The Value of U.S. Downtowns and Center Cities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Effective January 24, 2021 LIMITED EXPRESS ROUTES LOCAL

WESLEY CHAPELCHAPEL LOCAL ROUTES Calusa Tr ace BlBlv & HARTFLEX vdd.. Van Dyke RdRd.. St. Joseph’s Hospital - North ALL SERVICE MAPS LOCAL ONLY EXPRESS ONLY 33 WESLEY CHAPELCHAPEL NORTHDALE Lakeview D r . LUTZ SYSTEM MAP Gaither High TAMPA PALMS School Effective January 24, 2021 NNoorthda le B lv d. e. Sinclair Hills Rd. e. Av Av LEGEND LEGEND LEGEND Be . ars d s v l A Local Route Key Destinations Key Destinations B Ehrlich Rd. v s B 44 e n # and Route Number . w Route 33 does not 22nd St. 22nd St. Livingston Livingston ce BB. Do Hidden Local Route and Route Number Express Route Bru serve Hidden River 12 Calusa Skipper Rd.Rd. River Limited Express Route 20X20X Express routes marked by an X Tr Park-n-Ride on Park-n-Riderk-n-Ride ace BlvBl 44 AdventHealthventHealth Weekends # and Route Number Downtown to UATC CITRUS PARK vdd.. 1 42 400 Westeldsteld Fletcher Ave. 42 - Tampa 33 LX Limited Express routes See route schedule for details Limited Express Route Citrus Park @ Dale MabMabrryy Hwy. Stop P marked by an LX 75LX Mall Van Dyke RdRd.. 33 6 Fletcher Ave. Limited Express routes marked by an LX HARTFlex Zone St. Joseph’s Fletcher Ave. 33 400 FLEX e. HospitalCARROLLWOOCARROLLWOOD - North D e. 33 HARTFlex Route See route schedule for details 39 GunnGun H 48 Park-n-Ride Lots Av n Hwwy. 33 Av y. 131st Ave. University P B HARTFleHARTFlexx HARTFlex Route Vanpool Option Locations Walmart of South HARTFlex Zone See route schedule for details NORTHDALE Lakeview 45 Call TBARTA at (800) 998-RIDE (7433) e. -

West End Tampa Tampa, Florida

West End Tampa Tampa, Florida MORIN DEVELOPMENT GROUP 1510 West Cleveland Street, Tampa FL 33606 Telephone 813-258-2958 Fax 813-258-2959 1 The information above has been obtained from sources believed reliable. While we do not doubt its accuracy we have not verified it and make no guarantee, warranty or representation about it. It is your responsibility to independently confirm its accuracy and completeness. Table of Contents • Development Summary • Site Plans • Block A • Block B • Block C • Block D • Block E • Block F • Block G • North B Town Homes • Market Information • About Us 2 West End Tampa West End Tampa is a 20-acre master planned, family community comprised of apartments, town homes, condominiums and retail features. It is centrally located between the region’ s two largest business centers – Downtown Tampa (within 1 mile) and the West Shore Business District (within 3 miles). West End is encircled by major medical centers including Tampa General, Memorial and St. Joseph’s hospitals. It is situated within blocks of the nationally accredited University of Tampa. The West End community incorporates architectural sensitivity with ample, open public spaces to create a livinggyg environment that is distinctly different from the existing inventory of “Urban Lifestyle” product which is prevalent today. Contributing to the lifestyle balance of West End Tampa are parks, public art, recreational areas, pools, fitness centers and a convenient business center. Retail and Commercial…………………….25,000 Sq. Ft. of “neighborhood retail” spacece Office………………………………………...4, 500 Sq. Ft. of “Class A ” office space UNITS HEIGHT BEDROOMS SQ. FT. Condominiums 346 4-5 stories 2 & 3 630 – 1,600 Town Homes 79 3stories3 stories 2&32 & 3 16231,623 – 21132,113 Apartments 3 The Vintage Lofts 249 4 stories 1, 2 & 3 740 – 1,250 Logan Park 296 8 stories 1 & 2 737 – 1,204 West End Location West End Tampa is bordered to the south by Tampa’s charming Hyde Park neighborhood. -

