Fleecer Mountains Watersheds Based on Information Developed by a 10 Person Interdisciplinary Team

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

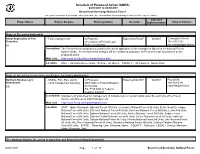

Schedule of Proposed Action (SOPA)

Schedule of Proposed Action (SOPA) 04/01/2007 to 06/30/2007 Beaverhead-Deerlodge National Forest This report contains the best available information at the time of publication. Questions may be directed to the Project Contact. Expected Project Name Project Purpose Planning Status Decision Implementation Project Contact Projects Occurring Nationwide Aerial Application of Fire - Fuels management In Progress: Expected:07/2007 08/2007 Christopher Wehrli Retardant 215 Comment Period Legal 202-205-1332 EA Notice 07/28/2006 fire [email protected] Description: The Forest Service proposes to continue the aerial application of fire retardant to fight fires on National Forest System lands. An environmental analysis will be conducted to prepare an Environmental Assessment on the proposed action. Web Link: http://www.fs.fed.us/fire/retardant/index.html. Location: UNIT - All Districts-level Units. STATE - All States. COUNTY - All Counties. Nation Wide. Projects Occurring in more than one Region (excluding Nationwide) Northern Rockies Lynx - Wildlife, Fish, Rare plants In Progress: Expected:04/2007 04/2007 Ray Smith Amendment - Land management planning DEIS NOA in Federal Register 406-329-3381 EIS 01/16/2004 [email protected] Est. FEIS NOA in Federal Register 04/2007 Description: Management guidelines for management of Canada Lynx on certain lands under the authority of the Forest Service and Bureau of Land Management Web Link: http://www.fs.fed.us/r1/planning/lynx.html Location: UNIT - Idaho Panhandle National Forest All Units, Clearwater National -

Inland Habitat Associations of Marbled Murrelets in British Columbia

Chapter 16 Inland Habitat Associations of Marbled Murrelets in British Columbia Alan E. Burger1 Abstract: Most Marbled Murrelets (Brachyramphus marmoratus) the greatest threat (Rodway 1990, Rodway and others in British Columbia nest in the Coastal Western Hemlock 1992). The listing stimulated several inland studies, biogeoclimatic zone. In this zone, detection frequencies were highest including reconnaissance surveys in many watersheds of in the moister ecosections and in low elevation forests. Nests and the Queen Charlotte Islands (Rodway and others 1991, moderately high levels of activity were also found in some forest 1993a) and Vancouver Island (Savard and Lemon in press) patches in the subalpine Mountain Hemlock zone. There was no evidence of nesting in subalpine scrub forest, lowland bog forest, and intensive surveys at several sites. or alpine tundra. Studies on the Queen Charlotte Islands and Identification and mapping of potential nesting habitats Vancouver Island reported consistently higher detection frequen- was identified as a high priority for research in the National cies in old-growth than second growth forests (20-120 years old). Recovery Plan for the Marbled Murrelet, prepared by the Detections in second-growth were usually associated with nearby Canadian Marbled Murrelet Recovery Team (Kaiser and patches of old-growth. Within low elevation old-growth, detection others 1994). Detailed 1:50,000 maps of coastal old-growth frequencies were sometimes positively correlated with mean tree forests are being prepared (Derocher, pers. comm.). There diameter, but showed weak or no associations with tree species are still very few data available for either landscape- or composition and minor variations in forest structure. -

