Non-Passerines

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

333-03-2013 Parasitic Jaeger

PORC # 333-03-2013 PARASITIC JAEGER Stercocarius parasiticus Observer: Jerry McWilliams Location: Sunset Point, Presque Isle S.P., Erie, Pa. Date: November 19, 2013 Time: 8:08 AM Weather: Cloudy, wind NW to 25 mph, temp. 35 F Viewing distance: about 1/2 mile from shore Optics: Swarovski 8 X 42 Binocular and Kowa TSN 884 Prominar spotting scope from 30X to 60X Details: While conducting the waterbird count from a high hard pan sand dune just east of Sunset Point I spotted an immature light morph jaeger flying low and moving to the west. The rapid wing beats, alternate glides, and size were reminiscent of a Peregrine Falcon, except that the wings were strongly bowed down when gliding. The jaeger was all dark above, very blackish looking, with a bit of white showing at the base of the primaries. The underwings were barred showing just a single white patch at the base of the primaries. The belly was heavily barred on a background of pale rusty brown. I could not see any tail projections. The bird moved up and down above the surface of the water, but often dipped low disappearing inside the troughs between waves as it twisted and turned against the wind . There were no gulls nearby to pursue, so the jaeger continued west pass Sunset Point without any interruptions. The wings were rather narrow and not broad as in Pomarine Jaeger. The ID was based primarily on flight behavior, shape, and size of the bird. Pomarine Jaeger is more robust with broad based wings with a relatively short broad outer arm or hand. -

Tube-Nosed Seabirds) Unique Characteristics

PELAGIC SEABIRDS OF THE CALIFORNIA CURRENT SYSTEM & CORDELL BANK NATIONAL MARINE SANCTUARY Written by Carol A. Keiper August, 2008 Cordell Bank National Marine Sanctuary protects an area of 529 square miles in one of the most productive offshore regions in North America. The sanctuary is located approximately 43 nautical miles northwest of the Golden Gate Bridge, and San Francisco California. The prominent feature of the Sanctuary is a submerged granite bank 4.5 miles wide and 9.5 miles long, which lay submerged 115 feet below the ocean’s surface. This unique undersea topography, in combination with the nutrient-rich ocean conditions created by the physical process of upwelling, produces a lush feeding ground. for countless invertebrates, fishes (over 180 species), marine mammals (over 25 species), and seabirds (over 60 species). The undersea oasis of the Cordell Bank and surrounding waters teems with life and provides food for hundreds of thousands of seabirds that travel from the Farallon Islands and the Point Reyes peninsula or have migrated thousands of miles from Alaska, Hawaii, Australia, New Zealand, and South America. Cordell Bank is also known as the albatross capital of the Northern Hemisphere because numerous species visit these waters. The US National Marine Sanctuaries are administered and managed by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) who work with the public and other partners to balance human use and enjoyment with long-term conservation. There are four major orders of seabirds: 1) Sphenisciformes – penguins 2) *Procellariformes – albatross, fulmars, shearwaters, petrels 3) Pelecaniformes – pelicans, boobies, cormorants, frigate birds 4) *Charadriiformes - Gulls, Terns, & Alcids *Orders presented in this seminar In general, seabirds have life histories characterized by low productivity, delayed maturity, and relatively high adult survival. -

Captive Breeding and Reintroduction of Black Francolin, Grey Francolin and Chukar Partridge (2015-2020) in District Dir Lower, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan

CAPTIVE BREEDING AND REINTRODUCTION OF BLACK FRANCOLIN, GREY FRANCOLIN AND CHUKAR PARTRIDGE (2015-2020) IN DISTRICT DIR LOWER, KHYBER PAKHTUNKHWA, PAKISTAN Syed Fazal Baqi Kakakhel Naveed Ul Haq Ejaz Ul Haq European Journal of Biology Vol.5, Issue 2, pp 1-9, 2020 CAPTIVE BREEDING AND REINTRODUCTION OF BLACK FRANCOLIN, GREY FRANCOLIN AND CHUKAR PARTRIDGE (2015-2020) IN DISTRICT DIR LOWER, KHYBER PAKHTUNKHWA, PAKISTAN Syed Fazal Baqi Kakakhel¹*, Naveed Ul Haq², Ejaz Ul Haq³ ¹Conservator Wildlife Northern Circle Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Wildlife Department, Pakistan ²Deputy Conservator Wildlife Dir Wildlife Division Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Wildlife Department, Pakistan ³Sub Divisional Wildlife officer Dir Lower Wildlife Sub Division, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Wildlife Department Pakistan *Crresponding Author’s E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT Purpose: The ex-situ conservation aims to discover new populations or supports the populations that yet survive in the wild. To breed animals in captivity and release them in their natural control habitats is one of the conservation methods. Amongst other species partridges also breed in captivity and can be release in the wild but presently data lacking, need to examine. Chukar partridge, Black francolin and Grey francolin are used for sports hunting in Pakistan. The available record on captive breeding of Chukar partridge, Black francolin and Grey francilin and their release in the wild for the years 2015-2020 was reviewed using a developed questionnaire. Methodology: Review record of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Wildlife Department Pakistan through a developed questionnaire Findings: It was found that the maximum number of chukar partridge breed was 36, Black francolin (6) and Grey francolin (24). Out of the breeding stock, Chukar partridges (44) and Grey francolin (28) were released in the wild to its natural habitat by hard release technique. -

Population Biology of Black Francolin (Francolinus Francolinus) with Reference to Lal Suhanra National Park, Pakistan*

Pakistan J. Zool., vol. 45(1), pp. 183-191, 2013. Population Biology of Black Francolin (Francolinus francolinus) with Reference to Lal Suhanra National Park, Pakistan* Waseem Ahmad Khan1 and Afsar Mian2 1Animal Ecology Laboratory, Islamabad Model Postgraduate College, H-8, Islamabad 2Bioresource Research Centre, 34, Bazaar Road, G-6/4, Islamabad, Pakistan Abstract.- Transect data collected on black francolin, known as black partridge in Pakistan and India, (Francolinus francolinus) population from Lal Suhanra National Park (south Punjab, Pakistan) between 1993 and 2004 suggested that the species was present in only 6/23 stands (mainly in irrigated plantation with reed vegetation) with an average density of 8.40±1.39/km²; varying between 3.44±0.88 and 13.28±2.25/km2 in different stands. Densities were lower during winter (November–March, minimum in February) and maximum during summer (May- July), explained on population recruitment cycle, mortality and local movements. Densities were not significantly different between study years, yet these were generally lower during drought years compared to better rainfall years. Sex ratio (male/ female = 1.31) was skewed towards males. There were 0.32±0.09 young/adult female and 0.14±0.03 young/adult birds, while 2/6 stands had no young, representing non-breeding stands. Young were not observed or could not be identified separately during October-February, and the young/adult ratio was the highest in August. Dispersion index (variance/mean) of 0.60±0.09 suggests random-uniform dispersion. Group size averaged at 1.88±0.15 birds/group (range 1-5), majority of individuals appeared as singles (52.39%). -

Gear for a Big Year

APPENDIX 1 GEAR FOR A BIG YEAR 40-liter REI Vagabond Tour 40 Two passports Travel Pack Wallet Tumi luggage tag Two notebooks Leica 10x42 Ultravid HD-Plus Two Sharpie pens binoculars Oakley sunglasses Leica 65 mm Televid spotting scope with tripod Fossil watch Leica V-Lux camera Asics GEL-Enduro 7 trail running shoes GoPro Hero3 video camera with selfie stick Four Mountain Hardwear Wicked Lite short-sleeved T-shirts 11” MacBook Air laptop Columbia Sportswear rain shell iPhone 6 (and iPhone 4) with an international phone plan Marmot down jacket iPod nano and headphones Two pairs of ExOfficio field pants SureFire Fury LED flashlight Three pairs of ExOfficio Give- with rechargeable batteries N-Go boxer underwear Green laser pointer Two long-sleeved ExOfficio BugsAway insect-repelling Yalumi LED headlamp shirts with sun protection Sea to Summit silk sleeping bag Two pairs of SmartWool socks liner Two pairs of cotton Balega socks Set of adapter plugs for the world Birding Without Borders_F.indd 264 7/14/17 10:49 AM Gear for a Big Year • 265 Wildy Adventure anti-leech Antimalarial pills socks First-aid kit Two bandanas Assorted toiletries (comb, Plain black baseball cap lip balm, eye drops, toenail clippers, tweezers, toothbrush, REI Campware spoon toothpaste, floss, aspirin, Israeli water-purification tablets Imodium, sunscreen) Birding Without Borders_F.indd 265 7/14/17 10:49 AM APPENDIX 2 BIG YEAR SNAPSHOT New Unique per per % % Country Days Total New Unique Day Day New Unique Antarctica / Falklands 8 54 54 30 7 4 100% 56% Argentina 12 435 -

