The Liberal Campaign in South-West Lancashire in 1868 ,.* by P

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Steve and Darlah Thomas 'WILLIAM LEIGH of NEWTON-LE-WILLOWS

Steve and Darlah Thomas ‘WILLIAM LEIGH OF NEWTON-LE-WILLOWS, CLOCKMAKER 1763-1824 : PART 1’ Antiquarian Horology, Volume 33, No. 3 (March 2012), pp. 311-334 The AHS (Antiquarian Horological Society) is a charity and learned society formed in 1953. It exists to encourage the study of all matters relating to the art and history of time measurement, to foster and disseminate original research, and to encourage the preservation of examples of the horological and allied arts. To achieve its aims the AHS holds meetings and publishes a quarterly peer-reviewed journal Antiquarian Horology. It also publishes a wide variety of scholarly books on timekeeping and its history, which are regarded as the standard and authoritative works in their field. The journal, printed to the highest standards with many colour pages, contains a variety of articles, the society’s programme, news, letters and high-quality advertising (both trade and private). A complete collection of the journals is an invaluable store of horological information, the articles covering diverse subjects including many makers from the famous to obscure. For more information visit www.ahsoc.org ANTIQUARIAN Volume 33 No. 3 (March 2012) contains 144 pages. HOROLOGY It contains the articles listed below, and is completed by the regular sections Horological News, Book NUMBER THREE VOLUME THIRTY-THREE MARCH 2012 Reviews, AHS News, Letters to the Editor and For Your Further Reading. Steve and Darlah Thomas, ‘William Leigh of Newton-le-Willows, clockmaker 1763-1824 : Part 1’ - pp. 311-334 John A. Robey, ‘A Large European Iron Chamber Clock’ - pp. 335-346 Sebastian Whitestone,’ The Chimerical English Pre-Huygens Pendulum Clock’ - pp. -

Placenamesofliverpool.Pdf

THE LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA LOS ANGELES LIVERPOOL DISTRICT PLACE-NAMES. ^Liverpool . t/tai Saxon hive.'—Matthew Arnold. ' Liverpool . the greatest covunercial city in the world' Nathaniel Hawthorne. ' That's a great city, and those are the lamps. It's Liverpool.' ' ' Christopher Tadpole (A. Smith). ' In the United Kingdom there is no city luhichfrom early days has inspired me with so -much interest, none which I zvould so gladly serve in any capacity, however humble, as the city of Liverpool.' Rev. J. E. C. Welldon. THE PLACE-NAMES OF THE LIVERPOOL DISTRICT; OR, ^he l)i0torj) mxb Jttciining oi the ^oral aiib llibev ^mncQ oi ,S0xitk-to£0t |£ancashtrc mxlb oi SEirral BY HENRY HARRISON, •respiciendum est ut discamus ex pr^terito. LONDON : ELLIOT STOCK, 62, PATERNOSTER ROW, E.G. 1898. '^0 SIR JOHN T. BRUNNER, BART., OF "DRUIDS' CROSS," WAVERTREE, MEMBER OF PARLIAMENT FOR THE NOKTHWICH DIVISION OF CHESHIRE, THIS LITTLE VOLUME IS RESPECTFULLY DEDICATED BY HIS OBEDIENT SERVANT, THE AUTHOR. 807311 CONTENTS. PACE INTRODUCTION --.--. 5 BRIEF GLOSSARY OF SOME OF THE CHIEF ENGLISH PLACE-NAME COMPONENTS - - - "17 DOMESDAY ENTRIES - - - - - 20 LINGUISTIC ABBREVIATIONS, ETC. - - - 23 LIVERPOOL ------- 24 HUNDRED OF WEST DERBY - - - "33 HUNDRED OF WIRRAL - - - - - 75 LIST OF WORKS QUOTED - - - - - lOI INTRODUCTION. This little onomasticon embodies, I believe, the first at- tempt to treat the etymology of the place-names of the Liverpool district upon a systematic basis. In various local and county histories endeavours have here and there been made to account for the origin of certain place-names, but such endeavours have unfortunately only too frequently been remarkable for anything but philological, and even topographical, accuracy. -

