Mackenzie Families of the Barony of Lochbroom

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2019 Cruise Directory

Despite the modern fashion for large floating resorts, we b 7 nights 0 2019 CRUISE DIRECTORY Highlands and Islands of Scotland Orkney and Shetland Northern Ireland and The Isle of Man Cape Wrath Scrabster SCOTLAND Kinlochbervie Wick and IRELAND HANDA ISLAND Loch a’ FLANNAN Stornoway Chàirn Bhain ISLES LEWIS Lochinver SUMMER ISLES NORTH SHIANT ISLES ST KILDA Tarbert SEA Ullapool HARRIS Loch Ewe Loch Broom BERNERAY Trotternish Inverewe ATLANTIC NORTH Peninsula Inner Gairloch OCEAN UIST North INVERGORDON Minch Sound Lochmaddy Uig Shieldaig BENBECULA Dunvegan RAASAY INVERNESS SKYE Portree Loch Carron Loch Harport Kyle of Plockton SOUTH Lochalsh UIST Lochboisdale Loch Coruisk Little Minch Loch Hourn ERISKAY CANNA Armadale BARRA RUM Inverie Castlebay Sound of VATERSAY Sleat SCOTLAND PABBAY EIGG MINGULAY MUCK Fort William BARRA HEAD Sea of the Glenmore Loch Linnhe Hebrides Kilchoan Bay Salen CARNA Ballachulish COLL Sound Loch Sunart Tobermory Loch à Choire TIREE ULVA of Mull MULL ISLE OF ERISKA LUNGA Craignure Dunsta!nage STAFFA OBAN IONA KERRERA Firth of Lorn Craobh Haven Inveraray Ardfern Strachur Crarae Loch Goil COLONSAY Crinan Loch Loch Long Tayvallich Rhu LochStriven Fyne Holy Loch JURA GREENOCK Loch na Mile Tarbert Portavadie GLASGOW ISLAY Rothesay BUTE Largs GIGHA GREAT CUMBRAE Port Ellen Lochranza LITTLE CUMBRAE Brodick HOLY Troon ISLE ARRAN Campbeltown Firth of Clyde RATHLIN ISLAND SANDA ISLAND AILSA Ballycastle CRAIG North Channel NORTHERN Larne IRELAND Bangor ENGLAND BELFAST Strangford Lough IRISH SEA ISLE OF MAN EIRE Peel Douglas ORKNEY and Muckle Flugga UNST SHETLAND Baltasound YELL Burravoe Lunna Voe WHALSAY SHETLAND Lerwick Scalloway BRESSAY Grutness FAIR ISLE ATLANTIC OCEAN WESTRAY SANDAY STRONSAY ORKNEY Kirkwall Stromness Scapa Flow HOY Lyness SOUTH RONALDSAY NORTH SEA Pentland Firth STROMA Scrabster Caithness Wick Welcome to the 2019 Hebridean Princess Cruise Directory Unlike most cruise companies, Hebridean operates just one very small and special ship – Hebridean Princess. -

Achbeag, Cullicudden, Balblair, Dingwall IV7

Achbeag, Cullicudden, Balblair, Dingwall Achbeag, Outside The property is approached over a tarmacadam Cullicudden, Balblair, driveway providing parking for multiple vehicles Dingwall IV7 8LL and giving access to the integral double garage. Surrounding the property, the garden is laid A detached, flexible family home in a mainly to level lawn bordered by mature shrubs popular Black Isle village with fabulous and trees and features a garden pond, with a wide range of specimen planting, a wraparound views over Cromarty Firth and Ben gravelled terrace, patio area and raised decked Wyvis terrace, all ideal for entertaining and al fresco dining, the whole enjoying far-reaching views Culbokie 5 miles, A9 5 miles, Dingwall 10.5 miles, over surrounding countryside. Inverness 17 miles, Inverness Airport 24 miles Location Storm porch | Reception hall | Drawing room Cullicudden is situated on the Black Isle at Sitting/dining room | Office | Kitchen/breakfast the edge of the Cromarty Firth and offers room with utility area | Cloakroom | Principal spectacular views across the firth with its bedroom with en suite shower room | Additional numerous sightings of seals and dolphins to bedroom with en suite bathroom | 3 Further Ben Wyvis which dominates the skyline. The bedrooms | Family shower room | Viewing nearby village of Culbokie has a bar, restaurant, terrace | Double garage | EPC Rating E post office and grocery store. The Black Isle has a number of well regarded restaurants providing local produce. Market shopping can The property be found in Dingwall while more extensive Achbeag provides over 2,200 sq. ft. of light- shopping and leisure facilities can be found in filled flexible accommodation arranged over the Highland Capital of Inverness, including two floors. -

