Socioeconomic Wellbeing Main Report, Nov 2019

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mill End Millthrop 1 Sedbergh 1 LA10 5SJ Mill End

Mill End Millthrop 1 Sedbergh 1 LA10 5SJ Mill End Dating back to the 19th century, Mill End sits along a private driveway within a small community of similar properties at Millthrop, a short distance by car or level walk on foot from Sedbergh. This cleverly converted former mill building offers versatile accommodation across two floors which would suit either the permanent or secondary residence purchaser and provides good views of Winder Fell, part of Wainwright’s beloved Howgill range. Included in the sale are private fishing rights to the River Rawthey, direct access being available from the secluded, riverside garden here at Mill End. Just 5 miles from junction 37 of the M6 and 10 miles from Auld Grey town of Kendal, Sedbergh is well placed in terms of road access to both the Lake District and Yorkshire Dales national park. Public transport options are numerous with Oxenholme Main line only 10 miles away. Private and independent schooling for primary and secondary stages are easily accessible and a host of modern day amenities and open air, weekly market are available in Sedbergh, England’s official ‘book town’. Millthrop is on the famous Dales Way, an 80 mile walk from Ilkley to Bowness on Windermere, popular with tourists throughout the year. The accommodation at Mill End is currently set out over two floors with kitchen and bathroom facilities to each level. However, the layout does offer several options for re-working the existing design of the three bedrooms, two spacious bathrooms and two kitchens to suit the purchaser’s individual requirements and to make best use of the available space. -

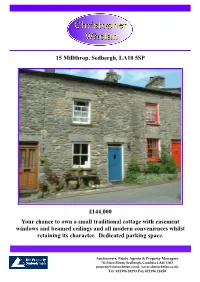

15 Millthrop, Sedbergh, LA10 5SP £144,000 Your Chance to Own A

15 Millthrop, Sedbergh, LA10 5SP £144,000 Your chance to own a small traditional cottage with casement windows and beamed ceilings and all modern conveniences whilst retaining its character. Dedicated parking space. Auctioneers, Estate Agents & Property Managers 70, Main Street, Sedbergh, Cumbria LA10 5AD [email protected] www.chriswhelan.co.uk Tel: 015396 20293 Fax 015396 21650 Accommodation (All measurements are approximate) Stairs Up to half landing with door to garden then up again. Kitchen 1.83 x 1.98m (6ft 0ins x 6ft 6ins) Range of wall and base units with stainless steel 1 ½ Bathroom 2.41 x 2.11m (7ft 11ins x 6ft 11ins) bowl sink. Space for fridge and cooker. Tile splash. Panel bath with electric shower over. WC. Pedestal Tiled floor. Cupboard under stairs housing Vaillant basin. Tile splash. Radiator. Carpet. Combi gas boiler. Bedroom 2.84 x 3.66m (9ft 4ins x 12ft 0ins) Lounge/diner 3.43 x 3.61m (11ft 3ins x 11ft 10ins) Built in cupboard. Radiator. Carpet. Gas fired stove. Built in cupboard. Carpet. Radiator. Stairs up to Attic 3.91 x 3.48m (12ft 10ins x 11ft 5ins) Veluxe rooflight. Radiator. Carpet. Storage under eaves. Entrance Vestibule Directions From Sedbergh take the road towards Dent, cross the bridge over the River Rawthey then take first left to Millthrop. At the top of road turn right and follow road through hamlet. No 15 is on the right. Local Authorities: South Lakeland District Council, Kendal. Cumbria County Council, Carlisle Planning Authority: Yorkshire Dales National Park, Yoredale, Bainbridge, Leyburn. N.Yorkshire DL8 3EL. -