The Elliman Report: Q3-2020 Tampa Sales Prepared by Miller Samuel Real Estate Appraisers

Report South And Greater Q3-2020 Downtown Tampa, FL Sales Median Sales Price South Tampa Single Family Number of Sales $400K 400 $320K 320 South Tampa $240K 240 Single Family $160K 160 Dashboard $80K 80 YEAR-OVER-YEAR Median Sales Price South Tampa Single Family Number of Sales $0 0 $400K 400 + 11.2% 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 $320KSouth Tampa Single Family Matrix Q3-2020 %∆ (QTR) Q2-2020 %∆ (YR) Q3-2019320 Prices Median Sales Price Average Sales Price $440,254 8.3% $406,697 13.7% $387,263 $240K 240 + 22.8% Average Price Per Sq Ft $224 1.4% $221 7.2% $209 $160KMedian Sales Price South Tampa Condo Number of Sales160 Sales Closed Sales Median Sales Price $358,750 10.6% $324,500 11.2% $322,500 $250KNumber$80K of Sales (Closed) 334 36.9% 244 22.8% 2728060 - 31.7% Days on Market (From Last List Date) 38 -20.8% 48 -29.6% 54 $200K$0 048 Inventory Tota l Inventor y Listing Discount (From Last List Price) 1.7% 2.4% 2.0% 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 $150KListing Inventory 127 0.8% 126 -31.7% 18636 - 16 days $100KMonths of Supply 1.1 -26.7% 1.5 -47.6% 2.124 Marketing Time Average Square Feet 1,962 6.3% 1,845 5.9% 1,853 Days on Market $50K 12 Median Sales Price South Tampa Condo Number of Sales $0 0 $250K 60 South Tampa Condo 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 Dashboard $200K 48 YEAR-OVER-YEAR $150K 36 + 34.1% $100K 24 Median Sales Price Number of Sales Prices Median Sales Price $50K South Tampa Luxury 12 $1.1M 50 + 10.6% $0 0 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 -

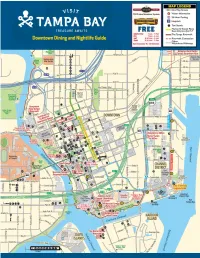

Downtown Dining Map 2019 List

To 13 51 136 137 118 138 114 17 157 123 25 23 41 154 91 10 101 98 76 45 61 83 18 149 143 2 76 86 16 26 55 105 94 14 103 56 128 109 80 48 111 8 2 77 96 104 78 74 93 28 46 99 141 53 40 1 38 7 32 97 5 153 3 146 21 39 95 134 4 66 47 106 21 90 9 59 79 102 44 72 92 58 121 120 87 70 151 127 135 69 60 82 122 124 114 115 68 100 85 120 41 125 43 117 84 88 119 71 73 140 73 12 35 64 75 20 42 34 To 27 15 29 33 24 17 156 126 19 To 52 63 158 159 37 129 152 30 81 6 147 107 155 89 To 133 11 22 139 50 132 148 131 To 130 31 36 49 62 65 110 112 AMERICAN 152 Publix Super Market on Bayshore Bakery- 87 Kahwa Café, Rivergate Tower - 17 Precinct Pizza - 813.228.6973 813.251.1173 813.225.2040 43 211 Restaurant at Hilton Tampa Downtown 96 Riverwalk Cafe at TMA - 813.421.8367 813.204.3000 BARBEQUE 66 Moxies Café - 813.221.4510 80 Tampa Pizza Co., SkyPoint - 813.463.1600 130 220 East - 813.259.1220 44 Holy Hog Barbecue - 813.223.4464 68 Nature’s Table, Park Tower - 813.223.2233 12 TamPiz - 813.252.3420 131 725 South Bistro at Westin Tampa 69 Oasis Deli - 813.223.3305 Waterside - 813.229.5000 CARIBBEAN 60 Toscanini NY Pizza and Pita - 813.500.7700 70 Ole Style Deli - 813.223-4282 97 1895 Kitchen Bar Market - 813.375.9995 34 Caribbean Cantina in Florida Aquarium - 813.273.4000 59 Pokeys - 813.223.6905 MEDITERRANEAN 132 American Social - 813.605.3333 40 Jerk Hut Downtown Café - 813.223.5375 152 Publix Deli - 813.251.1173 56 Falafel Inn Mediterranean Grill, SkyPoint - 124 Brightside Cafe - 813.241.9295 813.223.5800 84 Surf & Turf Cafe - 813.221.3354 98 Bistro at The -

