Dihydrogen Complexes As Prototypes for the Coordination Chemistry of Saturated Molecules

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Indicator of Triplet State Baird-Aromaticity

inorganics Article The Silacyclobutene Ring: An Indicator of Triplet State Baird-Aromaticity Rabia Ayub 1,2, Kjell Jorner 1,2 ID and Henrik Ottosson 1,2,* 1 Department of Chemistry—BMC, Uppsala University, Box 576, SE-751 23 Uppsala, Sweden; [email protected] (R.A.); [email protected] (K.J.) 2 Department of Chemistry-Ångström Laboratory Uppsala University, Box 523, SE-751 20 Uppsala, Sweden * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +46-18-4717476 Received: 23 October 2017; Accepted: 11 December 2017; Published: 15 December 2017 Abstract: Baird’s rule tells that the electron counts for aromaticity and antiaromaticity in the first ππ* triplet and singlet excited states (T1 and S1) are opposite to those in the ground state (S0). Our hypothesis is that a silacyclobutene (SCB) ring fused with a [4n]annulene will remain closed in the T1 state so as to retain T1 aromaticity of the annulene while it will ring-open when fused to a [4n + 2]annulene in order to alleviate T1 antiaromaticity. This feature should allow the SCB ring to function as an indicator for triplet state aromaticity. Quantum chemical calculations of energy and (anti)aromaticity changes along the reaction paths in the T1 state support our hypothesis. The SCB ring should indicate T1 aromaticity of [4n]annulenes by being photoinert except when fused to cyclobutadiene, where it ring-opens due to ring-strain relief. Keywords: Baird’s rule; computational chemistry; excited state aromaticity; Photostability 1. Introduction Baird showed in 1972 that the rules for aromaticity and antiaromaticity of annulenes are reversed in the lowest ππ* triplet state (T1) when compared to Hückel’s rule for the electronic ground state (S0)[1–3]. -

Graphene Supported Rhodium Nanoparticles for Enhanced Electrocatalytic Hydrogen Evolution Reaction Ameerunisha Begum1*, Moumita Bose2 & Golam Moula2

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Graphene Supported Rhodium Nanoparticles for Enhanced Electrocatalytic Hydrogen Evolution Reaction Ameerunisha Begum1*, Moumita Bose2 & Golam Moula2 Current research on catalysts for proton exchange membrane fuel cells (PEMFC) is based on obtaining higher catalytic activity than platinum particle catalysts on porous carbon. In search of a more sustainable catalyst other than platinum for the catalytic conversion of water to hydrogen gas, a series of nanoparticles of transition metals viz., Rh, Co, Fe, Pt and their composites with functionalized graphene such as RhNPs@f-graphene, CoNPs@f-graphene, PtNPs@f-graphene were synthesized and characterized by SEM and TEM techniques. The SEM analysis indicates that the texture of RhNPs@f- graphene resemble the dispersion of water droplets on lotus leaf. TEM analysis indicates that RhNPs of <10 nm diameter are dispersed on the surface of f-graphene. The air-stable NPs and nanocomposites were used as electrocatalyts for conversion of acidic water to hydrogen gas. The composite RhNPs@f- graphene catalyses hydrogen gas evolution from water containing p-toluene sulphonic acid (p-TsOH) at an onset reduction potential, Ep, −0.117 V which is less than that of PtNPs@f-graphene (Ep, −0.380 V) under identical experimental conditions whereas the onset potential of CoNPs@f-graphene was at Ep, −0.97 V and the FeNPs@f-graphene displayed onset potential at Ep, −1.58 V. The pure rhodium nanoparticles, RhNPs also electrocatalyse at Ep, −0.186 V compared with that of PtNPs at Ep, −0.36 V and that of CoNPs at Ep, −0.98 V. -

Developing a S Ystem to Study the Dynamics of the Heterolysis of Psubstituted Radicals in Terms of Magnetic Field Effects