With St. Peter's, Hebden

With St. Peter’s, Hebden Annual Parochial Church Meeting 15th November 2020 Reports Booklet The Parish of Linton St. Michael’s & All Angels, Linton St. Peter’s, Hebden Church Officials Rector Rev David Macha Reader Cath Currier PCC Secretary Vacancy Church Wardens Rory Magill Helen Davy Mark Ludlum Valerie Ludlum Treasurer Maureen Chaduc Deanery Synod Representatives Lesley Brooker Jennie Scott Lay Members Neil McCormac Betty Hammonds Jane Sayer Jacqui Sugden + 5 Vacancies Sidespersons Rita Clark Ian Clark Betty Hammonds Dennis Leeds Bunty Leder Valerie Ludlum Phyllida Oates Bryan Pearson Pamela Whatley-Holmes John Wolfenden Joan Whittaker Muriel White Brian Metcalfe Mary Douglas Ian Simpson The Parish of Linton St. Michael’s & All Angels, Linton St. Peter’s, Hebden Meeting of Parishioners – 15th November 2020 Agenda Minutes of Meeting of Parishioners 2019 Election of Churchwardens Annual Parochial Church Meeting – 15th November 2020 Agenda 1 Apologies for absence 2 Reception of the Electoral Roll 3 Election of Laity to the Parochial Parish Council and to the Deanery Synod 4 Appointment of Sidepersons 5 Approval of 2019 APCM Minutes 7 2019 Annual Accounts – Receipt of and Acceptance of Independent Examiner’s Statement for 2019 accounts 8 Annual Reports in booklets 9 Chairman’s Address 10 AOB & Questions Electoral Roll Information at 6th October 2020 There are 64 names on the Electoral Roll for 2020. This is an increase of one from 2019 and comprises 55 resident in the parish and 9 not resident in the parish. The electronic publication of the Electoral Roll on the Linton parish website undoubtedly contributed to the low level of revisions and no removals were notified. -

Happy Easter to All from Your Local News Magazine for the Two Dales PRICELESS

REETH AND DISTRICT GAZETTE LTD ISSUE NO. 193 APRIL 2012 Happy Easter to all from your local news magazine for the Two Dales PRICELESS 2 REETH AND DISTRICT GAZETTE LTD CHURCH NOTICES in Swaledale & Arkengarthdale st 1 April 9.15 am St. Mary’s Muker Eucharist - Palm Sunday 10.30 am Low Row URC Reeth Methodist 11.00 am Holy Trinity Low Row Eucharist St. Edmund’s Marske Reeth Evangelical Congregational Eucharist 2.00 pm Keld URC 6.00 pm St. Andrew’s, Grinton Evening Prayer BCP 6.30 pm Gunnerside Methodist Reeth Evangelical Congregational th 5 April 7.30 pm Holy Trinity Low Row Eucharist & Watch 8.00 pm St. Michael’s Downholme Vigil th 6 April 9.00 am Keld – Corpse Way Walk - Good Friday 11.00 am Reeth Evangelical Congregational 12.00 pm St Mary’s Arkengarthdale 2.00 pm St. Edmund’s Marske Devotional Service 3.00 pm Reeth Green Meet 2pm Memorial Hall Open Air Witness th 7 April – Easter Eve 8.45 pm St. Andrew’s, Grinton th 8 April 9.15 am St. Mary’s, Muker Eucharist - Easter Sunday 9.30 am St. Andrew’s, Grinton Eucharist St. Michael’s, Downholme Holy Communion 10.30 am Low Row URC Holy Communion Reeth Methodist All Age Service 11.00 am Reeth Evangelical Congregational St. Edmund’s Marske Holy Communion Holy Trinity Low Row Eucharist 11.15 am St Mary’s Arkengarthdale Holy Communion BCP 2.00 pm Keld URC Holy Communion 4.30 pm Reeth Evangelical Congregational Family Service followed by tea 6.30 pm Gunnerside Methodist with Gunnerside Choir Arkengarthdale Methodist Holy Communion th 15 April 9.15 am St. -

Fell Cottage, Marsett, Nr Lake Semerwater (Lot 3/3)