Recognizable Forms

123 Recognizable Forms Morphs of the Parasitic Jaeger by Ron Pittaway and Peter Burke Introduction Goodwin (1995). and there is an Parasitic Jaegers (Stercorarius excellent site guide to seeing jaegers parasiticus) are seagoing pirates at Sarnia in OFO NEWS (Rupert during the nonbreeding season, 1995). Parasitic Jaegers are casual in making their living by robbing gulls, spring in southern Ontario. terns and other seabirds by forcing Adult Parasitic Jaegers are them to disgorge or drop their prey. variable in appearance, but generally Seeing a Parasitic Jaeger accelerating occur in three colour morphs Peregrine-like, swiftly pursuing a tern (phases): light, intermediate and until it drops its fish, then catching dark. See Figure 1. Our classification the fish in mid-air before it strikes of adult morphs is based on the the water, is an unforgettable sight. descriptions in the genetic studies of On their tundra breeding grounds, O'Donald (1983) and O'Donald in they also prey on small birds, eggs Cooke and Buckley (1987). Juvenile and young birds, lemmings, and morphs are also variable in invertebrates such as insects and appearance; see the light, spiders. Skuas and jaegers, subfamily intermediate and dark morph Stercorariinae, are unique among juveniles illustrated in Figure 2. birds in having the combination of In this article, we discuss the strong, sharply hooked claws and distinguishing features, frequency fully webbed feet. and distribution, and genetics of the In Canada, the Parasitic Jaeger three morphs of the Parasitic Jaeger breeds in the Arctic south to northern in Ontario. Discussion is restricted to Ontario (Godfrey 1986). It is a "rare adults in breeding plumage and summer resident along the Hudson juveniles because these are the two Bay coast" of Ontario (James 1991). -

Genetic Structure and Diversity of Black Francolin in Uttarakhand, Western Himalaya, India

Journal of Wildlife and Biodiversity 4(1): 29-39 (2020) -(http://jwb.araku.ac.ir/) Research Article DOI: 10.22120/jwb.2019.115300.1093 Genetic structure and diversity of Black Francolin in Uttarakhand, Western Himalaya, India populations (2.99%). Overall the populations of 1* 2 Priyanka Negi , Atul Kathait , Tripti black francolin were genetically variable with Negi3, Pramesh Lakhera1 high adaptive potential in Uttarakhand, Western 1* Himalaya. Department of Zoology, Eternal University Baru sahib, India Keywords: Conservation, heterozygosity, 2 School of Life Science, ApeejaySatya University, homozygosity, genetic diversity, microsatellite Gurgaon, India markers, polymorphic sites 3School of Environment and Natural Resources, Doon University, Dehradun, India Introduction *email: [email protected] The increased pressure of habitat fragmentation, Received: 04 October 2019 / Revised: 12 November 2019 / Accepted: 02 November 2019 / Published online: 05 January overhunting and induced anthropogenic activity, 2020. Ministry of Sciences, Research and Technology, Arak put the number of species in threat. The University, Iran. Himalayan geographical region is facing the Abstract same. The protection of species requires a The present study evaluates the genetic diversity thorough understanding of species biology as well as of the level and distribution of genetic of black francolin (Francolinus francolinus diversity (Neel andEllstrand 2003). The latter is asiae) in Uttarakhand on the basis of an important factor for the adaptation and microsatellite -

Habitat Preference of the Sole Wild Population of Francolinus Bicalcaratus Ayesha in the Palearctic: Implications for Conservation and Management