Developing a S ystem to Study the Dynamics of the Heterolysis of PSubstituted Radicals in terms of Magnetic Field Effects by Elaine K. Adams Submitted in partial fulfiiIlment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science Dalhousie University Halifax, Nova Scotia September, 1998 @ Copyright by Elaine K. Adams, 1998 National hirary Bibliothèque nationale du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisiins et Biliograpfii Services seMces bibliographiques The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant à la National Library of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or seli reproduire, prêter, distriiuer ou copies of this thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de micro fi ch el^ de reproduction sur papier ou sur fonnat électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts fkom it Ni la thése ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. Table of Contents List of Figures ........................................................................................ vi ... List of Tables ........................................................................................ xm 1.1 General Introduction ....................................................................... -

![Anagostic Interactions Under Pressure: Attractive Or Repulsive? Wolfgang Scherer *[A], Andrew C](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5995/anagostic-interactions-under-pressure-attractive-or-repulsive-wolfgang-scherer-a-andrew-c-885995.webp)

Anagostic Interactions Under Pressure: Attractive Or Repulsive? Wolfgang Scherer *[A], Andrew C

Manuscript Click here to download Manuscript: manuscript_final.pdf ((Attractive or repulsive?)) DOI: 10.1002/anie.200((will be filled in by the editorial staff)) Anagostic Interactions under Pressure: Attractive or Repulsive? Wolfgang Scherer *[a], Andrew C. Dunbar [a], José E. Barquera-Lozada [a], Dominik Schmitz [a], Georg Eickerling [a], Daniel Kratzert [b], Dietmar Stalke [b], Arianna Lanza [c,d], Piero Macchi*[c], Nicola P. M. Casati [d], Jihaan Ebad-Allah [a] and Christine Kuntscher [a] The term “anagostic interactions” was coined in 1990 by Lippard preagostic interactions are considered to lack any “involvement of 2 and coworkers to distinguish sterically enforced M•••H-C contacts dz orbitals in M•••H-C interactions” and rely mainly on M(dxz, yz) (M = Pd, Pt) in square-planar transition metal d8 complexes from o V (C-H) S-back donation.[3b] attractive, agostic interactions.[1a] This classification raised the fundamental question whether axial M•••H-C interaction in planar The first observation of unusual axial M•••H-C interaction in 8 8 d -ML4 complexes represent (i) repulsive anagostic 3c-4e M•••H-C planar d -ML4 complexes was made by S. Trofimenko, who interactions[1] (Scheme 1a) or (ii) attractive 3c-4e M•••H-C pioneered the chemistry of transition metal pyrazolylborato hydrogen bonds[2] (Scheme 1b) in which the transition metal plays complexes.[5,6] Trofimenko also realized in 1968, on the basis of the role of a hydrogen-bond acceptor (Scheme 1b). The latter NMR studies, that the shift of the pseudo axial methylene protons in 3 bonding description is related to another bonding concept which the agostic species [Mo{Et2B(pz)2}(K -allyl)(CO)2] (1) (pz = describes these M•••H-C contacts in terms of (iii) pregostic or pyrazolyl; allyl = H2CCHCH2) “is comparable in magnitude but [3] preagostic interactions (Scheme 1c) which are considered as being different in direction from that observed in Ni[Et2B(pz)2]2” (2) “on the way to becoming agostic, or agostic of the weak type”.[4] (Scheme 2).[6,7] Scheme 1. -

Coordinate Covalent C F B Bonding in Phenylborates and Latent Formation of Phenyl Anions from Phenylboronic Acid†

