The Einsteins of Wall Street Jeremy Bernstein

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Speaker Biographies

The Quantitative Revolution and the Crisis: How Have Quantitative Financial Models Been Used and Misused Speaker Biographies Hugh Patrick is Director of the Center on Japanese Economy and Business at Columbia Business School, co-director of Columbia’s APEC Study Center, and R.D. Calkins Professor of International Business Emeritus. He joined the Columbia faculty in 1984 after some years as Professor of Economics and Director of the Economic Growth Center at Yale University. He has been a visiting professor at Hitotsubashi University, University of Tokyo, and University of Bombay. Professor Patrick has been awarded Guggenheim and Fulbright fellowships and the Ohira Prize. His professional publications include sixteen books and some sixty articles and essays. He is on the Board of Directors of the U.S. Asia Pacific Council and is a member of the Council of Foreign Relations. In November 1994, the Government of Japan awarded him the Order of the Sacred Treasure, Gold and Silver Star (KunnitôZuihôshô). He completed his B.A. at Yale University in 1951, earned M.A. degrees in Japanese Studies (1955) and Economics (1957) and a Ph.D. in Economics at the University of Michigan in 1960. Bruce Kogut is the Sanford C. Bernstein & Co. Professor of Leadership and Ethics and director of the Sanford C. Bernstein Center for Leadership and Ethics at Columbia Business School. He received his Ph.D. from the MIT Sloan School of Management and holds an honorary doctorate from the Stockholm School of Economics. Previously, he was on the faculties of the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania and INSEAD, and he has been a research fellow and visiting professor at the Rand Corporation, École Polytechnique, Social Science Research Center Berlin, Stockholm School of Economics, among others. -

Paul Wilmott Introduces Quantitative Finance

Paul Wilmott Introduces Quantitative Finance Second Edition Paul Wilmott Introduces Quantitative Finance Second Edition www.wilmott.com Copyright ≤ 2007 John Wiley & Sons Ltd, The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex PO19 8SQ, England Telephone (+44) 1243 779777 Email (for orders and customer service enquiries): [email protected] Visit our Home Page on www.wiley.com Copyright ≤ 2007 Paul Wilmott All Rights Reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning or otherwise, except under the terms of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 or under the terms of a licence issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency Ltd, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London W1T 4LP, UK, without the permission in writing of the Publisher. Requests to the Publisher should be addressed to the Permissions Department, John Wiley & Sons Ltd, The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex PO19 8SQ, England, or emailed to [email protected], or faxed to (+44) 1243 770620. Designations used by companies to distinguish their products are often claimed as trademarks. All brand names and product names used in this book are trade names, service marks, trademarks or registered trademarks of their respective owners. The Publisher is not associated with any product or vendor mentioned in this book. This publication is designed to provide accurate and authoritative information in regard to the subject matter covered. It is sold on the understanding that the Publisher is not engaged in rendering professional services. If professional advice or other expert assistance is required, the services of a competent professional should be sought. -

A Simple Model for Pricing Securities with Equity, Interest-Rate, and Default Risk∗

A Simple Model for Pricing Securities with Equity, Interest-Rate, and Default Risk∗ Sanjiv R. Das Rangarajan K. Sundaram Santa Clara University New York University Santa Clara, CA 95053 New York, NY 10012. June 2002, November 2003; Current version: October 2004. ∗The authors’ respective e-mail addresses are [email protected], and [email protected]. We owe a huge debt of grati- tude for extensive discussions and correspondence with Suresh Sundaresan and Mehrdad Noorani. We are very grateful for the use of data from CreditMetrics. Our thanks also to Jan Ericsson, Kian Esteghamat, Rong Fan, Gary Geng, and Maxime Popineau for several helpful comments. The paper benefitted from the comments of seminar participants at York University, New York University, University of Oklahoma, Stanford University, Santa Clara University, Universita La Sapienza, Cred- itMetrics, MKMV Corp., the 2003 European Finance Association Meetings in Glasgow, Morgan Stanley, Archeus Capital Management, Lehman Brothers, and University of Massachusetts, Amherst. 1 Equity, Interest-rate, Default Risk . .2 A Simple Model for Pricing Securities with Equity, Interest-Rate, and Default Risk Abstract We develop a model for pricing derivative and hybrid securities whose value may depend on dif- ferent sources of risk, namely, equity, interest-rate, and default risks. In addition to valuing such secu- rities the framework is also useful for extracting probabilities of default (PD) functions from market data. Our model is not based on the stochastic process for the value of the firm, which is unobservable, but on the stochastic processes for interest rates and the equity price, which are observable. The model comprises a risk-neutral setting in which the joint process of interest rates and equity are modeled to- gether with the default conditions for security payoffs. -

