To Download the PDF File

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Entertainment & Syndication Fitch Group Hearst Health Hearst Television Magazines Newspapers Ventures Real Estate & O

hearst properties WPBF-TV, West Palm Beach, FL SPAIN Friendswood Journal (TX) WYFF-TV, Greenville/Spartanburg, SC Hardin County News (TX) entertainment Hearst España, S.L. KOCO-TV, Oklahoma City, OK Herald Review (MI) & syndication WVTM-TV, Birmingham, AL Humble Observer (TX) WGAL-TV, Lancaster/Harrisburg, PA SWITZERLAND Jasper Newsboy (TX) CABLE TELEVISION NETWORKS & SERVICES KOAT-TV, Albuquerque, NM Hearst Digital SA Kingwood Observer (TX) WXII-TV, Greensboro/High Point/ La Voz de Houston (TX) A+E Networks Winston-Salem, NC TAIWAN Lake Houston Observer (TX) (including A&E, HISTORY, Lifetime, LMN WCWG-TV, Greensboro/High Point/ Local First (NY) & FYI—50% owned by Hearst) Winston-Salem, NC Hearst Magazines Taiwan Local Values (NY) Canal Cosmopolitan Iberia, S.L. WLKY-TV, Louisville, KY Magnolia Potpourri (TX) Cosmopolitan Television WDSU-TV, New Orleans, LA UNITED KINGDOM Memorial Examiner (TX) Canada Company KCCI-TV, Des Moines, IA Handbag.com Limited Milford-Orange Bulletin (CT) (46% owned by Hearst) KETV, Omaha, NE Muleshoe Journal (TX) ESPN, Inc. Hearst UK Limited WMTW-TV, Portland/Auburn, ME The National Magazine Company Limited New Canaan Advertiser (CT) (20% owned by Hearst) WPXT-TV, Portland/Auburn, ME New Canaan News (CT) VICE Media WJCL-TV, Savannah, GA News Advocate (TX) HEARST MAGAZINES UK (A+E Networks is a 17.8% investor in VICE) WAPT-TV, Jackson, MS Northeast Herald (TX) VICELAND WPTZ-TV, Burlington, VT/Plattsburgh, NY Best Pasadena Citizen (TX) (A+E Networks is a 50.1% investor in VICELAND) WNNE-TV, Burlington, VT/Plattsburgh, -

HEARST PROPERTIES HUNGARY HEARST MAGAZINES UK Hearst Central Kft

HEARST PROPERTIES HUNGARY HEARST MAGAZINES UK Hearst Central Kft. (50% owned by Hearst) All About Soap ITALY Best Cosmopolitan NEWSPAPERS MAGAZINES Hearst Magazines Italia S.p.A. Country Living Albany Times Union (NY) H.M.C. Italia S.r.l. (49% owned by Hearst) Car and Driver ELLE Beaumont Enterprise (TX) Cosmopolitan JAPAN ELLE Decoration Connecticut Post (CT) Country Living Hearst Fujingaho Co., Ltd. Esquire Edwardsville Intelligencer (IL) Dr. Oz THE GOOD LIFE Greenwich Time (CT) KOREA Good Housekeeping ELLE Houston Chronicle (TX) Hearst JoongAng Y.H. (49.9% owned by Hearst) Harper’s BAZAAR ELLE DECOR House Beautiful Huron Daily Tribune (MI) MEXICO Laredo Morning Times (TX) Esquire Inside Soap Hearst Expansion S. de R.L. de C.V. Midland Daily News (MI) Food Network Magazine Men’s Health (50.1% owned by Hearst UK) (51% owned by Hearst) Midland Reporter-Telegram (TX) Good Housekeeping Prima Plainview Daily Herald (TX) Harper’s BAZAAR NETHERLANDS Real People San Antonio Express-News (TX) HGTV Magazine Hearst Magazines Netherlands B.V. Red San Francisco Chronicle (CA) House Beautiful Reveal The Advocate, Stamford (CT) NIGERIA Marie Claire Runner’s World (50.1% owned by Hearst UK) The News-Times, Danbury (CT) HMI Africa, LLC O, The Oprah Magazine Town & Country WEBSITES Popular Mechanics NORWAY Triathlete’s World Seattlepi.com Redbook HMI Digital, LLC (50.1% owned by Hearst UK) Road & Track POLAND Women’s Health WEEKLY NEWSPAPERS Seventeen Advertiser North (NY) Hearst-Marquard Publishing Sp.z.o.o. (50.1% owned by Hearst UK) Town & Country Advertiser South (NY) (50% owned by Hearst) VERANDA MAGAZINE DISTRIBUTION Ballston Spa/Malta Pennysaver (NY) Woman’s Day RUSSIA Condé Nast and National Magazine Canyon News (TX) OOO “Fashion Press” (50% owned by Hearst) Distributors Ltd. -

