Hypnotherapy for Traumatic Grief: Janetian and Modern Approaches Integrated

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Read Book Hypnotism and Mesmerism Ebook, Epub

HYPNOTISM AND MESMERISM PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Thomas Jay Hudson | 30 pages | 10 Sep 2010 | Kessinger Publishing | 9781168649201 | English | Whitefish MT, United States Hypnotism and Mesmerism PDF Book Mesites and Roatelos Mesitornithidae. The controversy between official medical science and Mesmerism raged bitterly. Out of these, the cookies that are categorized as necessary are stored on your browser as they are essential for the working of basic functionalities of the website. HOAD " mesmerism. Thought-reading and clairvoyance as transcendental faculties were rejected. Later on, instead of mesmerism, he created the word "nervous hypnosis" and invented a hypnotic introduction method called gaze method. Phreno- mesmerism , or the connexion between phrenology and mesmerism. Mystery solved. The same study found the physical and mental experiences during mesmerism were also different than during hypnosis. Mesoamerican Religions: Mythic Themes. Eighty four percent of the subjects felt mesmerism was a deeper trance than hypnosis. A profound silence was observed, broken only by strains of music which occasionally floated through the rooms. More From Entertainment. In modern times, a treatment method called hypnotherapy has been established. He became a celebrity, going on tour and giving dramatic demonstrations of his techniques and powers at the courts of the European nobility. Finding traditional tactics unsuccessful, Mesmer followed the suggestion of Jesuit priest and astronomer Maximilian Hell, who attached magnets to his patients to treat disease. Professional clairvoyants arose. To that end, they acknowledged that the power of suggestion on the imagination could have therapeutic value. However, just as Mesmer was right for the wrong reasons, so his critics were wrong for the right reasons, and failed to draw the correct conclusions from their observations. -

Hypnotherapy.Pdf

Hypnotherapy An Exploratory Casebook by Milton H. Erickson and Ernest L. Rossi With a Foreword by Sidney Rosen IRVINGTON PUBLISHERS, Inc., New York Halsted Press Division of JOHN WILEY Sons, Inc. New York London Toronto Sydney The following copyrighted material is reprinted by permission: Erickson, M. H. Concerning the nature and character of post-hypnotic behavior. Journal of General Psychology, 1941, 24, 95-133 (with E. M. Erickson). Copyright © 1941. Erickson, M. H. Hypnotic psychotherapy. Medical Clinics of North America, New York Number, 1948, 571-584. Copyright © 1948. Erickson, M. H. Naturalistic techniques of hypnosis. American Journal of Clinical Hypnosis, 1958, 1, 3-8. Copyright © 1958. Erickson, M. H. Further clinical techniques of hypnosis: utilization techniques. American Journal of Clinical Hypnosis, 1959, 2, 3-21. Copyright © 1959. Erickson, M. H. An introduction to the study and application of hypnosis for pain control. In J. Lassner (Ed.), Hypnosis and Psychosomatic Medicine: Proceedings of the International Congress for Hypnosis and Psychosomatic Medicine. Springer Verlag, 1967. Reprinted in English and French in the Journal of the College of General Practice of Canada, 1967, and in French in Cahiers d' Anesthesiologie, 1966, 14, 189-202. Copyright © 1966, 1967. Copyright © 1979 by Ernest L. Rossi, PhD All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner whatever, including information storage or retrieval, in whole or in part (except for brief quotations in critical articles or reviews), without written permission from the publisher. For information, write to Irvington Publishers, Inc., 551 Fifth Avenue, New York, New York 10017. Distributed by HALSTED PRESS A division of JOHN WILEY SONS, Inc., New York Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Erickson, Milton H. -

