A History of Hermann Park

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hermann Park Japanese Garden Day Honors 40 Years of Friendship

Estella Espinosa Houston Parks and Recreation Department 2999 South Wayside Houston, TX 77023 Office: (832) 395-7022 Cell: (832) 465-4782 Alisa Tobin Information & Cultural Affairs Consulate-General of Japan 909 Fannin, Suite 3000 Houston, Texas 77010 Office: (713) 287-3745 Release Date: 06/15/2012 (REVISED) Hermann Park Japanese Garden Day Honors 40 Years of Friendship Between COH & Chiba City, Japan 20 Cherry Blossom Trees to Be Planted As Part of Centennial Celebration of Tree Gift to US from Japan Mayor Annise Parker will recognize Mr. Kunio Minami, local community groups, & many individuals for their dedication & work to the maintenance of one of Houston's most enduring symbols of friendship, the Japanese Garden at Hermann Park. In recognition of this dedication & in honor of the friendship between the City of Houston & its sister city, Chiba City, Japan, Tuesday, June 19 will be proclaimed Hermann Park Japanese Garden Day in the City of Houston. "For the past two decades, the Japanese Garden has served as a visible symbol of the friendship between Houston & Chiba City," said Houston Mayor Annise Parker. "We are truly honored to acknowledge the lasting friendship this garden personifies, with its beautiful pathways, gardens, & trees." In 1912, the People of Japan gave to the People of the United States 3,000 flowering cherry trees as a gift of friendship. In commemoration of this centennial & in recognition of the 40th anniversary of the Houston-Chiba City sister city relationship, 20 new cherry trees will be planted in the Japanese Garden in Hermann Park in October of this year. -

Motorcycle Parking

C am b rid ge Memorial S Hermann t Medical Plaza MOTORCYCLE PARKING Motorcycle Parking 59 Memorial Hermann – HERMANN PARK TO DOWNTOWN TMC ay 288 Children’s r W go HOUSTON Memorial re G Hermann c HOUSTON ZOO a Hospital M Prairie View N A&M University Way RICE egor Gr Ros ac UNIVERSITY The Methodist UTHealth s M S MOTORCYCLE S Hospital Outpatient te PARKING Medical rl CAMPUS Center MOTORCYCLE in p School PARKING g o Av Garage 4 o Garage 3 e L West t b S u C J HAM– a am Pavilion o n T d St h e en TO LELAND n St n n Fr TMC ll D i i Library r a n e u n ema C ANDERSON M a E Smith F MOTORCYCLE n Tower PARKING Bl CAMPUS vd Garage 7 (see inset) Rice BRC Building Scurlock Tower Mary Gibbs Ben Taub Jones Hall Baylor College General of Medicine Hospital Houston Wilk e Methodist i v ns St A C a Hospital g m M in y o MOTORCYCLE b a John P. McGovern u PARKING r MOTORCYCLE r TIRR em i W Baylor PARKING TMHRI s l d TMC Commons u F r nd St Memorial g o Clinic Garage 6 r e g Garage 1 Texas Hermann a re The O’Quinn m S G Children’s a t ac Medical Tower Mitchell NRI L M at St. Luke’s Building Texas Children’s (BSRB) d Main Street Lot e Bellows Dr v l Texas v D B A ix Children’s Richard E. -

Protected Landmark Designation Report

CITY OF HOUSTON Archaeological & Historical Commission Planning and Development Department PROTECTED LANDMARK DESIGNATION REPORT LANDMARK NAME: Sam Houston Park (originally known as City Park) AGENDA ITEM: III.a OWNER: City of Houston HPO FILE NO.: 06PL33 APPLICANT: City of Houston Parks and Recreation Department and DATE ACCEPTED: Oct-20-06 The Heritage Society LOCATION: 1100 Bagby Street HAHC HEARING DATE: Dec-21-06 30-DAY HEARING NOTICE: N/A PC HEARING DATE: Jan-04-07 SITE INFORMATION: Land leased from the City of Houston, Harris County, Texas to The Heritage Society authorized by Ordinance 84-968, dated June 20, 1984 as follows: Tract 1: 42, 393 square feet out of Block 265; Tract 2: 78,074 square feet out of Block 262, being part of and out of Sam Houston Park, in the John Austin Survey, Abstract No. 1, more fully described by metes and bounds therein; and Tract 3: 11,971 square feet out of Block 264, S. S. B. B., and part of Block 54, Houston City Street Railway No. 3, John Austin Survey, Abstract 1, more fully described by metes and bounds therein, Houston, Harris County, Texas. TYPE OF APPROVAL REQUESTED: Landmark and Protected Landmark Designation for Sam Houston Park. The Kellum-Noble House located within the park is already designated as a City of Houston Landmark and Protected Landmark. HISTORY AND SIGNIFICANCE SUMMARY: Sam Houston Park is the first and oldest municipal park in the city and currently comprises nineteen acres on the edge of the downtown business district, adjacent to the Buffalo Bayou parkway and Bagby Street. -