Hawes 01969 667744 Bentham 01524 26 2044 Leyburn 01969 622936 Settle 01729 825311 www.jrhopper.com Market Place, Leyburn London 02074 098451 North Yorkshire DL8 5BD [email protected] “For Sales In The Dales” 01969 622936 Fell Cottage, Marsett, Nr Lake Semerwater (lot 3/3) Barn Conversion Low Maintenance Garden Excellent Bolt Hole Or Multi-Fuel Stove Parking For 2 Cars Holiday Let Two Double Bedrooms Rural Location With Viewing Highly Both En-suite Stunning Views Recommended Offers Around £205,000 RESIDENTIAL SALES • LETTINGS • COMMERCIAL • PROPERTY CONSULTANCY Valuations, Surveys, Planning, Commercial & Business Transfers, Acquisitions, Conveyancing, Mortgage & Investment Advice, Inheritance Planning, Property, Antique & Household Auctions, Removals J. R. Hopper & Co. is a trading name for J. R. Hopper & Co. (Property Services) Ltd. Registered: England No. 3438347. Registered Office: Hall House, Woodhall, DL8 3LB. Directors: L. B. Carlisle, E. J. Carlisle Fell Cottage, Marsett, Nr. Lake Semerwater DESCRIPTION Fell Cottage is a delightful barn conversion in the tiny hamlet of Marsett up in Raydale, at the southern end of Lake Semerwater, the largest natural lake in Yorkshire, but quite undiscovered. The property is tucked away down a private track. Marsett itself has 3 working farms in and around the hamlet as well as a seasonal campsite for tents only. The hamlet also benefits from high speed broadband. Raydale is a little Dale of Wensleydale and Marsett and lies only 3.5 miles from the village of Bainbridge and 5.5 miles from the popular market town of Hawes. It enjoys an abundance of wildlife and is great for bird watching, fishing and walkers wishing to set off straight from the cottage doorstep! Hawes is a thriving market town with a good range of shops, restaurants, tea rooms and pubs. -

Stable Cottage, Barn & Campsite, Marsett, Nr Lake Semerwater

Hawes 01969 667744 Bentham 01524 26 2044 Leyburn 01969 622936 Settle 01729 825311 www.jrhopper.com Market Place, Leyburn London 02074 098451 North Yorkshire DL8 5BD [email protected] “For Sales In The Dales” 01969 622936 Stable Cottage, Barn & Campsite, Marsett, Nr Lake Semerwater (lot 2/3) Dales House, Land & Stables Dining Room Detached Barn/Stables Delightful Barn Conversion Modern Fitted Kitchen Ample Parking Rural Yet Accessible Location Boot Room Double Glazing 3 Double Bedrooms Wet Room & Downstairs WC Patio & Garden Living Room with Bi-Fold Doors Ap prox 5 Acres Of Land used as Fantastic Views & Multi Fuel Stove a Tented Campsite Ideal Family Home Or Business Opportunity Offers Around £500,000 RESIDENTIAL SALES • LETTINGS • COMMERCIAL • PROPERTY CONSULTANCY Valuations, Surveys, Planning, Commercial & Business Transfers, Acquisitions, Conveyancing, Mortgage & Investment Advice, Inheritance Planning, Property, Antique & Household Auctions, Removals J. R. Hopper & Co. is a trading name for J. R. Hopper & Co. (Property Services) Ltd. Registered: England No. 3438347. Registered Office: Hall House, Woodhall, DL8 3LB. Directors: L. B. Carlisle, E. J. Carlisle Stable Cottage, Barn & Campsite, Marsett, Nr Lake Semerwater DESCRIPTION Lot 1 – Stable Cottage, Fell Cottage, Barn and Campsite/land Lot 2 – Stable Cottage, Barn & Campsite/land Lot 3 – Fell Cottage Stable Cottage is a fantastic Small Holding located in the hamlet of Marsett in Raydale which is being offered in 3 lots. Raydale is situated at the southern end of Lake Semerwater, the largest natural lake in Yorkshire, but quite undiscovered. The property itself is down a private track beyond the main village green. Raydale is a little Dale off Wensleydale. -

Grade 2 Listed Former Farmhouse, Stone Barns

GRADE 2 LISTED FORMER FARMHOUSE, STONE BARNS AND PADDOCK WITHIN THE YORKSHIRE DALES NATIONAL PARK swale farmhouse, ellerton abbey, richmond, north yorkshire, dl11 6an GRADE 2 LISTED FORMER FARMHOUSE, STONE BARNS AND PADDOCK WITHIN THE YORKSHIRE DALES NATIONAL PARK swale farmhouse, ellerton abbey, richmond, north yorkshire, dl11 6an Rare development opportunity in a soughtafter location. Situation Swale Farmhouse is well situated, lying within a soughtafter and accessible location occupying an elevated position within Swaledale. The property is approached from a private driveway to the south side of the B6260 Richmond to Reeth Road approximately 8 miles from Richmond, 3 miles from Reeth and 2 miles from Grinton. Description Swale Farmhouse is a Grade 2 listed traditional stone built farmhouse under a stone slate roof believed to date from the 18th Century with later 19th Century alterations. Formerly divided into two properties with outbuildings at both ends the property now offers considerable potential for conversion and renovation to provide a beautifully situated family home or possibly multiple dwellings (subject to obtaining the necessary planning consents). The house itself while needing full modernisation benefits from well-proportioned rooms. The house extends to just over 3,000 sq ft as shown on the floorplan with a total footprint of over 7,000 sq ft including the adjoining buildings. The property has the benefit of an adjoining grass paddock ideal for use as a pony paddock or for general enjoyment. There are lovely views from the property up and down Swaledale and opportunities such as this are extremely rare. General Information Rights of Way, Easements & Wayleaves The property is sold subject to, and with the benefit of all existing wayleaves, easements and rights of way, public and private whether specifically mentioned or not. -