J. Phys. Chem. A 2006, 110, 1295-1304 1295 Coordinate Covalent C f B Bonding in Phenylborates and Latent Formation of Phenyl Anions from Phenylboronic Acid† Rainer Glaser* and Nathan Knotts Department of Chemistry, UniVersity of MissourisColumbia, Columbia, Missouri 65211 ReceiVed: July 4, 2005; In Final Form: August 8, 2005 The results are reported of a theoretical study of the addition of small nucleophiles Nu- (HO-,F-)to - phenylboronic acid Ph-B(OH)2 and of the stability of the resulting complexes [Ph-B(OH)2Nu] with regard - - - - - to Ph-B heterolysis [Ph-B(OH)2Nu] f Ph + B(OH)2Nu as well as Nu /Ph substitution [Ph-B(OH)2Nu] - - - + Nu f Ph + [B(OH)2Nu2] . These reactions are of fundamental importance for the Suzuki-Miyaura cross-coupling reaction and many other processes in chemistry and biology that involve phenylboronic acids. The species were characterized by potential energy surface analysis (B3LYP/6-31+G*), examined by electronic structure analysis (B3LYP/6-311++G**), and reaction energies (CCSD/6-311++G**) and solvation energies - (PCM and IPCM, B3LYP/6-311++G**) were determined. It is shown that Ph-B bonding in [Ph-B(OH)2Nu] is coordinate covalent and rather weak (<50 kcal‚mol-1). The coordinate covalent bonding is large enough to inhibit unimolecular dissociation and bimolecular nucleophile-assisted phenyl anion liberation is slowed greatly by the negative charge on the borate’s periphery. The latter is the major reason for the extraordinary differences in the kinetic stabilities of diazonium ions and borates in nucleophilic substitution reactions despite their rather similar coordinate covalent bond strengths. -

Hydrogen Peroxide As a Hydride Donor and Reductant Under Biologically Relevant Conditions† Cite This: Chem

Chemical Science View Article Online EDGE ARTICLE View Journal | View Issue Hydrogen peroxide as a hydride donor and reductant under biologically relevant conditions† Cite this: Chem. Sci.,2019,10,2025 ab d c All publication charges for this article Yamin Htet, Zhuomin Lu, Sunia A. Trauger have been paid for by the Royal Society and Andrew G. Tennyson *def of Chemistry Some ruthenium–hydride complexes react with O2 to yield H2O2, therefore the principle of microscopic À reversibility dictates that the reverse reaction is also possible, that H2O2 could transfer an H to a Ru complex. Mechanistic evidence is presented, using the Ru-catalyzed ABTScÀ reduction reaction as a probe, which suggests that a Ru–H intermediate is formed via deinsertion of O2 from H2O2 following Received 5th December 2018 À coordination to Ru. This demonstration that H O can function as an H donor and reductant under Accepted 7th December 2018 2 2 biologically-relevant conditions provides the proof-of-concept that H2O2 may function as a reductant in DOI: 10.1039/c8sc05418e living systems, ranging from metalloenzyme-catalyzed reactions to cellular redox homeostasis, and that À rsc.li/chemical-science H2O2 may be viable as an environmentally-friendly reductant and H source in green catalysis. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported Licence. Introduction bond and be subsequently released as H2O2 (Scheme 1A, red arrows).12,13 The principle of microscopic reversibility14 there- Hydrogen peroxide and its descendant reactive oxygen species fore dictates that it is mechanistically equivalent for H2O2 to (ROS) have historically been viewed in biological systems nearly react with a Ru complex and be subsequently released as O2 exclusively as oxidants that damage essential biomolecules,1–3 with concomitant formation of a Ru–H intermediate (Scheme but recent reports have shown that H2O2 can also perform 1A, blue arrows). -

