Red November, Black November

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mother Earth

Vol. IX. December, 1914 JVo> 10 CONTENTS *i Page Special Notice to our New York Friends 305 Observations and Comments L. D. A. 306 The War and the Workers E. L. Pratt 312 Wars and Capitalism Peter Kropotkin 315 My Lectures in New York Emma Goldman 319 Emma Goldman in Chicago Margaret C. Anderson 320 Alfred Marsh I Harry Kelly 325 I San Quentin Rebekah E. Raney 327 A Ferrer Colony I 333 I Anti-Militarist League Fund 335 % Alexander Berkman Dates 33<3 ± Emma Goldman Publisher Alexander Berkman .... Editor Office: 20 East 125th Street, New York City Telephone, Harlem 6194 Price 10 Cents per Copy One Dollar per Year M"H"5"M- •H^^^^^"H"^«"H^H"M^♦•^^H"^^t Mother Earth Special Christmas Offer Dear Friends: You will no doubt purchase some gifts for your friends. Why not combine beauty with purpose? Why not help x, those you care for to see life in a new light, and at the same" 4 time lighten our burdens in the great task of human emanci pation? We have a lot of good and valuable books which we offer jj you at a very low price. Give us your order and the name and address of those you wish to surprise and we will ship, them your choice direct as coming from you. *|J $1.50 set for $1.00 "Anarchism anil Other Essays," by Emma Goldman $1.00 'What Every Mother Should Know," by Margaret Sanger. .50 Postage 15 "* $2.50 set for $2.00 * "Selected Works of Voltairlne de Cley re" $1.00 "The Social Significance of Drama," by Emma •}• Modern * Goldman 1.00 * A Play by August Strindberg 50 A Postage 25 4 $5.00 set for $3.00 A "Prison Memoirs of an Anarchist," by Alexander Berkman. -

Than a Meal: the Turkey in History, Myth

More Than a Meal Abigail at United Poultry Concerns’ Thanksgiving Party Saturday, November 22, 1997. Photo: Barbara Davidson, The Washington Times, 11/27/97 More Than a Meal The Turkey in History, Myth, Ritual, and Reality Karen Davis, Ph.D. Lantern Books New York A Division of Booklight Inc. Lantern Books One Union Square West, Suite 201 New York, NY 10003 Copyright © Karen Davis, Ph.D. 2001 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the written permission of Lantern Books. Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data For Boris, who “almost got to be The real turkey inside of me.” From Boris, by Terry Kleeman and Marie Gleason Anne Shirley, 16-year-old star of “Anne of Green Gables” (RKO-Radio) on Thanksgiving Day, 1934 Photo: Underwood & Underwood, © 1988 Underwood Photo Archives, Ltd., San Francisco Table of Contents 1 Acknowledgments . .9 Introduction: Milton, Doris, and Some “Turkeys” in Recent American History . .11 1. A History of Image Problems: The Turkey as a Mock Figure of Speech and Symbol of Failure . .17 2. The Turkey By Many Other Names: Confusing Nomenclature and Species Identification Surrounding the Native American Bird . .25 3. A True Original Native of America . .33 4. Our Token of Festive Joy . .51 5. Why Do We Hate This Celebrated Bird? . .73 6. Rituals of Spectacular Humiliation: An Attempt to Make a Pathetic Situation Seem Funny . .99 7 8 More Than a Meal 7. -

Nigeria's Resource Wars

NIGERIA’S RESOURCE WARS Edited by Egodi Uchendu University of Nigeria, Nsukka, Nigeria Series in World History Copyright © 2020 by the authors. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Vernon Art and Science Inc. www.vernonpress.com In the Americas: In the rest of the world: Vernon Press Vernon Press 1000 N West Street, Suite 1200 C/Sancti Espiritu 17, Wilmington, Delaware, 19801 Malaga, 29006 United States Spain Series in World History Library of Congress Control Number: 2020939820 ISBN: 978-1-62273-831-1 Cover design by Vernon Press. Cover image designed by rawpixel.com / Freepik. Product and company names mentioned in this work are the trademarks of their respective owners. While every care has been taken in preparing this work, neither the authors nor Vernon Art and Science Inc. may be held responsible for any loss or damage caused or alleged to be caused directly or indirectly by the information contained in it. Every effort has been made to trace all copyright holders, but if any have been inadvertently overlooked the publisher will be pleased to include any necessary credits in any subsequent reprint or edition. Nigeria’s current delineation into six geo-political zones. © Egodi Uchendu 2020. Table of contents List of Figures xi List of Tables xv List of Abbreviations xvii Acknowledgements xxiii Preface xxv Egodi Uchendu University of Nigeria, Nsukka, Nigeria Introduction: The Struggle for Equitable and Efficient Natural Resource Allocation in Nigeria liii John Mukum Mbaku Weber State University, Utah, USA Part 1. -

