Signature Characteristics in the Piano Music of John Adams Eoin Conway

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Doctor Atomic

What to Expect from doctor atomic Opera has alwayS dealt with larger-than-life Emotions and scenarios. But in recent decades, composers have used the power of THE WORK DOCTOR ATOMIC opera to investigate society and ethical responsibility on a grander scale. Music by John Adams With one of the first American operas of the 21st century, composer John Adams took up just such an investigation. His Doctor Atomic explores a Libretto by Peter Sellars, adapted from original sources momentous episode in modern history: the invention and detonation of First performed on October 1, 2005, the first atomic bomb. The opera centers on Dr. J. Robert Oppenheimer, in San Francisco the brilliant physicist who oversaw the Manhattan Project, the govern- ment project to develop atomic weaponry. Scientists and soldiers were New PRODUCTION secretly stationed in Los Alamos, New Mexico, for the duration of World Alan Gilbert, Conductor War II; Doctor Atomic focuses on the days and hours leading up to the first Penny Woolcock, Production test of the bomb on July 16, 1945. In his memoir Hallelujah Junction, the American composer writes, “The Julian Crouch, Set Designer manipulation of the atom, the unleashing of that formerly inaccessible Catherine Zuber, Costume Designer source of densely concentrated energy, was the great mythological tale Brian MacDevitt, Lighting Designer of our time.” As with all mythological tales, this one has a complex and Andrew Dawson, Choreographer fascinating hero at its center. Not just a scientist, Oppenheimer was a Leo Warner and Mark Grimmer for Fifty supremely cultured man of literature, music, and art. He was conflicted Nine Productions, Video Designers about his creation and exquisitely aware of the potential for devastation Mark Grey, Sound Designer he had a hand in designing. -

Alternately Known As 1313; Originally Releases 1977 by UZ, 1977 by Atem, Numerous Intervening Reissues, 1990 by Cuneiform

UNIVERS ZERO UNIVERS ZERO CUNEIFORM 2008 REISSUE W BONUS TRACKS & REMASTER (alternately known as 1313; originally releases 1977 by UZ, 1977 by Atem, numerous intervening reissues, 1990 by Cuneiform) Cuneiform 2008 album features: Michel Berckmans [bassoon], Daniel Denis [percussion], Marcel Dufrane [violin], Christian Genet [bass], Patrick Hanappier [violin, viola, pocket cello], Emmanuel Nicaise [harmonium, spinet], Roger Trigaux [guitar], and Guy Segers [bass, vocal, noise effects] “ALBUM OF THE WEEK...Released in 1977, it was astonishing then: today, it sounds like the hidden source for every one of today's avant-garde rock bands. Chillingly beautiful, driven by the bassoon and cello more than the guitar and synth, each instrumental is both pastoral and burgeoning with terrible life. … This is edgy beyond belief. …Each piece magnificently refuses to deviate from its mood, its tense, thrilling, growling, restrained focus... The whole is like the rare, delicious bits of great film soundtrack that create menace and energy out of nowhere. … Univers Zero are a revelation …” – Sean O., Organ, #274, September 18th, 2008 “UZ's debut remains both benchmark and landmark. Reissued numerous times over the years…this definitive version finally presents this unprecedented music the way it was meant to be heard, clarifying how—emerging out of nowhere with little history to precede it— UZ has been so vital in changing the way chamber music is perceived. UZ's music was an antecedent for the kind of instrumental and stylistic interspersion considered normal today by groups including Bang on a Can and Alarm Will Sound. Henry Cow's complex, abstruse writing meets Bartok, Stravinsky, Messiaen and Ligeti, but with hints of early music, especially in UZ's use of spinet and harmonium. -

