01 Diss Cover Page

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2018 / 2019 Plan Des Lignes Interurbaines

11 ANNEMASSE - SAINT-JULIEN-EN-GENEVOIS SAT THONON 13 FRANGY - SAINT-JULIEN-EN-GENEVOIS SAT THONON n 21 ANNECY - SEYSSEL BUSTOURS / VOYAGES GRILLET / TRANSPORTS AIN a 22 ANNECY - BELLEGARDE BUSTOURS / VOYAGES GRILLET / TRANSPORTS AIN m 51 ANNECY - ALBERTVILLE PHILIBERT / LOYET / FRANCONY EVIAN- 52 ANNECY - DUINGT PHILIBERT / LOYET / FRANCONY é LES-BAINS tin 61 ANNECY - TALLOIRES-MONTMIN TRANSDEV HAUTE-SAVOIE e e L Pont RougeChamp Poirier 131 62 ANNECY - MASSIF DES ARAVIS TRANSDEV HAUTE-SAVOIE 141 ÉVIAN-LES-BAINS Hôpital etite Riv Port Maourronder Locum Bleu LémanandeRond Riv PointP du Gallia T Ancienne Gare 63 ANNECY - DINGY-SAINT-CLAIR - THÔNES TRANSDEV HAUTE-SAVOIE Gr LUGRIN Chef Lieu Bret T71 ÉVIAN-LES-BAINS Gare routière EmbarcadèreHôpitalVVF MEILLERIE MAXILLY 131 Plage 81 CHAMONIX-MONT-BLANC - CLUSES SAT PASSY AMPHION Les Aires D1005 131 SAINT-GINGOLPH Route Nationale Amphion Stade Le Nouy 82 CHAMONIX-MONT-BLANC - PRAZ-SUR-ARLY SAT PASSY c La Rive Moulin à Poivre Maraiche Carrefour Cité de l’Eau Vuarche 124 83 SALLANCHES - PRAZ-SUR-ARLY SAT PASSY Cora Léchère Noailles Verts Pratz Office de Tourisme SAINT-GINGOLPH a Vongy Eglise Meserier Thony Rond- Verlagny Chef Lieu 84 SALLANCHES - LES CONTAMINES-MONTJOIE SAT PASSY Senaillet Point Milly Le Clou 122 THOLLON-LES-MÉMISES 85 SALLANCHES - PASSY SAT PASSY Morand 123 Poese Chef Lieu D24 Chez Vesin THOLLON-LES-MÉMISES L 122 Carrefour 122 Chez Cachat La Joux Pont de PUBLIER Roseires 86 SALLANCHES - CORDON SAT PASSY Dranse Église L'X Forchex Chez Bruchon Chez les Praubert 91 CLUSES - MORZINE -

Les Alpes-Maritimes En 600 Questions Jeu

ARCHIVES DÉPARTEMENTALES Les Alpes-Maritimes en 600 questions • Personnalités • Géographie • Histoire • XXe siècle • Art • Cuisine, spécialités & traditions Jeu S’adapte à la plupart des plateaux de jeux de questions culturelles (version à imprimer sur fiches bristol 10,5 x 14,8 cm) --- Jean-Bernard LACROIX, les Alpes-Maritimes en 600 questions 1996. • Quel président du conseil français (= premier ministre) est enterré à Nice ? Léon Gambetta, fils d'un épicier niçois, a été inhumé au cimetière du Château à Nice en 1883 à l'issue d'obsèques solennelles. • Quel est le point culminant des Alpes-Maritimes ? La cime de Gelas s'élève à 3143 mètres à la frontière italienne. Elle fut escaladée pour la première fois en 1864. • Qu'à-t-on trouvé dans la grotte du Vallonet à Roquebrune-Cap-Martin ? La grotte du Vallonet a révélé les traces d'un des plus anciens habitats connus en Europe vieux d'environ 900.000 ans. • Quelles sont les deux dernières communes devenues françaises ? En 1947, le traité de Paris a donné à la France Tende et La Brigue dans la haute vallée de la Roya. • A quel artiste doit-on la statue représentant l'Action enchaînée à Puget-Théniers ? Aristide Maillol a réalisé cette œuvre en 1908 en hommage au théoricien socialiste Louis Auguste Blanqui. • En quoi consiste la socca ? Mets traditionnel niçois, la socca est une semoule de pois chiche gratinée qui donnait lieu autrefois à un commerce ambulant. Dernière rectification de frontière Les combats de l'Authion dans lesquels le général de Gaulle a engagé la 1ère Division Française Libre en avril 1945 ont permis la libération des Alpes-Maritimes et le rattachement de Tende et La Brigue restés italiens lors de l'annexion du Comté de Nice en 1860. -