City of Tampa Walk–Bike Plan Phase VI West Tampa Multimodal Plan September 2018

City of Tampa Walk–Bike Plan Phase VI West Tampa Multimodal Plan September 2018 Completed For: In Cooperation with: Hillsborough County Metropolitan Planning Organization City of Tampa, Transportation Division 601 East Kennedy Boulevard, 18th Floor 306 East Jackson Street, 6th Floor East Tampa, FL 33601 Tampa, FL 33602 Task Authorization: TOA – 09 Prepared By: Tindale Oliver 1000 N Ashley Drive, Suite 400 Tampa, FL 33602 The preparation of this report has been financed in part through grants from the Federal Highway Administration and Federal Transit Administration, U.S. Department of Transportation, under the Metropolitan Planning Program, Section 104(f) of Title 23, U.S. Code. The contents of this report do not necessarily reflect the official views or policy of the U.S. Department of Transportation. The MPO does not discriminate in any of its programs or services. Public participation is solicited by the MPO without regard to race, color, national origin, sex, age, disability, family or religious status. Learn more about our commitment to nondiscrimination and diversity by contacting our Title VI/Nondiscrimination Coordinator, Johnny Wong at (813) 273‐3774 ext. 370 or [email protected]. WEST TAMPA MULTIMODAL PLAN Table of Contents Executive Summary ........................................................................................................................................................................................................ 1 Introduction and Purpose ......................................................................................................................................................................................... -

Tampa Bay History Published Through a Partnership Between the Tampa Bay History Center and the University of South Florida Libraries’ Florida Studies Center

Volume 23 2009 Tampa Bay History Published through a partnership between the Tampa Bay History Center and the University of South Florida Libraries’ Florida Studies Center Rodney Kite-Powell, Editor Saunders Foundation Curator of History, Tampa Bay History Center Andrew Huse, Assistant Editor Assistant Librarian, University of South Florida Libraries’ Special Collections Department and Florida Studies Center Mark I. Greenberg, Ph.D., Book Review Editor Director, University of South Florida Libraries’ Special Collections Department and Florida Studies Center Editorial Board Jack Davis, Ph.D. University of Florida James M. Denham, Ph.D. Florida Southern College Paul Dosal, Ph.D. University of South Florida Maxine Jones, Ph.D. Florida State University Robert Kerstein, Ph.D. University of Tampa Joe Knetsch, Ph.D. State of Florida, Department of Environmental Protection Jerald Milanich, Ph.D. Florida Museum of Natural History Gary R. Mormino, Ph.D. Florida Studies Program, University of South Florida Susan Parker, Ph.D. St. Augustine Historical Society Cheryl Rodriguez, Ph.D. University of South Florida Aaron Smith, Ph.D. University of South Florida Doris Weatherford Tampa, Florida Tampa Bay History (ISSN: 0272-1406) is published annually through a partnership between the Tampa Bay History Center and the Florida Studies Center at the University of South Florida Library. The journal is provided complimentarily to Tampa Bay History Center members who belong at or above the Supporter membership level. Copies of the current issue of Tampa Bay History may be purchased directly from the Tampa Bay History Center at a cost of $19.95, plus shipping. Back issues (beginning with the 2007 issue) will also be available for purchase. -

