The Case of US Bank Stadium

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hoover Metropolitan Stadium: Home of the Birmingham Ba 5 Beam Clay Awards a History Maker by Bob Tracinski

http://www.sportsturfonline.com Hoover Metropolitan Stadium: Home of the Birmingham Ba 5 Beam Clay awards a history maker by Bob Tracinski he Birmingham Barons' the first of its 12 Southern League titles petitions, and church festivals. The Hoover Metropolitan in 1906. Southeastern Conference Baseball T Stadium made awards Birmingham millionaire industrialist Tournament came to the Met in 1990 history when it was named the STMA / A. H. (Rick) Woodward bought the team and 1996, and will return for a four- sportsTURF / Beam Clay 1997 in 1910. He moved it to the first concrete year stint in 1998. Professional Baseball Diamond "of the and steel ballpark in the minor leagues: "Millions viewed the Met on TV Year. For the first time, the same head the 12.7-acre Rickwood Field. It served when basketball's Michael Jordan groundskeeper has been honored twice as the Barons' home field until 1987. joined the Barons for the 1994 season," for his work at two different facilities The City of Hoover built Hoover says Horne. "Home field attendance and at two different levels of baseball. Metropolitan Stadium in 1987. ballooned to 467,867, and Dave Steve Horne, the Elmore's Elmore Sports Barons' director of field Group bought the Barons operations during the the following year. In 1996 award-winning 1997 sea- the team started its sec- son, was head ond decade of affiliation groundskeeper/stadium with the Chicago White -manager at the University Sox." of Mississippi when These events led to a Swayze Field was selected major field renovation in College Baseball Diamond 1996. -

San Antonio Sports Hall of Fame Auction Items

SAN ANTONIO SPORTS HALL OF FAME TRIBUTE AUCTION FEBRUARY 10, 2005 Instructions for the Auction: 1. Please follow the instructions on the Bid Sheets for the silent auction. 2. Minimum Bid is the Starting Bid. 3. Incremental Increases should be followed or your Bid will be deleted unless it is higher than required. 4. Please note all Gift Certificates have expiration dates. 5. Check out will begin after all the Inductees have been presented. 6. Visa, MasterCard or American Express, Cash and Checks are accepted. 7. Live Auction will be paid for immediately by successful bidder. Bid High & Good Luck! Page 1 Live Auction 1……….Mexican Fiesta Party at Rio Plaza Courtyard Party for up to 75 friends at Rio Plaza on the Riverwalk; Mexican Buffet and 'Tex Mex' drinks to include Margaritas, Wine and Beer accompanied by light entertainment. Book Soon! Based on Availability. Value $2,500 Donated by Rio Plaza and Weston Events 2……….Wine Lovers Extravaganza Explore the Napa Valley with a Weekend for Two at Trinchero Estates Bed & Breakfast known for their world class wines and located in the heart of the wine country with gourmet Breakfasts, Tour & Tasting. Additionally Two Nights-Stay in San Francisco at the Marriott Airport San Francisco. Airfare for Two included. Donated by Trinchero Winery and Airfare Courtesy of The Miner Corporation 3……….Vacation on the Beach Manzanillo Villa for 8. One-week stay in a 4-Bedroom/4-Bath villa located on a cliffside overlooking the Pacific Ocean. Swimming pool. Cook/Housekeeper for hire. Santiago Country Club Membership. Fishing options. -

The Economics of Sports

Upjohn Press Upjohn Research home page 1-1-2000 The Economics of Sports William S. Kern Western Michigan University Follow this and additional works at: https://research.upjohn.org/up_press Part of the Economics Commons, and the Sports Management Commons Citation Kern, William S., ed. 2000. The Economics of Sports. Kalamazoo, MI: W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research. https://doi.org/10.17848/9780880993968 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 4.0 License. This title is brought to you by the Upjohn Institute. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Economics of Sports William S. Kern Editor 2000 W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research Kalamazoo, Michigan 49007 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data The economics of sports / William S. Kern, editor. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0–88099–210–7 (cloth : alk. paper) — ISBN 0–88099–209–3 (paper : alk. paper) 1. Professional sports—Economic aspects—United States. I. Kern, William S., 1952– II. W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research. GV583 .E36 2000 338.4'3796044'0973—dc21 00-040871 Copyright © 2000 W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research 300 S. Westnedge Avenue Kalamazoo, Michigan 49007–4686 The facts presented in this study and the observations and viewpoints expressed are the sole responsibility of the authors. They do not necessarily represent positions of the W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research. Cover design by J.R. Underhill. Index prepared by Nancy Humphreys. Printed in the United States of America. CONTENTS Acknowledgments v Introduction 1 William S. -