BGS Report, Single Column Layout

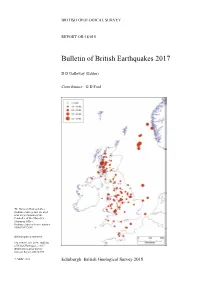

BRITISH GEOLOGICAL SURVEY REPORT OR/18/015 Bulletin of British Earthquakes 2017 D D Galloway (Editor) Contributors: G D Ford The National Grid and other Ordnance Survey data are used with the permission of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office. Ordnance Survey licence number 100017897/2005 Bibliographical reference GALLOWAY, D D 2018. Bulletin of British Earthquakes 2017. British Geological Survey Internal Report, OR/18/015 © NERC 2018 Edinburgh British Geological Survey 2018 BRITISH GEOLOGICAL SURVEY The full range of Survey publications is available from the BGS Keyworth, Nottingham NG12 5GG Sales Desks at Nottingham and Edinburgh; see contact details 0115-936 3241 Fax 0115-936 3488 below or shop online at www.thebgs.co.uk e-mail: [email protected] The London Information Office maintains a reference collection of www.bgs.ac.uk BGS publications including maps for consultation. Shop online at: www.thebgs.co.uk The Survey publishes an annual catalogue of its maps and other publications; this catalogue is available from any of the BGS Sales Lyell Centre, Research Avenue South, Edinburgh EH14 4AP Desks. 0131-667 1000 Fax 0131-668 2683 The British Geological Survey carries out the geological survey of e-mail: [email protected] Great Britain and Northern Ireland (the latter as an agency service for the government of Northern Ireland), and of the surrounding London Information Office at the Natural History Museum continental shelf, as well as its basic research projects. It also (Earth Galleries), Exhibition Road, South Kensington, London undertakes programmes of British technical aid in geology in SW7 2DE developing countries as arranged by the Department for International Development and other agencies. -

Local Amenities

Local Amenities Name Image Type Location Services Hours of opening / Contact no Tourist Tourist West Informtn Winter – closed Information informatio Argyle on Spring/Autumn Centre n Street activities 9:30 – 16:30 Ullapool and Summer accomdtn bookings 9:00 – 17:30 Sundays 10:00 – 16:00 08452 255121 Ullapool Weekly Shops and Essential Fridays 35p News news, Newsagent for What’s Newsagents and views and outlets On grocer shops and what’s on Office Lochbroom Market St Hardware Ullapool 01854 613334 editorial@theullap oolnews.co.uk Lochbroom Swimming, Quay Court Weekday Leisure & fitness Street games, 12:00-22:00 Ullaspool room and Ullapool family fun, Weekend sports keep fit 10:00 to 18:00 activities 01854 612884 Name Image Type Address / Services Hours of opening Location and contact number Ullapool Museum West Shop Closed till March. Museum Artifacts Argyle History Then see Ullapool Heritage Street Genealogy News. Genealogy Ullapool Natural Access by History appointment 01854 612987 Golf Course Driving Morefield Golf Club See Tourist pitch. North Road House information office for Course Ullapool details 9 holes Tel : 01854 613323 01854 613323 Disc Golf Disc Golf Bull Park Course and See Tourist office for Course End of Camp baskets lay details site out West Terrace Summer Summer Ullapool Wild life and Departures Queen Islands Pier local history Monday to Saturday Boat Trips Cruise Booking talks 10:00 – (4hrs) 4hrs Booth 14:15 – (2hrs) Sunday Isle Martin 11:00 (3hrs) Cruise 2hrs 14:15 (2hrs) 01854 612472 Isle Martin Open days Depart on Boat trip to See Ullapool News Day Excursion during the Summer Island. -