Houston's Oldest House Gets a New Life

PRESERVATION Houston’s Oldest House Gets a New Life By Ginger Berni The exterior of the newly renovated Kellum-Noble House in 2019. All photos courtesy of The Heritage Society unless otherwise noted. hose familiar with Houston history may be able to tell The narratives used to interpret the house have changed Tyou that the oldest house in the city still standing on its over time, with certain details of its history emphasized, original property is the 1847 Kellum-Noble House in Sam while others were largely ignored. Like many historic Houston Park. Although owned by the City of Houston, house museums, Kellum-Noble featured traditional antique The Heritage Society (THS), a non-profit organization, has furnishings for a parlor, dining room, office, and bedrooms, maintained the home for the past sixty-five years. Recently, while a tour guide explained to visitors the significance THS completed phase two of an ambitious three-phased of the building. Emphasis was often placed on discussing project to stabilize the building’s foundation and address the Sam Houston simply because he knew the original owner, significant cracks in the brick walls. Its story, however, goes Nathaniel Kellum, and Houston’s descendants had donat- much deeper than the bricks that make up the building. ed some of the featured collections. Yet the importance of Zerviah Noble’s efforts to educate local Houstonians, first using the house as a private school, then as one of its first public schools, was not communicated through the home’s furnishings. Perhaps most importantly, any discussion of the enslaved African Americans owned by the Kellums and the Nobles was noticeably absent — a practice that is not un- common in historic house museums throughout the country and particularly in the South. -

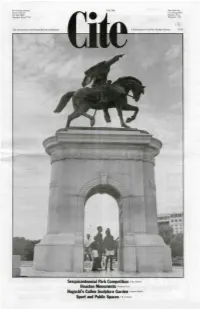

Sesquicentennial Park Competition **« N*»« Houston

Rice Design Alliance Fall 1986 Non-Pmfil Org. Rice University U.S. Postage Paid P.O. Box 1892 Houston. Texas Houslon, Texas 77251 Permit No. 754" The Architecture and Design Review of Houston \ Publication oflhe Rice Design Alliance $3.00 Sesquicentennial Park Competition **« n*»« Houston Monuments Stephen FOX Noguchi's Cullen Sculpture Garden ^-» »••«'- Sport and Public SpacesJ B •'«•«» Cite Flit 1986 InCite 4 Citelines 8 ForeCite L\ 8 The Sesquicentennial Park Design Competition Cite 12 Remember Houston 14 Romancing the Stone: The Cullen Sculpture Garden PlANTS 16 Fields of Play: Sport and Public Spaces Cover: Sam Houston Monument. Hermann 17 Citesurvey: Rubenstein Park. 1925, Enrico F. Cerracchio. sculptor. Group Building J. W. Northrop. Jr., architect (Photo by 18 Citeations ARETHE Paul Hester) 23 Hind Cite NATURE Editorial Committee Thomas Colbert Neil Printz John Gilderbloom Malcolm Quantril! Bruce C. Webb Elizabeth S. Glassman Eduardo Robles Chairman David Kaplan William F. Stern Phillip Lopate Drexel Turner OF OUR Jeffrey Karl Ochsner Peter D. Waldman BUSINESS Guest Editor: Drexel Turner The opinions expressed in Cite do not Managing Editor: Linda Leigh Sylvan necessarily represent the views of the Editorial Assistant: Nancy P, Henry Board of Directors of the Rice Design Graphic Designer: Alisa Bales Alliance. Typesetting and Production: Baxt & Associates Cite welcomes unsolicited manuscripts. Director of Advertising: Authors take full responsibility for Kathryn Easterly securing required consents and releases Publisher: Lynette M. Gannon and for the authenticity of their articles. All manuscripts will be considered by the During our thirty years in business The Spencer Company's client list Publication of this issue of Cite is Editorial Board. -

Where's the Revolution?