Hypnotherapy Academy Catalog.Pdf

Celebrating 33 Years of Unparalleled Preparation For Certification in Hypnotherapy HypnotherapyHypnotherapy AcademyAcademy ofof AmericaAmerica State Licensed Hypnotherapy Course Exclusive Providers of Integral Hypnotherapy™ Training 2021 Course Catalog The Study of Hypnosis Provides You “At the Academy I With an Understanding of regained my The Very Nature of Human Miracles self-respect and The acceptance of hypnotherapy by the You will notice that our professional self-confidence, and conventional medical and psychological certification training is far more in-depth than the now experience community as a powerful tool for healing is the others. We designed it this way because we take new leading edge in patient care. Hospitals, clinics your investment of time, tuition, travel and effort self-acceptance, and mental health centers around the world are seriously — our students tell us it’s paying off. exploring how to make use of these “integrative” Graduates from this program have phenomenal self-understanding and and “complementary” therapies, and they all need results with their clients, and so they command self-forgiveness. I made highly trained and competent hypnotherapists to a fee of $125 to $275, on average, for private do that. The National Institutes of Health (NIH), sessions and up to $250 for a personalized friends and learned the American Medical Association (AMA), and the hypnosis recording. how to accept others as American Psychological Association (APA), among others, have recognized the validity of the mind- To study hypnosis is to understand the very they are. I discovered my body connection. nature of human miracles. Whether you’re leaving purpose. an old career that doesn’t reflect who you are The Hypnotherapy Academy of America and you want to open your own hypnotherapy Thanks to your love and is gratified to be part of creating this new era practice, or you want to integrate clinical hypnosis teachings Tim, hypnotherapy is enjoying. -

Hypnotherapy

WHOLE HEALTH: INFORMATION FOR VETERANS Hypnotherapy Whole Health is an approach to health care that empowers and enables YOU to take charge of your health and well-being and live your life to the fullest. It starts with YOU. It is fueled by the power of knowing yourself and what will really work for you in your life. Once you have some ideas about this, your team can help you with the skills, support, and follow up you need to reach your goals. All resources provided in these handouts are reviewed by VHA clinicians and Veterans. No endorsement of any specific products is intended. Best wishes! https://www.va.gov/wholehealth/ Hypnotherapy Hypnotherapy What is hypnotherapy? Hypnotherapy, or clinical hypnosis, can improve your health by helping you relax and focus your mind.1 Someone trained in this powerful mind-body approach can help you go into a more focused state of mind (called a “hypnotic state”) so you can learn more about yourself, improve your health, and change your habits and thought patterns. How does hypnosis work? Hypnosis can work in several ways:2 • It can draw on your ability to use your imagination to bring about helpful or healthy changes. • The hypnotherapist can offer a therapeutic idea or suggestion while you are in a relaxed and focused state. In this state of focused attention, the effect of the idea or suggestion on your mind is more powerful. That means that you are more likely to take the helpful idea seriously and act on it in the future. This can help you reach your goals faster in your daily life.2 For example, if the hypnotherapist offers the suggestion that you can stop smoking during hypnosis, this may improve your chances of being able to stop. -

Hypnotherapy: Fact Or Fiction: a Review in Palliative Care and Opinions of Health Professionals

[Downloaded free from http://www.jpalliativecare.com on Sunday, October 23, 2011, IP: 190.156.172.218] || Click here to download free Android application for this journal Original Article Hypnotherapy: Fact or Fiction: A Review in Palliative Care and Opinions of Health Professionals Geetha Desai, Santosh K Chaturvedi, Srinivasa Ramachandra Department of Psychiatry, Nimhans, Bengaluru, India Address for correspondence: Dr. Geetha Desai; E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT Context: Complementary medicine like hypnotherapy is often used for pain and palliative care. Health professionals vary in views about hypnotherapy, its utility, value, and attitudes. Aims: To understand the opinions of health professionals on hypnotherapy. Settings and Design: A semi-qualitative method to survey opinions of the health professionals from various disciplines attending a programme on hypnotherapy was conducted. Materials and Methods: The survey form consisted of 32 statements about hypnosis and hypnotherapy. Participants were asked to indicate whether they agreed, disagreed, or were not sure about each statement. A qualitative feedback form was used to obtain further views about hypnotherapy. Statistical Analysis Used: Percentage, frequency distribution. Results: The sample consisted of 21 participants from various disciplines. Two-thirds of the participants gave correct responses to statements on dangerousness of hypnosis (90%), weak mind and hypnosis (86%), and hypnosis as therapy (81%). The participants gave incorrect responses about losing control in hypnosis (57%), hypnosis being in sleep (62%), and becoming dependent on hypnotist (62%). Participants were not sure if one could not hear the hypnotist one is not hypnotized (43%) about the responses on gender and hypnosis (38%), hypnosis leading to revealing secrets (23%). -