Organometallics Study Meeting H.Mitsunuma 1

04/21/2011 Organometallics Study Meeting H.Mitsunuma 1. Crystal field theory (CFT) and ligand field theory (LFT) CFT: interaction between positively charged metal cation and negative charge on the non-bonding electrons of the ligand LFT: molecular orbital theory (back donation...etc) Octahedral (figure 9-1a) d-electrons closer to the ligands will have a higher energy than those further away which results in the d-orbitals splitting in energy. ligand field splitting parameter ( 0): energy between eg orbital and t2g orbital 1) high oxidation state 2) 3d<4d<5d 3) spectrochemical series I-< Br-< S2-< SCN-< Cl-< N -,F-< (H N) CO, OH-< ox, O2-< H O< NCS- <C H N, NH < H NCH CH NH < bpy, phen< NO - - - - 3 2 2 2 5 5 3 2 2 2 2 2 < CH3 ,C6H5 < CN <CO cf) pairing energy: energy cost of placing an electron into an already singly occupied orbital Low spin: If 0 is large, then the lower energy orbitals(t2g) are completely filled before population of the higher orbitals(eg) High spin: If 0 is small enough then it is easier to put electrons into the higher energy orbitals than it is to put two into the same low-energy orbital, because of the repulsion resulting from matching two electrons in the same orbital 3 n ex) (t2g) (eg) (n= 1,2) Tetrahedral (figure 9-1b), Square planar (figure 9-1c) LFT (figure 9-3, 9-4) - - Cl , Br : lower 0 (figure 9-4 a) CO: higher 0 (figure 9-4 b) 2. Ligand metal complex hapticity formal chargeelectron donation metal complex hapticity formal chargeelectron donation MR alkyl 1 -1 2 6-arene 6 0 6 MH hydride 1 -1 2 M MX H 1 -1 2 halogen 1 -1 2 M M -hydride M OR alkoxide 1 -1 2 X 1 -1 4 M M -halogen O R acyl 1 -1 2 O 1 -1 4 M R M M -alkoxide O 1-alkenyl 1 -1 2 C -carbonyl 1 0 2 M M M R2 C -alkylidene 1 -2 4 1-allyl 1 -1 2 M M M O C 3-carbonyl 1 0 2 M R acetylide 1 -1 2 MMM R R C 3-alkylidine 1 -3 6 M carbene 1 0 2 MMM R R M carbene 1 -2 4 R M carbyne 1 -3 6 M CO carbonyl 1 0 2 M 2-alkene 2 0 2 M 2-alkyne 2 0 2 M 3-allyl 3 -1 4 M 4-diene 4 0 4 5 -cyclo 5 -1 6 M pentadienyl 1 3. -

Agostic Interaction and Intramolecular Proton Transfer from the Protonation

Agostic interaction and intramolecular proton SPECIAL FEATURE transfer from the protonation of dihydrogen ortho metalated ruthenium complexes Andrew Toner†, Jochen Matthes†‡, Stephan Gru¨ ndemann‡, Hans-Heinrich Limbach‡, Bruno Chaudret†, Eric Clot§, and Sylviane Sabo-Etienne†¶ †Laboratoire de Chimie de Coordination du Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, Associe´a` l’Universite´Paul Sabatier, 205 route de Narbonne, 31077 Toulouse Cedex 04, France; ‡Institute of Chemistry, Freie Universita¨t Berlin, Takustrasse 3, D-14195 Berlin, Germany; and §Laboratoire de Structure et Dynamique des Syste`mes Mole´culaires et Solides (Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, Unite´Mixte de Recherche 5253), Institut Charles Gerhardt, case courrier 14, Universite´Montpellier II, Place Euge`ne Bataillon, 34000 Montpellier, France Edited by Jay A. Labinger, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA, and accepted by the Editorial Board January 17, 2007 (received for review October 13, 2006) Protonation of the ortho-metalated ruthenium complexes insertion of an olefin into the aromatic C–H bond ortho to an i phenylpyridine (ph-py) (1), benzoquinoline activating ketone group (Eq. 1) (30). In this system, the key-2 ؍ RuH(H2)(X)(P Pr3)2 [X i ؉ ؊ bq) (2)] and RuH(CO)(ph-py)(P Pr3)2 (3) with [H(OEt2)2] [BAr4] intermediate is an ortho-metalated complex resulting from ortho) CF3)2C6H3)4B]) under H2 atmosphere yields the corre- C–H bond activation, thanks to chelating assistance with the donor)-3,5)] ؍ BAr4) sponding cationic hydrido dihydrogen ruthenium complexes group. Coordination of the olefin, olefin insertion into Ru–H and i phenylpyridine (ph-py) (1-H); ben- C–C coupling are the subsequent steps needed to close the catalytic ؍RuH(H2)(H-X)(P Pr3)2][BAr4][X] zoquinoline (bq) (2-H)] and the carbonyl complex [RuH(CO)(H-ph- cycle as proposed by Kakiuchi and Murai (8). -