[Where’s the] 32 REVOLUTION The CHANGING LANDSCAPE of Free Speech in Houston. FALL2009.cite CLOCKWISE FROM TOP: Menil Collection north lawn; strip center on Memorial Drive; “Camp Casey” outside Crawford, Texas; and the George R. Brown Convention Center. 1984, Cite published an essay by Phillip Lopate en- titled “Pursuing the Unicorn: Public Space in Hous- ton.” Lopate lamented: “For a city its size, Houston has an almost sensational lack of convivial public space. I mean places where people congregate on their own for the sheer pleasure of being part of a INmass, such as watching the parade of humanity, celebrating festivals, cruis- ing for love, showing o! new clothing, meeting appointments ‘under the old clock,’ bumping into acquaintances, discussing the latest political scandals, and experiencing pride as city dwellers.” Twenty-seven years later, the lament can end. After the open- the dawn of a global day of opposition. In London between ing of Discovery Green, the Lee and Joe Jamail Skatepark, 75,000 and two million were already protesting. For Rome, and the Lake Plaza at Hermann Park, the city seems an alto- the estimates ranged from 650,000 to three million. Between gether different place. The skyline itself feels warmer and 300,000 and a million people were gathering in New York more humane when foregrounded by throngs of laughing City, and 50,000 people would descend upon Los Angeles children of all stripes. The strenuous civic activity of count- later in the day. less boosters and offi cials to make these fabulous public Just after noon, when the protest in Houston was sched- spaces is to be praised. -

DOWNTOWN HOUSTON, TEXAS LOCATION Situated on the Edge of the Skyline and Shopping Districts Downtown, 1111 Travis Is the Perfect Downtown Retail Location

DOWNTOWN HOUSTON, TEXAS LOCATION Situated on the edge of the Skyline and Shopping districts Downtown, 1111 Travis is the perfect downtown retail location. In addition to ground level access. The lower level is open to the Downtown tunnels. THE WOODLANDS DRIVE TIMES KINGWOOD MINUTES TO: Houston Heights: 10 minutes River Oaks: 11 minutes West University: 14 minutes Memorial: 16 minutes 290 249 Galleria: 16 minutes IAH 45 Tanglewood: 14 minutes CYPRESS Med Center:12 minutes Katy: 31 minutes 59 Cypress: 29 minutes 6 8 Hobby Airport: 18 minutes 290 90 George Bush Airport: 22 minutes Sugar Land: 25 minutes 610 Port of Houston: 32 minutes HOUSTON 10 HEIGHTS 10 Space Center Houston: 24 minutes MEMORIAL KATY 10 330 99 TANGLEWOOD PORT OF Woodlands: 31 minutes HOUSTON 8 DOWNTOWN THE GALLERIA RIVER OAKS HOUSTON Kingwood: 33 minutes WEST U 225 TEXAS MEDICAL 610 CENTER 99 90 HOBBY 146 35 90 3 59 SPACE CENTER 45 HOUSTON SUGARLAND 6 288 BAYBROOK THE BUILDING OFFICE SPACE: 457,900 SQ FT RETAIL: 17,700 SQ FT TOTAL: 838,800 SQ FT TRAVIS SITE MAP GROUND LEVEL DALLAS LAMAR BIKE PATH RETAIL SPACE RETAIL SPACE METRO RAIL MAIN STREET SQUARE STOP SITE MAP LOWER LEVEL LOWER LEVEL RETAIL SPACE LOWER LEVEL PARKING TUNNEL ACCESS LOWER LEVEL PARKING RETAIL SPACE GROUND LEVEL Main Street Frontage 3,037 SQ FT 7,771 SQ FT RETAIL SPACE GROUND LEVEL Main Street frontage Metro stop outside door Exposure to the Metro line RETAIL SPACE GROUND LEVEL Houston’s Metro Rail, Main Street Square stop is located directly outside the ground level retail space. -

