In This Issue

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hospital Services in Alberta – General Hospital (Active Treatment /Acute Care) JULY 2018

Alberta Health, Health Facilities Planning Branch For General Reference Purposes Only Hospital Services In Alberta – General Hospital (Active Treatment /Acute Care) JULY 2018 Hospital Services in Alberta – JULY 2018 General Hospital (Active Treatment / Acute Care) Auxiliary Hospital (Chronic/ Long Term Care) Alberta Health Services (AHS) New Zones: Zone 1 – South [ ] Zone 2 – Calgary [ ] Zone 3 – Central [ ] Zone 4 – Edmonton [ ] Zone 5 – North [ ] Legend: (1) Hospital Legal Name: Name appearing on M.O. #10/2011, as amended by M.O.s #10/2013, #42/2013, #33/2014, #31/2015 referencing the Consolidated Schedule of Approved Hospitals (CSAH). (2) Operator Type: Regional Health Authority (AHS) or Voluntary (VOL) (3) Operator Identity: Corporate organization name of the “hospital service operator”. (4) Sub-Acute Care (SAC): Some hospitals (highlighted) also operate a registered SAC service. Disclaimer: This list is compiled from registration information documented by the department as certified by Alberta Health Services (AHS). Facilities on the list may also provide health services or programs other than approved hospital services. This list is amended from time to time, as certified by Alberta Health Services, but may not be complete/accurate when it is read. Questions regarding specific facilities appearing on this list should be directed to Alberta Health Services. © 2018 Government of Alberta Page 1 of 24 Alberta Health, Health Facilities Planning Branch For General Reference Purposes Only Hospital Services In Alberta – General -

Banff Health Data and Summary

Alberta Health Primary Health Care - Community Profiles Community Profile: Banff Health Data and Summary Version 2, March 2015 Alberta Health, Primary Health Care March 2015 Community Profile: Banff Table of Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. i Community Profile Summary .............................................................................................................. iii Zone Level Information .......................................................................................................................... 1 Map of Alberta Health Services Calgary Zone ......................................................................................... 2 Population Health Indicators ..................................................................................................................... 3 Table 1.1 Zone versus Alberta Population Covered as at March 31, 2014 ............................................ 3 Table 1.2 Health Status Indicators for Zone versus Alberta Residents, 2012 and 2013 (BMI, Physical Activity, Smoking, Self-Perceived Mental Health) ............................................................................................... 3 Table 1.3 Zone versus Alberta Infant Mortality Rates (per 1,000 live births), Years 2011 – 2013 ................................................................................................................. 4 Local Geographic Area Level Information -

Department of Surgery Annual Report 2010/2011 April 1, 2010 to March 31, 2011

/ DEPARTMENT OF SURGERY ANNUAL REPORT 2010/2011 APRIL 1, 2010 TO MARCH 31, 2011 TOGETHER, LEADING AND CREATING EXCELLENCE IN SURGICAL CARE ANNUAL REPORT 2010/2011 Report Designed, Compiled and Edited by Matthew Hayhurst, Christine Bourgeois and Andria Marin-Stephens All Content and Photography (Unless Otherwise Stated) Provided by Matthew Hayhurst We Wish to Thank all the Surgeons, Administrators and other team members, whose tremendous efforts made this report possible. Matthew Hayhurst No Part of this Publication may be reproduced, stored in, or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the prior written permission of the copyright owners. Mailing Address: Foothills Medical Centre 1403 - 29th Street N.W. Calgary, Alberta, T2N 2T9 ph: (403) 944-1697 fax: (403) 270-8409 [email protected] Copyright © 2011 Department of Surgery/University of Calgary. All Rights Reserved Page ii ANNUAL REPORT 2010/2011 TABLE OF CONTENTS This Year in the Department Message from Dr. John Kortbeek 1 Surgical Executive Team 2 About the Department 3 From the Office of Surgical Education 5 From the Office of Surgical Research 7 From the Office of Health Technology & Innovation 9 From the Office of the Safety Officer 11 Around the Hospital Remote Ultrasound 13 Mentorship Program 14 Our Faculty Clinical Research Award, Dr. Bryan Donnelly 15 South Health Campus (2011 Update) 16 Richmond Road Otolaryngology Clinic (now in full service) -