Southwest MONTANA Visitvisit Southwest MONTANA

visit SouthWest MONTANA visitvisit SouthWest MONTANA 2016 OFFICIAL REGIONAL TRAVEL GUIDE SOUTHWESTMT.COM • 800-879-1159 Powwow (Lisa Wareham) Sawtooth Lake (Chuck Haney) Pronghorn Antelope (Donnie Sexton) Bannack State Park (Donnie Sexton) SouthWest MONTANABetween Yellowstone National Park and Glacier National Park lies a landscape that encapsulates the best of what Montana’s about. Here, breathtaking crags pierce the bluest sky you’ve ever seen. Vast flocks of trumpeter swans splash down on the emerald waters of high mountain lakes. Quiet ghost towns beckon you back into history. Lively communities buzz with the welcoming vibe and creative energy of today’s frontier. Whether your passion is snowboarding or golfing, microbrews or monster trout, you’ll find endless riches in Southwest Montana. You’ll also find gems of places to enjoy a hearty meal or rest your head — from friendly roadside diners to lavish Western resorts. We look forward to sharing this Rexford Yaak Eureka Westby GLACIER Whitetail Babb Sweetgrass Four Flaxville NATIONAL Opheim Buttes Fortine Polebridge Sunburst Turner remarkable place with you. Trego St. Mary PARK Loring Whitewater Peerless Scobey Plentywood Lake Cut Bank Troy Apgar McDonald Browning Chinook Medicine Lake Libby West Glacier Columbia Shelby Falls Coram Rudyard Martin City Chester Froid Whitefish East Glacier Galata Havre Fort Hinsdale Saint Hungry Saco Lustre Horse Park Valier Box Belknap Marie Elder Dodson Vandalia Kalispell Essex Agency Heart Butte Malta Culbertson Kila Dupuyer Wolf Marion Bigfork Flathead River Glasgow Nashua Poplar Heron Big Sandy Point Somers Conrad Bainville Noxon Lakeside Rollins Bynum Brady Proctor Swan Lake Fort Fairview Trout Dayton Virgelle Peck Creek Elmo Fort Benton Loma Thompson Big Arm Choteau Landusky Zortman Sidney Falls Hot Springs Polson Lambert Crane CONTENTS Condon Fairfield Great Haugan Ronan Vaughn Plains Falls Savage De Borgia Charlo Augusta Winifred Bloomfield St. -

MAP SHOWING LOCATIONS of MINES and PROSPECTS in the DILLON Lox 2° QUADRANGLE, IDAHO and MONTANA

DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY MAP SHOWING LOCATIONS OF MINES AND PROSPECTS IN THE DILLON lox 2° QUADRANGLE, IDAHO AND MONTANA By JeffreyS. Loen and Robert C. Pearson Pamphlet to accompany Miscellaneous Investigations Series Map I-1803-C Table !.--Recorded and estimated production of base and precious metals in mining districts and areas in the Dillon 1°x2° guadrangle, Idaho and Montana [Production of other commodities are listed in footnotes. All monetary values are given in dollars at time of production. Dashes indicate no information available. Numbers in parentheses are estimates by the authors or by those cited as sources of data in list that follows table 2. <,less than; s.t., short tons] District/area Years Ore Gold Silver Copper Lead Zinc Value Sources name (s. t.) (oz) (oz) (lb) (lb) (lb) (dollars) of data Idaho Carmen Creek 18 70's-190 1 (50,000) 141, 226 district 1902-1980 (unknown) Total (50,000) Eldorado 1870's-1911 17,500 (350 ,000) 123, 226 district 1912-1954 (13,000) (8,000) (300,000) Total (650,000) Eureka district 1880's-1956 (13 ,500) 12,366 (2,680,000) 57,994 (4,000) ( 4,000 ,000) 173 Total (4,000,000) Gibbonsville 1877-1893 (unknown) district 1894-1907 (83,500) (1,670,000) 123, 226 1908-1980 ( <10 ,000) 123 Total (2,000,000) Kirtley Creek 1870's-1890 2,000 40,500 173 district 1890's-1909 (<10,000) 1910-1918 24,300 (500 ,000) 123 1919-1931 (unknown) 1932-1947 2,146 (75 ,000) 173 Total (620,000) McDevitt district 1800's.-1980 (80,000) Total (80,000) North Fork area 1800's-1980 (unknown) Total ( <10 ,000) Pratt Creek 1870's-1900 (50 ,000) district Total (50,000) Sandy Creek 1800 's-1900 (unknown) district 1901-1954 19,613 4,055 4,433 71,359 166,179 (310,000) 17 3, 200 Total (310 ,000) Montana Anaconda Range 1880's-1980 (<100,000) area Total (<100,000) Argenta district 1864-1901 (1 ,500 ,000) 1902-1965 311,796 72,241 562,159 604,135 18,189,939 2,009,366 5,522,962 88 Total (7,000,000) Baldy Mtn. -