20 Catalysis and Organometallic Chemistry of Monometallic Species

20 Catalysis and organometallic chemistry of monometallic species Richard E. Douthwaite Department of Chemistry, University of York, Heslington, York, UK YO10 5DD Organometallic chemistry reported in 2003 again demonstrated the breadth of interest and application of this core chemical field. Significant discoveries and developments were reported particularly in the application and understanding of organometallic compounds in catalysis. Highlights include the continued develop- ment of catalytic reactions incorporating C–H activation processes, the demonstra- 1 tion of inverted electronic dependence in ligand substitution of palladium(0), and the synthesis of the first early-transition metal perfluoroalkyl complexes.2 1 Introduction A number of relevant reviews and collections of research papers spanning the transition metal series were published in 2003. The 50th anniversary of Ziegler catalysis was commemorated3,4 and a survey of metal mediated polymerisation using non-metallocene catalysts surveyed.5 Journal issues dedicated to selected topics included metal–carbon multiple bonds and related organometallics,6 developments in the reactivity of metal allyl and alkyl complexes,7 metal alkynyls,8 and carbon rich organometallic compounds including 1.9 Reviews of catalytic reactions using well-defined precatalyst complexes include alkene ring-closing and opening methathesis using molybdenum and tungsten imido DOI: 10.1039/b311797a Annu. Rep. Prog. Chem., Sect. A, 2004, 100, 385–406 385 alkylidene precatalysts,10 chiral organometallic half-sandwich -

Characterization of Agostic Interactions in Theory and Computation

Characterization of agostic interactions in theory and computation Matthias Lein Centre for Theoretical Chemistry and Physics, New Zealand Institute for Advanced Study, Massey University Auckland Abstract Agostic interactions are covalent intramolecular interactions between an electron deficient metal and a σ-bond in close geometrical proximity to the metal atom. While the classic cases involve CH σ-bonds close to early transition metals like ti- tanium, many more agostic systems have been proposed which contain CH, SiH, BH, CC and SiC σ-bonds coordinated to a wide range of metal atoms. Recent computational studies of a multitude of agostic interactions are reviewed in this contribution. It is highlighted how several difficulties with the theoretical descrip- tion of the phenomenon arise because of the relative weakness of this interaction. The methodology used to compute and interpret agostic interactions is presented and different approaches such as atoms in molecules (AIM), natural bonding orbitals (NBO) or the electron localization function (ELF) are compared and put into con- text. A brief overview of the history and terminology of agostic interactions is given in the introduction and fundamental differences between α, β and other agostic interactions are explained. Key words: agostic interactions, chemical bond, density functional method, ab-initio calculations, computational chemistry, natural bond orbitals, atoms in molecules, electron localization function Contents 1 Introduction 2 arXiv:0807.1751v1 [physics.chem-ph] 10 Jul 2008 1.1 Agostic Interactions by type 3 2 Agostic Interactions by method 6 2.1 Computational Approach 7 2.2 Spectroscopic Approach 16 3 Conclusions 18 4 Acknowledgments 19 References 19 Preprint submitted to Elsevier 22 October 2018 1 Introduction Transition metal compounds which exhibit a close proximity of CH systems to the metal atom were discovered relatively early in the mid 1960’s and early 1970’s as the quality and availability of x-ray crystallography improved [1,2,3,4,5,6]. -