Ascerta Landscape, Arboricultural & Ecological Solutions for the Built Environment

Ascerta Landscape, Arboricultural & Ecological Solutions for the Built Environment Bat Survey Hermitage Green Lane, Winwick, Warrington, WA2 8SL November 2015 Revision Date Description Ascerta Mere One, Mere Grange, Elton Head Road, St Helens, Merseyside WA9 5GG T: 0845 463 4404 F: 0845 463 4405 E: [email protected] www.landscapetreesecology.com P.597.15 Bat Survey of Reeves House Hermitage Green Lane, Winwick, Warrington, WA2 8SL For Mr & Mrs Roberts 2 November 2015 Field Work by Dr Rosalind King MCIEEM and Rachael Hamilton Document Author Rachael Hamilton Technical Review Dr Rosalind King QA Review & Approval Ciaran Power Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................................................. - 1 - 1.0 Introduction ................................................................................................................ - 2 - 2.0 Objectives .................................................................................................................. - 2 - 3.0 Relevant Legislation ................................................................................................. - 3 - 4.0 Survey Method ........................................................................................................... - 4 - 4.1 Survey Methods...................................................................................................... - 4 - 4.0 Survey Method (Continued) ...................................................................................... - 5 - -

North Park Road and South Park Road Conservation Areas Management Plan (2018);

Character Appraisal January 2018 North Park Road and South Park Road Conservation Areas January 2018 Foreword The Conservation Area Appraisal should be read in junction with the following documents or their successors: North Park Road and South Park Road Conservation Areas Management Plan (2018); The National Planning Policy Framework (2012); National Planning Practice Guidance; Knowsley Local Plan: Core Strategy (2016) including saved policies from the Knowsley Unitary Development Plan (2006); Adopted Supplementary Planning Guidance. The omission of mention of any building, site or feature should not be taken to imply that it is of no interest. This document has been written and prepared by Knowsley Metropolitan Borough Council. Planning Services, Knowsley Metropolitan Borough Council, Yorkon Building, Archway Road, Huyton, Knowsley Merseyside L36 9FB Telephone: 0151 443 2380 2 NORTH PARK ROAD & SOUTH PARK ROAD CONSERVATION AREA APPRAISAL CONTENTS CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION ...................................................................... 5 1.1 North Park Road and South Park Road Conservation Areas .............................................. 5 1.2 Planning Policy Context ..................................................................................................... 6 2 LOCATION AND LANDSCAPE SETTING ............................. 7 2.1 Location and Setting .......................................................................................................... 7 2.2 Topography and Geology ................................................................................................. -

The Jazz Rag

THE JAZZ RAG ISSUE 140 SPRING 2016 EARL HINES UK £3.25 CONTENTS EARL HINES A HIGHLY IMPRESSIVE NEW COLLECTION OF THE MUSIC OF THE GREAT JAZZ PIANIST - 7 CDS AND A DVD - ON STORYVILLE RECORDS IS REVIEWED ON PAGE 30. 4 NEWS 7 UPCOMING EVENTS 8 JAZZ RAG CHARTS NEW! CDS AND BOOKS SALES CHARTS 10 BIRMINGHAM-SOLIHULL JAZZ FESTIVALS LINK UP 11 BRINGING JAZZ TO THE MILLIONS JAZZ PHOTOGRAPHS AT BIRMINGHAM'S SUPER-STATION 12 26 AND COUNTING SUBSCRIBE TO THE JAZZ RAG A NEW RECORDING OF AN ESTABLISHED SHOW THE NEXT SIX EDITIONS MAILED 14 NEW BRANCH OF THE JAZZ ARCHIVE DIRECT TO YOUR DOOR FOR ONLY NJA SOUTHEND OPENS £17.50* 16 THE 50 TOP JAZZ SINGERS? Simply send us your name. address and postcode along with your payment and we’ll commence the service from the next issue. SCOTT YANOW COURTS CONTROVERSY OTHER SUBSCRIPTION RATES: EU £20.50 USA, CANADA, AUSTRALIA £24.50 18 JAZZ FESTIVALS Cheques / Postal orders payable to BIG BEAR MUSIC 21 REVIEW SECTION Please send to: LIVE AT SOUTHPORT, CDS AND FILM JAZZ RAG SUBSCRIPTIONS PO BOX 944 | Birmingham | England 32 BEGINNING TO CD LIGHT * to any UK address THE JAZZ RAG PO BOX 944, Birmingham, B16 8UT, England UPFRONT Tel: 0121454 7020 FESTIVALS IN PERIL Fax: 0121 454 9996 Email: [email protected] In his latest Newsletter Chris Hodgkins, former head of Jazz Services, heads one item, ‘Ealing Jazz Festival under Threat’. He explains that the festival previously ran for eight Web: www.jazzrag.com days with 34 main stage concerts, then goes on: ‘Since outsourcing the management of the festival to a private contractor the Publisher / editor: Jim Simpson sponsorships have ended, admission charges have been introduced and now it is News / features: Ron Simpson proposed to cut the Festival to just two days. -