Flight of Fancy When It Comes to Bridal, Romance Is Always in Style

EYE: Partying with ▲ RETAIL: Chanel, page 4. Analyzing ▲ FASHION: Wal-Mart’s Donatella China sourcing talks New initiative, NEWS: Leslie York and page 13. Wexner is “feeling politics, good” despite the ▲ page 8. economy, page 5. WWDWomen’s Wear Daily • TheTHURSDAY Retailers’ Daily Newspaper • October 23, 2008 • $2.00 Sportswear Flight of Fancy When it comes to bridal, romance is always in style. Take, for example, this Carolina Herrera gown in silk habotai with swirls cascading from the hip and over one shoulder — a look that is as effortless as it is dreamy. For more, see pages 6 and 7. Palin’s Fashion-Gate: A Big Boost for Style, But Not for the GOP By WWD Staff At least someone is shopping: the Republicans and Sarah Palin. Given the beleaguered state of American retailing in the downward spiraling economy, stores such as Neiman Marcus, Saks Fifth Avenue, Barneys New York and Macy’s no doubt welcomed the Republican National Committee’s shopping spree on behalf of Palin with open arms. In some cases, it may even have helped goose their September same-store sales. And in this day and age, anything that boosts the profile of fashion and retailing can only be a good thing. Not that one would know it from the furor Palin’s wardrobe, hair and makeup created on Wednesday — even if the result has turned her into a politician admired for her style and See Palin’s, Page9 PHOTO BY ROBERT MITRA ROBERT PHOTO BY WWD.COM WWDTHURSDAY Sportswear FASHION Designers went in several directions for spring, ™ 6 and the best gowns had special details such as A weekly update on consumer attitudes and behavior based crystal beading, fl ower corsages or prints. -

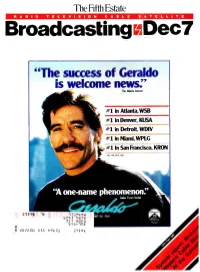

Broadcasting a Dec?

The Fifth Estate D1.0 T E L E V I S I O N C A B L E Broadcasting A Dec? "The success of Geraldo is welcome news:' The Manta Journal 761 in Atlanta, WSB #1 in Denver, !NSA #1 in Detroit, WDIV #1 in Miami, WPLG // 1 in San Francisco, KRON \y IIV.II'If 1973' ZIT9£ v 113MXdW S051 901fl ZZ T Mlp02i S rS-ltlV It N ZS /ACN NIA 44£ßl ZTI4£ /NC MI/Mlle' IN OTHER WORD MARVFLOUS!`` ..,ew World Television presents our all -time fayorite superheroes... ow e r" th Ira NEW WORLD TELEVISION GROUP 16 West 61st Street, 10th floor, New York, NY 10023 (212) 603 -7713, Telex: 428443 LCA, Fax: (212) 582-5167 All Marvd Comics Characters: TM & x_1987 Marvel Entertainment Group, Inc. All Rights Reserved. NATIONAL ADVERTISING SALES HANDLED BY TELETRIB (212) 750-9190 Hitch a ride on a proven winner! Number one in family one hour programs, HIGHWAY TO HEAVEN is quality entertainment the coun- try has taken to heart. It's everything you need to pave the way to programming success! NEW WORLD TELEVISION GROUP French Victor and Landon Michael Starring ( r Whey Do Radio Station Tow Call Americom? Americom closed over 80 percent of the listings we accepted in 1985 and 1986. Americom is consistently able to get high prices because we understand radio station values. Ask the former owners of WLIF(FM) Baltimore ( $25,000,000 cash), KIXL/KHFI Austin ( $25,000,000 cash), WSIX(AM/FM) Nashville ( $8,500,000), and KAPE/KESI San Antonio ( $9,270,000 cash). -