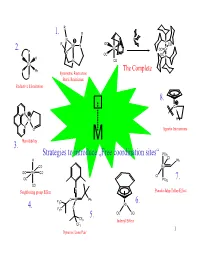

Strategies to Introduce „Free Coordination Sites“ 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8

R 1. R N P R OC P Mo N CO 2. Cr OC Cr P N OC OC P H P N CO Ru TheSteric Complete Restriction P Ph Symmetric Restriction P Steric Restriction Reductive Elimination 8. Co N Pd H N O Agostic Interactions Hemilability M 3. Strategies to introduce „Free coordination sites“ PCy3 Cl H Ph CO Ru OC Mn CO Cl OC PCy3 7. CO Neighboring group Effect N Pseudo-Jahn-Teller-Effect O W Ph F C 3 Rh 6. 4. O F3C 5. OC CO CF3 Indenyl Effect CF3 1 Dynamic Lone Pair 1. Steric restrictions + - N2 + 6 H + 6e R R R R R R R R cat. N N N R R R R N 2 NH3 N N Mo N Mo N + - N N H , e N N R R + - R R -NH3 H , e NH R R R R R R N N Mo N R N R N + - H2N H , e N Mo N N N R R R R R R R R R R R R + - NH2 H , e R R R R H+, e- R + - N R N H , e HN N N Mo N N Mo N -NH3 Mo N N N N N N N 2 Symmetric restrictions R R 1. R R + - N N2 + 6 H + 6e N R cat. R N Mo N 2 NH3 N N 15e-complex rather than 17e-complex E one lone pair is non-bonding! 3 Electron-transfer-Catalysis 1. Electronic restrictions CH3 CH3 PPh 18e-Complex 3 18e-Complex Mn Mn CO CO H CCN slow Ph P 3 CO 3 CO o E =0.19V Eo=0.52V CH3 CH3 PPh 3 17e-Complex 17e-Complex Mn fast Mn CO CO H CCN Ph P 3 CO 3 CO CH3 Mn CO H3CCN CO The reaction works catalytically, because PPh 3 is a stronger π-acid than CH 3CN. -

Symmetry 2010, 2, 1745-1762; Doi:10.3390/Sym2041745 OPEN ACCESS Symmetry ISSN 2073-8994

Symmetry 2010, 2, 1745-1762; doi:10.3390/sym2041745 OPEN ACCESS symmetry ISSN 2073-8994 www.mdpi.com/journal/symmetry Review n– Polyanionic Hexagons: X6 (X = Si, Ge) Masae Takahashi Institute for Materials Research, Tohoku University, 2-1-1 Katahira, Aoba-ku, Sendai 980-8577, Japan; E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel.: +81-22-795-4271; Fax: +81-22-795-7810 Received: 16 August 2010; in revised form: 7 September 2010 / Accepted: 27 September 2010 / Published: 30 September 2010 Abstract: The paper reviews the polyanionic hexagons of silicon and germanium, focusing on aromaticity. The chair-like structures of hexasila- and hexagermabenzene are similar to a nonaromatic cyclohexane (CH2)6 and dissimilar to aromatic D6h-symmetric benzene (CH)6, although silicon and germanium are in the same group of the periodic table as carbon. Recently, six-membered silicon and germanium rings with extra electrons instead of conventional substituents, such as alkyl, aryl, etc., were calculated by us to have D6h symmetry and to be aromatic. We summarize here our main findings and the background needed to reach them, and propose a synthetically accessible molecule. Keywords: aromaticity; density-functional-theory calculations; Wade’s rule; Zintl phases; silicon clusters; germanium clusters 1. Introduction This review treats the subject of hexagonal silicon and germanium clusters, paying attention to the two-dimensional aromaticity. The concept of aromaticity is one of the most fascinating problems in chemistry [1,2]. Benzene is the archetypical aromatic hexagon of carbon: it is a planar, cyclic, fully conjugated system that possesses delocalized electrons. The two-dimensional aromaticity of planar monocyclic systems is governed by Hückel’s 4N + 2 rule, where N is the number of electrons.