SAM HOUSTON PARK: Houston History Through the Ages by Wallace W

PRESERVATION The 1847 Kellum-Noble House served as Houston Parks Department headquarters for many years. Photo courtesy of Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, HABS, Reproduction number HABS TEX, 101-HOUT, 4-1. SAM HOUSTON PARK: Houston History through the Ages By Wallace W. Saage he history of Texas and the history of the city grant from Austin’s widow, Mrs. J. F. L. Parrot, and laid Tof Houston are inextricably linked to one factor out a new city.1 They named it Houston. – land. Both Texas and Houston used the legacy of The growth of Sam Houston Park, originally called the land to encourage settlement, bringing in a great City Park, has always been closely related to the transfer multicultural mélange of settlers that left a lasting im- of land, particularly the physical and cultural evolution pression on the state. An early Mexican land grant to of Houston’s downtown region that the park borders. John Austin in 1824 led to a far-reaching development Contained within the present park boundaries are sites ac- plan and the founding of a new city on the banks of quired by the city from separate entities, which had erected Buffalo Bayou. In 1836, after the Republic of Texas private homes, businesses, and two cemeteries there. won its independence, brothers John Kirby Allen and Over the years, the city has refurbished the park, made Augustus C. Allen purchased several acres of this changes in the physical plant, and accommodated the increased use of automobiles to access a growing downtown. The greatest transformation of the park, however, grew out of the proposed demoli- tion of the original Kellum House built on the site in 1847. -

Final Report September 4, 2015

Final Report September 4, 2015 planhouston.org Houston: Opportunity. Diversity. Community. Home. Introduction Houston is a great city. From its winding greenways, to its thriving arts and cultural scene, to its bold entrepreneurialism, Houston is a city of opportunity. Houston is also renowned for its welcoming culture: a city that thrives on its international diversity, where eclectic inner city neighborhoods and master-planned suburban communities come together. Houston is a place where all of us can feel at home. Even with our successes, Houston faces many challenges: from managing its continued growth, to sustaining quality infrastructure, enhancing its existing neighborhoods, and addressing social and economic inequities. Overcoming these challenges requires strong and effective local government, including a City organization that is well-coordinated, pro-active, and efficient. Having this kind of highly capable City is vital to ensuring our community enjoys the highest possible quality of life and competes successfully for the best and brightest people, businesses, and institutions. In short, achieving Houston’s full potential requires a plan. Realizing this potential is the ambition of Plan Houston. In developing this plan, the project team, led by the City’s Planning and Development Department, began by looking at plans that had previously been created by dozens of public and private sector groups. The team then listened to Houstonians themselves, who described their vision for Houston’s future. Finally, the team sought guidance from Plan Houston’s diverse leadership groups – notably its Steering Committee, Stakeholder Advisory Group and Technical Advisory Committee – to develop strategies to achieve the vision. Plan Houston supports Houston’s continued success by providing consensus around Houston’s goals and policies and encouraging coordination and partnerships, thus enabling more effective government. -

The Jewish Mardi Gras? Celebrate Purim with Emanu

March 3, 2020 I 7 Adar 5780 Bulletin VOLUME 74 NUMBER 6 FROM RABBI HAYON Sisterhood to Host Barbara Pierce Bush as 2020 The Jewish Mardi Gras? Fundraiser Speaker Now that March is here, we have arrived at Thursday, March 26, 11:30 a.m. what is said to be the most joyous time of Congregation the Jewish year. We are now in the Hebrew Emanu El month of Adar, and our tradition teaches: Sisterhood, in “When Adar begins, rejoicing multiplies.” partnership with the Barbara Jewish happiness reaches its apex during Adar because Bush Literacy it is the time of Purim, when convention and inhibition Foundation and Purim’s purpose is dissipate. During Purim we allow ourselves to indulge in Harris County to help us realize all sorts of fun as a way of commemorating our people’s Public Library, the potential of miraculous escape from Haman’s wicked plot in the an- will hold its transformative cient kingdom of Persia. annual fundraising event, Words joy, but it insists Change the World this month. This that enduring But we are not alone in our religious celebrations at this time of year. We’re all familiar with the raucous traditions year’s guest speaker will be Barbara happiness emerges Pierce Bush, humanitarian and co- less from satisfying associated with Mardi Gras, but we don’t often pause to recall that those celebrations are also rooted in religious founder and Board Chair of Global our own appetites Health Corps. than from working traditions of their own: the reason for the Christian tra- dition of indulging on Fat Tuesday is that it occurs imme- for the preserva- A Yale University graduate with a tion of others. -