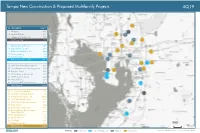

Tampa New Construction & Proposed Multifamily Projects

Tampa New Construction & Proposed Multifamily Projects 4Q19 ID PROPERTY UNITS 1 Wildgrass 321 3 Union on Fletcher 217 5 Harbour at Westshore, The 192 Total Lease Up 730 15 Bowery Bayside Phase II 589 16 Tapestry Town Center 287 17 Pointe on Westshore, The 444 28 Victory Landing 69 29 Belmont Glen 75 Total Under Construction 1,464 36 Westshore Plaza Redevelopment 500 37 Leisey Road Mixed Used Development 380 38 Progress Village 291 39 Grand Cypress Apartments 324 43 MetWest International 424 44 Waverly Terrace 214 45 University Mall Redevelopment 100 Total Planned 2,233 69 3011 West Gandy Blvd 80 74 Westshore Crossing Phase II 72 76 Village at Crosstown, The 3,000 83 3015 North Rocky Point 180 84 6370 North Nebraska Avenue 114 85 Kirby Street 100 86 Bowels Road Mixed-Use 101 87 Bruce B Downs Blvd & Tampa Palms Blvd West 252 88 Brandon Preserve 200 89 Lemon Avenue 88 90 City Edge 120 117 NoHo Residential 218 Total Prospective 4,525 2 mi Source: Yardi Matrix LEGEND Lease-Up Under Construction Planned Prospective Tampa New Construction & Proposed Multifamily Projects 4Q19 ID PROPERTY UNITS 4 Central on Orange Lake, The 85 6 Main Street Landing 80 13 Sawgrass Creek Phase II 143 Total Lease Up 308 20 Meres Crossing 236 21 Haven at Hunter's Lake, The 241 Total Under Construction 477 54 Bexley North - Parcel 5 Phase 1 208 55 Cypress Town Center 230 56 Enclave at Wesley Chapel 142 57 Trinity Pines Preserve Townhomes 60 58 Spring Center 750 Total Planned 1,390 108 Arbours at Saddle Oaks 264 109 Lexington Oaks Plaza 200 110 Trillium Blvd 160 111 -

Downtown Tampa Florida

DOWNTOWN TAMPA FLORIDA 2016 - Downtown Tampa is HAPPENING! Shovels turning dirt, red cranes a constant in the skyline, large scale development projects announced with regularity, commercial office towers sold at record prices, and ceremonial ribbons being cut as private and public development/investments soar to an all-time high! PUBLIC SPACES Tampa Riverwalk - The Kennedy Riverwalk Segment opened in early 2015, resulting in 2.2 miles of contiguous urban waterfront walkway Selmon Greenway - Bicycle and pedestrian path opened in early 2015 Water Works Park - Opened Summer 2014 Julian B. Lane Riverfront Park - Master planning process in 2014 TRANSPORTATION & LAND USE PLANNING Public and Private Sector Plans guiding community growth Imagine Hillsborough 2040 Long Range Transportation Plan (2015) Downtown Transit Assets & Opportunities (2014) Tampa Historic Streetcar Extension Study (2014) Port Tampa Bay Vision (Unveiled 2015) – 45 acres SPP Tampa Bay Waterfront 2020 Vision (Unveiled 2014) – 40 acres RESIDENTIAL – Supply and demand on the rise +1,500 Newly Opened Units 2012-2016 - Crescent Bayshore | NoHo Flats Pierhouse Channelside | ENCORE!® | The Aurora | SkyHouse Channelside Madison Heights +4,500 Planned /Under Construction Units - 500 Harbour Island |The Aurora The Fitzgerald | The Channel Club (with Publix Grocery) |AER | NINE 15 The Heights | The Manor | NoHo Flats II | Related Group’s Tribune Site Feldman Equities/Tower Realty ‘s Riverwalk Tower| Gas Worx | Riverwalk Tower Port Tampa Bay Vision | SPP Waterfront Vision HOTELS 2 - New (adaptive reuse) 1 - Planned 4 - Renovations Le Méridien Tampa - Opened June 2014, 130-room hotel converted from 109 year old Federal Courthouse Aloft Tampa Downtown - Opened July 2014, 130-room riverfront hotel converted from old Mercantile Bank Planned - 400-room hotel adjacent to Amalie Arena MARKETPLACE New and expanding retail, restaurants, and personal service businesses opening to meet the demand of growing residential and visitor populations. -