Plan Local D'urbanisme Intercommunal : Dessinons Ensemble Le Bas-Chablais De Demain

N°18 OCTOBRE 2016 Anthy-sur-Léman Ballaison Bons-en-Chablais Brenthonne Chens-sur-Léman Douvaine Excenevex Fessy Loisin Lully Margencel Massongy Messery Nernier Sciez Veigy-Foncenex Yvoire Regards croisés sur l’actualité de la Communauté de Communes du Bas-Chablais Plan local d'urbanisme intercommunal : dessinons ensemble le Bas-Chablais de demain se ressourcer vivre innover travailler DOSSIER URBANISME P. 6 > 9 TOURISME EVIAN Publier Un patrimoine et des LAC LÉMAN Marin Champanges Thonon- activités à valoriser les-Bains Yvoire Nernier Anthy-sur- Armoy Féternes Léman p. 13 Messery Excenevex Margencel Allinges Lyaud Reyvroz Massongy Chens- Sciez sur-Léman Orcier Douvaine Perrignier Draillant Vailly Ballaison Lully Cervens DÉPLACEMENTS INSTITUTIONS Lullin Loisin Veigy-Foncenex Fessy Sciez et Douvaine : La Communauté Bons-en-Chablais Brenthonne Habère- Poche Bellevaux Machilly la recherche de d'Agglomération Saxel Burdignin Habère- er Saint- Lullin solutions globales créée le 1 janvier 2017 Cergues Boëge p. 11 p. 14GENÈVE ANNEMASSE Communauté d’agglomération www.cc-baschablais.com arret Retour sur images sur nos temps forts CITOYENNETÉ 25 juin - Le Conseil Municipal des Jeunes de Douvaine est allé à la rencontre des responsables de la communauté de communes au Domaine de Thénières à Ballaison. Un échange a permis aux jeunes, très attentifs, de mieux connaître et comprendre les enjeux et le fonctionnement d’un établissement public de coopération intercommunale. Le rendez-vous s’est terminé par une visite des locaux dans le Château. Une expérience fructueuse que la communauté de communes propose de reconduire avec d’autres conseils des jeunes. GEOPARK 13-15 août - Une délégation UNESCO était en visite dans le Chablais avec pour objectif de confirmer la labellisation du territoire en tant que « Géoparc mondial UNESCO ». -

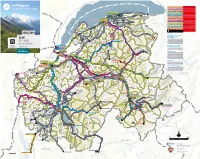

Guide Des Transports Interurbains Et Scolaires De La Haute-Savoie

2018 Guide des Transports interurbains et scolaires Haute-Savoie Guide des transports interurbains et scolaires 2018 - Haute-Savoie Sommaire Les points d’accueil transporteurs Les points d’accueil transporteurs ................ p. 3 TRANSDEV HAUTE-SAVOIE SAT - PASSY • ANNECY • PAE du Mont-Blanc 74190 PASSY Siège social - 10 rue de la Césière Tél : 04 50 78 05 33 Z.I. de Vovray 74600 ANNECY • Gare routière de Megève 74120 MEGÈVE Tél : 04 50 51 08 51 Tél : 04 50 21 25 18 Les points d’accueil transport scolaire .......... p. 4 Gare routière - 74000 ANNECY • Gare routière de Saint-Gervais le Fayet Tél : 04 50 45 73 90 74170 SAINT-GERVAIS-LES-BAINS • THÔNES Tél : 04 50 93 64 55 Gare routière - 2 route du Col des Aravis • Gare routière de Sallanches 74230 THÔNES 74700 SALLANCHES Les localités desservies ................................p. 5-7 Tél : 04 50 02 00 11 Tél : 04 50 58 02 53 • LE GRAND-BORNAND SAT - THONON Gare routière 74450 LE GRAND-BORNAND • Gare routière place des Arts Tél : 04 50 02 20 58 74200 THONON-LES-BAINS La carte des lignes ..................................... p. 8-9 • LA CLUSAZ Tél : 04 50 71 85 55 Gare routière - 39 route des Riondes • AUTOCARS SAT Siège social 74220 LA CLUSAZ 5 rue Champ Dunand Tél : 04 50 02 40 11 74200 THONON-LES-BAINS • THONON-LES-BAINS Tél : 04 50 71 00 88 La carte Déclic’ ............................................. p. 10 Boutique transport place des Arts • Gare routière de Morzine 74110 MORZINE 74200 THONON-LES-BAINS Tél : 04 50 79 15 69 Tél : 04 50 81 74 74 • Bureau SAT Châtel 74390 CHÂTEL • GENÈVE Tél : 04 50 73 24 29 Gare routière place Dorcière GENÈVE (Suisse) sat-autocars.com Tél : 0041 (0)22/732 02 30 Car+bus ticket gagnant ................................ -