2020-2021 BNY Mellon Grand Classics Renewal Brochure

SE THE 2020-2021 SEASON! A ASON O BENEFITS F FIRSTS! FLEXIBLE TICKET PRIORITY SEATING DISTRICT DISCOUNTS RENEW A new piano, 10 artist debuts, significant EXCHANGE Season ticket holders have priority Pittsburgh Symphony subscribers TODAY! Pittsburgh firsts, world premieres, PSO Exchange your subscription tickets over the general public on all receive a discount to select premieres and new musical voices. for any other concert within the seating within the BNY Mellon Pittsburgh Ballet, Pittsburgh CLO, 2020-2021 BNY Mellon Grand Grand Classics season. Pittsburgh Cultural Trust, Pittsburgh Classics season. Season ticket Opera and Pittsburgh Public CLICK OUTSTANDING holders can make exchanges up EXCLUSIVE PRE-SALE Theater events, as well as discounts PittsburghSymphony.org/Renew STARS OF to one hour prior to the concert. OPPORTUNITIES to local restaurants. THE STAGE Ticket exchanges made online are As a ticket holder, you will receive exclusive pre-sale opportunities to RESERVED PARKING Performances by Emanuel free of fees. special concerts before the general Season ticket holders have the first CALL Ax, Rudolf Buchbinder, DEDICATED public on-sale date. opportunity to purchase pre-paid +HLQ]+DOO%R[2IƓFH Thibaudet Hélène Grimaud, Gil Shaham, th PATRON SERVICES guaranteed parking in the 6 and 412.392.4900 Christian Tetzlaff, Matthias REPRESENTATIVE GREAT SAVINGS Penn garage across the street from Toll-free: 800.743.8560 Goerne, Jean-Yves Thibaudet, Each season ticket holder has Save on the concerts within your Heinz Hall for just $12 per concert. Yefim Bronfman, and Yo-Yo Ma! a designated Patron Services season ticket package. Plus, save After the renewal deadline parking Representative (PSR) to personally 15% on additional ticket purchases prices increase to $15. -

Cds by Composer/Performer

CPCC MUSIC LIBRARY COMPACT DISCS Updated May 2007 Abercrombie, John (Furs on Ice and 9 other selections) guitar, bass, & synthesizer 1033 Academy for Ancient Music Berlin Works of Telemann, Blavet Geminiani 1226 Adams, John Short Ride, Chairman Dances, Harmonium (Andriessen) 876, 876A Adventures of Baron Munchausen (music composed and conducted by Michael Kamen) 1244 Adderley, Cannonball Somethin’ Else (Autumn Leaves; Love For Sale; Somethin’ Else; One for Daddy-O; Dancing in the Dark; Alison’s Uncle 1538 Aebersold, Jamey: Favorite Standards (vol 22) 1279 pt. 1 Aebersold, Jamey: Favorite Standards (vol 22) 1279 pt. 2 Aebersold, Jamey: Gettin’ It Together (vol 21) 1272 pt. 1 Aebersold, Jamey: Gettin’ It Together (vol 21) 1272 pt. 2 Aebersold, Jamey: Jazz Improvisation (vol 1) 1270 Aebersold, Jamey: Major and Minor (vol 24) 1281 pt. 1 Aebersold, Jamey: Major and Minor (vol 24) 1281 pt. 2 Aebersold, Jamey: One Dozen Standards (vol 23) 1280 pt. 1 Aebersold, Jamey: One Dozen Standards (vol 23) 1280 pt. 2 Aebersold, Jamey: The II-V7-1 Progression (vol 3) 1271 Aerosmith Get a Grip 1402 Airs d’Operettes Misc. arias (Barbara Hendricks; Philharmonia Orch./Foster) 928 Airwaves: Heritage of America Band, U.S. Air Force/Captain Larry H. Lang, cond. 1698 Albeniz, Echoes of Spain: Suite Espanola, Op.47 and misc. pieces (John Williams, guitar) 962 Albinoni, Tomaso (also Pachelbel, Vivaldi, Bach, Purcell) 1212 Albinoni, Tomaso Adagio in G Minor (also Pachelbel: Canon; Zipoli: Elevazione for Cello, Oboe; Gluck: Dance of the Furies, Dance of the Blessed Spirits, Interlude; Boyce: Symphony No. 4 in F Major; Purcell: The Indian Queen- Trumpet Overture)(Consort of London; R,Clark) 1569 Albinoni, Tomaso Concerto Pour 2 Trompettes in C; Concerto in C (Lionel Andre, trumpet) (also works by Tartini; Vivaldi; Maurice André, trumpet) 1520 Alderete, Ignacio: Harpe indienne et orgue 1019 Aloft: Heritage of America Band (United States Air Force/Captain Larry H. -