Private Residences Big Sky | Billings | Bozeman | Livingston Winter 2020-2021

PRIVATE RESIDENCES BIG SKY | BILLINGS | BOZEMAN | LIVINGSTON WINTER 2020-2021 Big Sky Billings Bozeman Livingston 406.924.7050 406.206.0192 406.404.1960 406.946.0097 BIG SKY | BILLINGS | BOZEMAN | LIVINGSTON MONTANA Please enjoy this complimentary edition of our Residences Book, Winter 2020 Edition. Engel & Völkers is proud to represent the finest real estate in Southwestern Montana. Land, new builds, ranches, and investment properties can all be found with our excellent Advisors. We strive to achieve the best for both our buyers and sellers. From Big Sky, Billings, Bozeman, Livingston, and our Ranch partners, we welcome you to Engel & Völkers! Eric & Stacy Ossorio - Big Sky | Brokers Shawna Morales - Billings | Broker PollyAnna Snyder - Bozeman & Livingston | Broker PROPERTY INDEX BIG SKY 4 BILLINGS 19 BOZEMAN 27 LIVINGSTON 40 RANCHES & RECREATION 48 © 2020 Engel & Völkers. All rights reserved. Engel & Völkers and its independent franchisees are Equal Opportunity Employers and fully support the principles of the Fair Housing Act. Each property shop is independently owned and operated. All information provided is deemed reliable but is not guaranteed and should be independently verified. If your property is currently represented by a real estate broker, this is not an attempt to solicit your listing. Want to grow your business and become an advertising partner? Contact us today! 406.404.1960 | [email protected] WELCOME TO BIG SKY Offering “The Biggest Skiing in America”, Big Sky The nearby Gallatin River is a favorite for whitewater includes the communities of Moonlight Basin, Spanish rafters and kayakers and is a Blue Ribbon trout stream Peaks Mountain Club, Yellowstone Club, as well as attracting fly-fishers from around the world. -

Rockhounding & Geology

ttoo CrCranbrook,ranbrookk, BCBC ttoo RReeggina,ina, SKSK ttoo Cardston,Cardston, AABB ttoo AAssssiniboia,iniboia, SKSK to Lethbethbrethbridge,ridge, AABB toto KildeeKildeerr,, SSKK CANACA NADDAA to Swiwifft Current,Current, SKSK ReRexfordxforrrdd CANA DADA D EurekaEurekka WWeesstbytby N YYaaaakk , GLACIEGLACIER SSweetgrasweetgrass WhitetailWhitetail BBabbabb FoFourur una una, ND OpheimOpheim ButtesButtes t Fortinee NANATIONATIONAL Turnerurner or BLACKFEETBLAB CKFEET SunburstSSunburstt ort PARK FlaxvilleF F Tregregoo SStt. MMaarryy INDIANINDIAN PePeerleserlesl s Scobeyy PlentywooPlentywood WWhitewatehitewater to F PPoollebridgebridge Loring Lake RESERVATIONRESERVATION AApgapgararr McMcDonalDonald CUT BANKBANKNK BrBrowningowningn CHINOOCHINOOK FORTORT PPECKECCK Medicine Lakkee TrTroyoy COLUMBIAO A WeWestst GlacieGlacier SHELBYSHELBS Y IINDIANNDIAN RRESERVATIOESERVATION FALLSLSS CoraCoramC m RuRudyardyard LibbyLibby CChestehester FrFroioidd WHITEFISHWHITEFISH Martina Citytyy HAVRHAVRE Hinsdale D FoFoorrtt SaSaintaia nt D I HungrHunnggry EaEastst GGalataalata Saco N , BoBoxx LustrLustre t GlaGlacieacieciecierr BeBelknalknap MaMariariear e VVaalilieerr , nt Horse i KALISPELLKALISPELLLLL EssEEssexex PPaarrkk ElderEldere Agennccyy DoDodsonodson VaVandaliandalia MALMAM LTATA BBainvillainville CulbertsoCulbeertsort n ston i KKilaila Hearteartart Butte FORTFORTR BEBELKNALKNK AP i illiston, ND DupDupuyepuyer ill WOLFWOLF PoPoplaplarp r andpo RROCKYOCKY BBOY’OY’S INDIANINNDIIAN NNaNashuashuas W Marionn W S S POINPOINT HeronHeron SSomersomers BigforkBig -