Earl of Sanwhich Downtown Tampa

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact: Mary Lou Janson, [email protected] THE SANDWICHES ARE COMING TO DOWNTOWN TAMPA! Earl of Sandwich – the “World’s Greatest Hot Sandwich®”– Opens on North Tampa Street at Element Apartments May 31 Tampa, FL, (May 22, 2017) – Earl of Sandwich, a globally-recognized, fast casual restaurant that features fresh, made-to-order sandwiches and other treats, opens May 31 at 811 N. Tampa Street. Inspired by John Montagu, the 4th Earl of Sandwich who invented the sandwich in 1762, the location is the fourth to open in the Tampa Bay area and a great addition to Tampa’s vibrant downtown business center and residential developments. The new Earl of Sandwich joins the Earl of Sandwich located at International Plaza in Tampa, the Earl of Sandwich at the Royal Palms Shopping Center on 4th St. North in St. Petersburg and another location that opened at Bayport Commons May 9 at 11721 W. Hillsborough Ave. “I am thrilled that Earl of Sandwich is opening in downtown Tampa,” said Robert Earl, a founding partner of Earl of Sandwich and founder and CEO of Planet Hollywood®. “We are excited to be part the downtown community that includes museums, performing arts venues, athletic events and festivals held throughout the year. We are pleased to offer the same delicious gourmet sandwiches and salads and wraps that make Earl of Sandwich a popular place to dine, carry out, or for any catering needs.” At the heart of the menu is the World’s Greatest Hot Sandwich®, an appetizing assortment of signature hot sandwiches made by hand and made to order using the best quality ingredients and served on warm artisan bread. -

Tampa New Construction & Proposed Multifamily Projects 1Q20

Tampa New Construction & Proposed Multifamily Projects 1Q20 ID PROPERTY UNITS 128 1 Icaria on Pinellas 236 129 130 4 Addison at Sunlake, The 307 5 Union on Fletcher 217 10 Parc at Wesley Chapel 248 13 Central on Orange Lake, The 85 122 17 Sawgrass Creek Phase II 143 Total Lease Up 1,236 30 Notch 112 31 Haven at Hunter's Lake, The 241 35 Altis @ Preserve 350 Total Under Construction 703 49 Waverly Terrace 214 50 University Mall Redevelopment 100 55 Bridge Haven 100 120 56 Cypress Town Center 230 126 57 Central on Orange Lake, The Phase II 50 13 Total Planned 694 124 57 10 119 121 92 Kirby Street 100 17 125 93 Bowels Road Mixed-Use 101 94 Bruce B Downs Blvd & Tampa Palms Blvd West 252 4 55 56 35 123 95 East Fowler Avenue 292 127 119 Arbours at Saddle Oaks 264 120 Bexley North - Parcel 5 Phase 1 208 121 Lexington Oaks Plaza 200 1 31 122 Trillium Blvd 160 133 123 Wiregrass 249 124 Summerset Senior 86 125 Wyndrush Townhomes 106 94 126 Cotee River 240 Honeymoon 127 Trinity Pines Preserve Townhomes 60 Island 5 State Park 50 128 Forest Oaks Boulevard 117 Temporarily 95 129 Spring Center 750 Closed 130 Spring Center Phase II 750 49 93 133 Venetian Isles 86 92 30 Total Prospective 4021 2 mi Source: Yardi Matrix LEGEND Lease-Up Under Construction Planned Prospective Tampa New Construction & Proposed Multifamily Projects 1Q20 Caladesi Island State Park Philippe Park 111 ID PROPERTY UNITS 74 12 Harbour at Westshore, The 192 15 1100 Apex 134 91 Total Lease Up 326 110 15 90 28 22 Grove Isle 298 72 24 Cortland Westshore 589 71 27 Pointe on Westshore, The 444 28 Novel Midtown Tampa 390 St. -

The Tampa Center City Plan Connecting Our Neighborhoods and Our River for Our Future