Investment in the Delivery of Effective Care to Help Improve Quality, Curb Costs

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Hearst Corporation Acquires Milliman Care Guidelines, LLC RE: Investment in the delivery of effective care to help improve quality, curb costs NEW YORK & SEATTLE, Nov. 5, 2012 — Hearst Corporation today signed an agreement with Milliman, Inc. pursuant to which Hearst will acquire Milliman Care Guidelines LLC, a leading provider of evidence-based clinical healthcare guidelines. The announcement was made by Frank A. Bennack, Jr., CEO of Hearst Corporation, and Richard P. Malloch, president of Hearst Business Media. Terms of the acquisition were not disclosed. The transaction is expected to close in Q4 following receipt of necessary government approvals. Used by more than 2,200 healthcare plans and health systems, Milliman Care Guidelines provides globally sourced, clinically validated guidelines and software to support the care management of most Americans. The company is the latest addition to Hearst’s expanding healthcare capabilities, which include Zynx Health and FDB (First Databank) — leaders in providing clinical decision support that helps providers plan and manage day-to-day patient care. Milliman Care Guidelines strengthens Hearst’s ability to provide critical, time-sensitive information to the healthcare industry. With a staff of 200, including 44 medical doctors and registered nurses, Milliman Care Guidelines compiles independent research on effective healthcare, citing more than 13,500 unique references as of 2012. Its Indicia™ product line for providers supports utilization review, case management, and care coordination, while its Cite™ product line for payors supports auto authorization, health management, and utilization management. The acquisition gives Milliman Care Guidelines a broader distribution channel for its products as well as access to Hearst’s rich information resources and expertise, which will help further strengthen the quality of its guidelines. -

Hearst Corporation - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Hearst Corporation - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hearst_Corporation Hearst Corporation From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia The Hearst Corporation is an American multinational conglomerate group based in the Hearst Tower in Hearst Corporation Midtown Manhattan, New York City. Founded by William Randolph Hearst as an owner of newspapers, the company has holdings that have subsequently expanded Type Private to include a highly diversified portfolio of media Industry Conglomerate[1] interests. The Hearst family is involved in the ownership Founded March 4, 1887 and management of the corporation. San Francisco, California, Hearst is one of the largest diversified communications United States companies in the world. Its major ownership interests Founder William Randolph Hearst include 15 daily and 36 weekly newspapers and more Headquarters Hearst Tower than 300 magazines worldwide, including Harper's Midtown Manhattan Bazaar, Cosmopolitan, Esquire, Elle, and O, The Oprah New York City, United States Magazine; 31 television stations through Hearst Key people William Randolph Hearst III Television, Inc., which reach a combined 20% of U.S. (Chairman) viewers; ownership in leading cable networks, including Frank A. Bennack, Jr. A+E Networks, and ESPN Inc.; as well as business (Executive Vice Chairman) publishing, digital distribution, television production, Steve Swartz newspaper features distribution, and real estate ventures. (President and CEO) Revenue US$ 10 billion (2014)[2][3] Contents Owner Hearst family -