2016 Department of Pathology & Laboratory Medicine Annual Report

Executive Summary 3 Executive Summary _____________________________________________________________________ 3 Departmental Structure and Organization 4 Governance __________________________________________________________________________ 4 Departmental Committees ________________________________________________________________ 6 Divisions, Sections and/or Programs ________________________________________________________ 7 Membership (Appendix 1.1) ______________________________________________________________ 7 Accomplishments and Highlights 8 Clinical Service (by Section) ______________________________________________________________ 8 Anatomical Pathology/Cytopathology Section (AP/Cyto) ________________________________________ 8 Clinical Biochemistry Section ______________________________________________________________ 9 General Pathology Section ______________________________________________________________ 12 Hematopathology Section _______________________________________________________________ 25 Microbiology Section __________________________________________________________________ 29 Transfusion Medicine Section ____________________________________________________________ 31 Education ___________________________________________________________________________ 33 Publications __________________________________________________________________________ 40 Research Grants ______________________________________________________________________ 42 Medical Leadership and Administration_____________________________________________________ -

AHS Calgary Zone Brochure

Hi gvie CALGARY amond amond amond ZONE Black Black ZONE Population 1.4 M CALGARY DID YOU KNOW… Life Expectancy 82.9 years Okotoks 14 new neonatal intensive care beds will rooms and will service 200,000 outpatient Hospitals 13 open at Alberta Children’s Hospital (ACH) visits and perform 2,500 births every year. by October 2013, specializing in complex L AHS is signifi cantly expanding continuing care Physicians 2,857 neonatal patients who require consults from and will add 350 beds in the Calgary Zone by multiple services at ACH. e AHS Employees 36,488 the end of 2013. e The South Health Campus will be fully Volunteers 4,263 The Foothills Medical Centre in Calgary is the Chestermer operational in late 2013 and will have 2,400 largest tertiary hospital in Canada, with more ZONE Meals Served 4.5 M per year full-time equivalent staff, approximately 180 ek y STATS… than 1,000 inpatient beds. 2 physicians, 269 inpatient beds, 11 operating Calgar Size 39,300 km or approximately fi ve times the size of P.E.I. C ALPHABETICAL LISTING OF SERVICES BY COMMUNITY • CALGARY ZONE KNOW YOUR For more information about health care options, programs and services, contact your local facility at the numbers provided below. Many programs and services, such as Addiction & Airdrie Mental Health and Public Health, are available through your local health centre. OPTIONS… AIRDRIE CHESTERMERE rane Airdrie Mental Health Clinic Chestermere Health Centre When you need health care, you have many Addiction & Mental Health 403-948-3878 Addiction & Mental Health 403-207-8773 options. -

2020 Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology Annual Report

2020 Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology Annual Report TABLE OF CONTENTS 3 Organizational Chart 62 Education Residency Program 7 Who We Are Undergraduate / Course 6 Faculty Maternal-fetal Medicine Residents Minimally Invasive Surgery Clinical Fellows Pelvic Medicine Staff Gyne-Oncology Retirement(s) Pediatric and Adolescent Continuing Medical Education 13 COVID -19 16 Division and Site Update 84 Research FMC QI/QA RGH PLC 92 World Health SHC Out of Country/ UnInsured Pelvic Medicine & Reconstructive Surg Global Health Minimally Invasive Surgery Chronic Pain 97 Digital Footprint Gynaecology Oncology Department Webpage Maternal-fetal Medicine Connect Care Fetal Therapy Reproductive Endocrine, Infertility 101 Policy Pediatric and Adolescent Gynaecology Ambulatory Care Clinics 104 The Numbers Antenatal Community Care Specialist Link Perinatal Mortality Committee DIMR Gynaecology Outpatient clinic DEAR Fund 125 Publication and Grants ORGANIZATIONAL CHART Zone Medical Director, Director, Medical Affairs Calgary Zone Jeannie Shrout Dr. Sid Viner Associate Zone Medical Director Dr. Laurie-Ann Baker Zone Clinical Department Zone Clinical Department Manager Head Scott Banks Dr. Colin Birch Division Chief Maternal-fetal Medicine Dr. Verena Kuret Site Leader Department Administrative Director of Research Director of Education Foothills Medical Centre Assistant Dr. Stephen Wood Dr. Pam Chu Dr. Simrit Brar Crystal Ryszewski Division Chief Pelvic Medicine and Reconstructive Surgery Site Leader Dr. Shunaha Kim-Fine Peter Lougheed Centre Dr. Quynh Tran Continuing Medical PGME CBD Evaluation Chair PGME Program Director Undergraduate Medical Education Dr. Sarah McQuillan Dr. Sarah Glaze Education Division Chief Dr. Weronika Harris- Dr. Michael Secter Minimally Invasive Site Leader Thompson Gynaecologic Surgery Rockyview General Hospital Course VI Dr. Chandrew Rajakumar Dr. -