Cabar Feidh the Canadian Chapter Magazine

Clan MacKenzie Society in the Americas Cabar Feidh The Canadian Chapter Magazine September 2003 ISSN 1207-7232 and of Seaforth’s vassals during his exile in France is abridged from an interesting and valuable work. It brings out in a promi- In This Issue: nent light the state of the Highlands and the futility of the power of the Government during that period in the North. As regards History of the Mackenzies - Part 14. 1 - 3 several of the forfeited estates which lay in inaccessible situations Pedigrees of the Early Chiefs - Part 2 . 3 - 5 in the Highlands, the commissioners had up to this time been Book Reviews . 5 entirely baffled, never having been able even to get them sur- Obituary - John R. MacKenzie . 6 veyed. This was so in a very special manner in the case of the Sarah Ann MacKenzie Duff 1857 - 1887 . 6 immense territory of the Earl of Seaforth, extending from Brahan James Mackenzie and the Mackenzie Country . 8 - 9 Castle, near Dingwall in the east, across to Kintail in the west, as The Freeman’s Advocate & James Mackenzie . 9 -10 well as in the large island of the Lewis. The districts of Lochalsh and Kintail, on the west coast, the scene of the Spanish invasion The Mackenzie trip to Nova Scotia . .11 - 12, 19 of 1719, were peculiarly difficult of access, there being no Letters . 12 approach from the south, east, or north, except by narrow and dif- Fairburn Tower in Danger of Collapse . 13 ficult paths, while the western access was only assailable by a Printing Family Trees . -

2018/19 Area Structures Progress Report

Agenda 6 item Report RC/016/19 no THE HIGHLAND COUNCIL Committee: Ross and Cromarty Committee Date: 1 May 2019 Report Title: 2018/19 Area Structures Progress Report Report By: Director of Community Services 1 Purpose/Executive Summary 1.1 This report provides an update on the work undertaken on the Area Structures Programme for 2018/19 financial year. 2 Recommendations 2.1 Members are asked to note the contents of the report. 3 Structures Assets 3.1 In Ross and Cromarty there are 361 bridges, 89 culverts and 199 retaining walls that are on adopted roads. 4 Finance 4.1 Structures maintenance and repairs are funded from Ross and Cromarty’s Area Revenue Budget. The 2018/19 structures budget was set at £117,200. At the end of February 2019 £170,045, or 145%, of the budget has been spent. 5 Bridge Inspection Programme 5.1 All bridges receive General and Principal Inspections. General Inspections are undertaken on a risk based inspection cycle of either two or three years as approved at the November 2018 EDI Committee. The risk based inspection intervals are dependent on condition, exposure and risk of deterioration as set out in the guidance issued by the Society of Chief Officers of Transportation in Scotland. Principal Inspections are undertaken at 6, 9, or 12 year intervals. An inspection programme for all other structures such as retaining walls is being prepared based on a three yearly cycle of inspections. This inspection programme will be implemented in phases from 2019/20. 5.2 Bridge General Inspections are undertaken by Area staff. -