The Application of Traditional Chinese Medicine to Western Psychotherapy: a Case Study

Open Journal of Social Sciences, 2020, 8, 265-281 https://www.scirp.org/journal/jss ISSN Online: 2327-5960 ISSN Print: 2327-5952 The Application of Traditional Chinese Medicine to Western Psychotherapy: A Case Study Chunhua Shih1, Mingjen Yang2, Jungkwang Wen3 1Department of Life and Death, Nanhua University, Chiayi County, Taiwan, China 2Dr. Yang Ming-Jen’s Psychiatric Clinic, Kaohsiung City, Taiwan, China 3Wen Xin Psychiatric Clinic, Kaohsiung City, Taiwan, China How to cite this paper: Shih, C. H., Yang, Abstract M. J., & Wen, J. K. (2020). The Application of Traditional Chinese Medicine to Western Background: Western psychological practices have traditionally treated only Psychotherapy: A Case Study. Open Journal the mind, not the body. By contrast, traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) treats of Social Sciences, 8, 265-281. both body and mind as a single gestalt. This paper presents a single case study https://doi.org/10.4236/jss.2020.85019 where Western and TCM therapies were integrated into a short-term struc- Received: April 29, 2020 tured treatment. Study Population: One male client suffering from neurotic Accepted: May 22, 2020 depression and anxiety manifesting in both emotional and physiological dis- Published: May 25, 2020 tress, including insomnia and diarrhea. One therapist participant trained in both Western psychiatric practices and TCM. Method: A course of treatment was devised combining Western psychotherapeutic technique and TCM’s diagnostic and therapy practices. Modern methods of focusing psychothe- rapy, narrative, and mindfulness were used to determine the specific trau- matic events causing the patient’s issues. Treatment was undergone by “thought imprint therapy” and finally concluded using “psychological acupuncture”. -

Areader's Guide to Pierre Janet on Dissociation: Aneglected Intellectual Heritage

AREADER'S GUIDE TO PIERRE JANET ON DISSOCIATION: ANEGLECTED INTELLECTUAL HERITAGE Onno van cler Hart, Ph. D. Barbara Friedman, M.A., M.F.C.C. Onno van der Hart, Ph.D., practices at the Institute for est to the study of Breuer and Freud (1895), others have Psychotrauma in Utrecht, The Netherlands. Barbara Fried searched for the original sources in French psychiatry, man, M.A., M.F.C.C., is in private practice in Beverly Hills, especially those of Pierre Janet. Their efforts have been California. hampered by the difficulty ofobtaining the original publica tions in French, and by the scarcity ofthese works translated For reprints write Barbara Friedman, M.A., M.F.C.C., 8665 in English translation. Wilshire Boulevard, Suite 407, Beverly Hills, CA 90211 In recent years a change has taken place with regard to Janet. The Societe PierreJanet in France has been reprint ABSTRACT ing his books since 1973. In the English-speaking world a small group of devotees has long recognized the value of A century ago there occurred a peak ofinterest in dissociation and the Janet's contribution to psychopathology and psychology. dissociative disorders, then labeled hysteria. The most important With the reprintofJanet's Major Symptoms ofHysteria in 1965, scientific and clinical investigator ofthis subject was Pierre Janet the publication of Ellenberger's The Discovery ofthe Uncon (1859-1947), whose early body of work is reviewed here. The scious in 1970, and Hilgard's Divided Consciousness in 1977, evolution of his dissociation theory and its major principles are the importance ofJanet's contribution to the study ofdisso traced throughout his writings. -