Program Notes: Inspiration & Impact

CABRILLO FESTIVAL Program Notes: Inspiration & Impact Lola Montez Does the and she glides from the stage of sensory and expressive overload. Spider Dance (2016) overwhelmed with applause, At its premiere in March of 2012, the first third and smashed spiders, John Adams of the piece was largely a trope on the Opus (b. 1947) and radiant with parti-colored skirts, [World Premiere] 131 C# minor quartet’s scherzo and suffered smiles, graces, cobwebs and glory. from just this problem. After a moody opening of tremolo strings and fragments of the Ninth Commissioned by the musicians of the Cabrillo Lola Montez Does the Spider Dance was Symphony signal octave-dropping motive, Festival Orchestra in honor of Marin Alsop commissioned by members of the Cabrillo Festival Orchestra in celebration of Marin the solo quartet emerged as if out of a haze, The Irish-born actress and dancer Eliza Gilbert Alsop’s twenty five seasons as music director, playing the driving foursquare figures of that (1821—1861) achieved international fame and it is dedicated to her. scherzo material that almost immediately went under the name “Lola Montez, the Spanish through a series of strange permutations. Dancer.” After a controversial career on the —John Adams continent, including a sojourn in Bavaria This original opening never satisfied me. The where she become both the lover as well as clarity of the solo quartet’s role was often political advisor to King Ludwig, she returned Absolute Jest (2011) buried beneath the orchestral activity resulting in what sounded to me too much like “chatter.” to London, where she eloped with and married John Adams (b. -

Mahler 5 & Music You Know

CONCERT PROGRAM Friday, January 22, 2016, 10:30am Saturday, January 23, 2016, 8:00pm David Robertson, conductor Timothy McAllister, saxophone JOHN ADAMS Saxophone Concerto (2013) (b. 1947) Animato; Moderato; Tranquillo, suave Molto vivo (a hard driving pulse) Timothy McAllister, saxophone INTERMISSION MAHLER Symphony No. 5 in C-sharp minor (1901-02) (1860-1911) PART I Trauermarsch. In gemessenem Schritt. Streng. Wie ein Kondukt Stürmisch bewegt, mit größter Vehemenz PART II Scherzo. Kräftig, nicht zu schnell PART III Adagietto. Sehr langsam— Rondo-Finale. Allegro 23 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS These concerts are part of the Wells Fargo Advisors Orchestral series. These concerts are presented by St. Louis College of Pharmacy. David Robertson is the Beofor Music Director and Conductor. Timothy McAllister is the Ann and Paul Lux Guest Artist. The concert of Saturday, January 23, is underwritten in part by a generous gift from Rex and Jeanne Sinquefield. The concert of Friday, January 22, 10:30am, features coffee and doughnuts provided through the generosity of Community Coffee and Krispy Kreme, respectively. Pre-Concert Conversations are sponsored by Washington University Physicians. Large print program notes are available through the generosity of Bellefontaine Cemetery and Arboretum and are located at the Customer Service table in the foyer. 24 ON EDGE BY EDDIE SILVA Their music is made of the worlds around them, Gustav Mahler and John Adams. Mahler of that thrilling age, the shift from the 19th to the 20th century, the speed of the modern beginning to TIMELINKS change how people think and act. Also a time of anxiety, especially for a Jewish artist in an anti- Semitic Vienna. -