The Tampa Center City Plan Connecting Our Neighborhoods and Our River for Our Future The Tampa Center City Plan Connecting Our Neighborhoods and Our River for Our Future NOvembeR 2012 Prepared for: City of Tampa IMAGE PLACEHOLDER Prepared by: AECOM 150 North Orange Avenue Orlando, Florida 32801 407 843 6552 AECOM Project No. : 60250712 AECOM Contact : [email protected] In Collaboration With: Parsons Brinckerhoff The Leytham Group ChappellRoberts Blackmon Roberts Group MindMixer Crossroads Engineering Fowler White Boggs PA Stephanie Ferrell FAIA Architect Martin Stone Consulting, LLC © AeCOm Technical Services 2012 This document has been prepared by AeCOm on behalf of the City of Tampa, Florida. This project was made possible through a Sustainable Communities Challenge Grant provided by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. Participation List City Team Workshop Participants bob buckhorn - Mayor Chris Ahern Duncan broyd David Crawley bruce earhart bob mcDonaugh - Economic Development Administrator Art Akins Rod brylawski Nelson Crawley Shannon edge Thomas Snelling - Planning & Development Director Catherine Coyle - Planning Manager Adjoa Akofio-Swah bob buckhorn Darryl Creighton Diane egner Randy Goers - Project Manager beth Alden Arnold buckley Jim Crews Chris elmore J.J. Alexander benjamin buckley Laura Crews michael english Consultant Team Albert Alfonso michelle buckley Daryl Croi maggie enncking Robert Allen Davis burdick Andrea Cullen James evans AECOM ChappellRoberts Joseph Alvarez Andy bushnell Wence Cunnigham -

Citrus County

LEGAL ADVERTISEMENT LEGAL ADVERTISEMENT LEGAL ADVERTISEMENT LEGAL ADVERTISEMENT LEGAL ADVERTISEMENT CITRUS COUNTY CITRUS COUNTY CITRUS COUNTY HERNANDO COUNTY HERNANDO COUNTY CITRUS COUNTY COUNTY, FLORIDA FGHGPUGUKHCP[VQKVQP2NCKPVKHHUŏCVVQTPG[ C(NQTKFC.KOKVGF.KCDKNKV[%QORCP[ FGEGFGPVŏUGUVCVGQPYJQOCEQR[QHVJKU PROBATE DIVISION Donald F. Perrin, Esq., DONALD F. PER- Plaintiff, PQVKEG KU TGSWKTGF VQ DG UGTXGF OWUV ſNG File No. 2020-CP- 000424 4+02#2QUV1HſEG$QZ+PXGTPGUU v. their claims with this court ON OR BEFORE (.YKVJKPHQTV[ FC[UCHVGT THE LATER OF 3 MONTHS AFTER THE IN THE CIRCUIT COURT OF THE Division Probate VJG ſTUV RWDNKECVKQP QH VJKU PQVKEG CPF ſNG LUIS E. DUMOIS and JOSEFA NUNEZ TIME OF THE FIRST PUBLICATION OF FIFTH JUDICIAL CIRCUIT IN AND FOR DE DUMOIS, IN RE: ESTATE OF the original with the Clerk of this Court ei- THIS NOTICE OR 30 DAYS AFTER THE CITRUS COUNTY, FLORIDA VJGTDGHQTGUGTXKEGQP2NCKPVKHHŏUCVVQTPG[QT Defendants. DATE OF SERVICE OF A COPY OF THIS GALE R. MORIN, CIVIL DIVISION KOOGFKCVGN[VJGTGCHVGTQVJGTYKUGCFGHCWNV NOTICE OF ACTION NOTICE ON THEM. Case Number: 2021CA00276A Deceased. YKNNDGGPVGTGFCICKPUV[QWHQTVJGTGNKGHFG- TO: LUIS E. DUMOIS and JOSEFA All other creditors of the decedent and OCPFGFKPVJG%QORNCKPV QVJGT RGTUQPU JCXKPI ENCKOU QT FGOCPFU HERBERT H. SHARPE and NOTICE TO CREDITORS NUNEZ DE DUMOIS, '&VJKUVJFC[QH,WPG (Address Unknown) CICKPUV FGEGFGPVŏU GUVCVG OWUV ſNG VJGKT SALLY-ANNE SHARPE, The administration of the estate of claims with this court WITHIN 3 MONTHS Plaintiff, GALE R. MORIN, deceased, whose date ANGELA VICK Clerk of the Court YOU ARE NOTIFIED that an action to AFTER THE DATE OF THE FIRST PUB- v. QHFGCVJYCU,WPG(KNG0WODGT quiet title to the following described real LICATION OF THIS NOTICE.