Les Maires De Haute-Savoie

Les Maires de Haute-Savoie Collectivité Nom Prénom Adresse1 Adresse2 Code Postal Ville GIRARD- ABONDANCE Paul Mairie Chef-Lieu BP1 74360 ABONDANCE DESPRAULEX Jean- ALBY-SUR-CHERAN MARTIN Mairie 4 Rue Etroite 74540 ALBY-SUR-CHERAN Claude Jean- ALEX DAL GOBBO Mairie Place de l'église 74290 ALEX Claude ALLEVES DELORME Noëlle Mairie Chef Lieu 74540 ALLEVES Jean- ALLINGES FILLION Mairie Chef Lieu 74200 ALLINGES Pierre ALLONZIER-LA- 1 route de Sous le PECCI Gilles Mairie 74350 ALLONZIER-LA-CAILLE CAILLE Mont AMANCY MONET Claude Mairie Chef Lieu 74800 AMANCY AMBILLY MATHELIER Guillaume Mairie B.P. 722 74111 AMBILLY Cedex 36 Chemin du ANDILLY HUMBERT Vincent Mairie 74350 ANDILLY Champ de Foire Hôtel de ANNECY RIGAUT Jean-Luc BP 2305 74011 ANNECY Cedex Ville ANNECY-LE-VIEUX ACCOYER Bernard Mairie Pl G. Fauré - BP 249 74942 ANNECY-LE-VIEUX CEDEX ANNEMASSE DUPESSEY Christian Mairie B.P. 530 74107 ANNEMASSE CEDEX ANTHY-SUR-LEMAN VESIN Jean-Paul Mairie 7 rue de la mairie 74200 ANTHY-SUR-LEMAN ARACHES-LA- ROSA Patricia Mairie 74300 ARACHES FRASSE 83 impasse de ARBUSIGNY DELIEUTRAZ Laurent Mairie 74930 ARBUSIGNY l'Eglise ARCHAMPS JOUVENOZ Bernard Mairie BP40 74165 COLLONGES-SOUS- SALEVE Cedex ARENTHON VELLUZ Alain Mairie 22 Route de Reignier 74800 ARENTHON ARGONAY FRANCOIS Gilles Mairie 1 Place Arthur Lavy 74370 ARGONAY 202 Route Bois de la ARMOY RABHI Laurent Mairie 74200 ARMOY Cour ARTHAZ-PONT- 94 Rte de Pt Nt D. - PELLEVAT Cyril Mairie 74380 ARTHAZ-PONT-NOTRE-DAME NOTRE-DAME BP 1 AVIERNOZ CLERC Claude Mairie 18 route des Glières 74570 AVIERNOZ Jean- -

A Great Season, Everyone!