Hypnosis and Hypnotherapy

Hypnosis and Hypnotherapy What is hypnosis? Hypnosis is a treatment intervention that involves inducing the client into a relaxed, suggestible state and then offering post-hypnotic suggestions for relief of symptoms. It uses the hypnotic trance—the simple shifting back and forth between the conscious and subconscious mind, a natural process that occurs every day—in order to create this relaxed, suggestible state. What is the hypnotic trance? Many people think of hypnosis as inducing sleep. That’s actually not the case. Hypnosis (and hypnotherapy) induce the “trance state.” It is actually a natural state of mind that many of us encounter in everyday life on a regular basis. If you’ve ever been engrossed in a book, movie, or performance, then you have likely experienced the trance state. The only thing that distinguishes a naturally occurring trance state from the hypnotic trance state is that hypnotherapists induce the latter and are able to control the trance state to create understanding and healing. How is the hypnotic trance induced? Therapists use different types of hypnotic induction to get people into a trance state. The most well known and effective techniques to induce trance state is eye fixation, asking clients to stare at a spot on the ceiling or an object, or their thumb as it moves slowly backward and forward. We also teach several deepening techniques at The Wellness Institute. Most of these well established tools rely on creating deep relaxation. How is the hypnotic trance used in hypnotherapy? The hypnotic trance state creates a deep sense of relaxation and allows the client to let go. -

TVHP Acupuncture Benefits Rider (280.305)

Acupuncture Benefits Rider Your Certificate of Coverage is amended as described in 2. General Exclusions this document. This Rider becomes a part of your Contract and is subject to all provisions. Please refer to all sections The chapter in your Certificate entitled of your Contract, including your Outline of Coverage, “General Exclusions” is hereby amended. for guidelines on coverage and Cost-Sharing details. The following exclusion is STRICKEN: Acupuncture, acupressure or massage therapy; 1. Covered Services hypnotherapy, rolfing, homeopathic or The chapter in your Certificate entitled naturopathic remedies. (This exclusion does not “Covered Services” is hereby amended. apply to Medically Necessary services that would otherwise be Covered services when such services The following covered language is ADDED: are performed by a naturopath and within the scope of the naturopathic Provider’s license). Acupuncture The following exclusion is ADDED: We pay benefits for acupuncture performed by a licensed acupuncturist. You must use a Network Provider. Acupressure or massage therapy; hypnotherapy, rolfing, homeopathic or naturopathic remedies. (This exclusion does not apply to Medically Necessary The following exclusion in the Chiropractic services that would otherwise be Covered services Services section in this chapter is STRICKEN: when such services are performed by a naturopath and within the scope of the naturopathic Provider’s license). Chiropratic Services acupuncture 3. Summary Therefore, the following services are eligible for benefits and subject to the terms and conditions of your Contract, including the guidelines for coverage under your Plan: Acupuncture Don C. George President and CEO 280-305 (01/2020) The Vermont Health Plan 1. -