7-Night Southern Yorkshire Dales Festive Self-Guided Walking Holiday

7-Night Southern Yorkshire Dales Festive Self-Guided Walking Holiday Tour Style: Self-Guided Walking Destinations: Yorkshire Dales & England Trip code: MDPXA-7 1, 2, 3 & 4 HOLIDAY OVERVIEW Enjoy a festive break in the Yorkshire Dales with the walking experts; we have all the ingredients for your perfect self-guided escape. Newfield Hall, in beautiful Malhamdale, is geared to the needs of walkers and outdoor enthusiasts. Enjoy hearty local food, detailed route notes, and an inspirational location from which to explore this beautiful national park. WHAT'S INCLUDED • High quality en-suite accommodation in our country house • Full board from dinner upon arrival to breakfast on departure day • The use of our Discovery Point to plan your walks – maps and route notes available www.hfholidays.co.uk PAGE 1 [email protected] Tel: +44(0) 20 3974 8865 HOLIDAYS HIGHLIGHTS • Use our Discovery Point, stocked with maps and walks directions, for exploring the local area • Head out on any of our walks to discover the varied landscape of the Southern Yorkshire Dales on foot • Enjoy magnificent views from impressive summits • Admire green valleys and waterfalls on riverside strolls • Marvel at the wild landscape of unbroken heather moorland and limestone pavement • Explore quaint villages and experience the warm Yorkshire hospitality at its best • Choose a relaxed pace of discovery and get some fresh air in one of England's most beautiful walking areas • Explore the Yorkshire Dales by bike • Ride on the Settle to Carlisle railway • Visit the spa town of Harrogate TRIP SUITABILITY Explore at your own pace and choose the best walk for your pace and ability. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses The development of education in the North Ridings of Yorkshire 1902 - 1939 Jennings, E. How to cite: Jennings, E. (1965) The development of education in the North Ridings of Yorkshire 1902 - 1939, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/9965/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk Abstract of M. Ed. thesis submitted by B. Jennings entitled "The Development of Education in the North Riding of Yorkshire 1902 - 1939" The aim of this work is to describe the growth of the educational system in a local authority area. The education acts, regulations of the Board and the educational theories of the period are detailed together with their effect on the national system. Local conditions of geograpliy and industry are also described in so far as they affected education in the North Riding of Yorkshire and resulted in the creation of an educational system characteristic of the area. -

Bolton Castle & Redmire Village

Follow in Turner’s footsteps to the spectacular... Bolton Castle & Redmire Village This short easy-going walk will take you to the historical Bolton Castle. You can see the castle much as Turner Castle did when he visited in July 1816 during his extensive Bolton ane tour of Yorkshire to sketch views for Whitaker’s A East L General History of the County of York series. Bolton Castle Bolton Arms Bolton Castle © Si Homfray Castle Bolton Redmire To Carperby A p e M d i a l l l L e a n Key B e Route e Mill Farm c Woodland k R Turner’s i Viewpoint v e Turner’s Bench r U Parking r e Public House Redmire Force Church Discover the landscapes that inspired one of Britain’s greatest artists Railway yorkshire.com/turner Follow in Turner’s footsteps to the spectacular... To start this Turner Trail... Bolton Castle & Redmire Village 01 From Redmire village hall, walk over the green and up the hill with the Bolton Arms on your left. Go under the railway bridge and turn This short easy-going walk will take you to the historical Bolton Castle. left onto the footpath and cross the bridge over Apedale Beck. You can see the castle much as Turner did when he visited in July 1816 Walk up the meadows passing a tree growing through the middle during his extensive tour of Yorkshire to sketch views for Whitaker’s A of an old barn to reach Castle Bolton Village. General History of the County of York series. -