Eastpark House, Badralloch, Dundonnell, Garve, Ross-Shire Offers Around £280,000

Eastpark House, Badralloch, Dundonnell, Garve, Ross-Shire Offers Around £280,000 Eastpark House, Property Description Our View Located within the popular scattered community of A unique opportunity to purchase an Eco Home that Badralloch, Dundonnell, Badralloch, this Makar built ecological designed house offers a peaceful lifestyle. offers flexible accommodation over two floors. With Garve, Ross-Shire amazing views this property offers a Highland home for those seeking solitude while being well placed for Location access to the Highland Capital City of Inverness. Primary Located on the Scoraig Peninsula, this unique property Schooling is available at Badcaul while secondary is at Offers Around £280,000 is well placed for access to the scenically beautiful West Ullapool. EPC = Highlands of Scotland. The area offers a wide range of outdoor activities and many places of outstanding natural beauty are within easy access. Inverness is approx 60 miles distant and offers all city facilities to include links by road, rail and air to further destinations. ** UNDER OFFER ** For full EPC please contact the branch IMPORTANT NOTE TO PURCHASERS: We endeavour to make our sales particulars accurate and reliable, however, they do not constitute or form part of an offer or any contract and none is to be relied upon as statements of representation or fact. The services, systems and appliances listed in this specification have not been tested by us and no guarantee as to their operating ability or efficiency is given. All measurements have been taken as guide to prospective buyers only, and are not precise. Floor plans where included are not to scale and accuracy is not guaranteed. -

Growing Our Future

OFFICIAL Growing Our Future Draft Community Food Growing Strategy September 2020 -2025 Highland Council September 2020 OFFICIAL Contents Page 1. Introduction.……………………………………………………………………………………………...3 2. Aim of strategy………………..…………………………………………………………………………5 3. Resilient Communities…………………………………………………………………………………7 4. Culture Change………………………………………………………………………………………….8 5. Who was involved in developing this strategy?………………………………………………….10 6. Community Growing in the Highlands…………………………………………….……………….12 7. Available Support………………………………………………………………………………………18 8. Action Plan………………………………………………………………………………………………23 Appendices Stakeholders Involved with shaping strategy…………………………………………………………29 Case Studies…………………………………………………………………………………………………30 A National Strategic Context……………………………………………………………………………..49 Consultation Questions …………………………………………………………………………………...50 2 1. Introduction The Community Empowerment (Scotland) Act 2015 aims to help empower communities across Scotland and improve access to land for those wanting to grow their own food. The Highland Council recognises the wide ranging benefits of community growing and through this strategy seeks to inspire, promote and support community growing across the Highlands. The benefits of growing your own (GYO) are endless, from improved mental health to reduced carbon footprints and saving money to meeting new friends. Food is one thing that unites us all and improving our relationship with food can be transformative. Health Those involved in growing their own food eat more vegetables and this has -

Strategic Transport Projects Review Report 1 – Review of Current and Future Network Performance

Transport Scotland Strategic Transport Projects Review Report 1 – Review of Current and Future Network Performance 7.2 Corridor 2: Inverness to Ullapool and Western Isles 7.2.1 Setting the Context Corridor 2 extends north and west from Inverness to northwest Scotland and includes onward connections to the Western Isles (Eilean Siar), as shown in Figure 7.2.1. It connects the city of Inverness with Ullapool, which are approximately 92 kilometres apart. Ullapool has an onward ferry connection to Stornoway. The population of the corridor (excluding Eilean Siar) is approximately 16,000 and little change is forecast over the period to 2022333. In contrast, the population of Eilean Siar is forecast to decline over this period by almost 15 per cent334. However the largest change in population overall, shown in Figure 7.2.2, is in and around Inverness. It is expected that there will be employment growth of approximately four per cent in the Highland council area as a whole, but a decline of similar magnitude in Eilean Siar335. Areas of greatest change are shown in Figure 7.2.2. The national level of car ownership, measured as a percentage of households with access to a car, is 67 per cent. Within the corridor, car ownership levels are above average, as expected, due to the rural nature of the corridor: • Highland council area: 75 per cent; and • Eilean Siar: 70 per cent336. The economic inactivity rate within the Highlands and Eilean Siar was around 16 per cent in 2005. This is slightly below the Scottish average of 21 per cent337. -