1 in the United States District Court for the District Of

CASE 0:18-cv-02140 Document 1 Filed 07/25/18 Page 1 of 14 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF MINNESOTA THIRD DIVISION D.M., a minor, by BAO XIONG, the mother, ) legal guardian, and next friend of D.M.; and ) Z.G., a minor, by JOEL GREENWALD, the ) JURY TRIAL DEMANDED father, legal guardian, and next friend of Z.G., ) ) Plaintiffs, ) v. ) Case No. _______________ ) MINNESOTA STATE HIGH SCHOOL ) LEAGUE; DAVID SWANBERG in his ) COMPLAINT FOR official capacity as President of the Board of ) DECLARATORY AND Directors for the MINNESOTA STATE ) INJUNCTIVE RELIEF HIGH SCHOOL LEAGUE; ERICH ) MARTENS in his official capacity as ) Executive Director of the MINNESOTA ) STATE HIGH SCHOOL LEAGUE; ) CRAIG PERRY in his official capacity as an ) Associate Director of the MINNESOTA ) STATE HIGH SCHOOL LEAGUE; and ) BOB MADISON in his official capacity as an ) Associate Director of the MINNESOTA ) STATE HIGH SCHOOL LEAGUE, ) ) Defendants. ) INTRODUCTION 1. D.M. and Z.G. (Plaintiffs) are rising juniors at two different Twin Cities-area high schools. They are not very much alike. D.M. is the soft-spoken son of first-generation Hmong immigrants. Z.G. is the outgoing son of a middle-class Minnesota family. But both boys love to dance. D.M found dance over a year ago when a friend took him to a jazz class. He took to it immediately. Dance provides D.M. with a sense of pride, a feeling of belonging, and self-esteem. Z.G., in contrast, first began dancing in the fifth grade. He loves the 1 CASE 0:18-cv-02140 Document 1 Filed 07/25/18 Page 2 of 14 combination of performance art and technical skill that comes with dancing competitively. -

Firm-Timeline 1989-2009.Pdf

February 28, 1991 June 1, 1990 January 15, 1990 HOW MCGRANN SHEA CARNIVAL STRAUGHN & LAMB BEGAN The Firm adds the Hennepin Regional Park District (Now Three Rivers January 1992 Hilton Convention Center Hotel. A month-long closing McGrann Shea is featured in the Star Tribune Metro Section in an Suburban Park District) as a client. The firm performed significant conducted in Chicago for the development phase and work for the District in securing the land and obtaining the funding for The Metrodome hosts Super Bowl XXVI. article entitled “Back in business/Dissident lawyers regroup.” The financing of the Hilton Convention Center Hotel is Bill McGrann, Andy Shea, Doug Carnival, Doug Franzen, Kathleen Lamb resigned from the first public park on Lake Minnetonka. The firm has served as bond In the span of October 1991 – March article highlights the departure of the lawyers from O’Connor & successfully concluded. The firm completed significant December 14, 1994 O’Connor & Hannan on the morning of Thursday December 14, 1989 due to O’Connor & counsel for the District for issuance of over $100 million of tax-exempt 1992, the Metrodome hosts the World Hannan. The photo accompanying the article includes: Bill legal work on this 800-room downtown hotel and Hannan’s representation of the government of El Salvador headed by President Alfredo McGrann, Andy Shea, Doug Franzen, Doug Carnival, Bob bonds for development of regional parks and bike trails. The Three Series, the Super Bowl and the NCAA McGrann Shea celebrated its fifth underground parking ramp as counsel to the Minneapolis Men’s Basketball Final Four. -