Black Women's Youtube Channels in Brazil As Fortalecimento

Black Faces in White Spaces: Black Women’s YouTube Channels in Brazil as Fortalecimento ALIDA PERRINE University of Texas, Austin Abstract: A large and growing network of black women YouTubers in Brazil mobilize strategies of fortalecimento, a term used by some women to refer to how they prepare themselves to face the barriers created by the gendered racial hierarchy of Brazilian society. In this article, I examine these YouTube channels and the tactics black women use to increase their own visibility, to value black aesthetics, and to denounce racist and sexist acts or representations. Furthermore, I consider the importance of physical spaces, such as production studios, for YouTube success, and how black women negotiate material spaces as well as the video sharing platform to maximize their visibility and encroach on predominantly white spaces of cultural production. Using theories of intersectionality, representation, and subjecthood, I examine how these women use (virtual) communities to re-signify and pluralize black womanhood in Brazil. Keywords: Racism, sexism, social media, representation, cultural resistance When Nátaly Neri, a 21-year-old black college student, started her YouTube channel in 2015, it was one among thousands of other channels containing do-it- yourself videos about sewing and hairstyles. Scrolling through her videos, one finds showcases of thrift-store finds transformed into the unique fashion that defines Neri’s style, as well as detailed documentation of her transitions from braids to dreads and beyond. For many young black women like Neri with channels on YouTube, not just in Brazil but throughout the diaspora, haircare and styling is a common entry point to the practice of self-vlogging. -

Black Friday

C M Y K A guide to squeezing in all EWS UN your holiday merry-making NHighlands County’s Hometown-S Newspaper Since 1927 PAGE 14B Run hard ... then eat Being together 19th Turkey Trot draws Salvation Army hosts hundreds to Hammock Thanksgiving dinner SPORTS, 1B PHOTOS, 6A Sunday, November 27, 2011 www.newssun.com Volume 92/Number 140 | 75 cents Forecast County ‘throwing money’ Partly sunny, then at ‘shell of a building’ breezy in the PM High Low By ED BALDRIDGE Barbara Stewart took excep- total allocated funds for the [email protected] tion to an additional $100,000 project – including the pur- SEBRING — County com- of unbudgeted requests from chases, expenses and an addi- 82 63 missioners showed concern County Engineer Ramon tional $632,464 in encum- Complete Forecast over the costs of a recently Gavarrete to weatherize the bered but unspent funds – PAGE 14A purchased building on building purchased at 4500 N. added up to just more than Tuesday, pointing out that Kenilworth Blvd. $2.1 million for the property Online News-Sun photo by ED BALDRIDGE staff was not diligent on pro- The building was bought to and repairs in addition to the On the outside, the Kenilworth Business Center looks new and professional, but county engineer Ramon tecting taxpayer money. house the Supervisor of latest $100,000 request. Gavarrete told commissioners the $2.1 million taxpayer Just more than five hours Elections offices. Stewart insisted that she investment was “just a shell” with holes in the ceiling into the seven-hour board County budget staff and needed proper permitting. -

Nollywood Interventions in Niger Delta Oil Conflicts: a Study of Jeta Amata's Black November

NOLLYWOOD INTERVENTIONS IN NIGER DELTA OIL CONFLICTS: A STUDY OF JETA AMATA'S BLACK NOVEMBER Emmanuel Onyekachukwu Ebekue* & Michael Chidubem Nwoye* http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/og.v15i1.6 Abstract The discovery of oil in Oloibiri town in the Niger Delta region of southern Nigeria in 1956 has brought with it myriads of problems to the region. There has been lingering crisis in the region which has led to repeated loss of lives and properties. There have been countless efforts at finding a permanent solution to the conflict. However, there seems to be a renewed agitation and restiveness resulting from the stoppage of the amnesty program that was instituted by the late President YarAdua’s federal government. It is against this background that the researcher embarked on this work in order to critically x-ray Nollywood’s contribution to the peace effort with a special attention to JetaAmata’s Black November (2012). The researcher used the case study approach of the qualitative research method in analyzing his data. Findings from the research showed that any solution to the lingering crisis aimed at long term must adopt a populist approach. Key Words: Nollywood, Niger Delta, Oil, Conflict, Intervention 1.0 Introduction The importance of film in human society has been underscored by critics. However, the potential of the film medium are yet to be fully utilized for national uplift and human development. Many countries of the world with the United States of America (USA) and India at the vanguard have used the film medium to give their people a better life. -