Course Syllabus

Course Syllabus University of Pennsylvania The Wharton School Operations, Information and Decisions Mathematical Modeling and its Application in Finance OIDD 353/653 – Spring 2018 Tuesday & Thursday, 3:00pm - 6:00pm January 11 – February 27, 2018 Room: TBD JMHH Office Hours: Tue & Thu 1:30-2:45pm or by appointment Professor Ziv Katalan Office: 3454 SHDH Phone (215) 898-7290 Cell (215) 715-5676 email: [email protected] Teaching Assistant: TBD Modern financial markets are marked by the widespread prevalence of new financial products, the importance of risk management, and the availability of powerful computational technology. Quantitative methods have become fundamental tools in the analysis and planning of financial operations. There are many reasons for this development: the emergence of a whole range of new and complex financial instruments, innovations in securitization, the increased globalization of the financial markets, the proliferation of information technology, and so on. In this class, we develop financial models and computational methods to solve pricing, hedging, and portfolio optimization problems that appear every day in financial markets. The emphasis is on a practical approach: we apply models and methods in a hands-on fashion to real problems, and simultaneously highlight their limitations in real situations. We develop techniques to price a wide array of equity derivatives, including path-dependent options and multi-asset options. We explore the related problems of hedging and risk management, and we address issues that arise in short and long term portfolio optimization. We construct models for the evolution of interest rates, to allow for the pricing and hedging of interest rate derivatives. -

Cutting-Edge Innovations in Derivatives Pricing, Hedging

Nobel Special 10th Annual Meeting Laureate Special Guest Address Discounts For Robert Engle, NYU Institutional Investors STERN SCHOOL OF BUSINESS & NOBEL Cutting-Edge Innovations In Derivatives LAUREATE Pricing, Hedging, Trading & Portfolio Management Plus! For Over 100+ Investment & Commercial Banks, Fund Managers, Speakers Including: Hedge Funds & Institutional Investors I Goldman Sachs I Renaissance Technologies Plus! Don’t Miss Presentations From These Renowned Global Financial Minds I Royal Bank Of Scotland I Merrill Lynch I Deutsche Bank I BNP Paribas I JPMorgan Chase I DrKW I Pioneer Alternative Investments I Abbey I NYU Stern School of Business I UBS I Societe Generale Peter Carr John Hull Riccardo Emanuel Derman, Nassim Taleb Robert Shiller, Bill Fung , , , , I Lehman Brothers Head of Quantitative Professor of Rebonato, Professor of Finance Founder Professor of Visiting Professor Research Derivatives & Risk Head of Group COLUMBIA EMPIRICA Economics LONDON I University of Toronto BLOOMBERG Management Market Risk UNIVERSITY CAPITAL YALE BUSINESS I HSBC UNIVERSITY ROYAL BANK OF UNIVERSITY SCHOOL I Clinton Group OF TORONTO SCOTLAND I Optioncity.net I Laurel Ridge Asset Management Plus! Expert Insights From These Leading Derivatives Practitioners I Citigroup I Mako Investment Managers I JD Capital Management I Uniqa Alternative Investments I Olsen I CONSOB I WestLB I Bloomberg I Moodys KMV I Willowbridge Associates I Freddie Mac Rajeev Misra, Andrew Harmstone, Rick Shypit, Martin St-Pierre, Jim Gatheral, Marek Musiela, Steve Ross, -