Events Funds Cast Shadows Over Combs' War Chest

High-Octane Moola: April 18, 2013 Events Funds Cast Shadows Over Combs’ War Chest Comptroller Nets $421,360 from Donors Tied to $57 Million in State Funding. F1, Beer Distributors and Dallas Cowboys Champion Susan Combs. ontributors tied to $57 million in grants to a slew of trade associations and sports entities from the state’s Events Trust Funds gave to hold events in Texas. The biggest paybacks C $421,360 to funds overseer Susan Combs for Combs’ political coffers have come from since the 2006 cycle, when she won her first MillerCoors distributors and the Circuit of the Comptroller race.1 Comptroller Combs has Americas, which hosts its first motorcycle grand awarded more than $222 million in state funds prix in Austin this weekend. Combs Contributions Associated With Events-Fund Awards Combs State Total Grants Top Associated ‘05 - ‘13 Events-Fund Awards Awarded Combs Contributor $129,511 MillerCoors Annual Distributor Conference $423,129 Wholesale Beer Distributors of TX $116,041 Formula 1 US Grand Prix/Moto GP COTA $26,987,753 BJ ‘Red’ McCombs $48,500 National Cattlemen's Beef Assn. $723,234 TX & SW Cattle Raisers Assn. $45,000 American Bankers Assn. $181,072 TX Bankers Assn. $30,000 Credit Union National Assn. $166,946 TX Credit Union League $23,481 American Quarter Horse Assn. $112,052 Chickasaw Nation* $11,577 NFL Super Bowl/Cowboys Classic Football $27,072,467 Cowboys owner Jerral W. Jones $6,500 Intern’l Veterinary Emerg./Critical Care Symp. $162,406 TX Veterinary Medical Assn. $4,500 Associated Builders & Contractors $159,330 Assoc. -

The Clear Picture on Clear Channel Communications, Inc.: a Corporate Profile

Cornell University ILR School DigitalCommons@ILR Articles and Chapters ILR Collection 1-28-2004 The Clear Picture on Clear Channel Communications, Inc.: A Corporate Profile Maria C. Figueroa Cornell University, [email protected] Damone Richardson Cornell University, [email protected] Pam Whitefield Cornell University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.ilr.cornell.edu/articles Part of the Advertising and Promotion Management Commons, Arts Management Commons, and the Unions Commons Thank you for downloading an article from DigitalCommons@ILR. Support this valuable resource today! This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the ILR Collection at DigitalCommons@ILR. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles and Chapters by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@ILR. For more information, please contact [email protected]. If you have a disability and are having trouble accessing information on this website or need materials in an alternate format, contact [email protected] for assistance. The Clear Picture on Clear Channel Communications, Inc.: A Corporate Profile Abstract [Excerpt] This research was commissioned by the American Federation of Labor-Congress of Industrial Organizations (AFL-CIO) with the expressed purpose of assisting the organization and its affiliate unions – which represent some 500,000 media and related workers – in understanding, more fully, the changes taking place in the arts and entertainment industry. Specifically, this report examines the impact that Clear Channel Communications, with its dominant positions in radio, live entertainment and outdoor advertising, has had on the industry in general, and workers in particular. Keywords AFL-CIO, media, worker, arts, entertainment industry, advertising, organization, union, marketplace, deregulation, federal regulators Disciplines Advertising and Promotion Management | Arts Management | Unions Comments Suggested Citation Figueroa, M. -