Standard Word Document Template

Ross and Cromarty Expedition Area information Useful information from the Expedition Network Welcome! Green forms and requests for assessment should be submitted to the Scottish Network Co-ordinator, who can also assist with enquiries regarding routes and campsites Eleanor Birch DofE Scotland Rosebery House 9 Haymarket Terrace Edinburgh EH12 5EZ T: 0131 343 0920 E: [email protected] Eleanor works 9-5 Monday, Tuesday and Thursday. Contents Contents ........................................................................................................................................ 1 Introduction .................................................................................................................................... 2 Area boundaries ............................................................................................................................ 2 Maps of the area ............................................................................................................................ 3 Route updates ............................................................................................................................... 3 Campsites ...................................................................................................................................... 4 Travel and transport to the area .................................................................................................... 5 Hazards ........................................................................................................................................ -

SOILS in EASTER ROSS 1. the Black Isle (Part O F Sheets 83, 84, 93 and 94) 2. Cromarty and Invergordon (Sheet 94) TECHNICAL REPO

SOILS IN EASTER ROSS 1. The Black Isle (part of Sheets 83, 84, 93 and 94) 2. Cromarty and Invergordon (Sheet 94) TECHNICAL REPORT NO. 1 The Macaulay Institute for Soil Research, Crai giebuckler, ABERDEEN AB9 2QJ Scotland Tel: 0224 38611 Preface The two reports covering soils in Easter Ross are edited versions of general accounts, written by J.C.C. Romans, which appeared in the Macaulay Institute for Soil Research Annual Reports Nos. 38 TL first deals .w.fth AL- aiid 40. Lrie area covered by the Biack isle soil map (Parts of Sheets 83, 84, 93 and 94) and the second the area covered by the Cromarty and Invergordon soil map (Sheet 94). A bulletin describing the soils of the Black Isle will be pub1 i shed 1 ater this year. The Macaulay Institute for Soil Research, Aberdeen. July 1984 1. THE BLACK ISLE (part of Sheets 83, 84, 93 and 94) -rL - ne Biack Isle fs a narrow peninsuia in Easter ROSS about 20 miles long lying between the Cromarty Firth and the Moray Firth. Its western boundary is taken to be the road between the Inverness district boundary and Conon Bridge. It has an area of about 280 square kilometres with a width of 7 or 8 miles in the broadest part, narrowing to 4 miles near Rosemarkie, and to less than 2 miles near Cromarty. When viewed from the hills on the north side of the Crornarty Firth the Black Isle stands out long, low and smooth in outline, with a broad central spine rising to over 240 metres at the summit of Mount Eagle. -

Title Page Reva

Aultbea to Dundonnell 33kV Overhead Distribution Line Upgrade Environmental Statement Volume 1 Written Statement December 2009 By: For: AULTBEA TO DUNDONNELL 33kV DISTRIBUTION LINE UPGRADE ENVIRONMENTAL STATEMENT DECEMBER 2009 ash design+assessment 21 Gordon Street Glasgow G1 3PL Tel: 0141227 3388 Fax: 0141 227 3399 email: [email protected] www.ashdesignassessment.co Scottish and Southern Energy Aultbea to Dundonnell 33kV Distribution Line Upgrade Environmental Statement PREFACE Scottish Hydro Electric Power Distribution Plc (SHEPD) are proposing to replace the existing 11,000 volt wood pole overhead distribution network between Aultbea and Dundonnell. The existing overhead line is 58km including the existing spurs and provides electricity to 344 customers. It is one of the last remaining cadmium copper overhead line circuits on the exposed west coast of Scotland and is considered to be a high priority for major refurbishment due to unacceptable physical condition and poor system performance. The majority of the overhead line was built in 1950 to a light duty, long span specification using 3/.093 (.017sq in) cadmium copper conductors. The circuit is three phase (three wire) for the first few kilometres from Aultbea to Laide and part way along the Opinan 11,000 volt spur. The remainder of the circuit is single phase (two wire). The original line was extended from Dundonnell Forest to Eilean Darroch in 1956 and then on to Dundonnell House in 1958. These sections of line incorporate shorter span lengths and use 3/.104 (.025sq in) copper conductors. The circuit has suffered 20 faults over the last 5 years. The majority of faults on this circuit relate to age, deterioration and under-design.