Hearst@125/2012 Property List

HEARST@125/2012 x PROPERTY LIST NEWSPAPERS Northeast Herald (TX) Town & Country Albany Times Union (NY) Northwest Weekly (TX) Veranda Beaumont Enterprise (TX) Norwalk Citizen (CT) Woman’s Day Connecticut Post (CT) Our People (TX) Edwardsville Intelligencer (IL) Pennysaver News (NY) INTERNATIONAL MAGAZINE ACTIVITIES Greenwich Time (CT) Randolph Wingspread (TX) Hearst Magazines International Houston Chronicle (TX) Southside Reporter (TX) Australia Hearst/ACP (50% owned by Hearst) Huron Daily Tribune (MI) Spa City Moneysaver (NY) The Greater New Milford Spectrum (CT) Canada Laredo Morning Times (TX) Les Publications Transcontinental Midland Daily News (MI) The Zapata Times (TX) Hearst Inc. (49% owned by Hearst) Midland Reporter-Telegram (TX) Westport News (CT) China Beijing Hearst Advertising Co. Ltd. Plainview Daily Herald (TX) Wilton/Gansevoort/South Glens Falls Moneysaver (NY) Beijing MC Hearst Advertising Co. Ltd. San Antonio Express-News (TX) (49% owned by Hearst) San Francisco Chronicle (CA) DIRECTORIES COMPANY Beijing Trends Communications Co. Ltd. The Advocate, Stamford (CT) (20% owned by Hearst) LocalEdge The News-Times, Danbury (CT) Shanghai Next Idea Advertising Co., Ltd. Metrix4Media France WEBSITES Inter-Edi, S.A. (50% owned by Hearst) INVESTMENTS/ALLIANCES Seattlepi.com Germany Newspaper National Network, LP Elle Verlag GmbH (50% owned by Hearst) (5.75% owned by Hearst) Greece WEEKLY NEWSPAPERS NewsRight, LLC (7.2% owned by Hearst) Hearst DOL Publishing S.R.L. (50% owned by Hearst) Advertiser North (NY) quadrantONE, LLC (25% owned by Hearst) Advertiser South (NY) Hong Kong Wanderful Media, LLC SCMP Hearst Hong Kong Limited (12.5% owned by Hearst) Ballston Spa/Malta Pennysaver (NY) (30% owned by Hearst) Bulverde Community News (TX) SCMP Hearst Publications Ltd. -

Members of the Board of Directors Victor Rey, Jr

January 22, 2021 TO: Members of the Board of Directors Victor Rey, Jr. – President Regina M. Gage – Vice President Juan Cabrera – Secretary Richard Turner – Treasurer Joel Hernandez Laguna – Assistant Treasurer Legal Counsel Ottone Leach & Ray LLP News Media Salinas Californian Monterey County Herald El Sol Monterey County Weekly KION-TV KSBW-TV/ABC Central Coast KSMS/Entravision-TV The Regular Meeting of the Board of Directors of the Salinas Valley Memorial Healthcare System will be held THURSDAY, JANUARY 28, 2021, AT 4:00 P.M., IN THE CISLINI PLAZA BOARD ROOM IN SALINAS VALLEY MEMORIAL HOSPITAL, 450 E. ROMIE LANE, SALINAS, CALIFORNIA, OR BY PHONE OR VIDEO (Visit svmh.com/virtualboardmeeting for Access Information). Please note: Pursuant to Executive Order N-25-20 issued by the Governor of the State of California in response to concerns regarding COVID-19, Board Members of Salinas Valley Memorial Healthcare System, a local health care district, are permitted to participate in this duly noticed public meeting via teleconference and certain requirements of The Brown Act are suspended. Pete Delgado President/Chief Executive Officer Page 1 of 246 REGULAR MEETING OF THE BOARD OF DIRECTORS SALINAS VALLEY MEMORIAL HEALTHCARE SYSTEM THURSDAY, JANUARY 28, 2021 4:00 P.M. – CISLINI PLAZA BOARD ROOM SALINAS VALLEY MEMORIAL HOSPITAL 450 E. ROMIE LANE, SALINAS, CALIFORNIA OR BY PHONE OR VIDEO (Visit svmh.com/virtualboardmeeting for Access Information) Please note: Pursuant to Executive Order N-25-20 issued by the Governor of the State of California in response to concerns regarding COVID-19, Board Members of Salinas Valley Memorial Healthcare System, a local health care district, are permitted to participate in this duly noticed public meeting via teleconference and certain requirements of The Brown Act are suspended. -