April Acquiring a Piece of Pottery at the Kidsview Seminars

Vol. 36 No. 2 NEWSLETTER A p r i l 2 0 1 1 Red Wing Meetsz Baseball Pages 6-7 z MidWinter Jaw-Droppers Page 5 RWCS CONTACTS RWCS BUSINESS OFFICE In PO Box 50 • 2000 Old West Main St. • Suite 300 Pottery Place Mall • Red Wing, MN 55066-0050 651-388-4004 or 800-977-7927 • Fax: 651-388-4042 This EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR: STACY WEGNER [email protected] ADMINISTRATIVE ASSISTANT: VACANT Issue............. [email protected] Web site: WWW.RedwINGCOLLECTORS.ORG BOARD OF DIRECTORS Page 3 NEWS BRIEFS, ABOUT THE COVER PRESIDENT: DAN DEPASQUALE age LUB EWS IG OUndaTION USEUM EWS 2717 Driftwood Dr. • Niagara Falls, NY 14304-4584 P 4 C N , B RWCS F M N 716-216-4194 • [email protected] Page 5 MIDWINTER Jaw-DROPPERS VICE PRESIDENT: ANN TUCKER Page 6 WIN TWINS: RED WING’S MINNESOTA TWINS POTTERY 1121 Somonauk • Sycamore, IL 60178 Page 8 MIDWINTER PHOTOS 815-751-5056 • [email protected] Page 10 CHAPTER NEWS, KIDSVIEW UPdaTES SECRETARY: JOHN SAGAT 7241 Emerson Ave. So. • Richfield, MN 55423-3067 Page 11 RWCS FINANCIAL REVIEW 612-861-0066 • [email protected] Page 12 AN UPdaTE ON FAKE ADVERTISING STOnewaRE TREASURER: MARK COLLINS Page 13 BewaRE OF REPRO ALBANY SLIP SCRATCHED MINI JUGS 4724 N 112th Circle • Omaha, NE 68164-2119 Page 14 CLASSIFIEDS 605-351-1700 • [email protected] Page 16 MONMOUTH EVENT, EXPERIMENTAL CHROMOLINE HISTORIAN: STEVE BROWN 2102 Hunter Ridge Ct. • Manitowoc, WI 54220 920-684-4600 • [email protected] MEMBERSHIP REPRESENTATIVE AT LARGE: RUSSA ROBINSON 1970 Bowman Rd. • Stockton, CA 95206 A primary membership in the Red Wing Collectors Society is 209-463-5179 • [email protected] $25 annually and an associate membership is $10. -

An Analysis of the American Outdoor Sport Facility: Developing an Ideal Type on the Evolution of Professional Baseball and Football Structures

AN ANALYSIS OF THE AMERICAN OUTDOOR SPORT FACILITY: DEVELOPING AN IDEAL TYPE ON THE EVOLUTION OF PROFESSIONAL BASEBALL AND FOOTBALL STRUCTURES DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Chad S. Seifried, B.S., M.Ed. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2005 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Donna Pastore, Advisor Professor Melvin Adelman _________________________________ Professor Janet Fink Advisor College of Education Copyright by Chad Seifried 2005 ABSTRACT The purpose of this study is to analyze the physical layout of the American baseball and football professional sport facility from 1850 to present and design an ideal-type appropriate for its evolution. Specifically, this study attempts to establish a logical expansion and adaptation of Bale’s Four-Stage Ideal-type on the Evolution of the Modern English Soccer Stadium appropriate for the history of professional baseball and football and that predicts future changes in American sport facilities. In essence, it is the author’s intention to provide a more coherent and comprehensive account of the evolving professional baseball and football sport facility and where it appears to be headed. This investigation concludes eight stages exist concerning the evolution of the professional baseball and football sport facility. Stages one through four primarily appeared before the beginning of the 20th century and existed as temporary structures which were small and cheaply built. Stages five and six materialize as the first permanent professional baseball and football facilities. Stage seven surfaces as a multi-purpose facility which attempted to accommodate both professional football and baseball equally. -

Keenan Allen, Mike Williams and Austin Ekeler, and Will Also Have Newly-Signed 6 Sun ., Oct

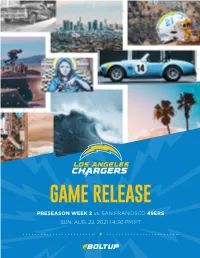

GAME RELEASE PRESEASON WEEK 2 vs. SAN FRANCISCO 49ERS SUN. AUG. 22, 2021 | 4:30 PM PT bolts build under brandon staley 20212020 chargers schedule The Los Angeles Chargers take on the San Francisco 49ers for the 49th time ever PRESEASON (1-0) in the preseason, kicking off at 4:30 p m. PT from SoFi Stadium . Spero Dedes, Dan Wk Date Opponent TV Time*/Res. Fouts and LaDainian Tomlinson have the call on KCBS while Matt “Money” Smith, 1 Sat ., Aug . 14 at L .A . Rams KCBS W, 13-6 Daniel Jeremiah and Shannon Farren will broadcast on the Chargers Radio Network 2 Sun ., Aug . 22 SAN FRANCISCO KCBS 4:30 p .m . airwaves on ALT FM-98 7. Adrian Garcia-Marquez and Francisco Pinto will present the game in Spanish simulcast on Estrella TV and Que Buena FM 105 .5/94 .3 . 3 Sat ., Aug . 28 at Seattle KCBS 7:00 p .m . REGULAR SEASON (0-0) The Bolts unveiled a new logo and uniforms in early 2020, and now will be unveiling a revamped team under new head coach, Brandon Staley . Staley, who served as the Wk Date Opponent TV Time*/Res. defensive coordinator for the Rams in 2020, will begin his first year as a head coach 1 Sun ., Sept . 12 at Washington CBS 10:00 a .m . by playing against his former team in the first game of the preseason . 2 Sun ., Sept . 19 DALLAS CBS 1:25 p .m . 3 Sun ., Sept . 26 at Kansas City CBS 10:00 a .m . Reigning Offensive Rookie of the YearJustin Herbert looks to build off his 2020 season, 4 Mon ., Oct . -

