !C ^ !C !C !C !C !C !C ^ !C ^ ñ !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !. !C ^ ñ ^ !C !C !C !C !C !C $ !C !C ^ !C ^ !C !C !C ñ !C !C !C ^ !C !.ñ ñ!C !C !C !C ^ !C ^ !C ^ !C ^ !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C ^ ñ !C !C !C !C !C !C ^ ñ !C !C ñ !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C ñ !C !C ^ ^ !C !C !. !C !C ñ ^ !C ^ !C ñ!C !C ^ ^ !C !C $ ^!C $ ^ !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !. !C !C !C ñ!.^ $ !C !C !C ^ !C !C !C !C $ !C ^ !C !C $ !C !C ñ $ !. !C !C !C !C !C !C !. ^ ñ!C ^ ^ !C $!. ^ !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !. !C !C !C !C !C ^ !C !. !C !C ñ!C !C !C !C ^ ñ !C !C ñ !C !C !. ^ !C !C !C !C !C !C !C ^ !C ñ ^ $ ^ !C ñ !C !C !. ñ ^ !C !. !C !C ^ ñ !. ^ ñ!C !C $^ ^ ^ !C ^ ñ ^ !C ^ !C !C !C !C !C !C ^ !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !. !C ^ !C $ !C !. ñ !C !C ^ !C ñ!. ^ !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C $!C !. !C ^ !. !. !C !C !. ^ !C !C !C ^ ^ !C !C ñ !C !. -

Following Is a Load Shedding Schedule That People Are Advised to Keep

Following is a load shedding schedule that people are advised to keep. STAND-BY LOAD SHEDDING SCHEDULE Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday Sunday Block A 04:00-06:30 08:00-10:30 04:00-06:30 08:00-10:30 04:00-06:30 08:00-10:30 08:00-10:30 Block B 06:00-08:30 14:00-16:30 06:00-08:30 14:00-16:30 06:00-08:30 14:00-16:30 14:00-16:30 Block C 08:00-10:30 16:00-18:30 08:00-10:30 16:00-18:30 08:00-10:30 16:00-18:30 16:00-18:30 Block D 10:00-12:30 12:00-14:30 10:00-12:30 12:00-14:30 10:00-12:30 12:00-14:30 12:00-14:30 Block E 12:00-14:30 10:00-12:30 12:00-14:30 10:00-12:30 12:00-14:30 10:00-12:30 10:00-12:30 Block F 14:00-16:30 18:00-20:30 14:00-16:30 18:00-20:30 14:00-16:30 18:00-20:30 18:00-20:30 Block G 16:00-18:30 20:00-22:30 16:00-18:30 20:00-22:30 16:00-18:30 20:00-22:30 20:00-22:30 Block H 18:00-20:30 04:00-06:30 18:00-20:30 04:00-06:30 18:00-20:30 04:00-06:30 04:00-06:30 Block J 20:00-22:30 06:00-08:30 20:00-22:30 06:00-08:30 20:00-22:30 06:00-08:30 06:00-08:30 Area Block Albert Park Block D Amanzimtoti Central Block B Amanzimtoti North Block B Amanzimtoti South Block B Asherville Block H Ashley Block J Assagai Block F Athlone Block G Atholl Heights Block J Avoca Block G Avoca Hills Block C Bakerville Gardens Block G Bayview Block B Bellair Block A Bellgate Block F Belvedere Block F Berea Block F Berea West Block F Berkshire Downs Block E Besters Camp Block F Beverly Hills Block C Blair Atholl Block J Blue Lagoon Block D Bluff Block E Bonela Block E Booth Road Industrial Block E Bothas Hill Block F Briardene Block G Briardene -