GUIDE FOR SEASONAL WORKERS WINTER/SUMMER 2010-2011 HAVE A GREAT Pays du Mont-Blanc - Arve Valley SEASON Hello and welcome! 652,000 tourist beds 2nd most popular department for tourism in France From Mont Blanc and the Aravis mountains to the shores of Lake Léman and Lake Annecy, Haute-Savoie offers an idyllic setting for numerous seasonal employees. These workers help ensure enjoyable holidays for tourists from all over the globe. With the current economic climate showing signs of improvement, tourism remains the number one job creation sector in Haute Savoie, showing expansion in the hospitality and ski lift industries. Tourism is an industry that can’t be relocated overseas, and thus represents a vital asset for the future. Since 2007, the public authorities (national government, Regional Councils, and General Councils), elected officials, labour and management groups, and all players involved in social issues (C.A.F., C.P.A.M., M.S.A., subsidized housing, occupational health services) have mobilized to promote seasonal employment as a priority for the department, notably including it in a goals charter. With this framework in mind, and to ensure that seasonal workers « have a good season », the regions of Pays du Mont Blanc and Chablais have mobilized to welcome these employees by means of the Chamonix « Espace Saisonnier » (centre for seasonal workers) and the Chablais « Point Accueil Saisonnier » (information desk for seasonal workers). On a larger scale, Haute-Savoie strives to inform seasonal workers more thoroughly by publishing this guide. Here, employees and employers will find answers to a variety of questions that may concern them, including training, employment, working conditions, health, and housing. -

Arve Faucigny Genevois Albanais Pays Du Rhône » a Été Scindé

Crédit : BlancRibotSavoiephotoMont / ARVE FAUCIGNY GENEVOIS Edition 2021 Dans l’économie touristique de Savoie Mont Blanc, le secteur Arve - Faucigny - Genevois - Albanais - Pays du Rhône, représente : • 4% des lits touristiques • 7% des emplois liés au tourisme • 4% de la fréquentation ski nordique en journées skieurs CAPACITE D’ACCUEIL Source : Observatoire SMBT 2020 nombre de lits CARACTERISTIQUES DU TERRITOIRE • Superficie : 1 316 km² • 130 communes • 337 738 habitants (source : INSEE 2018) • Soit 27% de la population de Savoie Mont Blanc et 41% de la population du département de Haute-Savoie • Taux d’évolution annuel : +2,5% pour la période 1999-2018 Evolution de la population résidente • 58 800 lits touristiques (9 705 structures) • 4% de la capacité d’accueil de Savoie Mont Blanc • 8% de la capacité d’accueil de la Haute-Savoie • 20% sont des lits marchands (12 000 lits) • L’hôtellerie représente 43% de l’offre marchande • Les campings constituent le second type d’’établissements avec 2 200 lits (18% des lits marchands) Le mode de comptage des lits touristiques (en particulier non marchands) ayant été modifié, la comparaison avec les données des années antérieures n’est pas réalisable. Chiffres disponibles au 30/06/2021 1/7 FREQUENTATION DES HEBERGEMENTS MARCHANDS : L’HOTELLERIE Source : INSEE - DGE NB1 : en 2019, l’INSEE a modifié les modalités de l’enquête hôtellerie entraînant une rupture de série statistique. Les données ont été recalculées depuis 2012. Les séries publiées antérieurement ne doivent pas être comparées à cette nouvelle série. NB2 : en 2020, la crise sanitaire a impacté l’ouverture des établissements et suspendu le déroulement des enquêtes de fréquentation de l’INSEE. -

Plan De Prévention Des Risques Naturels Prévisibles De La Commune De Montmin

PRÉFECTURE DE LA HAUTE-SAVOIE PLAN DE PRÉVENTION DES RISQUES NATURELS PRÉVISIBLES DE LA COMMUNE DE ONTMIN M Note de présentation RISQUES MAJEURS ET ENVIRONNEMENT Mai 2015 Table des matières PREAMBULE 1 Présentation du P.P.R. ................................................................................................................................................................................................... 7 2 Rappel réglementaire ..................................................................................................................................................................................................... 7 2.1 Objet du PPR .......................................................................................................................................................................................................... 7 2.2 Prescription du PPR ............................................................................................................................................................................................... 8 2.3 Contenu du P.P.R. ................................................................................................................................................................................................... 9 2.4 Approbation, révision et modification du P.P.R. .................................................................................................................................................. 9 3 Pièces du dossier .......................................................................................................................................................................................................... -