Joana Carneiro Music Director

JOANA CARNEIRO MUSIC DIRECTOR Berkeley Symphony 17/18 Season 5 Message from the Music Director 7 Message from the Board President 9 Message from the Executive Director 11 Board of Directors & Advisory Council 12 Orchestra 15 Season Sponsors 16 Berkeley Sound Composer Fellows & Full@BAMPFA 18 Berkeley Symphony 17/18 Calendar 21 Tonight’s Program 23 Program Notes 37 About Music Director Joana Carneiro 39 Guest Artists & Composers 43 About Berkeley Symphony 44 Music in the Schools 47 Berkeley Symphony Legacy Society 49 Annual Membership Support 58 Broadcast Dates 61 Contact 62 Advertiser Index Media Sponsor Gertrude Allen • Annette Campbell-White & Ruedi Naumann-Etienne Official Wine Margaret Dorfman • Ann & Gordon Getty • Jill Grossman Sponsor Kathleen G. Henschel & John Dewes • Edith Jackson & Thomas W. Richardson Sarah Coade Mandell & Peter Mandell • Tricia Swift S. Shariq Yosufzai & Brian James Presentation bouquets are graciously provided by Jutta’s Flowers, the official florist of Berkeley Symphony. Berkeley Symphony is a member of the League of American Orchestras and the Association of California Symphony Orchestras. No photographs or recordings of any part of tonight’s performance may be made without the written consent of the management of Berkeley Symphony. Program subject to change. October 5 & 6, 2017 3 4 October 5 & 6, 2017 Message from the Music Director Dear Friends, Happy New Season 17/18! I am delighted to be back in Berkeley after more than a year. There are three beautiful reasons for photo by Rodrigo de Souza my hiatus. I am so grateful for all the support I received from the Berkeley Symphony musicians, members of the Board and Advisory Council, the staff, and from all of you throughout this special period of my family’s life. -

Download Booklet

Acknowledgments This recording was made at the I would also like to thank the Teresa This disc is dedicated to all the Academy of Arts and Letters in Sterne Foundation, Gilbert Kalish, members of my family — especially Manhattan, New York on May and Norma Hurlburt for their gener- my mom, dad, Eve, Henry, and 26-28, 2007. Thank you to osity, which helped to make this my nephews — who have been a Ardith Holmgrain for her help disc a reality. And, a thank you to constant source of love and support in arranging our use of this Lehman College and its Shuster in my life; to my primary teachers magnificent recording space. Grant through the Research Jesslyn Kitts, Michael Zenge, Foundation of the City of New Leonard Hokanson, and Gilbert I would like to thank Max Wilcox, York for their help in the Kalish; to a cherished circle of who very graciously helped to completion of this disc. friends, which grows wider all the prepare and record this disc. time; and, to God who orchestrated Without his help it never could I would also like to thank Jeremy all of these parts. have happened. I also thank Mary Geffen, Ara Guzelemian, Kathy Schwendeman for the use of her Schumann, John Adams, Peter glorious Steinway. Thank you to Sellars, David Robertson, Dawn David Merrill who continuously Upshaw and the Carnegie Hall Publishers: t h r e a d s offered a bright smile and encour- family for giving me so many Andriessen: Boosey & Hawkes aging words during the engineering wonderfully rich treasures in my Music Publishers Limited and recording of this disc and musical experiences thus far. -

The Pulitzer Prizes 2020 Winne

WINNERS AND FINALISTS 1917 TO PRESENT TABLE OF CONTENTS Excerpts from the Plan of Award ..............................................................2 PULITZER PRIZES IN JOURNALISM Public Service ...........................................................................................6 Reporting ...............................................................................................24 Local Reporting .....................................................................................27 Local Reporting, Edition Time ..............................................................32 Local General or Spot News Reporting ..................................................33 General News Reporting ........................................................................36 Spot News Reporting ............................................................................38 Breaking News Reporting .....................................................................39 Local Reporting, No Edition Time .......................................................45 Local Investigative or Specialized Reporting .........................................47 Investigative Reporting ..........................................................................50 Explanatory Journalism .........................................................................61 Explanatory Reporting ...........................................................................64 Specialized Reporting .............................................................................70 -