Hearst Agrees to Acquire Camp Systems International Inc., a Leading Aviation Software-As-A-Service Company

News HEARST AGREES TO ACQUIRE CAMP SYSTEMS INTERNATIONAL INC., A LEADING AVIATION SOFTWARE-AS-A-SERVICE COMPANY NEW YORK, Oct. 26, 2016 — Hearst today announced it has agreed to acquire CAMP Systems International Inc. from private equity firm GTCR. CAMP is a leading global provider of software-as-a-service (“SaaS”) solutions for managing and tracking the maintenance of jets, turbo prop aircraft and helicopters used in business aviation, as well as enterprise information systems used to manage service centers. CAMP serves more than 19,000 aircraft, 30,000 engines and 1,300 maintenance facilities globally. Headquartered in Merrimack, New Hampshire, CAMP has 12 offices around the world. The announcement was made by Hearst President and CEO Steven R. Swartz, Hearst Business Media President Richard P. Malloch, and CAMP Systems International Inc. CEO Ken Gray. Terms were not disclosed. The transaction is expected to close by the end of 2016, subject to regulatory approvals. CAMP’s tracking software serves an essential market need as nearly all business aircraft owners require maintenance tracking software to comply with global regulations and guidelines, ensure aircraft safety and improve operating efficiency. Strategically, Hearst continues to diversify into data and information-based companies, while growing its world-class media assets. Commenting on the announcement, Swartz said: “Under CEO Ken Gray and President Vibby Gottemukkala, CAMP has an impressive record of growth and long-term customers that include the world’s leading business aircraft manufacturers. I’m excited about our future together and welcome Ken, Vibby and their colleagues to Hearst.” “We look forward to partnering with the CAMP team to capitalize on new opportunities to create more growth, expand its global reach and develop new offerings,” Malloch said. -

Hearst Health Invests in Health Optimization Pioneer Welltok

News HEARST HEALTH INVESTS IN HEALTH OPTIMIZATION PIONEER WELLTOK NEW YORK, January 8, 2015⎯Hearst Health, a unit of Hearst Corporation, announced a venture investment in Welltok, Inc., creator of the CaféWell platform, which allows insurers, hospitals and other health managers to work with consumers to help them achieve better health. The announcement was made by Richard P. Malloch, president of Hearst Business Media, the group that includes Hearst Health and its venture group, and Gregory Dorn, MD, president of Hearst Health. Financial terms of the investment were not disclosed. The Welltok platform helps people manage their own health with guidance that is tailored to their individual needs. Health plans and healthcare providers are able to incentivize and reward consumers for healthy activities. “Hearst Health Ventures is dedicated to advancing businesses that are providing innovative solutions to healthcare challenges,” Malloch said. “We are very pleased to work with Welltok and its outstanding management team.” Hearst Health Ventures takes minority positions in startups that offer health IT solutions and technology-enabled healthcare services. The healthcare venture fund is part of the Hearst Health network, which includes FDB (First Databank), Zynx Health, MCG and Homecare Homebase. "Across the Hearst Health network, we are committed to providing cutting-edge technology to deliver widespread access to vital information that improves health outcomes,” Dorn said. “Welltok’s groundbreaking platform allows consumers to take charge and personalize their health journey. We are excited to align with Welltok in this important endeavor.” As part of the investment, Ellen Koskinas, managing director of Hearst Health Ventures, will become an observer on the Welltok Board of Directors. -