The 1898 Field Season of CD Walcott

Field work and fossils in southwestern Montana: the 1898 field season of C. D. Walcott Ellis L. Yochelson Research Associate, Department of Paleobiology, National Museum of Natural History, Washington, DC 20013-7012 G. Zieg Senior Geologist, Teck Cominco American Inc., East 15918 Euclid, Spokane, WA 99216 INTRODUCTION In 1879, Charles Doolittle Walcott (1850- 1927) (Yochelson, 1998) joined the new U. S. Geological Survey (USGS) and July 1, 1894, became the third director of the agency. Shortly before that time the USGS had several field parties starting to investigate mining dis- tricts in Montana and Idaho. There was no overall stratigraphic succession, nor clear cor- relation from one mining district to another. In 1895, Walcott took a first quick trip through the Belt Mountains. In the vicinity of Neihart, Montana, he collected Middle Cambrian fossils (Weed, 1900). These fossils established that Lower Cambrian rocks were absent from the area and thus the Belt strata (or Algonkian, as USGS Walcott called them) were pre-Cambrian in age The unhyphenated usage and the lack of capi- ABSTRACT talization of “formation” are relatively late de- velopments in stratigraphic nomenclature. The diary of Charles Doolittle Walcott pro- vides a brief daily account of his investigations For more than fifty years, Walcott used a small of Cambrian and Precambrian rocks, mainly in pocket diary and with his comments one can the Belt Mountains during one field season. trace his route and gain some notion of how These entries also give some notion of the tri- field work was conducted before the days of als of field work before the development of the rapid automobile transportation. -