THE CLEVELAN ORCHESTRA California Masterwor S

����������������������� �������������� ��������������������������������������������� ������������������������ �������������������������������������� �������� ������������������������������� ��������������������������� ��������������������������������������������������� �������������������� ������������������������������������������������������� �������������������������� ��������������������������������������������� ������������������������ ������������������������������������������������� ���������������������������� ����������������������������� ����� ������������������������������������������������ ���������������� ���������������������������������������� ��������������������������� ���������������������������������������� ��������� ������������������������������������� ���������� ��������������� ������������� ������ ������������� ��������� ������������� ������������������ ��������������� ����������� �������������������������������� ����������������� ����� �������� �������������� ��������� ���������������������� Welcome to the Cleveland Museum of Art The Cleveland Orchestra’s performances in the museum California Masterworks – Program 1 in May 2011 were a milestone event and, according to the Gartner Auditorium, The Cleveland Museum of Art Plain Dealer, among the year’s “high notes” in classical Wednesday evening, May 1, 2013, at 7:30 p.m. music. We are delighted to once again welcome The James Feddeck, conductor Cleveland Orchestra to the Cleveland Museum of Art as this groundbreaking collaboration between two of HENRY COWELL Sinfonietta -

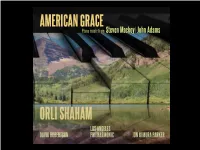

ORLI SHAHAM LOS ANGELES DAVID ROBERTSON PHILHARMONIC JON KIMURA PARKER 1 Merican Composers Have Always Pushed Boundaries, As Americans Themselves Have a Pushed West

AMERICAN GRACE Piano music from Steven Mackey | John Adams ORLI SHAHAM LOS ANGELES DAVID ROBERTSON PHILHARMONIC JON KIMURA PARKER 1 merican composers have always pushed boundaries, as Americans themselves have A pushed West. I feel strongly that John Adams and Steven Mackey are at the forefront of defining what it means to be an American pianist today. On a stunning summer’s day in 2007 in the inspiring Rocky Mountain valley of Aspen, I found myself as usual underground, in a windowless practice room. One of the magical things about Aspen is that the otherwise oppressive quality of such a room is transformed by the people who inhabit it. I was taking a practice break from Gershwin and Stravinsky, preparing for rehearsal with the orchestra, when Steve Mackey came off the stage from rehearsing his guitar concerto Tuck and Roll. I was seven months pregnant with my twin sons, and Steve and I immediately started to talk about both music and child-bearing, which his wife was soon to do as well. I relished our talk and was further enthralled by Steve’s sizzling guitar playing and magnetic compositional style. For the next months, I ravenously listened to his oeuvre, convincing me that he was the first composer I wanted to ask to write me a concerto. The process was amazing. Steve showed me bits now and again, listened to my recordings and live performances, asked about my hand size, even allowed me a say in the final dramatic turn of the piece. Every time a part of the score came my way, I was more excited to learn it and understand it. -

Form in the Music of John Adams

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2018 Form in the Music of John Adams Michael Ridderbusch Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Recommended Citation Ridderbusch, Michael, "Form in the Music of John Adams" (2018). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 6503. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/6503 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Form in the Music of John Adams Michael Ridderbusch DMA Research Paper submitted to the College of Creative Arts at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in Music Theory and Composition Andrew Kohn, Ph.D., Chair Travis D. Stimeling, Ph.D. Melissa Bingmann, Ph.D. Cynthia Anderson, MM Matthew Heap, Ph.D. School of Music Morgantown, West Virginia 2017 Keywords: John Adams, Minimalism, Phrygian Gates, Century Rolls, Son of Chamber Symphony, Formalism, Disunity, Moment Form, Block Form Copyright ©2017 by Michael Ridderbusch ABSTRACT Form in the Music of John Adams Michael Ridderbusch The American composer John Adams, born in 1947, has composed a large body of work that has attracted the attention of many performers and legions of listeners.