Executive Summary Accreditation Report

Executive Summary Accreditation Report Alberta Health Services Accredited Alberta Health Services is accredited under the Qmentum accreditation program, Accreditation Canada provided program requirements continue to be met. We are independent, Alberta Health Services is participating in the Accreditation Canada Qmentum not-for-profit, and 100 percent accreditation program. Qmentum helps organizations strengthen their quality Canadian. For more than 55 years, improvement efforts by identifying what they are doing well and where we have set national standards improvements are needed. and shared leading practices from around the globe so we can Organizations that become accredited with Accreditation Canada do so as a continue to raise the bar for health mark of pride and as a way to create a strong and sustainable culture of quality quality. and safety. As the leader in Canadian health Accreditation Canada commends Alberta Health Services for its ongoing work care accreditation, we accredit to integrate accreditation into its operations to improve the quality and safety more than 1,100 health care and of its programs and services. social services organizations in Canada and around the world. Accreditation Canada is accredited by the International Society for Quality in Health Care (ISQua) www.isqua.org, a tangible Alberta Health Services (2017) demonstration that our programs meet international standards. Alberta Health Services (AHS) is Canada’s largest healthcare organization serving over four million Albertans. More than 104,000 skilled and dedicated Find out more about what we do health professionals, support staff, volunteers and physicians promote at www.accreditation.ca. wellness and provide healthcare every day in 450 hospitals, clinics, continuing care and mental health facilities, and community sites throughout the province. -

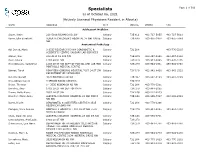

Specialists Page 1 of 509 As of October 06, 2021 (Actively Licensed Physicians Resident in Alberta)

Specialists Page 1 of 509 as of October 06, 2021 (Actively Licensed Physicians Resident in Alberta) NAME ADDRESS CITY POSTAL PHONE FAX Adolescent Medicine Soper, Katie 220-5010 RICHARD RD SW Calgary T3E 6L1 403-727-5055 403-727-5011 Vyver, Ellie Elizabeth ALBERTA CHILDREN'S HOSPITAL 28 OKI DRIVE Calgary T3B 6A8 403-955-2978 403-955-7649 NW Anatomical Pathology Abi Daoud, Marie 9-3535 RESEARCH RD NW DIAGNOSTIC & Calgary T2L 2K8 403-770-3295 SCIENTIFIC CENTRE CALGARY LAB SERVICES Alanen, Ken 242-4411 16 AVE NW Calgary T3B 0M3 403-457-1900 403-457-1904 Auer, Iwona 1403 29 ST NW Calgary T2N 2T9 403-944-8225 403-270-4135 Benediktsson, Hallgrimur 1403 29 ST NW DEPT OF PATHOL AND LAB MED Calgary T2N 2T9 403-944-1981 493-944-4748 FOOTHILLS MEDICAL CENTRE Bismar, Tarek ROKYVIEW GENERAL HOSPITAL 7007 14 ST SW Calgary T2V 1P9 403-943-8430 403-943-3333 DEPARTMENT OF PATHOLOGY Bol, Eric Gerald 4070 BOWNESS RD NW Calgary T3B 3R7 403-297-8123 403-297-3429 Box, Adrian Harold 3 SPRING RIDGE ESTATES Calgary T3Z 3M8 Brenn, Thomas 9 - 3535 RESEARCH RD NW Calgary T2L 2K8 403-770-3201 Bromley, Amy 1403 29 ST NW DEPT OF PATH Calgary T2N 2T9 403-944-5055 Brown, Holly Alexis 7007 14 ST SW Calgary T2V 1P9 403-212-8223 Brundler, Marie-Anne ALBERTA CHILDREN HOSPITAL 28 OKI DRIVE Calgary T3B 6A8 403-955-7387 403-955-2321 NW NW Bures, Nicole DIAGNOSTIC & SCIENTIFIC CENTRE 9 3535 Calgary T2L 2K8 403-770-3206 RESEARCH ROAD NW Caragea, Mara Andrea FOOTHILLS HOSPITAL 1403 29 ST NW 7576 Calgary T2N 2T9 403-944-6685 403-944-4748 MCCAIG TOWER Chan, Elaine So Ling ALBERTA CHILDREN HOSPITAL 28 OKI DR NW Calgary T3B 6A8 403-955-7761 Cota Schwarz, Ana Lucia 1403 29 ST NW Calgary T2N 2T9 DiFrancesco, Lisa Marie DEPARTMENT OF PATHOLOGY (CLS) MCCAIG Calgary T2N 2T9 403-944-4756 403-944-4748 TOWER 7TH FLOOR FOOTHILLS MEDICAL CENTRE 1403 29TH ST NW Duggan, Maire A. -