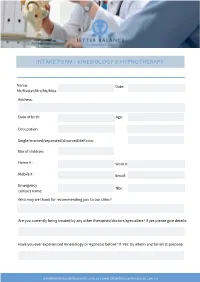

Intake Form Kinesiology & Hypnotherapy

INTAKE FORM | KINESIOLOGY & HYPNOTHERAPY Name: Date: Mr/Master/Mrs/Ms/Miss: Address: Date of birth: Age: Occupation: Single/married/separated/divorced/deFacto: Nbr of children: Home # : Work #: Mobile # : Email: Emergency Nbr: contact name: Who may we thank for recommending you to our clinic? Are you currently being treated by any other therapists/doctors/specialists? If yes please give details: Have you ever experienced Kinesiology or Hypnosis before? If ‘Yes’ by whom and for what purpose: [email protected] | www.betterbalancechiropractic.com.au MENTAL HEALTH HISTORY Have you currently or previously had any of the following? Anxiety □ currently □ previously Panic attacks □ currently □ previously Eating Disorder □ currently □ previously Chronic Insomnia □ currently □ previously Phobias □ currently □ previously Depression □ currently □ previously Addiction □ currently □ previously Compulsive □ currently □ previously Disorder □ currently □ previously Bipolar Disorder □ currently □ previously Schizophrenia □ currently □ previously Family History □ currently □ previously Other: □ currently □ previously PHYSICAL HEALTH HISTORY Have you currently or previously had any of the following? Cardiac Problems □ currently □ previously Respiratory Problems □ currently □ previously Digestive Problems □ currently □ previously Allergies □ currently □ previously Sprained Ankle/s □ currently □ previously Teeth Grinding □ currently □ previously Amalgam Fillings □ currently □ previously Thyroid Problems □ currently □ previously Skin Disorders -

Your Kaiser Permanente CHIROPRACTIC Benefits

Provided by American Specialty Health Plans of California, Inc. (ASH Plans) Your Kaiser Permanente CHIROPRACTIC benefits When you need chiropractic care, follow these simple steps: 1. Find an ASH Plans Participating Provider near you. • Online at ashlink.com/ash/kp, or • Call 1-800-678-9133 or 711 (TTY), weekdays from 5 a.m. to 6 p.m. Pacific time. 2. Schedule an appointment. 3. Pay for your office visit when you arrive for your appointment. (See the reverse for more details.) YOUR KAISER PERMANENTE CHIROPRACTIC BENEFIT Services Cost Sharing and Office Visit Maximums Chiropractic Services are covered when provided Office visit cost share: $5 copay per visit by a Participating Provider and medically necessary Office visit limit: 20 visits per year to treat or diagnose Neuromusculoskeletal Chiropractic appliance benefit: If the amount of the appliance in the ASH Plans fee Disorders. You can obtain services from any ASH schedule exceeds $50, you will pay the amount in excess of $50, and that payment will Plans Participating Provider without a referral from not apply toward any applicable deductible or out-of-pocket maximum. a Plan Physician. Covered chiropractic appliances are limited to: elbow supports, back supports, cervical collars, cervical pillows, heel lifts, hot or cold packs, lumbar braces and supports, lumbar cushions, orthotics, wrist supports, rib belts, home traction units, ankle braces, knee braces, rib supports, and wrist braces. Office visits: Covered Services are limited to Medically Necessary Chiropractic Services authorized and provided by ASH Plans Participating Providers except for Emergency Chiropractic Services and Services that are not available from Participating Providers or other licensed providers with which ASH contracts to provide covered care. -

An Introduction to the History of Hypnotism and Hypnotherapy

An introduction to the history of hypnotism and hypnotherapy In this article I have sought to put together a potted history of hypnotism and hypnotherapy through the ages. The key events and people who played the most important roles in the discoveries and developments of what has become today’s hypnotherapy treatments are the main focus of this essay. I hope this may give interested people more of an insight and understanding into the world of Hypnotherapy The early days Primitive societies used hypnotic phenomena throughout the ages for spiritual beliefs. Tribal drama and rituals, e.g. dances have been a part of many societies around the globe. This rhythmic pattern greatly assisted the participants to make the transition into a trance like state. Shamanistic rituals have played a very large part in tribal cultures around the world and there are still many cultures today where shamanism is actively practised. Shamanism is also practised in the west and has gained some credibility in most notably the new age movement. In ancient tribal cultures the shaman was the most respected member of the tribe because it was believed that not only could he commune with the spirit world and receive direct sacred knowledge that other members of the tribal community were unable to receive, but it was also believed he had special curative magical powers that could not only produce magical healings and changes in state, but he could also guide the rest of the tribe into a hypnotic state where they could also commune with the spirit world and experience a different reality.