International Association for Quantitative Finance

INTERNATIONAL ASSOCIATION FOR QUANTITATIVE FINANCE SENIOR FELLOWS About the IAQF, the GCARD’s Inaugural Professional Society Partner Phelim Boyle (formerly the IAFE) Wilfrid Laurier University The International Association for Quantitative Finance is the professional society dedicated to fostering the profession of quantitative finance by Douglas Breeden Duke University providing platforms for the discussion of cutting-edge and pivotal issues in the field. Michael Brennan Founded in 1992, the IAQF is composed of individual academics and practitioners from Manchester University UCLA banks, broker dealers, hedge funds, pension funds, asset management firms, technology Peter Carr firms, regulatory bodies, accounting, consulting and law firms, and universities across the NYU Tandon globe. John C. Cox MIT Sloan School of Management Through frank discussions of current policy issues, hosting programs to educate the Emanuel Derman finance community, and recognizing the outstanding achievements in the field, the IAQF Columbia University acts as a beacon for the development of quantitative finance. Throughout its history, the Darrell Duffie Stanford University IAQF’s pre-eminent leadership has positioned us to respond with savvy to the evolving Robert Engle needs of the financial engineering community. The IAQF’s programs – from our area- New York University specific committees to our evening forums to the Financial Engineer of the Year Award – John C. Hull are designed to provide our membership with uniquely valuable activities to enhance University of Toronto their work in the field. Jonathan Ingersoll Yale University Why Join the IAQF? Robert Jarrow Cornell University As ever more attention is focused on quantitative finance, the IAQF stands out as the Martin L. -

Implementation of the Black, Derman and Toy Model

Implementation of the Black, Derman and Toy Model Seminar Financial Engineering o.Univ.-Prof. Dr. Engelbert J. Dockner University of Vienna Summer Term 2003 Christoph Klose Li Chang Yuan Implementation of the Black, Derman and Toy Model Page 2 Contents of this paper Contents of this paper....................................... 2 1. Introduction to Term Structure Models..................... 3 2. Term Structure Equation for Continuous Time............... 4 3. Overview - Basic Processes of One-Factor Models........... 7 4. The Black Derman and Toy Model (BDT)...................... 8 4.1. Characteristics......................................... 8 4.2. Modeling of an “artificial” Short-Rate Process.......... 9 Valuing Options on Treasury Bonds ....................... 13 4.3. The BDT-Model and Reality.............................. 16 5. Implementation and Application of the BDT-Model.......... 19 6. List of Symbols and Abbreviations........................ 23 7. References............................................... 24 8. Suggestions for further reading.......................... 25 Implementation of the Black, Derman and Toy Model Page 3 1. Introduction to Term Structure Models Interest rate derivatives are instruments that are in some way contingent on interest rates (bonds, swaps or just simple loans that start at a future point in time). Such securities are extremely important because almost every financial transaction is exposed to interest rate risk – and interest rate derivatives provide the means for controlling this risk. In addition, same as with other derivative securities, interest rate derivatives may also be used to enhance the performance of investment portfolios. The interesting and crucial question is what are these instruments worth on the market and how can they be priced. In analogy to stock options, interest rate derivatives depend on their underlying, i.e. -