The Rise of Ethical Anarchism in Britain, 1885-1900

1 e[/]pater 2 sie[\]cle THE RISE OF ETHICAL ANARCHISM IN BRITAIN 1885-1900 By Mark Bevir Department of Politics Newcastle University Newcastle upon Tyne NE1 7RU U.K. ABSTRACT In the nineteenth century, anarchists were strict individualists favouring clandestine organisation and violent revolution: in the twentieth century, they have been romantic communalists favouring moral experiments and sexual liberation. This essay examines the growth of this ethical anarchism in Britain in the late nineteenth century, as exemplified by the Freedom Group and the Tolstoyans. These anarchists adopted the moral and even religious concerns of groups such as the Fellowship of the New Life. Their anarchist theory resembled the beliefs of counter-cultural groups such as the aesthetes more closely than it did earlier forms of anarchism. And this theory led them into the movements for sex reform and communal living. 1 THE RISE OF ETHICAL ANARCHISM IN BRITAIN 1885-1900 Art for art's sake had come to its logical conclusion in decadence . More recent devotees have adopted the expressive phase: art for life's sake. It is probable that the decadents meant much the same thing, but they saw life as intensive and individual, whereas the later view is universal in scope. It roams extensively over humanity, realising the collective soul. [Holbrook Jackson, The Eighteen Nineties (London: G. Richards, 1913), p. 196] To the Victorians, anarchism was an individualist doctrine found in clandestine organisations of violent revolutionaries. By the outbreak of the First World War, another very different type of anarchism was becoming equally well recognised. The new anarchists still opposed the very idea of the state, but they were communalists not individualists, and they sought to realise their ideal peacefully through personal example and moral education, not violently through acts of terror and a general uprising. -

The Iwma in Belgium (1865–1875)

chapter 9 The iwma in Belgium (1865–1875) Jean Puissant Translation from the French by Angèle David-Guillou From the first histories of socialism in Belgium, written initially by militants then by professional historians from the 1950s, the International Working Men’s Association (iwma) has been presented as a founding moment, or at least as an important one, in the evolution towards the creation of the Belgium labour party, Parti ouvrier belge (pob) in 1885, and later on that of its succes- sors – the Belgium socialist party, psb-bsp in 1945 and the current socialist parties, the French-speaking ps and the Dutch-speaking sp/ao. One hundred years after the creation of the pob, in 1985, most of the socialist federations still traced the origin of their party back to the iwma. This extremely linear genealogical approach had given way to a historiographic tradition that was only challenged in 2000.1 A new wave of historical research in the years 1950 to 1980 produced numerous studies, including substantial publications of source materials2 which, combined with the general histories of the iwma, formed an excep- tional body of original documents – a rare thing in the field of the history of social organisations. If the harvest was not as fruitful in the following years,3 our general understanding of the subject was refined by biographies.4 Finally, through abundant cross-studies, the work of Freddy Joris helped us understand why the Verviers regional federation – a wool world centre at the time – had been the most important federation and survived the longest of all. -

Remembering Ludlow but Forgetting the Columbine: the 1927-1928 Colorado Coal Strike

Remembering Ludlow but Forgetting the Columbine: The 1927-1928 Colorado Coal Strike By Leigh Campbell-Hale B.A., University of Arkansas, Fayetteville, 1977 M.A., University of Colorado, Boulder, 2005 A dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Colorado and Committee Members: Phoebe S.K. Young Thomas G. Andrews Mark Pittenger Lee Chambers Ahmed White In partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History 2013 This thesis entitled: Remembering Ludlow but Forgetting the Columbine: The 1927-1928 Colorado Coal Strike written by Leigh Campbell-Hale has been approved for the Department of History Phoebe S.K. Young Thomas Andrews Date The final copy of this thesis has been examined by the signatories, and we Find that both the content and the form meet acceptable presentation standards Of scholarly work in the above mentioned discipline. ii Campbell-Hale, Leigh (Ph.D, History) Remembering Ludlow but Forgetting the Columbine: The 1927-1928 Colorado Coal Strike Dissertation directed by Associate Professor Phoebe S.K. Young This dissertation examines the causes, context, and legacies of the 1927-1928 Colorado coal strike in relationship to the history of labor organizing and coalmining in both Colorado and the United States. While historians have written prolifically about the Ludlow Massacre, which took place during the 1913- 1914 Colorado coal strike led by the United Mine Workers of America, there has been a curious lack of attention to the Columbine Massacre that occurred not far away within the 1927-1928 Colorado coal strike, led by the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW). -