Der Europäischen Gemeinschaften Nr

26 . 3 . 84 Amtsblatt der Europäischen Gemeinschaften Nr . L 82 / 67 RICHTLINIE DES RATES vom 28 . Februar 1984 betreffend das Gemeinschaftsverzeichnis der benachteiligten landwirtschaftlichen Gebiete im Sinne der Richtlinie 75 /268 / EWG ( Vereinigtes Königreich ) ( 84 / 169 / EWG ) DER RAT DER EUROPAISCHEN GEMEINSCHAFTEN — Folgende Indexzahlen über schwach ertragsfähige Böden gemäß Artikel 3 Absatz 4 Buchstabe a ) der Richtlinie 75 / 268 / EWG wurden bei der Bestimmung gestützt auf den Vertrag zur Gründung der Euro jeder der betreffenden Zonen zugrunde gelegt : über päischen Wirtschaftsgemeinschaft , 70 % liegender Anteil des Grünlandes an der landwirt schaftlichen Nutzfläche , Besatzdichte unter 1 Groß vieheinheit ( GVE ) je Hektar Futterfläche und nicht über gestützt auf die Richtlinie 75 / 268 / EWG des Rates vom 65 % des nationalen Durchschnitts liegende Pachten . 28 . April 1975 über die Landwirtschaft in Berggebieten und in bestimmten benachteiligten Gebieten ( J ), zuletzt geändert durch die Richtlinie 82 / 786 / EWG ( 2 ), insbe Die deutlich hinter dem Durchschnitt zurückbleibenden sondere auf Artikel 2 Absatz 2 , Wirtschaftsergebnisse der Betriebe im Sinne von Arti kel 3 Absatz 4 Buchstabe b ) der Richtlinie 75 / 268 / EWG wurden durch die Tatsache belegt , daß das auf Vorschlag der Kommission , Arbeitseinkommen 80 % des nationalen Durchschnitts nicht übersteigt . nach Stellungnahme des Europäischen Parlaments ( 3 ), Zur Feststellung der in Artikel 3 Absatz 4 Buchstabe c ) der Richtlinie 75 / 268 / EWG genannten geringen Bevöl in Erwägung nachstehender Gründe : kerungsdichte wurde die Tatsache zugrunde gelegt, daß die Bevölkerungsdichte unter Ausschluß der Bevölke In der Richtlinie 75 / 276 / EWG ( 4 ) werden die Gebiete rung von Städten und Industriegebieten nicht über 55 Einwohner je qkm liegt ; die entsprechenden Durch des Vereinigten Königreichs bezeichnet , die in dem schnittszahlen für das Vereinigte Königreich und die Gemeinschaftsverzeichnis der benachteiligten Gebiete Gemeinschaft liegen bei 229 beziehungsweise 163 . -

Do Your Wurst

Issue Number 444 December 2017, January 2018 From the Rector Do your wurst In the middle of November the bakery chain Greggs launched an OUR MISSION Advent Calendar. Its publicity campaign included an image depicting A community seeking to live well with God, the three wise men gathered around a crib containing a sausage roll. gathered around Jesus Christ in prayer and fellowship, It is fair to say that reaction was mixed: the social media group and committed to welcome, worship and witness. Christians on Twitter described the advert as ‘disrespectful’; the The Church Office Freedom Association (curiously one might think, given its name) Bolton Abbey, Skipton BD23 6AL called for a boycott of what it described as a ‘sick, anti-Christian 01756 710238 calendar’. On the other hand a member of the clergy commented in [email protected] The Rector a national newspaper that ‘the ability to receive (the calendar) in The Rectory, Bolton Abbey, Skipton BD23 6AL good part is a sign of grace’. 01756 710326 Personally I was mildly amused that a bakery chain was marketing [email protected] an Advent Calendar in the first place (though I was astonished at the Curate 07495 151987 price of £24). As to being offended, I couldn’t really see what the [email protected] fuss was about: I simply do not consider a parody of a nativity scene Website a threat to my faith. A few days before Greggs launched the www.boltonpriory.church advertisement, news began to emerge of the extent and violence of SUNDAY recent attacks on Coptic Christians in Egypt.