Licensed Gambling Operators 9-30-2020

9/30/2020 PROVIDED BY THE MONTANA DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE, GAMBLING CONTROL DIVISION LICENSED GAMBLING OPERATORS and LICENSEES for FISCAL YEAR 2021 GROUPED BY COUNTY, CITY AND FINALLY BY LOCATION NAME. COUNTY: BEAVERHEAD CITY: DILLON 4040442-004-GOA 15 Licensed Machine(s) BLACKTAIL STATION 26 S MONTANA ST DILLON MT 59725 Licensee: BLACKTAIL STATION INC 4065304-003-GOA 2 Licensed Machine(s) CLUB BAR 134 N MONTANA ST DILLON MT 59725 Licensee: CLUB BAR 6429929-004-GOA 5 Licensed Machine(s) GATEWAY CANYON TRAVEL PLAZA 4055 REBICH LN DILLON MT 59725 Licensee: GATEWAY CANYON TRAVEL PLAZA INC. 6665116-003-GOA 9 Licensed Machine(s) GOLDEN BAR & CASINO 8 N MONTANA ST DILLON MT 59725 Licensee: GOLDEN BAR & CASINO, LLC 6329932-002-GOA 11 Licensed Machine(s) KLONDIKE INN 33 E BANNACK ST DILLON MT 59725 Licensee: CKI, LLC 6460969-004-GOA 5 Licensed Machine(s) KNOTTY PINE TAVERN 17 E BANNACK ST DILLON MT 59725 Licensee: B & R ENTERPRISES LLC 4091300-008-GOA 20 Licensed Machine(s) LUCKY LIL'S CASINO OF DILLON 635 N MONTANA ST DILLON MT 59725 Licensee: DILLON CASINO INC 4145194-013-GOA 20 Licensed Machine(s) MAGIC DIAMOND CASINO OF DILLON 101 E HELENA ST DILLON MT 59725 Licensee: TOWN PUMP OF HARLOWTOWN INC WEB-MT_mr011 Page 1 of 191 9/30/2020 PROVIDED BY THE MONTANA DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE, GAMBLING CONTROL DIVISION LICENSED GAMBLING OPERATORS and LICENSEES for FISCAL YEAR 2021 GROUPED BY COUNTY, CITY AND FINALLY BY LOCATION NAME. COUNTY: BEAVERHEAD CITY: DILLON 6718975-003-GOA 4 Licensed Machine(s) OFFICE BAR 21 E BANNACK ST DILLON MT 59725 Licensee: ZTIK -

GM 69 Stine Mtn 24K-Jan2018-2.Ai

MONTANA BUREAU OF MINES AND GEOLOGY Geologic Map 69; Plate 1 of 1 A Department of Montana Tech of The University of Montana Geologic Map of the Stine Mountain 7.5' Quadrangle, 2017 CORRELATION DIAGRAM INTRODUCTION _glq Quartzite of Grace Lake (Cambrian?)—White to light gray, fine- to medium-grained Kg Granite of Stine Creek (Late Cretaceous)—Medium-grained, gray biotite 113° 07' 30" 5' 2' 30" R 11 W 113° 00' _glq Kg 45° 45' 45° 45' quartzite. Contains coarse intervals with rounded quartzite pebbles and angular grains of granite. Contains rare muscovite and rare secondary epidote and anhedral sphene. Qta 25 A collaborative Montana Bureau of Mines and Geology–Idaho Geological Survey quartzite, quartz, and feldspar. Lacks the pink and red quartzite and brick-red chert clasts Small body near Grouse Lakes is granodiorite containing hornblende, biotite, and Qal Qta Qpa Holocene Qaf Qls Quaternary (MBMG-IGS) mapping project began in 2007 to resolve some long-standing Ybl euhedral sphene. Kto Qg Qao Qg of the Black Lion Formation (unit ). Grains are subrounded to subangular, and Ysw Pleistocene controversies concerning the relationship between two dissimilar, immensely thick, moderately to well sorted, although coarse intervals are poorly sorted. Contains abundant Qao 10 15 Mesoproterozoic sedimentary sequences: the Lemhi Group and the Belt Supergroup well-rounded quartz grains. In hand sample, the fine-grained intervals appear KgpKgp Porphyritic biotite granite of Osborne Creek (Late Cretaceous)—Very coarse, Kgp Qta ? Pliocene (Ruppel, 1975; Winston and others, 1999; Evans and Green, 2003; O’Neill and others, feldspar-poor, but slabbed and stained samples contained 15–25 percent K-spar, and porphyritic, biotite granite. -

Precipitation Transition Regions Over the Southern Canadian Cordillera During January–April 2010 and Under a Pseudo-Global-Warming Assumption

Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci., 23, 3665–3682, 2019 https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-23-3665-2019 © Author(s) 2019. This work is distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. Precipitation transition regions over the southern Canadian Cordillera during January–April 2010 and under a pseudo-global-warming assumption Juris D. Almonte1,a and Ronald E. Stewart1 1Department of Environment and Geography, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, Manitoba, R3T 2N2, Canada anow at: Environmental Science and Engineering Program, University of Northern British Columbia, Prince George, British Columbia, V2N 4Z9, Canada Correspondence: Juris D. Almonte ([email protected]) Received: 31 January 2019 – Discussion started: 7 February 2019 Accepted: 7 August 2019 – Published: 12 September 2019 Abstract. The occurrence of various types of winter pre- During the cold season, precipitation can be solid (snow), cipitation is an important issue over the southern Canadian liquid (rain and freezing rain) or mixed (wet snow for exam- Cordillera. This issue is examined from January to April ple). The precipitation type transition region, where mixed of 2010 by exploiting the high-resolution Weather Research or freezing precipitation occurs, lies between areas of all rain and Forecasting (WRF) model Version 3.4.1 dataset that was and all snow if they both occur. Midlatitudes regions, partic- used to simulate both a historical reanalysis-driven (control ularly over many mountains, have frequent transition region – CTRL) and a pseudo-global-warming (PGW) experiment occurrences during the cold season, as the 0 ◦C isotherm can (Liu et al., 2016). Transition regions, consisting of both liq- be situated anywhere along the mountainside. -

Earthquake Hazards in the Pacific Northwest of the United States

UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Earthquake Hazards in the Pacific Northwest of the United States Compiled by A. M. Rogers TJ. Walsh WJ. Kockelman G.R. Priest EVALUATION OF LIQUEFACTION POTENTIAL, SEATTLE, WASHINGTON BvW. PAUL GRANT, 1 WILLIAM J. PERKINS,"! ANDT. LESLIE Youo2 Open-File Report 91-441-T This report was prepared under contract to (a grant from) the U.S. Geological Survey and has not been reviewed for conformity with U.S. Geological Survey editorial standards (or with the North American Stratigraphic Code). Any use of trade, product or firm names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. 1 Shannon & Wilson, Inc., 400 N. 34th Street, Seattle, Washington 2 Department of Civil Engineering, Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah 1992 Foreword This paper is one of a series dealing with earthquake hazards of the Pacific Northwest, primarily in western Oregon and western Washington. This research represents the efforts of U.S. Geological Survey, university, and industry scientists in response to the Survey initiatives under the National Earthquake Hazards Reduction Program. Subject to Director's approval, these papers will appear collectively as U.S. Geological Survey Professional Paper 1560, tentatively titled "Assessing Earthquake Hazards and Reducing Risk in the Pacific Northwest." The U.S. Geological Survey Open-File series will serve as a preprint for the Professional Paper chapters that the editors and authors believe require early release. A single Open-File will also be published that includes only the abstracts of those papers not included in the pre-release. -

THE FRASER GLACIATION in the CASCADE MOUNTAINS, SOUTHWESTERN BRITISH COLUMBIA by Betsy Anne Waddington B.Sc

THE FRASER GLACIATION IN THE CASCADE MOUNTAINS, SOUTHWESTERN BRITISH COLUMBIA By Betsy Anne Waddington B.Sc (Geology), The University, of British Columbia (1986) A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES DEPARTMENT. OF GEOGRAPHY We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA April 1995 © Betsy Anne Waddington, 1995 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the head of my department or by his or her representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of Oeog^pWy The University of British Columbia Vancouver, Canada Date f\m\\ Qt-i. Ici cl< DE-6 (2/88) ABSTRACT The objective of this study is to reconstruct the history of glaciation from the start of Fraser (Late Wisconsinan) Glaciation to the end of deglaciation, for three areas in the Cascade Mountains. The Cascade Mountains are located between the Coast Mountains and the Interior Plateau in southwestern British Columbia. The Coast Mountains were glaciated by mountain glaciation followed by frontal retreat, whereas the Interior Plateau underwent ice sheet glaciation followed by downwasting and stagnation. The Cascades were supposed to have undergone a style of glaciation transitional between these two.