Atlas Linguistique Audiovisuel Du Francoprovençal Valaisan

ATLAS LINGUISTIQUE AUDIOVISUEL DU FRANCOPROVENÇAL VALAISAN 2 Centre de dialectologie et d’étude du français régional de l’Université de Neuchâtel ATLAS LINGUISTIQUE AUDIOVISUEL DU FRANCOPROVENÇAL VALAISAN Questions de morphologie et de syntaxe francoprovençales Réalisé par: Elisabeth Berchtold, Gisèle Boeri, Steve Bonvin, Federica Diémoz, Andres Kristol, Raphaël Maître, Chiara Marquis, Gisèle Pannatier, Aurélie Reusser-Elzingre, Maguelone Sauzet Avec la collaboration de: Luc Allemand, Simone Aubry-Quenet, Anne-Gabrielle Bretz-Héritier, Beat Butz, Marie Canetti, Maude Ehinger, Samantha Formaz, Frédéric Geiser, Christelle Godat, Gabriel Grossert, Laure Grüner, Nathaniël Hiroz, Antoine Imhoff, Amélie Jeandel, Valérie Kobi, Catherine Kristol, Laura di Lullo, Magda Jezioro, Elise Neyroud, Lucas Paccaud, Joanna Pauchard, Quentin Perissinotto, Manuel Riond, Andrea Rolando, Michaël Roulet, Anna Schwab Développement et support informatique : Pierre Ménétrey Sous la direction de: Federica Diémoz & Andres Kristol Neuchâtel 2019 3 4 À la mémoire d’une langue qui s’en va Avec l’expression de notre profonde gratitude envers toutes nos informatrices et nos informateurs Réalisé sur la base d’un projet Interreg II Valais-Vallée d’Aoste, en partenariat avec la Bibliothèque cantonale du Valais (Centre valaisan de l’image et du son, Martigny) et le Bureau régional d’ethnographie et de linguistique B.R.E.L. de la région autonome Vallée d’Aoste, avec le soutien de Loterie romande, de l’Association William Pierrehumbert (Neuchâtel) et du Fonds national suisse de la recherche scientifique. 5 6 Table des matières I. Introduction 1. Le francoprovençal valaisan 15 2. Histoire de la recherche 17 3. Méthodologie, objectifs 19 3.1. Objectifs 19 3.2. Questionnaire, méthode d’enquête, problèmes techniques 23 4. -

Bassin Albanais – Annecien

TABLEAU I : BASSIN ALBANAIS – ANNECIEN COLLEGES COMMUNES ET ECOLES René Long ALBY -SUR -CHERAN ; ALLEVES ; CHAINAZ -LES -FRASSES ; CHAPEIRY ; CUSY ; GRUFFY ; HERY -SUR -ALBY ; MURES ; SAINT - ALBY-SUR-CHERAN SYLVESTRE ; VIUZ-LA-CHIESAZ Les Balmettes ANNECY - Annecy : groupes scolaires Vaugelas, La Prairie, Quai Jules Philippe (selon un listing de rues précis – cf. Conseil ANNECY- ANNECY Départemental ou collège) ANNECY- Annecy : groupes scolaires Carnot, La Plaine (selon un listing de rues précis – cf. Conseil Départemental ou collège) , Le Raoul Blanchard Parmelan (selon un listing de rues précis – cf. Conseil Départemental ou collège), Les Romains, Quai Jules Philippe (selon un ANNECY- ANNECY listing de rues précis – cf. Conseil Départemental ou collège), Vallin-Fier (selon un listing de rues précis – cf. Conseil Départemental ou collège) Les Barattes ANNECY- Annecy : groupes scolaires Le Parmelan (selon un listing de rues précis – cf. Conseil Départemental ou collège), Novel (selon un listing de rues précis – cf. Conseil Départemental ou collège); ANNECY- Annecy-le-Vieux (selon un listing de rues ANNECY- ANNECY-LE-VIEUX précis – cf. Conseil Départemental ou collège); BLUFFY ; MENTHON-SAINT-BERNARD ; TALLOIRES-MONTMIN ; VEYRIER-DU-LAC ANNECY-Annecy : groupes scolaires Vallin-Fier (selon un listing de rues précis – cf. Conseil Départemental ou collège), La Plaine Evire (selon un listing de rues précis – cf. Conseil Départemental ou collège), Novel (selon un listing de rues précis – cf. Conseil ANNECY- ANNECY-LE-VIEUX Départemental ou -