Corporate Registry Registrar's Periodical Template

Service Alberta ____________________ Corporate Registry ____________________ Registrar’s Periodical REGISTRAR’S PERIODICAL, MAY 15, 2012 SERVICE ALBERTA Corporate Registrations, Incorporations, and Continuations (Business Corporations Act, Cemetery Companies Act, Companies Act, Cooperatives Act, Credit Union Act, Loan and Trust Corporations Act, Religious Societies’ Land Act, Rural Utilities Act, Societies Act, Partnership Act) 0713822 B.C. LTD. Other Prov/Territory Corps 1664177 ALBERTA LTD. Numbered Alberta Registered 2012 APR 12 Registered Address: #400 1111 Corporation Incorporated 2012 APR 10 Registered 11TH AVENUE SW, CALGARY ALBERTA, T2R Address: #300, 2912 MEMORIAL DRIVE S.E., 0G5. No: 2116710498. CALGARY ALBERTA, T2A 6R1. No: 2016641777. 0843008 B.C. LTD. Other Prov/Territory Corps 1666355 ALBERTA LTD. Numbered Alberta Registered 2012 APR 12 Registered Address: P.O. BOX Corporation Incorporated 2012 APR 10 Registered 473, NW 19-21-14-W4, DUCHESS ALBERTA, T0J Address: 128 BAYSIDE LANDING SW, AIRDRIE 0Z0. No: 2116710506. ALBERTA, T4B 3E3. No: 2016663557. 0933341 B.C. LTD. Other Prov/Territory Corps 1667789 ALBERTA LTD. Numbered Alberta Registered 2012 APR 11 Registered Address: BOX Corporation Incorporated 2012 APR 03 Registered 7649, 5108 53 STREET, DRAYTON VALLEY Address: 27 PANATELLA ROW NW, CALGARY ALBERTA, T7A 1S2. No: 2116707387. ALBERTA, T3K 0V5. No: 2016677896. 0937049 B.C. LTD. Other Prov/Territory Corps 1668479 ALBERTA LTD. Numbered Alberta Registered 2012 APR 04 Registered Address: SUITE Corporation Incorporated 2012 APR 02 Registered 204, 205-9TH AVENUE S.E., CALGARY ALBERTA, Address: 3702 DOVER RIDGE DRIVE SE, CALGARY T2G 0R3. No: 2116696374. ALBERTA, T2B 2C8. No: 2016684793. 0937751 B.C. LTD. Other Prov/Territory Corps 1668482 ALBERTA LTD. -

Hearst Corporation Milestones Under Leadership of Frank A. Bennack, Jr

Hearst Corporation Milestones Under Leadership of Frank A. Bennack, Jr. (1979-2013) 1980: Hearst acquires First Databank Inc. 1981: Hearst is a founding partner in the precursors of cable networks A&E and Lifetime with ABC. 1986: Hearst acquires Boston’s WCVB-TV. 1987: Houston Chronicle is purchased by Hearst. 1990: Hearst acquires 20 percent interest in ESPN. 1997: Hearst combines its stations with Argyle Television’s stations to form Hearst-Argyle Television, Inc., a publicly traded company. 1999: Hearst-Argyle completes acquisition of Pulitzer’s broadcasting group. 2000: O, The Oprah Magazine is the industry’s most successful magazine launch. 2000: Hearst purchases the San Francisco Chronicle. 2006: Hearst acquires a 20 percent equity interest in global ratings agency Fitch Group. 2006: Hearst Tower opens and is certified as the city’s first occupied “green” office building with a Gold LEED Rating. (Building process started in October 2001; Hearst was first NY company to commit to new building project after 9/11.) 2008: Hearst acquires the Connecticut Post. 2008: Hearst and Food Network introduce Food Network Magazine. 2009: Hearst increases its equity interest in Fitch Group from 20 to 40 percent. 2009: Hearst acquires outstanding publicly traded shares of Hearst-Argyle Television, creating Hearst Television Inc., a private company. 2010: Hearst acquires global digital marketing services company iCrossing. 2011: Hearst and Mark Burnett announce the formation of a long-term joint venture, One Three Media. 2011: Hearst acquires nearly 100 titles in 14 countries from Lagardère. (U.S. titles include Car and Driver, ELLE, ELLE DECOR, Road & Track and Woman’s Day.) 2011: Hearst and HGTV introduce HGTV Magazine.