The Volatility Smile Emanuel Derman, Michael B

To purchase this product, please visit https://www.wiley.com/en-al/9781118959183 The Volatility Smile Emanuel Derman, Michael B. Miller, David Park (Contributions by) E-Book 978-1-118-95918-3 August 2016 €54.99 Hardcover 978-1-118-95916-9 October 2016 €72.70 O-Book 978-1-119-28925-8 August 2016 Available on Wiley Online Library DESCRIPTION The Volatility Smile The Black-Scholes-Merton option model was the greatest innovation of 20th century finance, and remains the most widely applied theory in all of finance. Despite this success, the model is fundamentally at odds with the observed behavior of option markets: a graph of implied volatilities against strike will typically display a curve or skew, which practitioners refer to as the smile, and which the model cannot explain. Option valuation is not a solved problem, and the past forty years have witnessed an abundance of new models that try to reconcile theory with markets. The Volatility Smile presents a unified treatment of the Black-Scholes-Merton model and the more advanced models that have replaced it. It is also a book about the principles of financial valuation and how to apply them. Celebrated author and quant Emanuel Derman and Michael B. Miller explain not just the mathematics but the ideas behind the models. By examining the foundations, the implementation, and the pros and cons of various models, and by carefully exploring their derivations and their assumptions, readers will learn not only how to handle the volatility smile but how to evaluate and build their own financial models. -

A Foundation for Quantitative Finance: from Randomness Engineering to Financial Engineering”

“A Foundation for Quantitative Finance: From randomness engineering to financial engineering” R. B. Holmes, PhD HIM&R, Inc. [email protected] Abstract At the center of most efforts in quantitative finance is an asset price model. We address the questions: Where do models come from? What do you want from a model? How do you validate a model? What can you do with a model, once accepted? This subject has had, of course, a long and controversial history, dating back over 40 years. Here we want to emphasize recent data-based approaches, part of what has become a new interdisciplinary field, now known as “econophysics”. Indeed, it’s a bold and fascinating notion, given the diversity of markets, time periods, sampling frequency, etc., that there may be some intrinsic (even universal!) properties of financial data that can in turn be captured by suitable statistical models,. Once fixed, a model can be used to create an artificial “simworld” wherein financial strategies can be tested, derivative models priced, etc. Here there are both top- down and bottom-up approaches, the latter an attempt to “explain” the model, in much the same way as atomic structure can explain macro-observables in physics. In either case, given that the model posits that prices are somehow made out of noise, then noise can be used to create (artificial) prices via simulation, if we can create noise. This last is a more subtle problem than perhaps one intuitively would expect… 1 Financial engineering ------------- ----------------- Ideal world of MODELS Simulation and other techniques ---------------- ------------- Randomness engineering 2 The Classic Conundrum of Science “There are two ways of forming an opinion. -

Models. Behaving. Badly

Derman_Models_i-218_PTR.indd 232 8/18/11 3:05 PM MODELS.BEHAVING.BADLY. ffirs.indd i 9/15/2011 4:45:51 PM ALSO BY EMANUEL DERMAN My Life as a Quant: Refl ections on Physics and Finance ffirs.indd ii 9/15/2011 4:45:52 PM MODELS.BEHAVING.BADLY. Why Confusing Illusion with Reality Can Lead to Disaster, on Wall Street and in Life EMANUEL DERMAN A John Wiley & Sons, Ltd., Publication ffirs.indd iii 9/15/2011 4:45:52 PM Th is edition fi rst published in 2011 Copyright © 2011 by Emanuel Derman Registered offi ce John Wiley & Sons Ltd, Th e Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, United Kingdom For details of our global editorial offi ces, for customer services and for information about how to apply for permission to reuse the copyright material in this book please see our website at www.wiley.com. Th e right of Emanuel Derman to be identifi ed as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. First published in the United States by Free Press, A Division of Simon & Schuster, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, without the prior permission of the publisher. Wiley also publishes its books in a variety of electronic formats. Some content that appears in print may not be available in electronic books. -