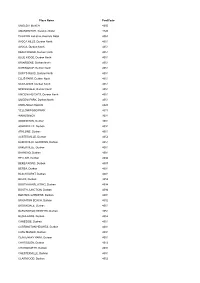

Place Name Postcode UMDLOTI BEACH 4350 AMANZIMTOTI

Place Name PostCode UMDLOTI BEACH 4350 AMANZIMTOTI, Kwazulu Natal 4126 PHOENIX Industria, Kwazulu Natal 4068 AVOCA HILLS, Durban North 4051 AVOCA, Durban North 4051 BEACHWOOD, Durban North 4051 BLUE RIDGE, Durban North 4051 BRIARDENE, Durban North 4051 DORINGKOP, Durban North 4051 DUFF'S ROAD, Durban North 4051 ELLIS PARK, Durban North 4051 NEWLANDS, Durban North 4051 SPRINGVALE, Durban North 4051 UMGENI HEIGHTS, Durban North 4051 UMGENI PARK, Durban North 4051 UMHLANGA ROCKS 4320 YELLOWWOOD PARK 4011 WANDSBECK 3631 ADDINGTON, Durban 4001 ASHERVILLE, Durban 4091 ATHLONE, Durban 4051 AUSTERVILLE, Durban 4052 BAKERVILLE GARDENS, Durban 4051 BAKERVILLE, Durban 4051 BAYHEAD, Durban 4001 BELLAIR, Durban 4094 BEREA ROAD, Durban 4007 BEREA, Durban 4001 BLACKHURST, Durban 4001 BLUFF, Durban 4052 BOOTH AANSLUITING, Durban 4094 BOOTH JUNCTION, Durban 4094 BOTANIC GARDENS, Durban 4001 BRIGHTON BEACH, Durban 4052 BROOKDALE, Durban 4051 BURLINGTON HEIGHTS, Durban 4051 BUSHLANDS, Durban 4052 CANESIDE, Durban 4051 CARRINGTON HEIGHTS, Durban 4001 CATO MANOR, Durban 4091 CENTENARY PARK, Durban 4051 CHATSGLEN, Durban 4012 CHATSWORTH, Durban 4092 CHESTERVILLE, Durban 4001 CLAIRWOOD, Durban 4052 CLARE Est/Lgd, Durban 4091 CLAYFIELD, Durban 4051 CONGELLA, Durban 4001 DALBRIDGE, Durban 4001 DORMERTON, Durban 4091 DURBAN NORTH, Durban 4051 DURBAN-NOORD, Durban 4051 Durban International Airport, Durban 4029 EARLSFIELD, Durban 4051 EAST END, Durban 4018 EASTBURY, Durban 4051 EFFINGHAM HEIGHTS, Durban 4051 FALLODEN PARK, Durban 4094 FLORIDA ROAD, Durban 4019 FOREST -

Race, Politics and Religion: the First Catholic Mission in Zululand (1895-1907)

Race, politics and religion: the first Catholic mission in Zululand (1895-1907) Philippe Denis School of Religion and Theology, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Pietermaritzburg, South Africa Abstract This paper explores the strategies deployed by the Catholic authorities in the late 19th century to gain access to Zululand, their approach to race relations and their relationship to the colonial enterprise in general. The first Catholic mission in Zululand was established in 1895 through a remarkable conjunction of events: the intervention of an ecclesiastical visi- tator, the decision made by John Dunn, the “white chief”, on his death bed to entrust the education of his children to the Catholic Church and Bishop Jolivet’s friendship with the British resident commissioner. The Catholic missionaries empathised with the Zulu culture, but remained imbued with colonial prejudices. They treated the first black Oblate and the first black priest in a discriminatory manner. Catholics were latecomers in Zululand. When they established their first mission at Emoyeni in 1895, the Lutherans and the Anglicans had been in the field for decades. Today, with two dioceses and thirty-five parishes, they are present in the entire region but numerically weak – only 81,500 church members in the diocese of Eshowe and 23,350 in the diocese of Ingwavuma, according to the Catholic Directory.1 This is much less than in the rest of KwaZulu-Natal and in many South African other provinces. The bulk of the population has joined African indigenous churches. Yet the history of the Catholic Church in Zululand is not without significance, especially in the early period. -

First Phase Heritage Impact Assessment

Mariannwood Campus FIRST PHASE HERITAGE IMPACT ASSESSMENT OF THE PROPOSED CONSTRUCTION OF MARIANNWOOD CAMPUS BUILDING AND ASSOCIATED INFRASTRUCTURE ON REMAINDER OF PORTION 79 OF THE FARM ZEEKOEGAT 937, WITHIN ETHEKWINI MUNICIPALITY. ACTIVE HERITAGE cc. FOR: MONDLI CONSULTING Frans Prins MA (Archaeology) P.O. Box 947 Howick 3290 [email protected] [email protected] www.activeheritage.webs.com 20 June 2017 Fax: 086 7636380 Active Heritage cc for Mondli Consulting i Mariannwood Campus TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 BACKGROUND INFORMATION ON THE PROJECT ........................................... 1 1.1 ARCHAEOLOGICAL HISTORY OF AREA ................................................... 2 1.2 MARRIANHILL MONASTERY ...................................................................... 4 2 BACKGROUND INFORMATION OF THE SURVEY ............................................. 8 2.1 Methodology ................................................................................................. 8 2.2 Restrictions encountered during the survey .................................................. 8 2.2.1 Visibility ..................................................................................................... 8 2.2.2 Disturbance ............................................................................................... 8 3 DESCRIPTION OF SITES AND MATERIAL OBSERVED ..................................... 9 3.1 Locational data ............................................................................................. 9 3.2 Description of the general area -