Masa Bulletin

masa bulletin IN THIS COLUMN we shall run discussions of MASSIVE MASA MEETING: As Yr. F. E. issues raised by the several chapters of the Amer writes this it is already two weeks beyond the ican Studies Association. This is in response to a date on which programs and registration forms request brought to us from the Council of the were to have been mailed. The printer, who has ASA at its Fall 1981 National Meeting. ASA had copy for ages, still has not delivered the pro members with appropriate issues on their minds grams. Having, in a moment of soft-headedness, are asked to communicate with their chapter of allowed himself to be suckered into accepting ficers, to whom we open these pages, asking only the position of local arrangements chair, he has that officers give us a buzz at 913-864-4878 to just learned that Haskell Springer, program alert us to what's likely to arrive, and that they chair, has been suddenly hospitalized, so that he keep items fairly short. will, for several weeks at least, have to take over No formal communications have come in yet, that duty as well. Having planned to provide though several members suggested that we music for some informal moments in the Spen prime the pump by reporting on the discussion cer Museum of Art before a joint session involv of joint meetings which grew out of the 1982 ing MASA and the Sonneck Society, he now finds that the woodwind quintet in which he MASA events described below. plays has lost its bassoonist, apparently irreplac- Joint meetings, of course, used to be SOP. -

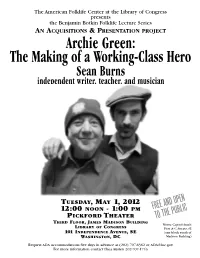

Archie Green, a Botkin Series Lecture by Sean Burns, American Folklife

The American Folklife Center at the Library of Congress presents the Benjamin Botkin Folklife Lecture Series AN ACQUISITIONS & PRESENTATION PROJECT Archie Green: The Making of a Working-Class Hero Sean Burns independent writer, teacher, and musician TUESDAY, MAY 1, 2012 D OPENFREE AN 12:00 NOON - 1:00 PM PICKFORD THEATER PUBLICTO THE THIRD FLOOR, JAMES MADISON BUILDING Metro: Capitol South LIBRARY OF CONGRESS First & C Streets, SE 101 I NDEPENDENCE AVENUE, SE (one block south of WASHINGTON, DC Madison Building) Request ADA accommodations five days in advance at (202) 707-6362 or [email protected] For more information contact Thea Austen 202-707-1743 Archie Green: The Making of a Working-Class Hero Sean Burns Respected as one of the great public intellectuals and his subsequent development of laborlore as a of the twentieth century, Archie Green (1917-2009), public-oriented interdisciplinary field. Burns will through his prolific writings and unprecedented explore laborlore’s impact on labor history, folklore, public initiatives on behalf of workers’ folklife, and American cultural studies and place these profoundly contributed to the philosophy and implications within the context of the larger “cultural practice of cultural pluralism. For Green, a child of turn” of the humanities and social sciences during Ukrainian immigrants, pluralism was the life-source the last quarter of the 20th century. When Green of democracy, an essential antidote to advocated in the late 1960s for the Festival of authoritarianism of every kind, which, for his American Folklife to include skilled manual laborers generation, most notably took the forms of fascism displaying their craft on the National Mall, this was and Stalinism. -

Anarchism, Individualism and Communism: William Morris's Critique of Anarcho-Communism

Loughborough University Institutional Repository Anarchism, individualism and communism: William Morris's critique of anarcho-communism This item was submitted to Loughborough University's Institutional Repository by the/an author. Citation: KINNA, R., 2012. Anarchism, individualism and communism: William Morris's critique of anarcho-communism. IN: Prichard, A. ... et al (eds). Liber- tarian Socialism: Politics in Black and Red. Houndsmill, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, pp.35-56. Additional Information: • This is a book chapter. It is reproduced with permission of Palgrave Macmillan. This extract is taken from the author's original manuscript and has not been edited. The definitive, published, version of record is available here: www.palgrave.com Metadata Record: https://dspace.lboro.ac.uk/2134/12730 Version: Accepted for publication Publisher: Palgrave MacMillan ( c Alex Prichard, Ruth Kinna, Saku Pinta and Dave Berry) Please cite the published version. This item was submitted to Loughborough’s Institutional Repository (https://dspace.lboro.ac.uk/) by the author and is made available under the following Creative Commons Licence conditions. For the full text of this licence, please go to: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/2.5/ 3 Anarchism, Individualism and Communism: William Morris’s Critique of Anarcho- communism Ruth Kinna Introduction William Morris’s commitment to revolutionary socialism is now well established, but the nature of his politics, specifically his relationship to Marxism and anarchist thought, is still contested. Perhaps, as Mark Bevir has argued, the ideological label pinned to Morris’s socialism is of ‘little importance’ for as long as his political thought is described adequately. Nevertheless, the starting point for this essay is that thinking about the application of ideological descriptors is a useful exercise and one which sheds important light on Morris’s socialism and the process of ideological formation in the late nineteenth-century socialist movement.