Hayne Leland Selected As the Recipient of the 2016 IAQF/Northfield John C

For more information, please contact: Northfield Douglas Spencer +1-774-260-5560 [email protected] SENIOR FELLOWS IAQF Phelim Boyle David Jaffe Wilfrid Laurier University +1-646-736-0705 [email protected] Peter Carr New York University Hayne Leland Selected as the Recipient of the 2016 IAQF/Northfield John C. Cox Financial Engineer of the Year Award MIT Sloan School of Management Emanuel Derman December 2, 2016 – New York – The International Association for Quantitative Columbia University Finance (IAQF) and Northfield have named Hayne Leland, Professor of the Darrell Duffie Graduate School at the University of California, Berkeley's Haas School of Stanford University Business, the 2016 IAQF/Northfield Financial Engineer of the Year (FEOY). The Robert Engle award will be presented to Professor Leland on February 2, 2017, at the Yale NYU, Stern School of Business Club in New York City, during the IAQF/Northfield FEOY Award Gala Dinner. John C. Hull A pioneer in the field of modern corporate finance, Hayne Leland has led University of Toronto research on option pricing, capital structure and risk management and has Jonathan Ingersoll influenced the fields of banking, asset pricing, bond valuation, portfolio Yale University management, and portfolio insurance over nearly 50 years. Robert Jarrow Cornell University Upon his acceptance of the award Leland remarked, “To be selected to join Bob Litterman such a distinguished group of prior FEOY recipients is indeed a great honor. Kepos Capital That this honor is awarded by a committee of distinguished industry Robert Litzenberger professionals as well as academics brings me special pleasure, as I believe a University of Pennsylvania hallmark of good research is its ultimate usefulness to practitioners in the field.” Andrew Lo Northfield President Dan diBartolomeo agrees: “Professor Leland is one of a MIT Sloan School of Management small circle in the history of modern finance who has had a profound influence Harry Markowitz on both theory and practice across the entire range of investment Harry Markowitz Co. -

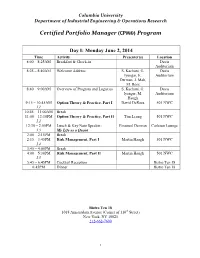

Certified Portfolio Manager (CPM®) Program

Columbia University Department of Industrial Engineering & Operations Research Certified Portfolio Manager (CPM®) Program Day I: Monday June 2, 2014 Time Activity Presenter(s) Location 8:00 – 8:25AM Breakfast & Check-in Davis Auditorium 8:25 – 8:40AM Welcome Address S. Kachani, G. Davis Iyengar, E. Auditorium Derman, J. Mak, M. Ross 8:40 – 9:00AM Overview of Program and Logistics S. Kachani, G. Davis Iyengar, M. Auditorium Haugh 9:15 – 10:45AM Option Theory & Practice, Part I David DeRosa 501 NWC I.1 10:45 – 11:00AM Break 11:00 – 12:30PM Option Theory & Practice, Part II Tim Leung 501 NWC I.2 12:30 – 2:00PM Lunch & Key Note Speaker: Emanuel Derman Carleton Lounge I.3 My Life as a Quant 2:00 – 2:15PM Break 2:15 – 3:45PM Risk Management, Part I Martin Haugh 501 NWC I.4 3:45 – 4:00PM Break 4:00 – 5:30PM Risk Management, Part II Martin Haugh 501 NWC I.5 5:45 – 6:45PM Cocktail Reception Bistro Ten 18 6:45PM Dinner Bistro Ten 18 Bistro Ten 18 1018 Amsterdam Avenue (Corner of 110th Street) New York, NY 10025 212-662-7600 1 Columbia University Department of Industrial Engineering & Operations Research Certified Portfolio Manager (CPM®) Program Day II: Tuesday June 3, 2014 Time Activity Presenter(s) Location 8:30 – 9:05AM Breakfast & Check-in Carleton Lounge 9:15 – 10:45AM Asset Allocation, Part I Garud Iyengar 501 NWC II.1 10:45 – 11:00AM Break 11:00 – 12:30PM Asset Allocation, Part II Garud Iyengar 501 NWC II.2 12:30 – 2:00PM Lunch & Key Note Speaker: James Grant Carleton Lounge II.3 Bringing back the Gold Standard 2:00 – 2:15PM Break 2:15 – 3:45PM.