ORANGE SLICES Greg Robinson Third 6-23 33-43 6-23 Seventh 2-14 Dick Macpherson Chris Gedney ‘93 33-43 12-30 Brian Higgins ‘04 and Former Orange All- Seventh Third

2007 SYRACUSE FOOTBALL S SYRACUSE (1-5 overall, 1-1 BIG EAST) vs. RUTGERS (3-2 overall, 0-1 BIG EAST) • October 13, 2007 (12:00 p.m. • ESPN Regional) • Carrier Dome • Syracuse, N.Y. • ORANGE SLICES ORANGE AND RUTGERS CLASH IN BIG EAST BATTLE ORANGE PRIDE The SU football team will host Rutgers at 12:00 p.m. on Saturday, Oct. 13 at the Carrier Dome. On the Air For the Orange, its the third straight conference game against a team that entered 2007 ranked in the national polls. SU is 1-1 in the BIG EAST, defeating then-#18/19 Louisville on Television the road, 38-35, on Sept. 22 and losing at home to the #13/12 Mountaineers on Oct. 6. Syracuse’s game versus Rutgers will be televised by ESPN Regional. Dave Sims, John The Orange owns a dominating 28-8-1 lead in the all-time series, including a 14-4-1 record in Congemi and Sarah Kustok will have the call. games played in Syracuse and will look to snap a two-game losing streak to RU. Casey Carter is the producer. Both Syracuse and are looking to get back on the winning track after losses in each of the last two weeks. Syracuse is coming off losses at Miami (OH) and at home to #13/12 West Radio Virginia. Rutgers lost a non-league encounter with Maryland two weeks ago and lost at home Syracuse ISP Sports Network to Cincinnati in its BIG EAST opener on Oct. 6. The flagship station for the Syracuse ISP Saturday’s game will televised live on ESPN Regional. -

Sports Golf » 5 Sidelines » 6 SATURDAY, JUNE 20, 2020 • the PRESS DEMOCRAT • SECTION C Weather » 6

Inside Baseball » 2 Sports Golf » 5 Sidelines » 6 SATURDAY, JUNE 20, 2020 • THE PRESS DEMOCRAT • SECTION C Weather » 6 CORONAVIRUS SRJC » FOOTBALL Players across A teammate gone leagues Rashaun Harris, a defensive infected back on the Santa Rosa Junior College Bear Cubs football team, was killed 49ers player, several in in a drive-by shooting baseball, hockey tested while visiting his family in Sacramento in May. His positive this week older sister believes it was a case of mistaken identity. In PRESS DEMOCRAT NEWS SERVICES these photos shared by his family and SRJC coach Len- ny Wagner, Harris is seen as PHILADELPHIA — The San he poses with a teammate, Francisco Giants shuttered as a young teen, in his SRJC their spring complex due to uniform and at the beach. fears over exposure to the coro- He was 23. navirus and at least two other teams did the same Friday af- ter players and staff tested pos- itive, raising the possibility the ongoing pandemic could scuttle all attempts at a Major League Baseball season. Elsewhere, an unidentified San Francisco 49ers player reportedly tested positive for COVID-19 after an informal workout with teammates in Tennessee. The NFL Network reported PHOTOS Friday that one player who took COURTESY OF DAJONNAE HARRIS part in the workouts this week AND LENNY WAGNER in Nashville has tested positive. All the players who were there will now get tested to see if there is any spread. The Giants’ facility was shut after one person who had been to the site and one family member exhibited symptoms Thursday.