PROJET DE REPRISE DU JOURNAL « LE FAUCIGNY » Janvier 2014 Noël Communod

PROJET DE REPRISE DU JOURNAL « LE FAUCIGNY » Janvier 2014 Noël Communod CHRONIQUES DES PAYS DE SAVOIE Histoire du Faucigny (Wikipedia) Le Faucigny est un hebdomadaire savoyard édité à Bonneville (capitale de l'ancienne province du Faucigny). Né à la Libération, en 1944, il est le successeur du journal L’Allobroge, créé en 1864, au lendemain de l’Annexion de la Savoie (à ne pas confondre avec Les Allobroges, quotidien régional de gauche, publiées à Grenoble de la Libération jusqu’au milieu des années 1950). L’Allobroge fusionna dans les années 1920 avec Le Mont-Blanc républicain, de même sensibilité politique (républicain, laïc et anticlérical). Après la Seconde Guerre mondiale, le journal change de nom comme pour signifier un renouveau. Le Faucigny est né. Adoptant dans les années 1980 un ton satirique, qui fera son succès, il est souvent comparé avec Le Canard enchaîné. On y retrouve Les Indiscrétions de Charles-Félix, une rubrique particulièrement lue par les décolleteurs de la vallée de l’Arve et les élus locaux de Haute-Savoie. Principalement centré autour de la vie politique locale, le journal aborde également des sujets plus généralistes (politique, justice, aménagement du territoire...). LA SITUATION Le propriétaire, Pierre Plancher, est décédé il y a quelques mois. Le Faucigny est aujourd’hui dirigé par son frère qui ne souhaite pas le garder et qui voudrait que l’esprit insufflé par son frère se poursuive. Hebdomadaire de 8 à 12 pages vendu 1,10 € au numéro et 47 € l’abonnement annuel. Trois journalistes : Messieurs Bertoni et Coste et madame Varvier Une personne chargée de l’administration : Madame Cousin Le journal est hébergé dans les locaux de la société Plancher (au coût minimal) et imprimé dans l’imprimerie Plancher. -

3B2 to Ps Tmp 1..96

1975L0271 — EN — 14.04.1998 — 014.001 — 1 This document is meant purely as a documentation tool and the institutions do not assume any liability for its contents ►B COUNCIL DIRECTIVE of 28 April 1975 concerning the Community list of less-favoured farming areas within the meaning of Directive No 75/268/EEC (France) (75/271/EEC) (OJ L 128, 19.5.1975, p. 33) Amended by: Official Journal No page date ►M1 Council Directive 76/401/EEC of 6 April 1976 L 108 22 26.4.1976 ►M2 Council Directive 77/178/EEC of 14 February 1977 L 58 22 3.3.1977 ►M3 Commission Decision 77/3/EEC of 13 December 1976 L 3 12 5.1.1977 ►M4 Commission Decision 78/863/EEC of 9 October 1978 L 297 19 24.10.1978 ►M5 Commission Decision 81/408/EEC of 22 April 1981 L 156 56 15.6.1981 ►M6 Commission Decision 83/121/EEC of 16 March 1983 L 79 42 25.3.1983 ►M7 Commission Decision 84/266/EEC of 8 May 1984 L 131 46 17.5.1984 ►M8 Commission Decision 85/138/EEC of 29 January 1985 L 51 43 21.2.1985 ►M9 Commission Decision 85/599/EEC of 12 December 1985 L 373 46 31.12.1985 ►M10 Commission Decision 86/129/EEC of 11 March 1986 L 101 32 17.4.1986 ►M11 Commission Decision 87/348/EEC of 11 June 1987 L 189 35 9.7.1987 ►M12 Commission Decision 89/565/EEC of 16 October 1989 L 308 17 25.10.1989 ►M13 Commission Decision 93/238/EEC of 7 April 1993 L 108 134 1.5.1993 ►M14 Commission Decision 97/158/EC of 13 February 1997 L 60 64 1.3.1997 ►M15 Commission Decision 98/280/EC of 8 April 1998 L 127 29 29.4.1998 Corrected by: ►C1 Corrigendum, OJ L 288, 20.10.1976, p.