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by I-Revues Revue d’Ecologie (Terre et Vie), Vol. 71 (3), 2016 : 288-297 HABITAT PREFERENCE OF THE SOLE WILD POPULATION OF FRANCOLINUS BICALCARATUS AYESHA IN THE PALEARCTIC: IMPLICATIONS FOR CONSERVATION AND MANAGEMENT 1* 2 1 3 Saâd HANANE , Nabil ALAHYANE , Najib MAGRI , Mohamed-Aziz EL AGBANI 3 & Abdeljebbar QNINBA 1 Forest Research Center, High Commission for Water, Forests and Desertification Control, Avenue Omar Ibn El Khattab, BP 763, 10050, Rabat-Agdal, Morocco. 2 Faculté des Sciences de Rabat, 4 Avenue Ibn Battouta, BP 1014 RP, 10090, Agdal-Rabat, Morocco. 3 Université Mohammed V-Agdal, Institut Scientifique de Rabat, Avenue Ibn Battouta, BP 703, 10090, Agdal-Rabat, Morocco. * Corresponding author. E-mail : [email protected] ; phone: +212 660 125799 ; Fax: +212 537 671151 RÉSUMÉ.— Préférence d’habitat de la seule population sauvage de Francolinus bicalcaratus ayesha dans le Paléarctique : implications pour sa conservation et sa gestion.— Le Francolin à double éperon (Francolinus bicalcaratum ayesha) est un oiseau en danger critique d’extinction et endémique du Maroc, où il habite les forêts de chêne-liège. Ses populations ont été réduites principalement en raison de la chasse et de la destruction des habitats. La caractérisation de l’habitat utilisé par ces oiseaux indigènes peut optimiser les programmes futurs de réintroduction. La méthode de détection auditive a été utilisée sur des transects pour localiser les mâles chanteurs. Nous avons analysé les facteurs qui déterminent la présence du Francolin à double éperon dans le Nord-Ouest du Maroc en considérant 13 variables explicatives. -

Parasitic Jaeger)

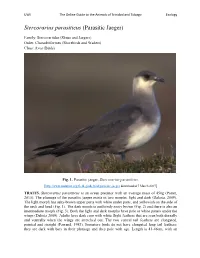

UWI The Online Guide to the Animals of Trinidad and Tobago Ecology Stercorarius parasiticus (Parasitic Jaeger) Family: Stercorariidae (Skuas and Jaegers) Order: Charadriiformes (Shorebirds and Waders) Class: Aves (Birds) . Fig. 1. Parasitic jaeger, Stercorarius parasiticus. [http://www.audubon.org/field-guide/bird/parasitic-jaeger downloaded 7 March 2017] TRAITS. Stercorarius parasiticus is an ocean predator with an average mass of 450g (Potter, 2015). The plumage of the parasitic jaeger exists in two morphs, light and dark (Dakota, 2009). The light morph has ashy-brown upper parts with white under parts, and yellowish on the side of the neck and head (Fig. 1). The dark morph is uniformly sooty brown (Fig. 2) and there is also an intermediate morph (Fig. 3). Both the light and dark morphs have pale or white panels under the wings (Dakota 2009). Adults have dark caps with white flight feathers that are seen both dorsally and ventrally when the wings are stretched out. The two central tail feathers are elongated, pointed and straight (Farrand, 1983). Immature birds do not have elongated long tail feathers; they are dark with bars in their plumage and they pale with age. Length is 41-46cm, with an UWI The Online Guide to the Animals of Trinidad and Tobago Ecology average wing span of 118cm. The parasitic jaeger has a slightly hooked beak which is greyish- black, as well as the legs. Males and females are similar in physical appearance; females tend to be larger than males (Dakota, 2009). DISTRIBUTION. Stercorarius parasiticus breeds in the Arctic in the Northern Hemisphere and migrates to areas of the Southern Hemisphere where they are mostly seen in southern oceans (Wiley and Lee, 1999). -

Sighting of Parasitic Jaeger Stercorarius Parasiticus in Little Rann of Kachchh, Gujarat Prasad Ganpule