Wealthy Business Families in Glasgow and Liverpool, 1870-1930 a DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO

NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY In Trade: Wealthy Business Families in Glasgow and Liverpool, 1870-1930 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS for the degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Field of History By Emma Goldsmith EVANSTON, ILLINOIS December 2017 2 Abstract This dissertation provides an account of the richest people in Glasgow and Liverpool at the end of the nineteenth and beginning of the twentieth centuries. It focuses on those in shipping, trade, and shipbuilding, who had global interests and amassed large fortunes. It examines the transition away from family business as managers took over, family successions altered, office spaces changed, and new business trips took hold. At the same time, the family itself underwent a shift away from endogamy as young people, particularly women, rebelled against the old way of arranging marriages. This dissertation addresses questions about gentrification, suburbanization, and the decline of civic leadership. It challenges the notion that businessmen aspired to become aristocrats. It follows family businessmen through the First World War, which upset their notions of efficiency, businesslike behaviour, and free trade, to the painful interwar years. This group, once proud leaders of Liverpool and Glasgow, assimilated into the national upper-middle class. This dissertation is rooted in the family papers left behind by these families, and follows their experiences of these turbulent and eventful years. 3 Acknowledgements This work would not have been possible without the advising of Deborah Cohen. Her inexhaustible willingness to comment on my writing and improve my ideas has shaped every part of this dissertation, and I owe her many thanks. -

Eric Hobsbawm and All That Jazz RICHARD J

Eric Hobsbawm and all that jazz RICHARD J. EVANS The latest annual collection of Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the British Academy, published in December 2015, includes an extended obituary of Eric Hobsbawm (1917-2012), written by Professor Sir Richard Evans FBA. Hobsbawm was one of the UK’s most renowned modern historians and left-wing public intellectuals. His influential three-volume history of the 19th and 20th centuries, published between 1962 and 1987, put a new concept on the historiographical map: ‘the long 19th century’. The full obituary may be found via www.britishacademy.ac.uk/memoirs/14/ This extract from the obituary reveals Eric Hobsbawm’s less well-known interest in jazz. here seemed to be no problem in Eric’s combining his post at Birkbeck College [University of London] Twith his Fellowship at King’s College Cambridge, but when the latter came to an end in 1954 he moved permanently to London, occupying a large flat in Torrington Place, in Bloomsbury, close to Birkbeck, which he shared over time with a variety of Communist or ex- Communist friends. Gradually, as he emerged from the depression that followed the break-up of his marriage, he began a new lifestyle, in which the close comradeship and sense of identity he had found in the Communist movement was, above all from 1956 onwards, replaced by an increasingly intense involvement with the world of jazz. Already before the war his cousin Denis Preston had played records by Louis Armstrong, Bessie Smith and other musicians to him on a wind-up gramophone Eric Hobsbawm (1917-2012) was elected a Fellow of the British Academy in Preston’s mother’s house in Sydenham. -