Annual Report – April 1, 2019 to March 31, 2020

The 2019-20 AHS Annual Report was prepared in accordance with the Fiscal Planning and Transparency Act, Regional Health Authorities Act, and instructions as provided by Alberta Health. The 2019-20 fiscal year spanned from April 1, 2019 to March 31, 2020. All material economic and fiscal implications known as of June 24, 2020 have been considered in preparing the Report. For more information about our programs and services, please visit www.ahs.ca or call HealthLink at 811. 2019-20 | Alberta Health Services Annual Report Table of Contents Message from the Board Chair and President & CEO .................................................................................................................... 2 Alberta Health Services Responds to COVID-19 ............................................................................................................................ 4 About Alberta Health Services ........................................................................................................................................................ 6 Map ................................................................................................................................................................................................. 9 Quick Facts ................................................................................................................................................................................... 10 Bed Numbers ............................................................................................................................................................................... -

Primary Health Care Community Profile

Alberta Health Primary Health Care - Community Profiles Community Profile: Canmore Health Data and Summary Primary Health Care Division February 2013 Alberta Health, Primary Health Care Division February 2013 Community Profile: Canmore Table of Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. i Community Profile Summary .............................................................................................................. iii Zone Level Information .......................................................................................................................... 1 Map of Alberta Health Services Calgary Zone ......................................................................................... 2 Population Health Indicators ..................................................................................................................... 3 Table 1.1 Zone versus Alberta Population Covered as at March 31, 2012 ........................................... 3 Table 1.2 Health Status Indicators for Zone versus Alberta Residents, 2010 and 2011 (BMI, Physical Activity, Smoking, Self-Perceived Mental Health) ............................................................................................... 3 Table 1.3 Zone versus Alberta Infant Mortality Rates (per 1,000 live births), Fiscal Years 2008/2009 to 2010/2011 ................................................................................... 4 Local Geographic -

Alberta Blood Cancer Resource Guide

Alberta Blood Cancer Resource Guide The Leukemia & Lymphoma Society of Canada Prairies Region #316, 1212 31 Avenue NE Calgary, AB T2E 7S8 403-263-5300 Toll-free 1.866.547.5433 (press 2 for Alberta) www.llscanada.org Updated January 2017 1 The mission of The Leukemia & Lymphoma Society of Canada is to cure leukemia, lymphoma, Hodgkin’s disease and myeloma, and improve the quality of life of patients and their families. This resource guide has been developed to make it easier for those affected by blood cancers (patients, family or other caregivers) to access a complex healthcare and social service system and find the services to match your individual situation and style. This guide is a “work in progress,” not a complete list, and your comments and suggestions are welcome. Knowing what you need and expressing those needs are the first steps in finding information and support. A cancer diagnosis can bring a sense of vulnerability and some people feel uncomfortable asking for assistance. However, you are not alone in this experience, so please let others know what you need! This includes family members, as most organizations provide services for patients and their immediate family. If during your search for services you cannot find what you need, please inform staff about the need anyway. Identifying needs is the way to raise awareness and create change. Even if a particular organization does not offer a service, staff may be able to connect you with others who are working toward the same goals. Please be an informed consumer and evaluate these services according to your own situation. -

Community Mapping – Operational Review

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Kahui Tautoko Consulting Ltd (KTCL) wishes to thank the management and staff of the participating First Nations communities including Chiefs and Council, Health Directors and their teams and the members of the First Nations community focus groups; tribal council members and other First Nations participants such as the National First Nations Health Technicians Network (NFNHTN) and members of the Non-Insured Health Benefit (NIHB) Navigators Network. We also thank and acknowledge the key stakeholders from provincial and territorial health services, private counsellors and practitioners; and Health Canada nursing personnel who participated. We acknowledge and appreciate the leadership, support and advice of the Assembly of First Nations (AFN), the First Nations and Inuit Health Branch (FNIHB) and members of the NIHB Joint Review Steering Committee (JRSC) who are undertaking this review. 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ......................................................................................................................................... 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS ............................................................................................................................................. 3 GLOSSARY ............................................................................................................................................................. 4 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .........................................................................................................................................