72 Indian BirDS Vol. 7 No. 3 (Publ. 21 October 2011) Sighting of Parasitic Jaeger Stercorarius parasiticus in Little Rann Of Kachchh, Gujarat Prasad Ganpule Ganpule, P., 2011. Sighting of Parasitic Jaeger Stercorarius parasiticus in Little Rann of Kachchh, Gujarat. Indian BIRDS 7 (3): 72. Prasad Ganpule, C/o Parshuram Pottery Works, Opp. Nazarbaug Station, Morbi 363642, Gujarat, India. Email: [email protected] n 27 September 2009, at 1600 hrs, I went to the western juvenile or a dark-phase bird. most point of the Little Rann Of Kachchh near Venasar The pelagic Parasitic Jaeger is reported from the coast of Ovillage (23°08’N, 70°56’E), which is c. 45 km from Morbi, Pakistan, and off the western coast of Sri Lanka (Kazmierczak Rajkot district, Gujarat. 2000). There are a handful of records from the western coast This is a coastal lagoon with a freshwater lake on one side. of India during winter. It is reported from Colaba Point, Mumbai The area is quite large and is usually flooded till the month of (Sinclair 1977), and from Gokarn, Karnataka (Madsen 1990). February. The only previous record of the Parasitic Jaeger from Gujarat I was observing birds at the coastal lagoon and saw hundreds is of a possible juvenile bird from Diu, which was identified of Black-headed Gulls Larus ridibundus along with good numbers tentatively as this species or a Pomarine Jaeger S. pomarinus of Pallas’s Gulls L. ichthyaetus, Caspian Terns Sterna caspia, etc. (Mundkur et al. 2009). The present record is the first photographic I then observed a large bird in flight, which I could not identify. -

Bird-O-Soar Black Francolin Expanding Its Range Into Thar Desert

#44 Bird-o-soar 21 April 2020 Black Francolin expanding its range into Thar Desert Black Francolin male in the Vallabhgarden area of Bikaner region. © Jitendra Solanki. Black Francolin Francolinus francolinus patches in Sri Ganganagar District. The (Linnaeus, 1766), a resident species in its species occurs here, maybe, due to alteration range, is well distributed from southern of habitat as irrigation has been in practice Afghanistan through Indus Valley of Pakistan, since 1960 in this area (Singh et al. 2009). Kachchh in Gujarat, along the Himalaya Roberts (1991) reported that the species had to Assam, to Bangladesh, to Odisha and declined rapidly during early 90s in Pakistan central India (Rasmussen & Anderton 2012). in most of its distribution range and is entirely Though the species is assessed as Least absent from the main desert tracks of Thar or Concern as per IUCN Red List, its population Cholistan. is declining in many parts of its distribution range (Birdlife International 2018). Grimmet Though Black Francolin has been frequently et al. (1998) and Kazmierczak & Perlo (2000) reported from Tal Chhapar Blackbuck report that the species is almost absent from Sanctuary, which is largely a flat tract of the Indian part of Thar Desert except small grassland present in Churu District, it is Zoo’s Print Vol. 35 | No. 4 21 #44 Bird-o-soar 21 April 2020 report of the species from the core area of Thar Desert. We had earlier sighted this species in Jhunjhnu and Churu districts of Rajasthan and Suratgarh Tehsil of Sri Ganganagar District. The avian diversity of Thar Desert is changing considerably due to Indira Gandhi Canal and several species appear to be invading the core region of Thar Desert because of these ecological changes (Patil et al. -

A Checklist of Birds of Britain (9Th Edition)

Ibis (2018), 160, 190–240 doi: 10.1111/ibi.12536 The British List: A Checklist of Birds of Britain (9th edition) CHRISTOPHER J. MCINERNY,1,2 ANDREW J. MUSGROVE,1,3 ANDREW STODDART,1 ANDREW H. J. HARROP1 † STEVE P. DUDLEY1,* & THE BRITISH ORNITHOLOGISTS’ UNION RECORDS COMMITTEE (BOURC) 1British Ornithologists’ Union, PO Box 417, Peterborough PE7 3FX, UK 2School of Life Sciences, University of Glasgow, Glasgow G12 8QQ, UK 3British Trust for Ornithology, The Nunnery, Thetford, IP24 2PU, UK Recommended citation: British Ornithologists’ Union (BOU). 2018. The British List: a Checklist of Birds of Britain (9th edition). Ibis 160: 190–240. and the Irish Rare Birds Committee are no longer INTRODUCTION published within BOURC reports. This, the 9th edition of the Checklist of the Birds The British List is under continuous revision by of Britain, referred to throughout as the British BOURC. New species and subspecies are either List, has been prepared as a statement of the status added or removed, following assessment; these are of those species and subspecies known to have updated on the BOU website (https://www.bou. occurred in Britain and its coastal waters (Fig. 1). org.uk/british-list/recent-announcements/) at the time It incorporates all the changes to the British List of the change, but only come into effect on the List up to and including the 48th Report of the British on publication in a BOURC report in Ibis. A list of Ornithologists’ Union Records Committee the species and subspecies removed from the British (BOURC) (BOU 2018), and detailed in BOURC List since the 8th edition is shown in Appendix 1.