Rainford Conservation Area Appraisal.Pdf

Rainford I & II Conservation Area Appraisal July 2008 Rainford I & II Conservation Area Appraisal— Rainford I & II Conservation Area Appraisal Located immediately north of St Helens town, Rainford is well known for its indus- trial past. It was the location of sand mining for the glass factories of St Helens and was a major manufacturer of clay smoking pipes, firebricks and earthenware cruci- bles. Natural resources brought fame and prosperity to the village during the late eight- eenth and early nineteenth centuries. The resulting shops, light industries and sub- sequent dwelling houses contribute to Rainford’s distinct character. In recognition of its historical significance and architectural character, a section of Rainford was originally designated as a conservation area in 1976. Rainford re- mains a ‘typical’ English country village and this review is intended to help preserve and enhance it. Rainford I & II Conservation Area Appraisal— Rainford I & II Conservation Area Appraisal Rainford I & II Conservation Area Appraisal— Rainford I & II Conservation Area Appraisal Contents Content Page 1.0 Introduction 1 2.0 Policy Context 4 3.0 Location and Setting 7 4.0 Historical Background 10 5.0 Character Area Analysis 16 6.0 Distinctive Details and Local Features 27 7.0 Extent of Loss, Intrusion and Damage 28 8.0 Community Involvement 30 9.0 Boundary Changes 31 10.0 Summary of Key Character 35 11.0 Issues 38 12.0 Next Steps 41 References 42 Rainford I & II Conservation Area Appraisal— Rainford I & II Conservation Area Appraisal Rainford I & II Conservation Area Appraisal— Rainford I & II Conservation Area Appraisal 1.0 Introduction 1.0 Introduction Rainford is a bustling linear village between Ormskirk and St Helens in Merseyside. -

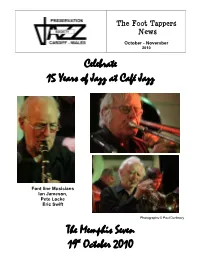

October 2010 E-Mail

The Foot Tappers News October - November 2010 Celebrate 15 Years of Jazz at Café Jazz Font line Musicians Ian Jameson, Pete Locke Eric Swift Photographs © Paul Dunleavy The Memphis Seven 19th October 2010 e-mail :- Editorial [email protected] Tel :- 029 20625639 September 2010 In October we celebrate 15 years of presentations at Café Jazz and to mark this we have some of your favourite bands plus a new band to us from London – more about them later. In those 15 years we have had the 10th Avenue Band and the Black Eagle Bands as well as Jim Beatty, Jeff Barnhart, and Jim Fryer from the USA, Mysto’s Hot Lips Band form Sweden, the late Tommy Burton, Phil Mason. Spats Langham, Roy Williams, John Barnes and numerous others from the UK as well as our great local musicians. The Adamant, Marching Band played at Brecon Cathedral to a packed congregation and then paraded to the Castle Hotel via the town with the Dean adopting the role of Parade Marshal. I assume the festival went ahead, but a walk through town showed little or no festival activity. Well done “The fringe” for providing some excellent music, personally I think that they should have the Arts Council funding as at least they tried to get back to the roots of the festival in providing music by Welsh musicians and involving the local community. A reminder for those who like to come to Café Jazz by car. You can park your car in the new St David’s Car Park, at the John Lewis Store, for £1.00. -

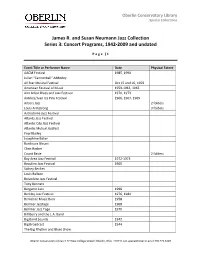

James R. and Susan Neumann Jazz Collection Series 3: Concert Programs, 1942-2009 and Undated