Independence Trail Region, Known As the “Cradle of Texas Liberty,” Comprises a 28-County Area Stretching More Than 200 Miles from San Antonio to Galveston

n the saga of Texas history, no era is more distinctive or accented by epic events than Texas’ struggle for independence and its years as a sovereign republic. During the early 1800s, Spain enacted policies to fend off the encroachment of European rivals into its New World territories west of Louisiana. I As a last-ditch defense of what’s now Texas, the Spanish Crown allowed immigrants from the U.S. to settle between the Trinity and Guadalupe rivers. The first settlers were the Old Three Hundred families who established Stephen F. Austin’s initial colony. Lured by land as cheap as four cents per acre, homesteaders came to Texas, first in a trickle, then a flood. In 1821, sovereignty shifted when Mexico won independence from Spain, but Anglo-American immigrants soon outnumbered Tejanos (Mexican-Texans). Gen. Antonio López de Santa Anna seized control of Mexico in 1833 and gripped the country with ironhanded rule. By 1835, the dictator tried to stop immigration to Texas, limit settlers’ weapons, impose high tariffs and abolish slavery — changes resisted by most Texans. Texas The Independence ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ Trail ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ On March 2, 1836, after more than a year of conclaves, failed negotiations and a few armed conflicts, citizen delegates met at what’s now Washington-on-the-Brazos and declared Texas independent. They adopted a constitution and voted to raise an army under Gen. Sam Houston. TEXAS STATE LIBRARY AND ARCHIVES Gen. Sam Houston THC The San Jacinto Monument towers over the battlefield where Texas forces defeated the Mexican Army. TEXAS HISTORICAL COMMISSION Four days later, the Alamo fell to Santa Anna. -

Houston // Texas 2 — Contents 3

HOUSTON // TEXAS 2 — CONTENTS 3 CONTENTS Overview 04 The Heart of the Theater District 08 Anchors 10 Site Plans 12 Offices 18 Houston 22 The Cordish Companies 26 4 — OVERVIEW 5 WELCOME TO BAYOU PLACE In the heart of Houston’s renowned Theater District, Bayou Place is the city’s premier dining, office, and entertainment district. Alongside the Hobby Center for the Performing Arts, the Alley Theatre, and the Wortham Theater Center, Bayou Place boasts its own flexible performance space, Revention Music Center, as well as Sundance Cinemas. 6 — OVERVIEW 7 $47M OFFICE & $25M $22M 150K 3M OFFICE SPACE ENTERTAINMENT SQUARE FEET OF THEATER DISTRICT ENTERTAINMENT DISTRICT EXPANSION DEVELOPMENT OFFICE SPACE TICKETS SOLD ANNUALLY 8 — HEART OF THE THEATER DISTRICT 9 10 11 1 2 12 3 4 6 7 5 9 8 THE HEART OF THE THEATER DISTRICT 1 Wortham Center 7 City Hall 2 Alley Theatre 8 Sam Houston Park 3 Jones Hall 9 Heritage Plaza ON WITH 4 Downtown Aquarium 10 Minute Maid Park 5 The Hobby Center 11 George R. Brown Convention Center THE SHOWS 6 Tranquility Park 12 Toyota Center 10 — ANCHORS 11 ANCHOR TENANTS PREMIER RESTAURANTS, THEATERS, AND BUSINESSES 12 — SITE PLANS 13 RESTAURANTS & BARS Hard Rock Cafe Little Napoli Italian Cuisine The Blue Fish NIGHTLIFE & ENTERTAINMENT SITE PLAN Sundance Cinemas Revention Music Center FIRST KEY Retail Office FLOOR Parking 14 — SITE PLANS 15 SITE PLAN SECOND FLOOR RESTAURANTS & BARS Hard Rock Cafe OFFICES SoftLayer Merrill Corporation NIGHTLIFE & ENTERTAINMENT Sundance Cinemas Revention Music Center The Ballroom at Bayou Place KEY Retail Office Parking 16 17 3M+ ANNUAL VISITORS 18 — OFFICES 19 150,000 SQUARE FEET OF CLASS A OFFICE SPACE 20 — OFFICES 21 22 — HOUSTON 23 HOUSTON BAYOU CITY Founded along Buffalo Bayou, site of the final battle for Texas independence, Houston is the largest city by population in Texas and the fourth largest in the United States.