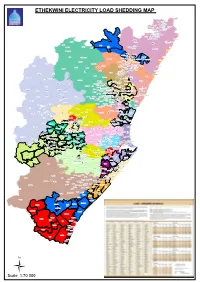

Ethekwini Electricity Load Shedding Map

ETHEKWINI ELECTRICITY LOAD SHEDDING MAP Lauriston Burbreeze Wewe Newtown Sandfield Danroz Maidstone Village Emona SP Fairbreeze Emona Railway Cottage Riverside AH Emona Hambanathi Ziweni Magwaveni Riverside Venrova Gardens Whiteheads Dores Flats Gandhi's Hill Outspan Tongaat CBD Gandhinagar Tongaat Central Trurolands Tongaat Central Belvedere Watsonia Tongova Mews Mithanagar Buffelsdale Chelmsford Heights Tongaat Beach Kwasumubi Inanda Makapane Westbrook Hazelmere Tongaat School Jojweni 16 Ogunjini New Glasgow Ngudlintaba Ngonweni Inanda NU Genazano Iqadi SP 23 New Glasgow La Mercy Airport Desainager Upper Bantwana 5 Redcliffe Canelands Redcliffe AH Redcliff Desainager Matata Umdloti Heights Nellsworth AH Upper Ukumanaza Emona AH 23 Everest Heights Buffelsdraai Riverview Park Windermere AH Mount Moreland 23 La Mercy Redcliffe Gragetown Senzokuhle Mt Vernon Oaklands Verulam Central 5 Brindhaven Riyadh Armstrong Hill AH Umgeni Dawncrest Zwelitsha Cordoba Gardens Lotusville Temple Valley Mabedlane Tea Eastate Mountview Valdin Heights Waterloo village Trenance Park Umdloti Beach Buffelsdraai Southridge Mgangeni Mgangeni Riet River Southridge Mgangeni Parkgate Southridge Circle Waterloo Zwelitsha 16 Ottawa Etafuleni Newsel Beach Trenance Park Palmview Ottawa 3 Amawoti Trenance Manor Mshazi Trenance Park Shastri Park Mabedlane Selection Beach Trenance Manor Amatikwe Hillhead Woodview Conobia Inthuthuko Langalibalele Brookdale Caneside Forest Haven Dimane Mshazi Skhambane 16 Lower Manaza 1 Blackburn Inanda Congo Lenham Stanmore Grove End Westham -

Exploring the Dynamics of Chronic Conflict in Four Selected Schools in the Durban Region

Exploring the dynamics of chronic conflict in four selected schools in the Durban region by Shobana Mandraj Student number: 991273273 A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the School of Education, University of KwaZulu-Natal, in KwaZulu-Natal Promoter: Professor Reshma Sookrajh Co-Promoter: Dr LR Maharajh January 2018 1 DECLARATION I, Shobana Mandraj declare that: 1) The research reported on in this thesis, except where otherwise indicated, is my original work. 2) This thesis has not been submitted for any degree or examination at any other university. 3) This thesis does not contain other persons’ data, pictures, graphs or other information, unless specifically acknowledged as being sourced from other persons. 4) This thesis does not contain other persons’ writing, unless specifically acknowledged as being sourced from other researchers. Where other written sources have been quoted, then: i. their words have been re-written but the general information attributed to them has been referenced; ii. where their exact words have been used, their writing has been placed inside quotation marks, and referenced. 5) This thesis does not contain text, graphics, or tables copied and pasted from the Internet, unless specifically acknowledged, and the source being detailed in the thesis and in the References sections. _________________S Mandraj ________________10 December 2018 Shobana Mandraj Date _________________R Sookrajh ________________10 December 2018 Professor Reshma Sookrajh Date Promoter _________________ ________________10 December 2018 Dr LR Maharajh Date Co-Promoter 2 DEDICATION I dedicate this thesis to: The memory of my Mum, Mrs LAXMI MANDRAJ, who passed away while I was completing this thesis, and to the memory of my late dad, Mr BADRI MANDRAJ of Pietermaritzburg, whose passion for teaching and learning instilled in me a thirst for knowledge which I hope to eternally perpetuate.