Oberlin Conservatory Library Special Collections James R. and Susan Neumann Jazz Collection Series 3: Concert Programs, 1942-2009 and undated P a g e | 1 Event Title or Performer Name Date Physical Extent AACM Festival 1985, 1990 Julian "Cannonball" Adderley All Star Musical Festival Oct 15 and 16, 1959 American Festival of Music 1959-1963, 1965 Ann Arbor Blues and Jazz Festival 1970, 1973 Antibes/Juan les Pins Festival 1966, 1967, 1969 Arbors Jazz 2 folders Louis Armstrong 3 folders Astrodome Jazz Festival Atlanta Jazz Festival Atlantic City Jazz Festival Atlantic Mutual Jazzfest Pearl Bailey Josephine Baker Banlieues Bleues Chris Barber Count Basie 2 folders Bay Area Jazz Festival 1972-1973 Beaulieu Jazz Festival 1960 Sidney Bechet Louis Bellson Belvedere Jazz Festival Tony Bennett Bergamo Jazz 1998 Berkley Jazz Festival 1976, 1984 Berkshire Music Barn 1958 Berliner Jazztage 1968 Berliner Jazz Tage 1970 Bill Berry and the L.A. Band Big Band Sounds 1942 Big Broadcast 1944 The Big Rhythm and Blues Show Oberlin Conservatory Library l 77 West College Street l Oberlin, Ohio 44074 l [email protected] l 440.775.5129 Oberlin Conservatory Library Special Collections James R. and Susan Neumann Jazz Collection Series 3: Concert Programs, 1942-2009 and undated P a g e | 2 The Big Show 1957, 1965 The Biggest Show of… 1951-1954 Birdland 1956 Birdland Stars of… 1955-1957 Art Blakey's Jazz Messengers Blue Note Boston Globe Jazz Festival Boston Jazz Festival Lester Bowie British Jazz Extravaganza Big Bill Broonzy Les Brown and His Band of Renown -

Annual Report Front May 15

Key Facts Gillmoss Bus Depot, East Lancashire Road, Liverpool, L11 0BB 0151 330 6200 42.42 million [email protected] passenger journeys were made on Stagecoach stagecoachbus.com Merseyside & South Lancs Buses Follow us on Twitter @stagecoachMCSL 17.81 million We aim to satisfy our customers’ queries as quickly miles operated across Merseyside and South Lancashire reason you are unhappy with the response that we provide, please contact the Bus Appeals Body on 0300 111 0001 99.3% or by writing to reliability and 94.8% The Bus Appeals Body, PO Box 119, punctuality on services throughout Merseyside & South Lancashire Shepperton, TW17 8UX For timetable information, call Traveline on 0871 200 22 33. 407 buses across Merseyside Calls cost 12p per minute plus your phone company’s access charge. Cheshire and Lancashire Annual 1197 employed across 4 Stagecoach Merseyside & South Performance Lancashire depots Merseyside & South Lancashire £13.3 million May 2015-April 2016 investment in new buses All details correct at the time of going to print, August 2016. About us Stagecoach Merseyside and South Lancashire provides local bus services in Lancashire, Merseyside, Cheshire West & Chester, Halton and parts of Greater Manchester. Our aim is to provide safe, reliable, punctual, clean and comfortable services with a good value for money range of tickets. This annual report covers the year from May 2015 to April 2016. Our team Our tickets Our key achievements All of our vehicles are inspected and serviced by our We are a major local employer in the North West of We pride ourselves on oering some of the lowest engineers at least every four weeks. -

334.04 Ribblers Lane, Kirkby

CONSERVATION AREA APPRAISAL2005 Ribblers Lane, Kirkby Location Ribblers Lane is a linear Conservation Area which runs parallel to the M57 and it has the character of a semi rural suburb and most of the buildings are listed. The area is bordered by a narrow strip of green belt and a high density housing development. History Although Ribblers Lane is currently included in the Kirkby area, historically it bears little relationship to the settlement of medieval times. The small concentration at Little Briton was one of the early centres within the Kirkby Township and lies quite close to the north-eastern edge of the Conservation Area. The significance of Ribblers Lane is that it was used as a route between Prescot and Sefton, passing through Knowsley and Aintree from the seventeenth century. On the Kirkby Tithe Award map of 1839 no buildings are shown along the current Conservation Area section of Ribblers Lane. The map does illustrate small linear plots bordering on Ribblers Lane, suggesting that building was imminent or had commenced. Indeed, on the first edition of the Ordnance Survey 1845-7, cottages were shown along the south-western side of the lane with the Sefton Arms located opposite. The area has remained predominately rural with meadowland and Willow Bed Plantation stretching towards Knowsley Brook. The Sefton Arms Inn had ceased its function as a watering hole and has been converted into residential use namely, Sefton Arms Cottages. After the Second World War the north-eastern side of Ribblers Lane was bordered by public housing, which was part of the planned movement of population from Liverpool.